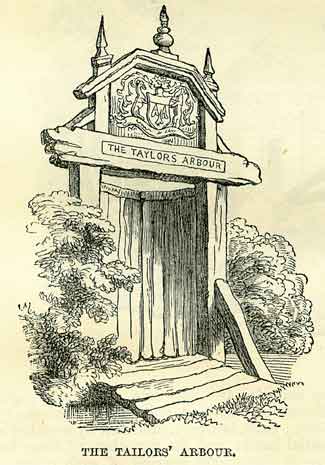

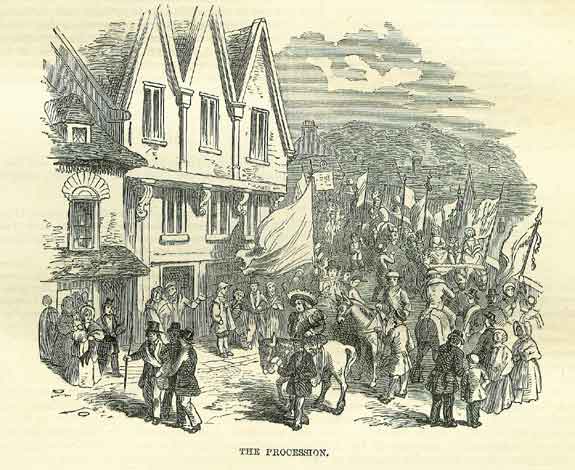

30th MayBorn: Peter the Great, of Russia, 1672, Moscow; Henry Viscount Sidmouth, statesman, 1757, Reading; Jolm Charles, third Earl Spencer, Chancellor of the Exchequer (1830-4), 1782; Samuel Spalding, writer in physiology, theory of morals, and biblical criticism, 1807, London. Died: King Arthur, 542; St. Hubert, 727, Ardennes; Jerome of Prague, religious reformer, burnt at Constance, 1416; Joan d'Arc, burnt at Rouen, 1431; Charles IX of France, 1574, Vincennes; Peter Paul Rubens, painter, 1640; Charles Montagu, Earl of Halifax, statesman, 1715; Alexander Pope, poet, 1744, Twickenham; Elizabeth Elstob, learned in Anglo-Saxon, 1756, Bulstrode; Voltaire, 1778, Paris. Feast Day: St. Felix, pope and martyr, 274. St. Maguil, recluse in Picardy, about 685. St. Walstan, farm labourer at Taverham in Norfolk, devoted to God, 1016. St. Ferdinand III, first king of Castile and Leon in union, 1252. KING ARTHURAccording to British story, at the time when the Saxons were ravaging our island, but had not yet made themselves masters of it, the Britons were ruled by a wise and valiant king, named Uther Pendragon. Among the most distinguished of Uther's nobles was Gorlois Duke of Cornwall, whose wife Igerna was a woman of surpassing beauty. Once, when King Uther was as usual holding his royal feast of Easter, Gorlois attended with his lady; and the king, who had not seen her before, immediately fell in love with her, and manifested his passion so openly, that Gorlois took away his wife abruptly, and went home with her to Cornwall without asking for Uther's leave. The latter, in great anger, led an army into Cornwall to punish his offending vassal, who, conscious of his inability to resist the king in the field, shut up his wife in the impregnable castle of Tintagel, while he took shelter in another castle, where he was immediately besieged by the formidable Uther Pendragon. During the siege, Uther, with the assistance of his magician, Merlin, obtained access to the beautiful Igerna in the same manner as Jupiter approached Alcmena, namely, by assuming the form of her husband; the consequence was the birth of the child who was destined to be the Hercules of the Britons, and who when born was named Arthur. In the sequel, Gorlois was killed, and then Uther married the widow. Such, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth, and the so-called British historians, was the origin of King Arthur. On the death of Tither, Arthur was unanimously chosen to succeed him, and was crowned at Silchester. No sooner had he ascended the throne than he was called upon to war against the Saxons, who, under a new chief named Colgrin, had united with the Picts and Scots, and made themselves masters of the northern parts of the island. With the assistance of his nephew, Hoel, King of Brittany, Arthur overcame the Anglo-Saxons, and made them promise to leave the island. But, instead of going to their own country, they only sailed round the coasts, and landing again at Totness, laid waste the country with fire and sword till they reached the city of Bath, which they besieged. Arthur, leaving his nephew Hoel sick at Alcluyd (Dunbarton), hastened south-ward to encounter the invaders, and defeated them with great slaughter at a place which is called in the story Mount Badon. Having thus crushed the Saxons, Arthur returned to Alcluyd, and soon reduced the Picts and Scots to such a condition, that they sought shelter in the islands in Loch Lomond, and there made their peace with him. Not content with these successes, Arthur next conquered Ireland, Iceland, Gothland, and the Orcades; to which he afterwards added Norway and Denmark, placing over them all tributary kings chosen from among his own chieftains. Next he turned his arms against Gaul, which also he subdued, having defeated and slain its governor Flollo in single combat, under the walls of Paris. The conquest of the whole of Gaul occupied nine years, at the end of which Arthur returned to Paris, and there distributed the conquered provinces among his followers. Arthur was now in the zenith of his power, and on his return to his native land he made a proud display of his greatness, by calling to a great council at Caerleon all these tributary princes, and there in great pomp he was crowned again. Before the festivities were ended, an unexpected occurrence turned the thoughts of the assembled princes to new adventures. Twelve aged men arrived as ambassadors from Lucius Tiberius, the 'procurator' of the republic of Rome, bearing a letter by which King Arthur was summoned in peremptory language to restore to Rome the provinces which he had unjustly usurped on the Continent, and also to pay the tribute which Britain had formerly paid to the Imperial power. A great council was immediately held, and it was resolved at once to retort by demanding tribute of Rome, and to march an army immediately into Italy, to subdue the Imperial city. Arthur next entrusted the government of Britain to his nephew Modred and his queen Guanhumara, and then embarked at Southampton for the Continent. They landed near Mont St. Michael, where Arthur slew a Spanish giant, who had carried away Helena, the niece of Hoel of Brittany. The army of the Britons now proceeded on their march, and soon encountered the Romans, who had advanced into Gaul to meet them; but who, after much fighting and great slaughter, were driven out of the country, with the loss of their commander, Lucius Tiberius, who was slain by Arthur's nephew, Walgan, the Gawain of later romance. At the approach of the following spring, King Arthur began his march to Rome, but as he was beginning to pass the Alps he was arrested by disastrous news from Britain. Modred, who had been left there as regent during the absence of the king, conspired with the queen, whom he married, and usurped the crown; and he had called in a new horde of Saxons to support him in his usurpation. On hearing of these events, Arthur divided his forces into two armies, one of which he left in Gaul, under the command of Hoel of Brittany, while with the other he passed over to Britain, and landed at Rutupiae, or Richborough, in Kent, where Modred awaited them with a powerful army. Although Arthur lost a great number of his best men, and among the rest his nephew Walgan, Modred was defeated and put to flight, and he was only able to rally his troops when he reached Winchester. When the news of this defeat reached the queen, who was in York, she fled to Caerleon, and took refuge in a nunnery, where she resolved to pass the remainder of her life in penitence. Arthur followed his nephew to Winchester, and there defeated him in a second battle; but Modred escaped again, and made his retreat towards Cornwall. He was overtaken, and finally defeated in a third battle, which was far more obstinate and fatal than those which preceded. Modred was slain, and King Arthur himself was mortally wounded. They carried him to the Isle of Avallon (Glastonbury), to be cured of his wounds; but all the efforts of the physicians were vain, and he died and was buried there, Geoffrey of Monmouth says, in the year 542. Before his death, he resigned the crown to his kinsman Constantine. Such is an outline of the fabulous history of King Arthur, as it is given by the earliest narrator, Geoffrey of Monmouth, who wrote in the year 1147. The numerous stories of King Arthur, and his knights of the round table, which now swell out the story, are the works of the romance writers of later periods. There was a time when every writer or reader of British history was expected to put entire faith in this narrative; but that faith has gradually diminished, until it has become a matter of serious doubt whether such a personage ever existed. There are few indeed now who take Geoffrey of Monmouth's history for anything but fable. The name of a King Arthur was certainly not known to any chroniclers in this country before the Norman period, and Giraldus Cambrensis, towards the end of the twelfth century, bears testimony to the fact that Geoffrey's stories wore not Welsh. From different circumstances connected with their publication, it seems probable that they were derived from Brittany, and one of the opinions regarding them is that Arthur may have been a personage in the mythic history of the Bretons. However, be this as it may, the history of King Arthur has become an important part of our literature; and as it sinks lower in the estimate of the historian, it seems to have become more popular than over, and to have increased in favour with the poet. In proof of this, we need only point to Tennyson and Bulwer. JOAN D'ARCWhen Horace Walpole wished to amuse his father by reading a historical work to him, the aged statesman, 'hackneyed in the ways of men,' exclaimed-'Anything but history; that must be false.' Dr. Johnson, according to Boswell, held a somewhat similar opinion; and Gibbon, alluding to the fallacies of history, said, 'the spectators of events knew too little, the actors were too deeply interested, to speak the real truth.' The French heroine affords a remarkable instance of historic uncertainty. Historians, one copying the words of another, assert she was burned at Rouen, in 1431; while documentary evidence of the most authentic character, completely negativing the story of her being burned, shew she was alive, and happily married, several years after the period alleged to be that of her execution. Many of these documents are in the registry of the city of Mentz, and prove she came thither in 1436. The magistrates, to make sure that she was not an impostor, sent for her brothers, Pierre and Jean, who at once recognised her. Several entries in the city records enumerate the presents, with the names of the donors, that were given to her on the occasion of her marriage with the Chevalier d'Armoise, and even the marriage contract between Robert d'Armoise, Knight, and Jeanne d'Arc, la Pucelle d'Orleans, has been discovered. The archives of the city of Orleans contain important evidence on this subject. In the treasurer's accounts for 1435, there is an entry of eleven francs and eight sous paid to messengers who had brought letters from 'Jeanne, la Pucelle.' Under the date of 1436, there is another entry of twelve livres paid to Jean de Lys, brother of Jeanne, la Pucelle,' that he might go and see her. The King of France ennobled Joan's family, giving them the appellation of de Lys, derived from the fleur de lys, on account of her services to the state; and the entry in the Orleans records corresponds with and corroborates the one in the registry of Mentz, which states that the magistrates of the latter city sent for her brothers to identify her. These totally independent sources of evidence confirm each other in a still more remarkable manner. In the treasurer's accounts of Orleans for the year 1439, there are entries of various sums expended for wine, banquets, and public rejoicings, on the occasion of Robert d'Armoise and Jeanne, his wife, visiting that city. Also a memorandum that the council, after mature deliberation, had presented to Jeanne d'Armoise the sum of 210 livres, for the services rendered by her during the siege of the said city of Orleans. There are several other documents, of equally unquestionable authority, confirming those already quoted here; and the only answer made to them by persons who insist that Joan was burned is, that they are utterly unexplainable. It has been urged, however, that Dame d'Armoise was an impostor; but if she were, why did the brothers of the real Joan recognise and identify her? Admitting that they did, for the purpose of profiting by the fraud, how could the citizens of Orleans, who knew her so well, and fought side by side with her during the memorable siege, allow themselves to be so grossly deceived? The idea that Joan was not burned, but another criminal substituted for her, was so prevalent at the period, that there are accounts of several impostors who assumed to be her, and of their detection and punishment; but we never hear of the Dame d'Armoise having been punished. In fine, there are many more arguments in favour of the opinion that Joan was not burned, which need not be entered into here. The French antiquaries, best qualified to form a correct opinion on the subject, believe that she was not burned, but kept in prison until after the Duke of Bedford's death, in 1435, and then liberated; and so we may leave the question-a very pretty puzzle as it stands. POPE'S GARDENIf we could always discover the personal tastes and pleasurable pursuits of authors, we should find these the best of comments on their literary productions. The outline of our life is generally the work of circumstance, and much of the filling-in is done after an acquired manner; but the fancies a man indulges when he gives the reins to his natural disposition are the clearest index of his mind. No one will deny to Pope excellence of a certain sort. Though, in his verse, we look in vain for the spontaneous and elegant simplicity of nature, yet, in polish and finish, and artificial skill, he stands unrivalled among English poets. And apropos of this ought to be noted how much time and skill he expended on his garden. Next to his mother and his fame, this he loved best. He altered it and trimmed it like a favourite poem, and was never satisfied he had done enough to adorn it. Himself a sad slip of nature, with a large endowment of sensitiveness and love of admiration, he was never very anxious to appear in public-indeed, had he wished, being such an invalid as he was, it would have been out of his power; so he settled at Twickenham, where Lord Bacon and many other literary celebrities had lived before him, and adorned his moderate acres with the graces of artificial elegance. Here, during many long years, he cherished his good mother-and here, when she died, he built a tomb, and planted mournful cypress; here he penned and planned, with his intimate friends, deep designs to overthrow his enemies, and to astonish the world, or listened to philosophy for the use of his Essay on Man, or clipped and filed his elegant lines and sharp-toothed satires. When we read of Pope's delightful little sanctum, when we hear Walpole describing 'the retiring and again assembling shades, the dusky groves, the larger lawn, and the solemnity of the termination at the cypresses that led up to his mother's tomb,' we almost wonder that so much envy and spite, and filthiness and bitter hatred, could there find a hiding-place. Such hostility did the publication of the Dunciad-in which he lashed unmercifully all his literary foes, and many who had given him no cause of offence-bring upon the reckless satirist, that his sanctuary, it is hinted, might for a short time have been considered a prison. He was threatened with a cudgelling, and afraid to venture forth. His old friends and new enemies, Lady Mary Montagu and Lord Hervey, seized upon this opportunity of annoying him, and jointly produced a pamphlet, of which the following was the title: A Pop 'upon Pope; or a true and faithful account of a late horrid and barbarous whipping, committed on the body of Sawney Pope, poet, as he was innocently walking in Ham Walks, near the River Thames, meditating verses for the good of the public. Supposed to have been done by two evil-disposed persons, out of spite and revenge for a harmless lampoon which the said poet had writ upon them. So sensitive was Pope, that believing this fabulous incident would find people to credit it, he inserted in the Daily Post, June 14, 1728, a contradiction: Whereas there has been a scandalous paper cried aloud about the streets, under the title of a Pop 'upon Pope, insinuating that I was whipped in Ham Walks on Thursday last; this is to give notice, that I did not stir out of my house at Twickenham on that day, and the same is a malicious and ill-grounded report.-A. P. That part of Pope's garden which has always excited the greatest curiosity was the grotto and subterraneous passage which he made. Pope himself describes them thus fully in 1725:- I have put my last hand to my works of this kind, in happily finishing the subterraneous way and grotto. I there formed a spring of the clearest water, which falls in a perpetual rill that echoes through the cavern day and night. From the River Thames you see through my arch up a walk of the wilderness to a kind of open temple, wholly composed of shells in a rustic manner, and from that distance under the temple you look down through a sloping arcade of trees, and see the sails on the river passing suddenly and vanishing, as through a perspective glass. When you shut the doors of this grotto, it becomes on the instant, from a luminous room, a camera obscura; on the walls of which. all objects of the river-hills, woods, and boats-are forming a moving picture in their visible radiations; and when you have a mind to light it up, it affords you a very different scene. It is finished with shells, interspersed with pieces of looking-glass in angular forms; and in the ceiling is a star of the same material, at which, when a lamp (of an orbicular figure of thin alabaster) is hung in the middle, a thousand pointed rays glitter, and are reflected over the place. There are connected to this grotto by a narrower passage two porches, one towards the river, of smooth stones, full of light, and open; the other towards the gardens, shadowed with trees, rough with shell, flints, and iron ore. The bottom is paved with simple pebble, as is also the adjoining walk up the wilderness to the temple, in the natural taste agreeing not ill with the little dripping murmur and the aquatic idea of the whole place. It wants nothing to complete it but a good statue with an inscription, like the beautiful antique one which you know I am so fond of: Hujus Nympha loci, sacri custodia fontis, Dormio, dum blandae sentio murmur aquae; Parce meum, quisquis tangis cava murmura, somnum Rumpere, si bibas, sive lavare, tace. Nymph of the grot, these sacred springs I keep, And to the murmur of these waters sleep; Ah! spare my slumbers, gently tread the cave, And drink in silence, or in silence lave. You'll think I have been very poetical in this description, but it is pretty near the truth. I wish you were here to bear testimony how little it owes to art, either the place itself or the image I give of it.' It would be easy to draw a parallel between this grotto and the poet's mind, and instructive to compare the false taste, and eloquence, and pettiness of both. But let us rather, at this present time, hear what became of it. Dodsley, in his Cave of Pope, foreshadows its future fate: Then some small gem, or moss, or shining ore, Departing, each shall pilfer: in fond hope To please their friends in every distant shore, Boasting a relic from the cave of Pope. The inevitable destiny came in due time. The poet's garden first disappeared. Horace Walpole writes to Horace Mann in 1760: I must tell you a private woe that has happened to me in my neighbourhood. Sir William Stanhope bought Pope's house and garden. The former was so small and bad, one could not avoid pardoning his hollowing out that fragment of the rock of Parnassus into habitable chambers; but-would you believe it?-he has cut down the sacred groves themselves. In short, it was a little bit of ground of five acres, enclosed with three lanes, and seeing nothing. Pope had twisted and twirled, and rhymed and harmonized this, till it appeared two or three sweet little lawns opening and opening beyond one another, and the whole surrounded with thick, impenetrable woods. Sir William, by advice of his son-in-law, Mr. Ellis, has hacked and hewed these groves, wriggled a winding gravel walk through them, with an edging of shrubs, in what they call modern taste, and, in short, desired the three lanes to walk in again; and now is forced to shut them out again by a wall, for there was not a Muse could walk there but she was spied by every country fellow that went by with a pipe in his mouth. Pope's house itself was pulled down by Lady Howe (who purchased it in 1807), in order that she might be rid of the endless stream of pilgrims. THE SHREWSBURY SHOWThree remarkable examples of the pageantry of the Middle Ages, in rather distant parts of England, remain at present as the only existing representatives of this particular branch of medieval manners - the Preston Guild, the festival of the Lady Godiva at Coventry, and the Shrewsbury Show. Attempts have recently been made in each of these cases to revive customs which had already lost much of their ancient character, and which appeared to be becoming obsolete; but probably with only temporary success. It is not, indeed, easy, through the great changes of society, to make permanent customs which belong exclusively to the past. The municipal system of the Middle Ages, and the local power and influence of the guild, which alone supported these customs, have themselves passed away. As in other old towns, the guilds or trading corporations of Shrewsbury were numerous, and had no doubt existed from an early period-all these fraternities or companies were in existence long before they were incorporated. The guilds of the town of Shrewsbury presented one peculiarity which, as far as we know, did not exist elsewhere. On the southern side of the town, separated from it by the river, lies a large space of high. ground called Kingsland, probably because in early times it belonged to the kings of Mercia. At a rather remote period, the exact date of which appears not to be known, this piece of ground came into the possession of the corporation; and it has furnished during many ages a delightful promenade to the inhabitants, pleasant by its healthful air and by the beautiful views it presents on all sides. It was on this spot that the Shrewsbury guilds held their great annual festivities, and hither they directed the annual procession which, as in other places, was held about the period of the feast of Corpus Christi. The day of the Shrewsbury Show, which appears from records of the reign of Henry VI to have then been held 'time out of mind,' is the second Monday after Trinity Sunday. At some period, which also is not very clearly known, portions of land were distributed to the different guilds, who built upon them their halls, or, as they called them, harbours. The word harbour meant properly a place of entertainment, but it is one of the peculiarities of the local dialects on the borders of Wales to neglect the h, and these buildings are now always called arbours. Seven of these arbours are, we believe, still left. They are halls built chiefly of wood, each appropriated to a particular guild, and furnished with a large table (or tables) and benches, on which the members of the guild feasted at the annual festival, and probably on other occasions. Other buildings, sometimes of brick, were attached to the hall, for people who had the care of the place, and a court or space of ground round, generally rectangular, was surrounded by a hedge and a ditch, with an entrance gateway more or less ornamented. These halls appear to have been first built after the restoration of Charles II. The first of which there is any account was that of the Tailors, of which there is the following notice in account books of the Tailors' Company for the year 1661.  Thus the building of the Tailors' arbour cost the sum total of £3,3s. 4d. It was of wood, and underwent various repairs, and perhaps received additions during the following years; and it is still standing, though in a dilapidated condition. Our cut represents the entrance gateway as it now appears, and the bridge over the ditch which surrounds it. The ornamental part above, on which are carved the arms of the Tailors' Company, was erected in 1669, at an expense of £1,10s., as we learn from the same books. Our second cut will give a better general notion of the arrangement of these buildings. It is the Shoemakers' arbour, the best preserved and most interesting of them all. The hall of timber is seen within the enclosure; the upper part is open-work, which admits light into the interior. At the back of it is a small brick house, no doubt more modern than the arbour itself. The gate-way, which is much more handsome than usual, and is built of stone, bears the date of 1679, and the initials, H. P. and E. A., of the wardens of the Shoemakers' guild at that time. At the sides of the arms of the company are two now sadly-mutilated statues of the patron saints of the Shoe-makers, Crispin and Crispinianus, and on the square tablet below the following rather naive rhymes, now nearly effaced, were inscribed: We are but images of stonne, Doe us noe harme, we can doe nonne. The Shearmen's Company (or Clothworkers) had a large tree in their enclosure, with seats ingeniously fixed among the branches, to which those who liked mounted to carouse, while the less venturesome members of the fraternity con-tented themselves with feasting below. Shrewsbury Show has been in former times looked forward to yearly by the inhabitants in general as a day of great enjoyment, although at present it is only enjoyment to the lower orders. Each company marched in their livery, with a pageant in front, preceded by their minstrels or band of music. The pageants were prepared with great labour and expense, the costume, &c., being carefully preserved from year to year. The choice of the subject for the pageant for each guild seems in some cases to have been rather arbitrary-at least during the period of which we have any account of them; and most of them are doubtless entirely changed from the mediaeval pageants. Thus the pageant of the Shearmen represented sometimes King Edward VI, and at others Bishop Blaise. The Shoe-makers have always been faithful to their patron saints, Crispin and Crispinianus. The Tailors have had at different times a queen, understood to represent Queen Elizabeth; two knights, carrying drawn swords; or Adam and Eve, the two latter dressed in aprons of leaves sewed together. The last of these only receive any explanation-the Tailors looked upon Adam and Eve as the first who exercised their craft. The Butchers had as their pageant a personage called the Knight of the Cleaver, who carried as his distinguishing badge an axe or cleaver, and was followed by a number of boys decked gaily with ribbons, and brandishing fencing-swords, who were called his Fencers. The Barber-Chirurgeons and Weavers united in one body, and had for their pageant what is described as 'Catherine working a spinning-wheel,' which was no doubt intended to represent St. Catherine and her wheel, which was anything but a spinning-wheel. The Bricklayers, Carpenters, and Joiners had adopted for their pageant King Henry VIII; but some years ago they deserted the bluff king temporarily for a character called ' Jack Bishop.' The Hatters and Cabinetmakers, for some reason unknown, selected as their pageant an Indian chief, who was to ride on horseback brandishing a spear. The Bakers seem to have studied Latin sufficiently deep to have learnt that sine Cerere friget Venus, and they adopted the two goddesses Venus and Ceres; sometimes giving one and sometimes the other. The pageant of the Skinners and Glovers was a figure of a stag, accompanied by huntsmen blowing horns. The Smiths had Vulcan, whom they clothed in complete armour, giving him two attendants, armed with blunderbusses, which they occasion-ally discharged, to the great delight of the mob. The Saddlers have a horse fully caparisoned, and led by a jockey. The united Printers, Painters, and others, have of late years adopted as their pageant Peter Paul Rubens. It was probably this grouping together of the guilds, in order to distinguish the number of pageants, which has caused the arbitrary selection of new subjects. On some of the late occasions, a new personage was placed at the head of the procession to represent King Henry II, because he granted the first charter to the town.  In the forenoon of the day of the show, the performers usually muster in the court of the castle, and then go to assemble in the market-square, there to be marshalled for the procession. On the occasion at which we were present, in the summer of 1860, the number of pageants was reduced to seven. First came the pageant of the Shoemakers-Crispin, in a bright new leathern doublet, and his martial companion, also in a new suit, both on horseback. Next came a pageant of Cupid and a stag, with what may be supposed to have been intended for his mother, Venus, in a handsome car, raised on a platform drawn by four white horses-the pageant of the Tailors, Drapers, and Skinners. The third pageant was the Knight of the Cleaver, who also had a new suit, and who represented on this occasion the Butchers and Tanners. Henry VIII, his personage padded out to very portly dimensions, in very dashing costume, who might almost have been taken by his swagger for the immortal Falstaff, and carrying a short staff or sceptre in his hand, rode next, as the head of the Bricklayers, Carpenters, and Joiners. Then came the Indian chief, the pageant of the Cabinet-makers, Hatters, and others; followed by Vulcan, representing the Smiths, and who, as usual, was equipped in complete armour; and Queen Catherine (?) as the representative of the Flax-dressers and Thread-manufacturers. The showy ranks of the trades of former times had dwindled into small parties of working men, who marched two and two after each pageant, without costume, or only distinguished by a ribbon; each, however, preceded by a rather substantial band; and the fact that all these bands were in immediate hearing of each other, and all playing at the same time, and not together, will give a notion of the uproar which the whole created. The procession started soon after mid-day, and the confusion was increased by the sudden fall of a shower of rain just at that moment; whereupon Cupid was rendered not a bit more picturesque by having a great-coat thrown over his shoulders, while both he and Venus took shelter under an umbrella. In this manner the procession turned the High Street, and proceeded along Pride Hill and Castle Street round the Castle end of the town-back, and by way of Dogpole and Wylecop, over the English Bridge into the Abbey Foregate. In the course of this perambulation they made many halts, and frequently partook of beer; so that when, after making the circuit of the Abbey Church, they returned over the English Bridge into the town, the procession had lost most of the order which it had observed at starting-whoever represented the guilds had quitted their ranks, and the principal personages were evidently already much the worse for wear. Venus looked sleepy, and Queen Catherine had so far lost all the little dignity she had ever possessed, that she seemed to have a permanent inclination to slip from her horse; while King Henry, looking more arrogant than ever, brandished his sceptre with so little discretion, that an occasional blow on his horse's head caused him every now and then to be nearly ejected from his seat. At the Abbey Foregate the greater part of the crowd deserted, and took the shortest way to Kingsland, while the procession, much more slenderly escorted, returned along the High Street, and proceeded by way of Mardol over the Welsh Bridge, and reached Kingsland through the other suburb of Frankwell.  Our view of the procession, taken from a photograph by a very skilful amateur, made four or five years before the date of the one we have just described, represents it returning disordered and straggling over the English Bridge, and just entering the Wylecop. It will be seen that the guildmen who formed anything like procession have disappeared, and that most of the mob has departed to Kingsland. The man on foot with his rod is the Marshal, who marched in advance of the procession. Behind him comes Henry VIII., with an unmistakable air of weariness, and probably of beer. Behind him are Crispin and Crispinianus, on horseback. Then comes Cupid's car, the god of love seated between two dames, an arrangement which we are unable to explain; a little further we see Vulcan in his suit of armour. Even the musicians are here no longer visible. Formerly, the different guilds, who assembled in considerable numbers, each gave a collation in their particular arbour; and the mayor and corporation proceeded in ceremony and on horse-back from the town to Kingsland, and there visited the different arbours in succession. They were expected to partake in the collation of each, so that the labour in the way of eating was then very considerable. This part of the custom has long been laid aside, and the corporation of Shrewsbury now takes no part personally in the celebration, which is chiefly a speculation among those who profit by it, supported by a few who are zealous for the preservation of old customs. We may form some idea of the style in which the procession was got up in the latter part of the seventeenth century from the items of the expenses of the Tailors' guild in the 'Show' of the year 1687, collected from the records of that guild by Mr. Henry Pidgeon, a very intelligent antiquary of Shrewsbury, to whom we owe a short but valuable essay on the guilds of that town, published some years ago in Eddowes's Shrewsbury Journal. These expenses are as follows (it must be borne in mind that the pageant of the Tailors' Company was the queen, here represented by the 'gyrle'). In 1861, a revival of the show was again attempted, and it was believed that it would be rendered more popular by grafting upon it an exhibition of ' Olympic Games,' including the ordinary old English country pastimes, to which a second day was appropriated; but the attempt was not successful. On this occasion, the ' Black Prince' was introduced as a pageant, to represent the Bakers and Cabinetmakers; and a dispute about the payment of his expenses, which was recently decided in the local court, brought out the following bill of charges, which is quite as quaint as the account of expenses of the Tailors for 1687, given above from the accounts of that guild. 1861. Expenses of one of the stewards of the com-brethren of hatters, cabinetmakers, &c., in the procession to Kingsland, at Shrewsbury Show, and to find a band of music, a herald, and a horse properly caparisoned for the pageant. It remains to be added, that the scene on Kingsland is now only that of a very great fair, with all its ordinary accompaniments of booths for drinking and dancing, shows, &c., to which crowds of visitors are brought by the railways from considerable distances, and which is kept up to a late hour. The 'arbours ' are merely used as places for the sale of refreshments. Towards nine o'clock in the evening the pageants are again arranged in procession to proceed on their return into the town; and as many of the actors as are in a condition to do so take part in them. The arbours and the ground on which they stand have recently been purchased by the corporation from the guild, and are, it is understood, to be all cleared away, preparatory to the enclosure of Kingsland, which has now become a favourite site for genteel villa residences. |