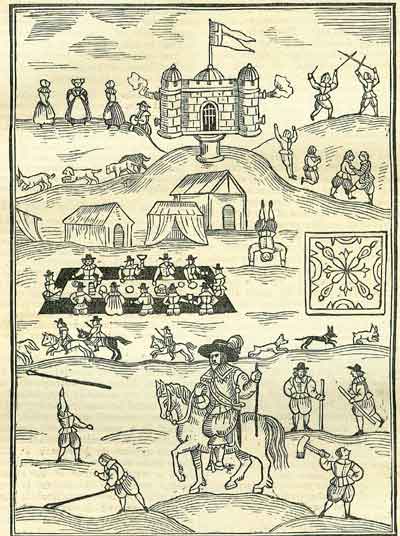

31st MayBorn: Dr. James Currie, miscellaneous writer, 1756, Kirkpatrick Fleming, Dumfriesshire; Friedrich Von Hardenberg, Prussian statesman, 1772; Ludwig Tieck, German poet, novelist, and dramatist, 1773. Died: Bishop Simon Patrick, 1707, Ely; William Baxter, editor of Latin classics, antiquary, 1723, buried at Islington; Philip Duke of Wharton, 1731, Terragone; Frederick William I of Prussia, 1740; Marshal Lannes, (Duc de Montebello), 1809; Joseph Grimaldi, comedian, 1837; Thomas Chalmers, D.D., 1847; Charlotte Bronte, novelist, 1855; Daniel Sharpe, F. R. S., geologist, 1856. Feast Day: St. Petronilla, 1st century; Saints Cantius and Cantianus, brothers, and Cantianilla, their sister, martyrs, 304. PHILIP DUKE OF WHARTONBrilliant almost beyond comparison was the prospect with which this erratic nobleman began his earthly career. His family, hereditary lords of Wharton Castle and large estates in Westmoreland, had acquired, by his grandfather's marriage with the heiress of the Goodwins, considerable property, including two other mansions, in the county of Buckingham. His father, Thomas, fifth Lord Wharton, was endowed with uncommon talent, and had greatly distinguished himself at court, in the senate, and in the country. Having proved himself a skilful politician, an able debater, and no less a zealous advocate of the people than supporter of the reigning sovereign, he had considerably advanced his family, both in dignity and influence. In addition to his hereditary title of Baron Wharton, he had been created Viscount Winchenden and Earl of Wharton in 1706; and in 1715, George I made him Earl of Rathfarnham and Marquis of Gatherlough in Ireland, and Marquis of Wharton and Malmesbury in England. He was also entrusted with several posts of honour and emolument. Thus, possessed of a large income, high in the favour of his sovereign, the envy or admiration of the nobility, and the idol of the people, he lived in princely splendour-chiefly at Wooburn, in Bucks, his favourite country-seat, on which he had expended £100,000 merely in ornamenting and improving it. With the view of qualifying Philip, his only surviving son, for the eminent position he had achieved for him, he had him educated at home under his own supervision. And the boy's early years were as full of promise as the fondest or most ambitious father could desire. Handsome and graceful in person, he was equally remarkable for the vigour and acuteness of his intellect. He learned with great facility ancient and modern languages, and, being naturally eloquent, and trained by his father in the art of oratory, he became a ready and effective speaker. When he was only about nine years old, Addison, who visited his father at Winchenden House, Bucks, was charmed and astonished at 'the little lad's' knowledge and intelligence; and Young, the author of the Night Thoughts, called him 'a truly prodigious genius.' But these flattering promises were soon marred by his early predilection for low and dissolute society; and his own habits speedily resembled those of his boon companions. His father, alarmed at his perilous situation, endeavoured to rescue him from the slough into which he was sinking; but his advice and efforts were only met by his son's increased deceit and alienation. When scarcely fifteen years old, he contracted a clandestine marriage with a lady greatly his inferior in family and station. When his father became acquainted with this, his last hope vanished. His ambitious spirit could not bear the blow, and he died within six weeks after the marriage. Hope still lingered with the fonder and deeper affections of his mother. But self-gratification was the ruling passion of her son; and, reckless of the feelings of others, he rushed deeper and deeper into vice and degradation. His mother's lingering hope was crushed, and she died broken-hearted within twelve months after his father. These self-caused bereavements, enough to have softened the heart of a common murderer, made no salutary impression on him. He rather seemed to hail them as welcome events, which opened for him the way to more licentious indulgence. For he now devoted himself unreservedly to a life of vicious and sottish pleasures; but, being still a minor, he was in some measure subject to the control of his guardians, who, puzzled what was best to do with such a character, decided on a very hazardous course. They engaged a Frenchman as his tutor or companion, and sent him to travel on the Continent, with a special injunction to remain some considerable time at Geneva, for the reformation of his moral and religious character. Proceeding first to Holland, he visited Hanover and other German courts, and was everywhere honourably received. Next proceeding to Geneva, he soon became thoroughly disgusted at the manners of the place, and, with contempt both for it and for the tutor who had taken him there, he suddenly quitted both. He left behind him a bear's cub, with a note to his tutor, stating that, being no longer able to submit to his treatment, he had committed to his care his young bear, which he thought would be a more suitable companion to him than himself-a piece of wit which might easily have been turned against himself. He had proceeded to Lyons, which he reached on the 13th of October 1716, and immediately sent from thence a fine horse as a present to the Pretender, who was then living at Avignon. On receiving this present the Pretender invited him to his court, and, on his arrival there, welcomed him with enthusiasm, and conferred on him the title of Duke of Northumberland. From Lyons he went to Paris, and presented himself to Mary D'Este, widow of the abdicated King James II. Lord Stair, the British ambassador at the French court, endeavoured to reclaim him by acts of courtesy and kindness, accompanied with some wholesome advice. The duke returned his civilities with politeness-his advice with levity. About the close of the year 1716, he returned to England, and soon after passed to Ireland; where he was allowed, though still a minor, to take his seat in parliament as Marquis of Catherlough. Despite his pledges to the Pretender, he now joined his adversaries, the king and government who debarred him from the throne. So able and important was his support, that the king, hoping to secure him on his side, conferred on him the title of Duke of Wharton. When he returned to England, he took his seat in the house as duke, and almost his first act was to oppose the government from whom he had received his new dignity. Shortly afterwards he professed to have changed his opinions, and told the ministerial leaders that it was his earnest desire to retrace his steps, and to give the king and his government all the support in his power. He was once more taken into the confidence of ministers. He attended all their private conferences; he acquainted himself with all their intentions; ascertained all their weak points; then, on the first important ministerial measure that occurred, he used all the information thus obtained to oppose the government, and revealed, with unblushing effrontery, the secrets with which they had entrusted him, and summoned all his powers of eloquence to overthrow the ministers into whose confidence he had so dishonourably insinuated himself. He made a most able and effective speech-damaging, indeed, to the minis-try, but still more damaging to his own character. His fickle and unprincipled conduct excited the contempt of all parties, each of whom he had in turn courted and betrayed. Lost to honour, overwhelmed with debt, and shunned by all respectable society, he abandoned himself to drunkenness and debauchery. 'He drank immoderately,' says Dr. King, 'and was very abusive and sometimes mischievous in his wine; so that he drew on himself frequent challenges, which he would never answer. On other accounts likewise, his character was become very prostitute.' So that, having lost his honour, he left his country and went to Spain. While at Madrid he was recalled by a writ of Privy Seal, which he treated with contempt, and openly avowed his adherence to the Pretender. By a decree in Chancery his estates were vested in the hands of trustees, who allowed him an income of £1200 a-year. In April 1726, his first wife died, and soon afterwards he professed the Roman Catholic faith, and married one of the maids of honour to the Queen of Spain. This lady, who is said to have been penniless, was the daughter of an Irish colonel in the service of the King of Spain, and appears only to have increased the duke's troubles and inconsistency; for shortly after his marriage he entered the same service, and fought against his own countrymen at the siege of Gibraltar. For this he was censured even by the Pretender, who advised him to return to England; but, contemptuous of advice from every quarter alike, he proceeded to Paris. Sir. Edward Keane, who was thou at Paris, thus speaks of him: The Duke of Wharton has not been sober, or scarce had a pipe out of his mouth, since he left St. Ildefonso . . . He declared himself to be the Pretender's prime minister, and Duke of Wharton and Northumberland. 'Hitherto,' added he, 'my master's interest has been managed by the Duke of Perth, and three or four other old women, who meet under the portal of St. Germains. He wanted a Whig, and a brisk one, too, to put them in a right train, and I am the man. You may look on me as Sir Philip Wharton, Knight of the Garter, running a race with Sir Robert Walpole, Knight of the Bath-running a course, and he shall be hard pressed, I assure you. He bought my family pictures, but they shall not be long in his possession; that account is still open; neither he nor King George shall be six months at ease, as long as I have the honour to serve in the employment I am now in.' He mentioned great things from Muscovy, and talked such. nonsense and contradictions, that it is neither worth my while to remember, nor yours to read them. I used him very cavalierement, upon which he was much affronted--sword and pistol next day. But before I slept, a gentleman was sent to desire that everything might be forgotten. What a pleasure must it have been to have killed a prime minister! From Paris the duke went to Rouen, and living there very extravagantly, he was obliged to quit it, leaving behind his horses and equipage. He returned to Paris, and finding his finances utterly exhausted, entered a monastery with the design of spending the remainder of his life in study and seclusion; but left it in two months, and, accompanied by the duchess and a single servant, proceeded to Spain. His erratic career was now near its close. His dissolute life had ruined his constitution, and in 1731 his health began rapidly to fail. He found temporary relief from a mineral water in Catalonia, and shortly afterwards relapsing into his former state of debility, he again set off on horseback to travel to the same springs; but ere he reached them, he fell from his horse in a fainting fit, near a small village, from whence he was carried by some Bernardine monks to a small convent near at hand. Here, after languishing for a few days, he died, at the age of thirty-two, without a friend to soothe his dying moments, without a servant to minister to his bodily sufferings or perform the last offices of nature. On the 1st of June 1731, the day after his decease, he was buried at the convent in as plain and humble manner as the poorest member of the community. Thus, in obscurity, and dependent on the charity of a few poor monks, died Philip Duke of Wharton-the possessor of six peerages, the inheritor of a lordly castle, and two other noble mansions, with ample estates, and endowed with talents that might have raised him to wealth and reputation, had he been born in poverty and obscurity. By his death his family, long the pride of the north, and all his titles, became extinct. The remnant of his estates was sold to pay his debts; and his widow, who survived him many years, lived in great privacy in London, on a small pension from the court of Spain. Not long before he died, he sent to a friend in England a manuscript tragedy on Mary Queen of Scots, and some poems; and finished his letter with these lines from Dryden: Be kind to my remains; and oh! defend Against your judgment your departed friend! Let not the insulting foe my fame pursue, But shade those laurels that descend to you. Notwithstanding this piteous appeal, Pope has enshrined his character in the following lines: Clodio-the scorn and wonder of our days, Whose ruling passion was the lust of praise; Born with whate'er could win it from the wise, Women and fools must like him, or he dies; Though wondering senates hung on all he spoke, The club must hail him master of the joke. Shall parts so various aim at nothing new? He'll shine a Tully and a Wilmot too. Thus, with each gift of nature and of art, And wanting nothing but an honest heart; Grown all to all, from no one vice exempt, And most contemptible to shun contempt; His passion still to covet general praise, His life to forfeit it a thousand ways: His constant bounty no one friend has made; His angel tongue no mortal can persuade; A fool, with more of wit than half mankind, Too quick for thought, for action too refined; A tyrant to the wife his heart approves, A rebel to the very king he loves; He dies, sad outcast of each church and state, And, harder still! flagitious, yet not great. Ask you, why Clodio broke through every rule? 'Twas all for fear the knaves should call him fool What riches give us, let us first inquire: Meat, fire, and clothes. What more? Meat, clothes, and fire. Is this too little? Would you more than live? Alas! 'tis more than Turner finds they give; Alas! 'tis more than-all his visions past- Unhappy Wharton, waking, found at last! CHARLOTTE BRONTEAt the end of 1847, a novel was published which quickly passed from professed readers of fiction into the hands of almost every one who had any interest in English literature. Grave business men, who seldom adventured into lighter reading than the Times, found themselves sitting until past midnight entranced in its pages, and feverish. with curiosity until they had en-grossed the final mystery of its plot. Devoured by excitement, many returned to its pages to note anew its felicities of diction, and the graphic, if sometimes rude force, with which character, scenery, and events were portrayed. That novel was Jane Eyre, by Currer Bell. Who was Currer Bell? was the world's question. Was Currer a man or a woman? The truth of the case was so surprising as to be quite out of the range of conjecture. Jane Eyre, a work which in parts seemed welded with the strength of a Titan, was the performance of a delicate lady of thirty, who had little experience of the world beyond her father's lonely parsonage of Haworth, set high among the bleak Yorkshire moors. Even her father did not learn the secret of his daughter's authorship until her book was famous. One afternoon she went into his study, and said: 'Papa, I've been writing a book.' 'Have you, my dear?' 'Yes; and I want you to read it.' 'I am afraid it will try my eyes too much.' 'But it is not in manuscript, it is printed.' 'My dear! you've never thought of the expense it will be! It will be almost sure to be a loss, for how can you get a book sold? No one knows you or your name.' 'But, papa, I don't think it will be a loss; no more will you, if you will just let me read you a review or two, and tell you more about it.' So she sat down and read some of the reviews to her father; and then, giving him a copy of Jane Eyre, she left him to read it. When he came in to tea, he said, 'Girls, do you know Charlotte has been writing a book, and it is much better than likely?' This Charlotte was the daughter of the Rev. Patrick Bronte, a tall and handsome Irishman, from County Down, who in 1812 married Miss Branwell, an elegant little Cornishwoman from Penzance. They had six children, one son and five daughters, who were left motherless by Mrs. Bronte's premature death in 1821. Within a few years, two of her girls followed her to the tomb, leaving Charlotte, Emily Jane, Anne, and Patrick Branwell survivors. A stranger group of four old-fashioned children-shy, pale, nervous, tiny, and precocious-was probably never seen. Their father was eccentric and reserved; and, thrown on their own resources for amusement, they read all that fell into their hands. They wrote tales, plays, and poems; edited imaginary newspapers and magazines; and dwelt day by day in a perfect dream world. These literary tastes formed in childhood strengthened as the sisters grew in years; and amid many and bitter cares, they were not the least among their sources of solace. Their first venture into print was made in 1846. It consisted of a small volume of Poems, by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, the initials of each name being alone true. The book excited little attention, and brought them neither money nor fame. They next resolved to try their hands at novels; and Charlotte wrote The Professor, Emily Wuthering Heights, and Anne Agnes Grey. Emily's and Anne's novels were accepted by publishers; but none would have Charlotte's. Then it was that, undaunted by disappointment and rebuffs, she set to work and produced Jane Eyre, which was followed in 1849 by Shirley, and in 1852 by Villette. The family affections of the Brontes were of the deepest and tenderest character, and in them it was their sad lot to be wounded again and again. Their brother Branwell, on whom their love and hopes were fixed, fell into vice and dissipation; and, after worse than dying many times, passed to his final rest in September 1848, at the age of thirty. Haworth parsonage was unhealthily situated by the side of the grave-yard, and the ungenial climate of the moors but ill accorded with constitutions exotic in their delicacy. Ere three months had elapsed from Branwell's death, Emily Jane glided from earth, in her twenty-ninth year; and within other six months Anne followed, at the age of twenty-seven, leaving poor Charlotte alone with her aged father. It was a joy to all to hear that on the 29th of June 1854 she had become the wife of the Rev. A. Bell Nicholls, who for years had been her father's curate, and had daily seen and silently loved her. The joy however was soon quenched, for on the 31st May 1855 Charlotte also died, before she had attained her fortieth year. Last of all, in 1861 the Bronte family became extinct with the decease of the father, at the advanced age of eighty-four. CECILY, DUCHESS OF YORK Cecily, Duchess of York, who died on the 31st May 1495, was doomed to witness in her own family more appalling calamities than probably are to be found in the history of any other individual. She was a Lancastrian by birth, her mother being Joan Beaufort, a daughter of John of Gaunt. Her father was that rich and powerful nobleman, Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmoreland. She was the youngest of twenty-one children, and, on her becoming the wife of Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, her numerous, wealthy, and powerful family exerted all their influence to place her on the throne of England. But, after a series of splendid achievements, almost unparalleled in history, the whole family of the Nevilles were swept away, long before their sister Cecily-who by their conquering swords became the mother of kings-had descended in sorrow to the grave. To avoid confusion, the sad catalogue of her misfortunes requires to be recorded in chronological order. Her nephew, Humphrey, Earl of Stafford, was killed at the first battle of St Albans, in 1455. Her brother-in-law, Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, was killed at the battle of Northampton, in 1460. Her husband, Richard, Duke of York, was slain in 1460, at the battle of Wakefield, just as the crown of England was almost within his ambitious grasp. Her nephew, Sir Thomas Neville, and her husband's nephew, Sir Edward Bourchier, were killed at the same time and place. Her brother, the Earl of Salisbury, was taken prisoner, and put to death after the battle; and her son Edmund, Earl of Rutland, a boy but twelve years of age, was captured when flying with his tutor from the fatal field, and cruelly murdered in cold blood by Lord Clifford, ever after surnamed the Butcher. Her nephew, Sir John Neville, was killed at the battle of Towton, in 1461; and her nephew, Sir Henry Neville, was made prisoner and put to death at Banbury, in 1469. [To learn more about these War of the Roases's battles, we suggest you read the entry on Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, 'the king-maker.] Two other nephews, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, 'the king-maker,' and John Neville, Marquis of Montague, were killed at the battle of Barnet, in 1471. Edward, Prince of Wales, who married her great niece, was barbarously murdered after the battle of Tewkesbury, in the same year. Her son George, Duke of Clarence, was put to death-drowned in a malmsey butt, as it is said-in the Tower of London, in 1478, his wife Cecily having previously been poisoned. Her son-in-law, Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, was killed at the battle of Nancy, in 1477. Her eldest son, Edward the Fourth, King of England, fell a victim to his passions in the prime of manhood, in 1483. Lord Harrington, the first husband of her niece, Catherine Neville, was killed at Wakefield; and Catherine's second husband, William Lord Hastings, was beheaded, without even the form of a trial, in 1483. Her great nephew Vero, son of the Earl of Oxford, died a prisoner in the Tower, his father being in exile and his mother in poverty. Her son-in-law, Holland, Duke of Exeter, who married her daughter Anne, lived long in exile, and in such poverty as to be compelled to beg his bread; and in 1473 his corpse was found stripped naked on the sea-shore, near Dover. Her two grandsons, King Edward V and Richard Duke of York, were murdered in the Tower in 1483. Her son-in-law, Sir Thomas St. Ledger, the second husband of her daughter Anne, was executed at Exeter in 1483; and her great-nephew, Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, was beheaded at or about the same time. Her grandson, Edward, Prince of Wales, son of Richard III, through whom she might naturally expect the honour of being the ancestress of a line of English kings, died in 1484, and his mother soon followed him to the tomb. Her youngest son, Richard III, was killed at Bosworth Field, in 1485; and her grandson, John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, was slain at the battle of Stoke in 1487. Surviving all those troubles, and all her children, with the sole exception of Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy, she died at a good old age, after seeing three of her descendants kings of England, and her grand-daughter, Elizabeth, queen of Henry VII. By her death, she was saved the additional affliction of the loss of her grandson, Edward, Earl of Warwick, the last male of the princely house of Plantagenet, who was tyrannically put to death by a cruel and jealous monarch in 1499. When her husband was killed at the battle of Wakefield, the conquerors cut off his head, and putting a paper crown on it, in derision of his royal claims, placed it over the principal gate of the city of York. But when her son Edward came to the throne, he caused the mangled remains of his father to be collected, and buried with regal ceremonies in the chancel of the Collegiate Church at Fotheringay, founded and endowed by the piety and liberality of his ancestors. And Cecily, according to directions contained in her will, was buried at Fotheringay, beside the husband whose loss she had mourned for thirty-five long years. It was fated that she was to be denied the last long rest usually allotted to mortals. At the Reformation, the Collegiate Church of Fotheringay was razed to the ground, and the bodies of Richard and Cecily, Duke and Duchess of York, were exposed to public view. A Mr. Creuso, who saw them, says: Their bodies appeared very plainly, the Duchess Cecily had about her neck, hanging on a ribbon, a pardon from Rome, which, penned in a fine Roman hand, was as fair and fresh to be seen as if it had been written the day before. The discovery having been made known to Queen Elizabeth, she ordered the remains to be carefully reinterred, with all decent solemnities. THE COTSWOLD GAMESThe range of hills overlooking the fertile and beautiful vale of Evesham is celebrated by Drayton, in his curious topographical poem, the Poly-Olbion, as the yearly meeting-place of the country folks around to exhibit the best bred cattle, and pass a day in jovial festivity. He pictures these rustics dancing hand-in-hand to the music of the bagpipe and tabor, around a flag-staff erected on the highest hill-the flag inscribed 'Heigh for Cotswold! '-while others feasted upon the grass, presided over by the winner of the prize. The Shepherds' King Whose flock bath chanced that year the earliest lamb to bring, In his gay baldrick sits at his low grassy board, With flawns, lards, clowtcd cream, and country dainties stored; And, whilst the bagpipe plays, each lusty jocund swain Quaffs sillibubs in cans to all upon the plain, And to their country girls, whose nosegays they do wear, Some roundelays do sing; the rest the burthen bear.  The description pleasantly, but yet painfully, reminds us of the halcyon period in the history of England procured by the pacific policy of Elizabeth and James I, and which apparently would have been indefinitely prolonged-with a great progress in wealth and all the arts of peace-but for the collision between Puritanism and the will of an injudicious sovereign., which brought about the civil war. The rural population were, during James's reign, at ease and happy; and their exuberant good spirits found vent in festive assemblages, of which this Cotswold meeting was but an example. But the spirit of religious austerity was abroad, making continual encroachments on the genial feelings of the people; and, rather oddly, it was as a countercheck to that spirit that the Cotswold meeting attained its full character as a festive assemblage. There lived at that time at Burton-on-the-Heath, in Warwickshire, one Robert Dover, an attorney, who entertained rather strong views of the menacing character of Puritanism. He deemed it a public enemy, and was eager to put it down. Seizing upon the idea of the Cotswold meeting, he resolved to enlarge and systematize it into a regular gathering of all ranks of people in the province-with leaping and wrestling, as before, for the men, and dancing for the maids, but with. the addition of coursing and horse-racing for the upper classes. With a formal permission from King James, he made all the proper arrangements, and established the Cotswold games in a style which secured general applause, never failing each year to appear upon the ground himself-well mounted, and accoutred as what would now be called a master of the ceremonies. Things went on thus for the best part of forty years, till (to quote the language of Anthony Wood), 'the rascally rebellion was begun by the Presbyterians, which gave a stop to their proceedings, and spoiled all that was generous and ingenious elsewhere.' Dover himself, in milder strains, thus tells his own story: I've heard our fine refined clergy teach, Of the commandments, that it is a breach To play at any game for gain or coin; 'Tis theft, they say-men's goods you do purloin; For beasts or birds in combat for to fight, Oh, 'tis not lawful, but a cruel sight. One silly beast another to pursue 'Gainst nature is, and fearful to the view; And man with man their activeness to try Forbidden is-much harm doth come thereby; Had we their faith to credit what they say, We must believe all sports are taken away; Whereby I see, instead of active things, What harm the same unto our nation brings; The pipe and pot are made the only prize Which all our spriteful youth do exercise. The effect of restrictions upon wholesome out-of-doors amusements in driving people into sotting public-houses is remarked in our own day, and it is curious to find Mr Dover pointing out the same result 250 years ago. His poem occurs at the close of a rare volume published in 1636, entirely composed of commendatory verses on the exploits at Cotswold, and entitled Annalia Dubrensia. Some of the best poets of the day contributed to the collection, and among them were Ben Jonson, Michael Drayton, Thomas Randolph, Thomas Heywood, Owen Feltham, and Shackerly Marmyon. 'Rare Ben' contributed the most characteristic effusion of the series, which, curiously enough, he appears to have overlooked, when collecting such waifs and strays for the volume he published with the quaint title of Underwoods; neither does it appear in his Collection of Epigrams. He calls it 'an epigram to my jovial good friend, Mr. Robert Dover, on his great instauration of hunting and dancing at Cotswold.' I cannot bring my Muse to drop vies 'Twixt Cotswold and the Olympic exercise; But I can tell thee, Dover, how thy games Renew the glories of our blessed James: How they do keep alive his memory With the glad country and posterity; How they advance true love, and neighbourhood, And do both church and commonwealth the good- In spite of hypocrites, who are the worst Of subjects; let such envy till they burst. Drayton is very complimentary to Dover: We'll have thy statue in some rock cut out, With brave inscriptions garnished about; And under written-' Lo! this is the man Dover, that first these noble sports began.' Lads of the hills and lasses of the vale, In many a song and many a merry tale, Shall mention thee; and, having leave to play, Unto thy name shall make a holiday. The Cotswold shepherds, as their flocks they keep, To put off lazy drowsiness and sleep, Shall sit to tell, and hear thy story told, That night shall comc ere they their flocks can fold. The remaining thirty-one poems, with the exception of that by Randolph, have little claim to notice, being not unfrequently turgid and tedious, if not absurdly hyperbolical. They are chiefly useful for clearly pointing out the nature of these renowned games, which are also exhibited in a quaint wood-cut frontispiece. In this, Dover (in accordance with the antique heroic in art) appears on horseback, in full costume, three times the size of life; and bearing in his hand a wand, as ruler of the sports. In the central summit of the picture is seen a castle, from which volleys were fired in the course of the sports, and which was named Dover Castle, in honour of Master Robert; one of his poetic friends assuring him --thy castle shall exceed as far The other Dover, as sweet peace doth war! This redoubtable castle was a temporary erection of woodwork, brought to the spot every year. The sports took place at Whitsuntide, and consisted of horse-racing (for which small honorary prizes were given), hunting, and coursing (the best dog being rewarded with a silver collar), dancing by the maidens, wrestling leaping, tumbling, cudgel-play, quarter-staff, casting the hammer, &c., by the men. Tents were erected for the gentry, who came in numbers from all quarters, and here refreshments were supplied in abundance; while tables stood in the open air, or cloths were spread on the ground, for the commonalty. None ever hungry from these games come home, Or e'er make plaint of viands or of room; He all the rank at night so brave dismisses, With ribands of his favour and with blisses. Horses and men were abundantly decorated with yellow ribbons (Dover's colour), and he was duly honoured by all as king of their sports for a series of years. They ceased during the Cromwellian era, but were revived at the Restoration; and the memory of their founder is still preserved in the name Dover's Hill, applied to an eminence of the Cotswold range, about a mile from the village of Campden. Shakspeare, whose slightest allusion to any subject gives it an undying interest, has immortalized these sports. Justice Shallow, in his enumeration of the four bravest roisterers of his early days, names 'Will Squell, a Cotswold man;' and the mishap of Master Page's fallow greyhound, who was 'out-run on Cotsale,' occupies some share of the dialogue in the opening scene of the Merry Wives of Windsor. |