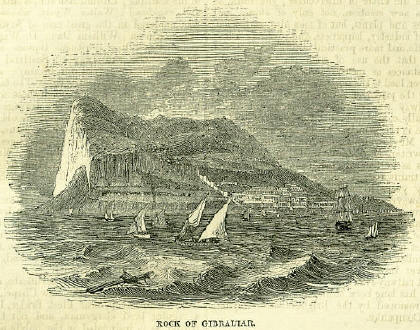

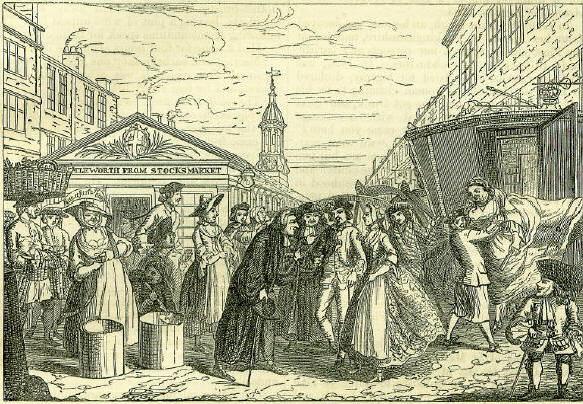

24th JulyBorn: Roger Dodsworth, eminent antiquary, 1585, Newton Grange, Yorkshire; Rev. John Newton, evangelical divine, 1725, London; John Philpot Curran, distinguished Irish barrister, 1750. Died: Caliph Abubeker, first successor of Mohammed, 634, Medina; Don Carlos, son of Philip II of Spain, died in prison, 1568; Alphonse des Vignoles, chronologist, 1744, Berlin; George Vertue, eminent engraver and antiquary, 1756, London; John Dyer, poet, author of Grongar Hill, 1758, Coningsby, Lincolnshire; Dr. Nathaniel Lardner, author of Credibility of the Gospel History, 1768, Hawkhurst, Kent; Jane Austen, novelist, 1817, Winchester; Armand Carrel, French political writer, died in consequence of wounds in a duel, 1836. Feast Day: St. Christina, virgin and martyr, beginning of 4th century. St. Lewine of Britain, virgin and martyr. St. Declan, first bishop of Ardmore, Ireland, 5th century. St. Lupus, bishop of Troyes, confessor, 478. Saints Wulfhad and Ruffin, martyrs, about 670. Saints Romanus and David, patrons of Muscovy, martyrs, 1010. St. Kings, or Cunegundes of Poland, 1292. St. Francis Solano, confessor, 16th century. DON CARLOSThe uncertainty which hangs over the fate of many historical personages, is strikingly exemplified in the case of Don Carlos. That he died in prison at Madrid, on the 24th or 25th of July, is undoubted; but much discrepancy of opinion has prevailed as to whether this event arose from natural causes, or the death-stroke of the executioner, inflicted by the order of his own father, Philip II. The popular account-and, it must also be added, that given by the majority of historians-is that the heir to the Spanish throne met his death by violent means. A wayward and impulsive youth, but, at the same time, brave, generous, and true hearted, his character presents a most marked contrast to that of the cold-blooded and bigoted Philip, between whom and his son it was impossible that any sympathy could exist. The whole course of the youth's upbringing seems to have been in a great measure a warfare with his father; but the first deadly cause of variance, was the marriage of the latter with the Princess Elizabeth of France, who had already been destined as the bride of Don Carlos himself. This was the third time that Philip II had entered the bonds of matrimony. His first wife, Mary of Portugal, died in childbed of Don Carlos; his second was Mary of England, of persecuting memory; and his third, the French princess. By thus selfishly appropriating the affianced bride of another, whose love for her appears to have been of no ordinary description, the overpowering passion of jealousy was added to the many feelings of aversion with which he regarded his son. Many interviews are reported to have taken place between the queen and Don Carlos, but their intercourse appears always to have been of the purest and most Platonic kind. Other causes were contributing, however, to hurry the young prince to his fate. Naturally free and outspoken, his sympathies were readily engaged both on behalf of his father's revolted subjects in the Low Countries, and the Protestant reformers in his own and other nations. Part of his latter predilections has been traced to his residence in the monastery of St. Just with his grandfather, the abdicated Charles V, with whom he was a great favourite, and who, as is alleged, betrayed a leaning to the Lutheran doctrines in his latter days. In regard to his connection with the burghers of the Netherlands, it is not easy to form a definite conclusion; but it appears to be well ascertained, that he regarded the blood-thirsty character of the Duke of Alva with abhorrence, and was determined to free the Flemings from his tyrannical sway. A sympathising letter from Don Carlos to the celebrated Count Egmont is said to have been found among the latter's papers when he and Count Horn were arrested. There seems, also, little reason to doubt that the prince had revolved a plan for proceeding to the Netherlands, and assuming the principal command there in person. This design was communicated by him to his uncle, Don Juan, a natural son of Charles V, who thereupon imparted it to King Philip. The jealous monarch lost no time in causing Don Carlos to be arrested and committed to prison, himself, it is said, accompanying the officers on the occasion. Subsequently to this, there is a considerable diversity in the accounts given by historians. By one class of writers, it is stated that the prince chafed so under the confinement to which he was subjected, that he threw himself into a burning fever, which shortly brought about his death, but not until he had made his peace with his father and the church. The more generally received account is that Philip, anxious to get rid of a son who thwarted so sensibly his favourite schemes of domination, consulted on the subject the authorities of the Inquisition, who gladly gave their sanction to Carlos's death, having long regarded him with aversion for his heretical leanings. Such a deed on the part of a parent, was represented to Philip as a most meritorious act of self sacrifice, and a reference was made to the paternal abnegation recorded in Scripture of Abraham. 'The fanaticism and interest of the Spanish monarch thus combined to overcome any scruples of conscience and filial love still abiding in his breast, and he signed the warrant for the execution of his son, which forthwith took place. The mode in which this was effected is also differently represented: one statement being that he was strangled, and another, that his veins were opened in a bath, after the manner of the Roman philosopher Seneca. The real truth of the sad story must ever remain a mystery; but enough has transpired to invest with a deep and romantic interest the history of the gallant Don Carlos, who perished in the flower of youthful vigour, at the early age of twenty-three, and to cast a dark shade on the memory of the vindictive and unscrupulous Philip II. The story of Don Carlos has formed the subject of at least two tragedies-by Campustron, who transferred the scene to Constantinople, and, in room of Philip II, substituted one of the Greek emperors; and by Schiller, whose noble drama is one of the most imperishable monuments of his genius. JOHN PHILPOT CURRANOratory is the peculiar gift of the Emerald Isle, and, among the crowd of celebrated men whom she can proudly point to, the name of Curran stands preeminent, whether we look at him as a most able lawyer, a first-rate debater, and, in a society boasting of Erskine, Macintosh, and Sheridan, the gayest wit and most brilliant conversationalist of the day. From the village of Newmarket, in Cork, of a poor and low origin, be, at nine years of age, attracted the attention of the rector, the Rev. Mr. Boyse, who sent him to Middleton School, and then to Dublin, where he was 'the wildest, wittiest, dreamiest student of old Trinity;' and, in the event of his being called before the fellows for wearing a dirty shirt, could only plead as an excuse, that he had but one. Poverty followed his steps for some years after this; instead of briefs to argue before the judge, he was amusing the idle crowd in the hall with his wit and eloquence. 'I had a family for whom I had no dinner,' he says, ' and a landlady for whom I had no rent. I had gone abroad in despondence, I came home almost in desperation. When I opened the door of my study, where Lavater could alone have found a library, the first object that presented itself was an immense folio of a brief, and twenty gold guineas wrapped up beside it.' As with many other great lawyers, this was the turning-point; his skill in cross-examination was wonderful, judge and jury were alike amused, while the perjured witness trembled before his power, and the audience were entranced by his eloquence. His first great effort was in 1794, in defence of Archibald Rowan, who had signed an address in favour of Catholic emancipation. In spite of the splendid speech of his advocate, he was convicted; but the mob outside were determined to chair their favourite speaker. Curran implored them to desist, but a great brawny fellow roared out: 'Arrah, blood and turf! Pat, don't mind the little cratur; here, pitch him up this minute upon my showlder!' and thus was he carried to his carriage, and then drawn home. After the miserable rebellion of 1798, it fell to Curran's part to defend almost all the prisoners and, being reminded by Lord Carleton that he would lose his gown, he replied with scorn: 'Well, my lord, his majesty may take the silk, but he must leave the stuff behind!' Most distressing was the task to a man of his sense of justice; the government arrayed against him, and every court filled with the military, yet with swords pointed at him, he cried: 'Assassinate me, you may; intimidate me, you cannot!' Added to this, came domestic sorrow. His beautiful daughter fell in love with the unfortunate Emmet, who was executed in 1803, and she could not survive the shock, but drooped gradually and died; an event which Moore immortalised in his songs, '0 breathe not his name, let it sleep in the shade;' and, 'She is far from the land where her young hero sleeps.' The gloom which had always affected. Curran's mind became more settled; he resigned the Mastership of the Rolls in 1813, and sought alleviation in travelling, but in vain, his death took place at Brompton, on the 14th of October 1817. The witticisms which are attributed to him are numberless. 'Curran,' said a judge to him, whose wig being a little awry, caused some laughter in court, 'do you see anything ridiculous in this wig?' 'Nothing but the head, my lord;' was the reply. One day, at dinner, he sat opposite to Toler, who was called the 'hanging judge.' 'Curran,' said Toler, 'is that hung-beef before you?' 'Do you try it, my lord, and then it's sure to be!' Lundy Foot, the celebrated tobacconist, asked Curran for a Latin motto for his coach. 'I have just hit on it,' said Curran, 'it is only two words, and it will explain your profession, your elevation, and contempt for the people's ridicule; and it has the advantage of being in two languages, Latin and English, just as the reader chooses. Put up, 'Quid rides,' upon your carriage.' The hatred he always felt for those who betrayed their country by voting for the Union, is shewn in the answer he gave to a lord who got his title for his support of the government measure. Meeting Curran near the Parliament House, in College Green, he said: 'Curran, what do they mean to do with this useless building? For my part, I hate the very sight of it.' 'I do not wonder at it, my lord,' said Curran contemptuously, 'I never yet heard of a murderer who was not afraid of a ghost.' CAPTURE AND DEFENSE OF GIBRALTAR BY THE BRITISHIn July 1704, a capture was made, the importance of which has never ceased to be felt: viz., that of Gibraltar by the British. No other rock or headland in Europe, perhaps, equals Gibraltar for commanding position and importance. Situated at the mouth of the Mediterranean, where that celebrated sea is little more than twenty miles wide, the rock has a dominating influence over the maritime traffic of those waters. Not that a cannon-ball could reach a ship at even half that distance; but still the owners of a fortified headland so placed, must necessarily possess great advantages in the event of any hostilities in that sea. The rock is almost an island, for it is connected with the mainland of Spain only by a low isthmus of sand; it is, in fact, a promontory about seven miles in circumference, and 1300 feet high.  At present, a bit of neutral-ground on the sandy isthmus separates Spain from it, politically though not geographically; but in former times, it always belonged to the government, whatever it may have been, of the neighbouring region. The Moors crossed over from Africa, in the eighth century, dethroned the Christian king of Spain, and built a castle on the rock, the ruins of which may still be seen. The Moslems held their rule for 600 years. Gibraltar then changed hands three times during the fourteenth century. After 1492, the Moors never held it. The Christian kings of Spain made various additions to the fortifications during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; but still the defences bore no comparison with those which have become familiar to later generations. Early in the eighteenth century, there was a political contest among the European courts, which led England to support the pretensions of an Austrian prince, instead of those of a Bourbon, to the crown of Spain; and, as a part of the arrangement then made, a combined force proceeded to attack Gibraltar. The Prince of Hesse Darmstadt commanded the troops, and Sir George Rooke the fleet. It is evident either that the Spaniards did not regard the place as of sufficient importance to justify a strenuous defence, or that the defence was very ill-managed; for the attack, commenced on the 21st of July, terminated on the 24th by the surrender of the stronghold. From that day to this, Gibraltar has never for one moment been out of English hands. When it was lost, the Spaniards were mortified and alarmed at their discomfiture; and for the next nine years they made repeated attempts to recapture it, by force and stratagem. On one occasion they very nearly succeeded. A French and Spanish force having been collected on the isthmus, a goat-herd offered to shew them a path up the sloping sides of the rock, which he had reason to believe was unknown to the English. This offer being accepted, 500 troops ascended quietly one dark night, and took shelter in an indenture or hollow called by the Spaniards the silleta, or 'little chair.' At day-break, next morning, they ascended higher, took the signal-station, killed the guard, and anxiously looked round for the reinforcements which were to follow. These reinforcements, however, never came, and to this remissness was due the failure of the attack; for the English garrison, aroused by the surprise, sallied forth, and drove the invaders down the rock again. The silleta was quickly filled up, and the whole place made stronger than ever. When the Peace of Utrecht was signed in 1713, Gibraltar was confirmed to the English in the most thorough and complete way; for the tenth article of that celebrated treaty says: 'The Catholic king (i. e., of Spain) doth hereby, for himself, his heirs, and successors, yield to the crown of Great Britain the full and entire property of the town and castle of Gibraltar, together with the port, fortifications, and forts thereunto belonging; and he gives up the said property to be held and enjoyed absolutely, with all manner of right, for ever, without any exception or impediment what soever.' Towards the close of the reign of George I, about 1726, there were great apprehensions that would yield to the haughty demands of the king of Spain, that Gibraltar should be given up; addresses to the king, deprecating such a step, were presented by lord mayors and mayors, in the names of the inhabitants of London, York, Exeter, Yarmouth, Winchester, Honiton, Dover, Southampton, Tiverton, Hertford, the government Malmesbury, Taunton, Marlborough, and other cities and towns. Owing to this or other causes, the king remained firm, and Gibraltar was not surrendered. In 1749, a singular attempt was made in England to advocate such a surrender. A pamphlet appeared under the title, Reasons for Giving up Gibraltar, in which the writer said: I can demonstrate that the use of Gibraltar is only to support and enrich this or that particular man; that it is a great expense to the nation; that the nation is thereby singularly dishonoured, and our trade rather injured, than protected.' It appears that there was gross corruption at that time on the part of the governor and other officials; and that merchants, incensed at the profligate and vexatious management of the port, asserted that trade would be better if the place were in Spanish hands than English-differing so far from a few modern theorists, who have advocated the surrender of Gibraltar on grounds of moral right and fairness towards Spain. There must have been some other agitations, of a similar kind, at that period; for both Houses of parliament addressed George II, praying him not to cede Gibraltar. The 'Key to the Mediterranean,' as it has been well called, was besieged unavailingly by Spain in 1727, and by Spain and France in 1779--since which date no similar attempt has been made. The siege, which was commenced in 1779, and not terminated till 1783, was one of the greatest on record. The grand attack was on the 13th of September 1782. On the land-side were stupendous batteries, mounting 200 pieces of heavy ordnance, supported by a well-appointed army of 40,000 men, under the Duc de Crillon; on the sea-side were the combined fleets of France and Spain, numbering 47 sail of the line, besides numerous frigates and smaller vessels, and 10 battering-ships of formidable strength. General Elliott's garrison threw 5000 red-hot shot on that memorable day; and the attack was utterly defeated at all points. THE FIRST ROAD-TRAMWAYOn the 24th of July 1801, a joint-stock under-taking was completed, which marks an important era in the history of railways. It was the Surrey Iron Railway, from Wandsworth to Croydon, and thence southward in the direction of Merstham. We should regard it as a trifling affair if witnessed now: a train of donkeys or mules drawing small wagons of stone along a very narrow-gauge rail-way but its significance is to be estimated in reference to the things of that day. At the coal-mines in the north of England, the fact had long been recognised, that wheels will roll over smooth iron more easily than over rough gravel or earth; and to take advantage of this circumstance, rails were laid down on the galleries, edits, and staiths. Certain improvements made in these arrangements in 1800 by Mr. Benjamin Outram, led to the roads being termed Outran roads; and this, by an easy abbreviation, was changed to tramroads, a name that has lived ever since. Persons in various parts of England advocated the laying of tram-rails on common roads, or on roads purposely made from town to town; in order that upper-ground traffic might share the benefits already reaped by mining operations. In 1800, Mr. Thomas, of Denton, read a paper before the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, in which this view of the matter was ably advocated. In 1801, Dr. James Anderson, of Edinburgh, in his Recreations of Agriculture, set forth, in very glowing terms, the anticipated value of horse-tramways.' 'Diminish carriage expenses by one farthing,' he said, 'and you widen the circle of intercourse; you form, as it were, a new creation, not only of stones and earth, trees and plants, but of men also, and, what is more, of industry, happiness, and joy.' In a less enthusiastic, and more practical strain, he proceeded to argue that the use of such tramways would lessen distances as measured by time, economise horse-power, lead to the improvement of agriculture, and lower the prices of commodities. The Surrey Iron Railway was not a very successful affair, commercially considered; but this was not due to any failure in the principle of construction adopted. In 1802, Mr. Lovell Edgeworth, father of the eminent writer, Maria Edgeworth, proposed that passengers as well as minerals should be conveyed on such tramways: a suggestion, however, that was many years in advance of public opinion. When, however, it was found that one horse could draw a very heavy load of stone on the Surrey tramway, and that a smooth road was the only magic employed, engineers began to speculate on the vast advantages that must accrue from the use, on similar or better roads, of trains drawn by steam-power instead of horse-power. Hence the wonderful railway-system of our day. The Surrey iron-path has long been obliterated; it was bought up, and removed by the Brighton and Croydon Railway Companies. FLEET MARRIAGESThe Weekly Journal of June 29, 1723, says: 'From an inspection into the several registers for marriages kept at the several alehouses, brandy-shops, &c., within the Rules of the Fleet Prison, we find no less than thirty-two couples joined together from Monday to Thursday last without licenses, contrary to an express act of parliament against clandestine marriages, that lays a severe fine of £200 on the minister so offending, and £100 each on the persons so married in contradiction to the said statute. Several of the above-named brandy-men and victuallers keep clergymen in their houses at 20s. per week, hit or miss; but it is reported that one there will stoop to no such low conditions, but makes, at least, £500 per annum, of divinity-jobs after that manner.'  These marriages, rather unlicensed than clandestine, seem to have originated with the incumbents of Trinity Minories and St. James's, Duke's Place, who claimed to be exempt from the jurisdiction of the bishop of London, and performed marriages without banns or license, till Elliot, rector of St. James, was suspended in 1616, when the trade was taken up by clerical prisoners living within the Rules of the Fleet, and who, having neither cash, character, nor liberty to lose, became the ready instruments of vice, greed, extravagance, and libertinism. Mr. Burn, who has exhausted the subject in his History of Fleet Marriages, enumerates eighty-nine Fleet parsons by name, of whom the most famous were John Gayman or Gainham, known as the 'Bishop of Hell '-a lusty, jolly man, vain of his learning; Edward Ashwell, a thorough rogue and vagabond; Walter Wyatt, whose certificate was rendered in the great case of Saye and Sele; Peter Symson; William Dan; D. Wigmore, convicted for selling spirituous liquors unlawfully; Starkey, who ran away to Scotland to escape examination in a trial for bigamy; and James Lando, one of the last of the tribe. The following are specimens of the style in which these matrimonial hucksters appealed for public patronage: G. R.-At the true chapel, at the old Red Hand and Mitre, three doors up Fleet Lane, and next door to the White Swan, marriages are performed by authority by the Rev. Mr. Symson, educated at the university of Cambridge, and late chaplain to the Earl of Rothes.-N.B. Without imposition.' 'J. Lilley, at ye Hand and Pen, next door to the China-shop, Fleet Bridge, London, will be performed the solemnisation of marriages by a gentleman regularly bred at one of our universities, and lawfully ordained according to the institutions of the Church of England, and is ready to wait on any person in town or country.' 'Marriages with a license, certificate, and crown-stamp, at a guinea, at the New Chapel, next door to the China-shop, near Fleet Bridge, London, by a regular bred clergyman, and not by a Fleet parson, as is insinuated in the public papers; and that the town may be freed mistakes, no clergyman being a prisoner within the Rules of the Fleet, dare marry; and to obviate all doubts, the chapel is not on the verge of the Fleet, but kept by a gentleman who was lately chaplain on board one of his majesty's men-of-war, and likewise has gloriously distinguished himself in defence of his king and country, and is above committing those little mean actions that some men impose on people, being determined to have everything conducted with the utmost decorum and regularity, such as shall always be supported on law and equity.' Some carried on the business at their own lodgings, where the clocks were kept always at the canonical hour; but the majority were employed by the keepers of marriage-houses, who were generally tavern-keepers. The Swan, the Lamb, the Horse-shoe and Magpie, the Bishop-Blaise, the Two Sawyers, the Fighting cocks, the Hand and Pen, were places of this description, as were the Bull and Garter and King's Head, kept by warders of the prison. The parson and landlord. (who usually acted as clerk) divided the fee between them - unless the former received a weekly wage-after paying a shilling to the plyer or tout who brought in the customers. The marriages were entered in a pocket-book by the parson, and after-wards, on payment of a small fee, copied into the regular register of the house, unless the interested parties desired the affair to he kept secret. The manners and customs prevalent in this matrimonial mart are thus described by a correspondent of The Grub Street Journal, in 1735: 'These ministers of wickedness ply about Ludgate Hill, pulling and forcing people to some pedling alehouse or a brandy-shop to be married, even on a Sunday stopping them as they go to church, and almost tearing their clothes off their backs. To confirm the truth of these facts, I will give you a case or two which lately happened. Since mid-summer last, a young lady of birth and fortune was deluded. and forced from her friends, and by the assistance of a wry-necked, swearing parson, married to an atheistical wretch, whose life is a continued practice of all manner of vice and debauchery. And since the ruin of my relative, another lady of my acquaintance had like to have been trepanned in the following manner: This lady had appointed to meet a gentlewoman at the Old Play-house, in Drury Lane; but extraordinary business prevented her coming. Being alone when the play was done, she bade a boy call a coach for the city. One dressed like a gentleman helps her into it, and jumps in after her. 'Madam,' says he, 'this coach was called for me, and since the weather is so bad, and there is no other, I beg leave to bear you company; I am going into the city, and will set you down wherever you please.' The lady begged to be excused, but he bade the coachman drive on. Being come to Ludgate Hill, he told her his sister, who waited his coming but five doors up the court, would go with her in two minutes. He went, and returned with his pre-tended sister, who asked her to step in one minute, and she would wait upon her in the coach. The poor lady foolishly followed her into the house, when instantly the sister vanished, and a tawny fellow, in a black coat and a black wig, appeared. 'Madam, you are come in good time, the doctor was just agoing!' 'The doctor,' says she, horribly flighted, fearing it was a madhouse, 'what has the doctor to do with me?' 'To marry you to that gentleman. The doctor has waited for you these three hours, and will be paid by you or that gentleman before you go!' 'That gentleman,' says she, recovering herself, 'is worthy a better fortune than mine;' and begged hard to be gone. But Doctor Wryneck swore she should be married; or if she would not, he would still have his fee, and register the marriage for that night. The lady, finding she could not escape without money or a pledge, told them she liked the gentleman so well, she would certainly meet him tomorrow night, and gave them a ring as a pledge, ' Which,' says she, 'was my mother's gift on her death-bed, enjoining that, if ever I married, it should be my wedding ring;' by which cunning contrivance she was delivered from the black doctor and his tawny crew. Some time after this, I went with this lady and her brother in a coach to Ludgate Hill in the daytime, to see the manner of their picking up people to be married. As soon as our coach stopped near Fleet Bridge, up conies one of the myrmidons. 'Madam,' says he, 'you want a parson?' 'Who are you?' says I. 'I am the clerk and register of the Fleet.' 'Skew me the chapel.' At which conies a second, desiring me to go along with him. Says he: 'That fellow will carry you to a pedling alehouse.' Says a third: 'Go with me, he will carry you to a brandy-shop.' In the interim conies the doctor. 'Madam,' says he, 'I'll do your job for you presently!' 'Well, gentlemen,' says I, ' since you can't agree, and I can't be married quietly, I'll put it off till another time;' and so drove away.' The truthfulness of this description is attested by Pennant: 'In walking along the street, in my youth, on the side next the prison, I have often been tempted by the question: 'Sir, will you be pleased to walk in and be married?' Along this most lawless space was hung up the frequent sign of a male and female hand enjoined, with Marriages performed within, written beneath. A dirty fellow invited you in. The parson was seen walking before his shop; a squalid profligate figure, clad in a tattered plaid night-gown, with a fiery face, and ready to couple you for a dram of gin or a roll of tobacco.' In 1719, Mrs. Anne Leigh, an heiress, was decoyed from her, friends in Buckinghamshire, married at the Fleet chapel against her consent, and barbarously ill-used by her abductors. In 1737, one Richard Leaver, being tried for bigamy, declared he knew nothing of the woman claiming to be his wife, except that one night he got drunk, and 'next morning found myself abed with ' a strange woman. 'Who are you? how came you here?' says I. 'Oh, my dear,' says she, 'we were married last night at the Fleet!'' These are but two of many instances in which waifs of the church and self-ordained clergymen, picking up a livelihood in the purlieus of the Fleet, aided and abetted nefarious schemers. For a consideration, they not only provided bride or bridegroom, but antedated marriages, and even gave certificates where no marriage took place. In 1821, the government purchased the registers of several of the marriage-houses, and deposited them with the Registrar of the Consistory Court of London; and in these registers we have proofs, under the hands of themselves and their clerks, of the malpractices of the Fleet parsons, as the following extracts will shew: '5 Nov. 1742, was married Benjamin Richards, of the parish of St. Martin's-in-the-Fields, Br. and Judith Lance, Do. sp. at the Bull and Garter, and gave [a guinea] for an antedate to March ye 11th in the same year, which Lilley comply'd with, and put 'em in his book accordingly, there being a vacancy in the book suitable to the time.' June 10, 1729.-John Nelson, of ye parish of St. George, Hanover, batchelor and gardener, and Mary Barnes of ye same, sp. married. Cer. dated 5 November 1727, to please their parents.' 'Mr. Comyngs gave me half-a-guinea to find a bridegroom, and defray all expenses. Parson, 2s. 6d. Husband do., and 5. 6 myself.' [We find one man married four times under different names, receiving five shillings on each occasion 'for his trouble.'] 1742, May 24.-A soldier brought a barber to the Cock, who, I think, said his name was James, barber by trade, was in part married to Elizabeth: they said they were married enough.' 'A coachman came, and was half-married, and would give but 3s. 6d., and went off.' Edward - and Elizabeth - were married, and would not let me know their names.' 'The woman ran across Ludgate Hill in her shift.' [Under the popular delusion that, by so doing, her husband would not be answerable for her debts.] 'April 20, 1742, came a man and woman to the Bull and Garter, the man pretended he would marry ye woman, by w'ch pretence be got moneyto pay for marrying and to buy a ring, but left the woman by herself, and never returned; upon which J. Lilley takes the woman from the Bull and Garter to his own house, and gave her a certifycate, as if she had been married to the man.' '1 Oct. 1747.-John Ferren, gent. ser. of St. Andrew's, Holborn, Br, and Deborah Nolan, do. sp. The supposed J. F. was discovered, after the ceremonies were over, to be in person a woman.' 'To be kept a secret, the lady having a jointure during the time she continued a widow.' Sometimes the parsons met with rough treatment, and were glad to get off by sacrificing their fees. One happy couple stole the clergyman's clothes-brush, and another ran away with the certificate, leaving a pint of wine unpaid for. The following memorandums speak for themselves: 'Had a noise for four hours about the money.' 'Married at a barber's shop one Kerrils, for halfa-guinea, after which it was extorted out of my pocket, and for fear of my life, delivered.' 'The said Harronson swore most bitterly, and was pleased to say that he was fully determined to kill the minister, etc., that married him. N. B.-He came from Gravesend, and was sober!' Upon one occasion the parson, thinking his clients were not what they professed to he, ventured to press some inquiries. He tells the result in a Nota Bene: 'I took upon me to ask what ye gentleman's name was, his age, and likewise the lady's name and age. Answer was made me, G-d- me, if I did not immediately marry them, he would use me ill; in short, apprehending it to be a conspiracy, I found myself obliged to marry them in terrorem.' However, the frightened rascal took his revenge, for he adds in a second N.B., ' some material part was omitted!' Dare's Register contains the following: 'Oct. 2, 1743.-John Figg, of St. John the Evangelist, gent., a widower, and Rebecca Wordwand, of ditto, spinster. At ye same time gave her ye sacrament.' This, however, is the only instance recorded of such blasphemous audacity. The hymeneal market was not supported only by needy fortune-hunters and conscienceless profligates, ladies troubled with duns, and spinsters wanting husbands for reputation's sake. All classes flocked to the Fleet to marry in haste. Its registers contain the names of men of all professions, from the barber to the officer in the Guards, from the pauper to the peer of the realm. Among the aristocratic patrons of its unlicensed chapels we find Edward, Lord Abergavenny; the Hon. John Bourke, afterwards Viscount Mayo; Sir Marmaduke Gresham; Anthony Henley, Esq., brother of Lord Chancellor Northington; Lord Banff; Lord Montagu, afterwards Duke of Manchester; Viscount Sligo; the Marquis of Annandale; William Shipp, Esq., father of the first Lord Mulgrave; and Henry Fox, afterwards Lord Holland, of whose marriage Walpole thus writes to Sir Horace Mann: 'The town has been in a great bustle about a private match; but which, by the ingenuity of the ministry, has been made politics. Mr. Fox fell in love with Lady Caroline Lenox (eldest daughter of the Duke of Richmond), asked her, was refused, and stole her. His father was a footman, her great-grandfather, a king-hinc illae lachrymae! All the blood-royal have been up in arms.' A few foreigners figure in the Fleet records, the most notable entry in which an alien is concerned being this: ' 10 Aug. 1742. -Don Dominian Bonaventura, Baron of Spiterii, Abbott of St. Mary, in Praeto Nobary, chaplain of hon. to the king of the Two Sicilies, and knight of the order of St. Salvator, St. James, and Martha Alexander, ditto, Br. and sp.' Magistrates and parochial authorities helped to swell the gains of the Fleet parsons; the former settling certain cases by sending the accused to the altar instead of the gallows, and the latter getting rid of a female pauper, by giving a gratuity to some poor wretch belonging to another parish to take her for better for worse. From time to time, the legislature attempted to check these marriages; but the infliction of pains and penalties were of no avail so long as the law recognised such unions. At length Chancellor Hardwicke took the matter in hand, and in 1753 a bill was introduced, making the solemnisation of matrimony in any other but a church or chapel, and without banns or license, felony punishable by transportation, and declaring all such marriages null and void. Great was the excitement created; handbills for and against the measure were thrown broadcast into the streets. The bill was strenuously opposed by the opposition, led by Henry Fox and the Duke of Bedford, but eventually passed by a large majority, and became the law of the land from Lady-Day 1754, and so the scandalous matrimonial-market of the Fleet came to an end.'' MINT, SAVOY, AND MAY-FAIR MARRIAGESThe Fleet chapels had competitors in the Mint, May-Fair, and the Savoy. In 1715, an Irishman, named Briand, was fined £2000 for marrying an orphan about thirteen years of age, whom he decoyed into the Mint. The following curious certificate was produced at his trial: 'Feb. 16th, 1715, These are therefore, whom it may concern, that Isaac Briand and Watson Anne Astone were joined together in the holy state of matrimony (Nemine contradicente) the day and year above written, according to the rites and ceremonies of the church of Great Britain. Witness my hand, Jos. Smith, Cler: In 1730, a chapel was built in May Fair, into which the Rev. Alexander Keith was inducted. He advertised in the public papers, and carried on a flourishing trade till 1742, when he was prosecuted by Dr. Trebeck, and excommunicated. In return, he excommunicated the doctor, the bishop of London, and the judge of the Ecclesiastical Court. The following year, he was committed to the Fleet Prison; but he had a house opposite his old chapel fitted up, and carried on the business through the agency of curates. At this chapel, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's worthless son was married; and here the impatient Duke of Hamilton was wedded with a ring from a bed-curtain, to the youngest of the beautiful Gunnings, at half-past twelve at night. When the marriage act was mooted, Keith swore that he would revenge him-self upon the bishops, by taking some acres of land for a burying-ground, and underburying them all. He published a pamphlet against the measure, in which he states it was a common thing to marry from 200 to 300 sailors when the fleet came in, and consoles himself with the reflection, that if the alteration in the law should prove beneficial to the country, he will have the satisfaction of having been the cause of it, the compilers of the act having done it 'with the pure design' of suppressing his chapel. No less than sixty-one couples were united at Keith's chapel the day before the act came into operation. He himself died in prison in 1758. The Savoy Chapel did not come into vogue till after the passing of the marriage bill. On the 2nd January 1754, the Public Advertiser contained this advertisement: ' By Authority.-Marriages performed with the utmost privacy, decency, and regularity at the Ancient Royal Chapel of St. John the Baptist, in the Savoy, where regular and authentic registers have been kept from the time of the Reformation (being two hundred years and upwards) to this day. The expense not more than one guinea, the five-shilling stamp included. There are five private ways by land to this chapel, and two by water.' The proprietor of this chapel was the Rev. John Wilkinson (father of Tate Wilkinson, of theatrical fame), who fancying (as the Savoy was extra-parochial) that he was privileged to issue licenses upon his own authority, took no notice of the new law. In 1755, he married no less than 1190 couples. The authorities began at last to bestir themselves, and Wilkinson thought it prudent to conceal himself. He engaged a curate, named Grierson, to perform the ceremony, the licenses being still issued by himself, by which arrangement he thought to hold his assistant harm-less. Among those united by the latter, were two members of the Drury Lane company. Garrick, obtaining the certificate, made such use of it that Grierson was arrested, tried, convicted, and sentenced to fourteen years' transportation, by which sentence 1400 marriages were declared void. In 1756, Wilkinson, making sure of acquittal, surrendered himself; and received the same sentence as Grierson, but died on board the convict-ship as she lay in Plymouth harbour, whither she had been driven by stress of weather. |