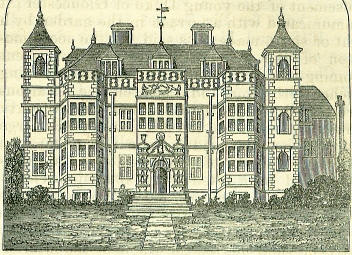

23rd MarchBorn: Pierre Simon Laplace, French savant, author of Mècanique Cèleste, 1749, Beaumont-en-Ange; William Smith, 'The Father of English Geology,' 1769. Died: Peter the Cruel, king of Castile, 1369; Pope Julius III, 1556; Justus Lipsius, eminent historical writer, 1606, Louvain; Paul, Emperor of Russia, assassinated, 1801, St. Petersburg; Thomas Holcroft, miscellaneous writer, 1809; Duchess of Brunswick, sister of George III, 1813; Augustus Frederick Kotzebue, German dramatist, 1819, assassinated at Mannheim; Carl Maria von Weber, German musical composer, 1829, London; Archdeacon Nares, philologist, 1829. Feast Day: St. Victorian, proconsul of Carthage, and others, martyrs, 484. St. Edelwald, of England, 699. St. Alphonsus Turibius, Archbishop of Lima, 1606. WEDNESDAY IN HOLY WEEK IN LENTOn this occasion the only ceremony that attracts attention is the singing of the first Miserere in the Sistine Chapel. This commences at half-past four in the afternoon. The crowding is usually very great. The service, which is sometimes called Tenebrae, from the darkness of the night in which it was at one time celebrated, is repeated on the two following days in the Sistine Chapel, and singing not greatly different takes place also in St. Peter's. The whole office of Tenebrae is a highly-finished musical composition, performed by the organ and the voices of one of the finest choirs in the world. Some parts are of exquisite beauty and tenderness. We give the following account of the composition from a work quoted below.: In no other place has this celebrated music ever succeeded. Baini, the director of the pontifical choir, in a note to his Life of Palestrina, observes that on Holy Wednesday, 1519 (pontificate of Leo X), the singers chanted the Miserere in a new and unaccustomed manner, alternately singing the verses in symphony. This seems to be the origin of the far-famed Miserere. Various authors, whom Baini enumerates, afterwards composed Miserere; but the celebrated composition of Gregorio Allegri, a Roman, who entered the papal college of singers in 1629, was the most successful, and was for some time sung on all the days of Tenebrae. Ultimately, the various compositions were eclipsed by the Miserere composed by Bai; but since 1821 the compositions of Baini, Bai, and Allegri are sung on the three successive days, the two latter sometimes blended together. The first verse is sung in harmony, the second in plain chant, and so successively till the last verse. At the office of the Miserere, a ceremony takes place that may be described from the same authority: 'A triangular candlestick, upon which are fifteen candles, corresponding to the number of psalms recited, is placed at the epistle side of the altar. After each psalm one of the candles is extinguished by a master of the ceremonies, and after the Benedictus the candle on the top is alone not extinguished, but it is removed and concealed behind the altar, and brought out at the end of the service; while that canticle is sung the six candles on the altar also are extinguished, as well as those above the rails. The custom of concealing the last and most elevated candle, and of bringing it forward burning at the end of the service, is in allusion to the death and resurrection of Christ, whose light is represented by burning tapers. In the same manner, the other candles extinguished one after another, may represent the prophets successively put to death before their divine Lord.' PEDRO THE CRUELPedro I, King of Castile, styled the Cruel has been stigmatised as unnatural, cruel, an infidel, and a fratricide; but Pedro's fratricide consisted in executing an illegitimate brother who was about to assassinate him, and his infidelity appears chiefly to have been hatred of the monks. The latter, in their turn, hated him, and as their pens were more lasting than his sceptre, Pedro's name has descended to posterity blackened by the accusation of almost every crime which man could commit. Don Pedro was born in 1334, and died by the dagger of his illegitimate brother Enrique (who usurped his throne) at Montièl, on the 23rd of March. 1369, aged thirty-five. His two surviving daughters became the wives of John of Gaunt and Edmund of Langley, sons of Edward III of England. This Prince is one of the first modern kings who possessed the accomplishment of writing. Our Henry I ('Beauclerc') could not write, and signed with a mark, as any one may see who will take the trouble to consult Cott. MS. Vesp. F. iii. (British Museum). ENGLAND LAID UNDER INTERDICTOn the 23rd of March 1208, England underwent the full vengeance of the papal wrath. King John had occupied the throne during nearly nine years, and had contrived to lose his continental territories, and to incur the hatred of his subjects; and he now quarrelled with the Church, --then a very formidable power. The ground of dispute was the appointment of an Archbishop of Canterbury; and as the ecclesiastics of Canterbury espoused the papal choice, John treated them with a degree of brutality which could not fail to provoke the utmost indignation of the Court of Rome. Innocent III, who at this time occupied the papal chair, expostulated with the king of England, and demanded redress, following up these demands with threats of laying an interdict upon the kingdom, and excommunicating the king. When these threats were announced to John, 'the king,' to use the words of the contemporary historian, Roger de Wendover, 'became nearly mad with rage, and broke forth in words of blasphemy against the Pope and his cardinals, swearing by God's teeth that, if they or any other priests soever presumptuously dared to lay his dominions under an interdict, he would banish all the English clergy, and confiscate all the property of the church;' adding that, if he found any of the Pope's clerks in England, he would send them home to Rome with their eyes torn out and their noses split, 'that they might be known there from other people.' Accordingly, on Easter Monday, 1208, which that year fell on the 23rd of March, the three bishops of London, Ely, and Winchester, as the Pope's legates, laid a general interdict on the whole of England, by which all the churches were closed, and all religious service was discontinued, with the exception of confession, the administration of the viaticum on the point of death, and the baptism of children. Marriages could no longer be celebrated, and the bodies of the dead 'were carried out of cities and towns, and buried in roads and ditches, without prayers or the attendance of priests.' The king retaliated by carrying out his threat of confiscation; he seized all the church property, giving the ecclesiastical proprietors only a scanty allowance of food and clothing. 'The corn of the clergy was every-where locked up,' says the contemporary writer, 'and distrained for the benefit of the revenue; the concubines of the priests and clerks were taken by the king's servants, and compelled to ransom themselves at a great expense; monks and other persons ordained, of any kind, when found travelling on the roads, were dragged from their horses, robbed, and basely ill-treated by the king's satellites, and no one would do them justice. About that time the sergeants of a certain sheriff on the borders of Wales came to the king, bringing in their custody, with his hands tied behind him, a robber who had robbed and murdered a priest on the high road; and on their asking the king what it was his pleasure should be done to a robber in such a case, the king immediately replied, 'He has only slain one of my enemies release him, and let him go.' 'In such a state of things, it is not to be wondered at if the higher ecclesiastics fled to the Continent, and as many of the others as could make their escape followed their example. This gloomy period, which lasted until the taking off the interdict in 1214, upwards of six years, was long remembered in the traditions of the peasantry. We have heard a rather curious legend, on tradition, connected with this event. Many of our readers will have noticed the frequent occurrence, on old common lands, and even on the sides of wild mountains and moorlands, of the traces of furrows, from the process of ploughing the land at some very remote period. To explain these, it is pretended that King John's subjects found an ingenious method of evading one part of the interdict, by which all the cultivated land in the kingdom. was put under a curse. People were so superstitious that they believed that the land which lay under this curse would be incapable of producing crops, but they considered that the terms of the interdict applied only to land in cultivation at the time when it was proclaimed, and not to any which began to be cultivated afterwards; and to evade its effect, they left uncultivated the land which had been previously cultivated, and ploughed the commons and other uncultivated lands: and that the furrows we have alluded to are the remains of this temporary cultivation. It is probable that this interpretation is a very erroneous one; and it is now the belief of antiquaries that most of these very ancient furrow-traces, which have been remarked especially over the Northumbrian hills, are the remains of the agriculture of the Romans, who obtained immense quantities of corn from Britain, and appear to have cultivated great extents of land which were left entirely waste during the middle ages. Our mediaeval forefathers frequently shewed great ingenuity in evading the ecclesiastical lairs and censures. We have read in an old record, the reference to which we have mislaid, of a wealthy knight, who, for his offences, was struck with the excommunication of the Church, and, as he was obstinate in his contumacy, died under the sentence. According to the universal belief, a man dying under such circumstances had no other prospect but everlasting damnation. But our knight had remarked that the terms of the sentence were that he would be damned whether buried within the church or without the church, and he gave orders to make a hole in the exterior wall of the building, and to bury his body there, believing that, as it was thus neither within the church nor without the church, he would escape the effects of the excommunication. Curiously enough, one or two examples have been met with of sepulchral interments within church walls, but it may perhaps be doubted if they admit of this explanation. CAMPDEN HOUSE, KENSINGTONOn the morning of Sunday, March 23, 1862, at about four o'clock, the mansion known as Campden House, built upon the high ground of Kensington just two centuries and a half ago, was almost entirely destroyed by fire. It was one of the few old mansions in the environs of the metropolis which time has spared to our day; it belonged to a more picturesque age of architecture than the present; and though yielding in extent and beauty to its more noble neighbour, Holland House, built within five years of the same date, and which in general style it resembled, was still a very interesting fabric. It was built for Sir Baptist Hicks, about the year 1612; and his arms, with that date, and those of his son-in-law, Edward Lord Noel, and Sir Charles Morison, were emblazoned upon a large bay-window of the house. In the same year (1612), he built the Sessions House in the broad part of St. John Street, Clerkenwell; it was named after him, Hicks's Hall, a name more familiar than Campden House, from the former being inscribed upon scores of milestones in the suburbs of London, the distances being measured 'from Hicks's Hall.' This Hall lasted about a century and a half, when it fell into a ruinous condition, and a new Hall was built on Clerkenwell Green, and thither was removed a handsomely carved wood mantelpiece from the old Hall, together with a portrait of Sir Baptist Hicks, painter unknown, and stated by Sir Bernard Burke to have never been engraved: it hung in the dining-room at the Sessions House. Baptist Hicks was the youngest son of a wealthy silk-mercer, at the sign of the White Bear, at Soper Lane end, in Cheapside. He was brought up to his father's business, in which he amassed a considerable fortune. In 1603, he was knighted by James I, which occasioned a contest between him and the alderman, respecting precedence; and in 1611, being elected alderman of Broad Street ward, he was discharged, on paying a fine of £500, at the express desire of the King. Strype tells us that Sir Baptist was one of the first citizens that, after knighthood, kept their shops; but being charged with it by some of the aldermen, he gave this answer: That his servants kept the shop, though he had a regard to the special credit thereof; and that he did not live altogether upon interest, as most of the alderman knights did, laying aside their trade after knighthood; and that, had two of his servants kept their promise and articles concluded between them and him, he had been free of his shop two years past; and did then but seek a fit opportunity to leave the same. This was in the year 1607. Sir Baptist was created a baronet 1st July 1620; and was further advanced to the peerage as Baron Hicks, of Ilmington, in the county of Warwick; and Viscount Campden, in Gloucestershire, 5th May 1628. He died at his house in the Old Jewry, 18th October 1629, and was buried at Campden. He was a distinguished member of the Mercers' Company, to which his widow made a liberal bequest, one object of which was to assist young freemen beginning business as shopkeepers, with the gratuitous loan of £1000. Lady Campden was also a benefactress to the parish of Kensington. The Campden House estate was purchased by Sir Baptist Hicks from Sir Walter Cope, or, according to a tradition in the parish, was won of him at some game of chance. Bowack, in his Antiquities of Middlesex, describes it as 'a very noble pile, and finished with all the art the architects of that time were masters of; the situation being upon a hill, makes it extreme healthful and pleasant.' Sir Baptist Hicks had two daughters, co-heiresses, who are reputed to have had £100,000 each for their fortune: the oldest, Juliana, married Lord Noel, to whom the title devolved at the first Viscount Campden's decease; Mary, the youngest daughter, married Sir Charles Morison, of Cashiobury, Herts. Baptist, the third Lord Campden, who was a zealous royalist, lost much property during the Civil Wars, but was permitted to keep his estates on paying the sum of £9000 as a composition, and making a settlement of £150 per annum on the Commonwealth Ministry. He resided chiefly at Campden House during the Protectorate: the Committee for Sequestrations held their meetings here. At the Restoration, the King honoured Lord Campden with particular notice; and we read in the Mereurius Politicus, that on June 8, 1666, His Majesty was pleased to sup with Lord Campden at Kensington.' In 1662, an Act was passed for settling Campden House upon this nobleman and his heirs forever; and in 1667, his son-in-law, Montague Bertie, Earl of Lindsey, who so nobly distinguished himself by his filial piety at the battle of Edge Hill, and who was wounded at Naseby, died in this house. In 1691, Anne, Princess of Denmark, hired Campden House from the Noel family, and resided there for about five years with her son, William Duke of Gloucester, then heir-presumptive to the throne. The adjoining house is said to have been built at this time for the accommodation of her Royal Highness's household: it was named Little Campden House, and was for some time the residence of William Pitt; it had an outer arcaded gallery, and was subsequently called The Elms, and tenanted by Mr. Egg, the painter: it was greatly injured by the late fire. At Campden House, the young Duke's amusements were chiefly of a military cast; and at a very early age he formed a regiment of boys, chiefly from Kensington, who were on constant duty here. He was placed under the care of the Earl of Marlborough and of Bishop Burnet. When King William gave him into the hands of the former, 'Teach him to be what you are,' said the King, 'and my nephew cannot want accomplishments.' Bishop Burnet, who had super-intended his education for ten years, describes him as an amiable and accomplished prince, and in describing his education, says, 'The last thing I explained to him was the Gothic constitution, and the beneficiary and feudal laws: I talked of these things, at different times, near three hours a day. The King ordered five of his chief ministers to come once a quarter, and examine the progress he had made.' They were astonished at his proficiency. He was, however, of weak constitution; 'but,' says the Bishop, 'we hoped the dangerous time was over. His birthday was on the 24th of July 1700, and he was then eleven years old: he complained the next day, but we imputed that to the fatigue of a birthday, so that he was too much neglected; the day after, he grew much worse, and it proved to be a malignant fever. He died (at Windsor) on the fourth day of his illness: he was the only remaining child of seventeen that the Princess had borne.' Burnet adds, 'His death gave great alarm to the whole nation. The Jacobites grew insolent upon it, and said, now the chief difficulty was removed out of the way of the Prince of Wales's succession.' Mr. Shippen, who then resided at Holland House, wrote the following lines upon the young Prince's death: So, by the course of the revolving spheres, Whene'er a new discovered star appears, Astronomers, with pleasure and amaze, Upon the infant luminary gaze. They find their heaven's enlarged, and wait from thence Some blest, some more than common influence; But suddenly, alas! the fleeting light, Retiring, leaves their hopes involved in endless night. In 1704, Campden House was in the occupation of the Dowager Countess of Burlington, and of her son the architect Earl, then in his ninth year. In the latter part of Queen Anne's reign, Campden House was sold to Nicholas Lechmere, an eminent lawyer, who became Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and Attorney-General. In 1721, he was created a peer, and Swift's ballad of Duke upon Duke, in which the following lines occur, had its origin in a quarrel between his lordship, who then occupied this mansion, and Sir John Guise: Back in the dark, by Brompton Park, He turned up through the Gore, So slunk to Campden House so high, All in his coach and four. The Duke in wrath call'd for his steeds, And fiercely drove them on; Lord! Lord! how rattled then thy stones, O kingly Kensington! Meanwhile, Duke Guise did fret and fume, A sight it was to see, Benumbed beneath the evening dew, Under the greenwood tree. The original approach to Campden House from the town of Kensington was through an avenue of elms, which extended nearly to the High-street and great western road, through the grounds subsequently the cemetery. About the year 1798, the land in front of the house was planted with trees, which nearly cut off the view from the town; and at the same time a new road was made to the east, and planted with a shrubbery. About this time, Lyons describes a caper-tree, which had flourished in the garden of Campden House for more than a century. Miller speaks of it in the first edition of his Gardener's Dictionary; it was sheltered from the north, having a south-east aspect, and though not within the reach of any artificial heat, it produced fruit every year.  The olden celebrity of Campden House may be said to have ceased a century since; for Faulkner, in his History and Antiquities of Kensington, 1820, states it to have then been occupied more than sixty years as a boarding-school for ladies. He describes the piers of the old gateway as then surmounted by two finely sculptured dogs, the supporters of the Campden arms, which were placed there when the southern avenue was removed in the year 1798. The mansion was built of brick, with stone finishings; and a print of the year 1793 shews the principal or southern front, of three stories, to have then consisted of three bays, flanked by two square turrets, surmounted with cupolas; the central bay having an enriched Jacobean entrance porch, with the Campden arms sculptured above the first-floor bay-windows; a pierced parapet above; and dormer windows in the roof. As usual with old mansions, as the decorated portions decay, they are not replaced; and Faulkner's view of this front, in 1820, shews the turrets without the cupola roofs; the main roof appears flat, and the ornamental porch has given way to a pair of plain columns supporting the central bay-window. He describes this front as having lost most of its original ornaments, and being then covered with stucco. His view also shows the eastern end, with its bays and gables, its stacks of chimneys in the form of square towers, and the brickwork panelled according to the original design. The north or garden front was, at the same period, more undermined than the south front; and westward the mansion adjoined Little Campden House. Faulkner described-two-and-forty years since, be it remembered-the entrance-hall lined with oak panelling, and having an archway leading to the grand staircase; on the right was a large parlour, modernised; and on the west were the domestic offices. The great dining-room, in which Charles II supped with Lord Campden, was richly carved in oak; and the ceiling was stuccoed, and ornamented with the arms of the Campden family. But the glory of this room was the tabernacle oak mantelpiece, consisting of six Corinthian columns, supporting a pediment; the intercolumniations being filled with grotesque devices, and the whole supported by two caryatidal figures, finely carved. The state apartments on the first floor consisted of three large rooms facing the south; that on the east, 'Queen Anne's bed-chamber,' had an enriched plaster ceiling, with pendants, and the walls were hung with red damask tapestry, in imitation of foliage. The central apartment originally had its large bay-window filled with painted glass, shewing the arms of Sir Baptist Hicks, Lord Noel, and Sir Charles Morison; and the date of the erection of the mansion, 1612. The eastern wing, on the first floor, contained 'the globe-room,' which Faulkner thought to have been originally a chapel; but we rather think it had been the theatre for puppets, fitted up for the amusement of the young Duke of Gloucester; it communicated with a terrace in the garden by a flight of steps, made, it is said, for the accommodation of the Princess Anne. The apartment adjoining that last named had its plaster ceiling enriched with arms, and a mantelpiece of various marbles. Such was the Campden House of sixty years since. Within the last dozen years, large sums had been expended upon the restoration and embellishment of the interior: a spacious theatre had been fitted up for amateur performances, and the furniture and enrichments were in sumptuous taste, if not in style accordant with the period of the mansion; but, whatever may have been their merits, the whole of the interior, its fittings and furniture, were destroyed in the conflagration of March 23rd; and before the Londoners had risen from their beds that Sunday morning, all that remained of Campden House, or 'Queen Anne's Palace,' as it was called by the people of Kensington, were its blackened and windowless walls. As the abode of the ennobled merchant of the reign of James I; where Charles II feasted with his loyal chamberlain; and as the residence of the Princess, afterwards Queen Anne, and the nursing home of the heir to the British throne, Campden House is entitled to special record, and its disappearance to a passing note. SWALLOWING A PADLOCKMedical men see more strange things, perhaps, than any other persons. They are repeatedly called upon to grapple with difficulties, concerning which there is no definite line of treatment generally recognized; or to treat exceptional cases, in which the usual course of proceeding cannot with safety be adopted. If it were required to name the articles which a woman would not be likely to swallow, a brass padlock might certainly claim a place in the list; and we can well imagine that a surgeon would find his ingenuity taxed to grapple with such a case. An instance of this kind took place at Edinburgh in 1837; as recorded in the local journals, the particulars were as follows: On the 23rd of March, the surgeons at the Royal Infirmary were called upon to attend to a critical case. About the middle of February, a woman, while engaged in some pleasantry, put into her mouth a small brass padlock, about an inch and two-thirds in length, and rather more than an inch in breadth. To her consternation, it slipped down her throat. Fear of distressing her friends led her to conceal the fact. She took an emetic, but without effect; and for twenty-four hours she was in great pain, with a sensation of suffocation in the throat. She then got better, and for more than a month suffered but little pain. Renewed symptoms of inconvenience led her to apply to the Infirmary. One of the professors believed the story she told; others deemed it incredible; and nothing immediately was done. When, however, pain, vomiting, and a sense of suffocation returned, Dr. James Johnson, hospital-assistant to Professor Lizars, was called upon suddenly to attend to her. He saw that either the padlock must be extracted, or the woman would die. An instrument was devised for the purpose by Mr. Macleod, a surgical instrument maker; and, partly by the skill of the operator, partly by the ingenious formation of the instrument, the strange mouthful was extracted from the throat. The woman recovered. |