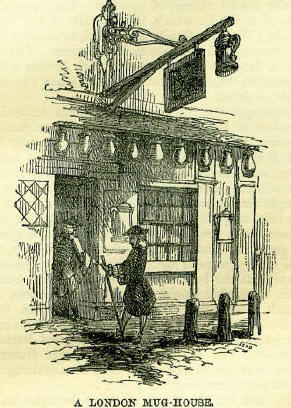

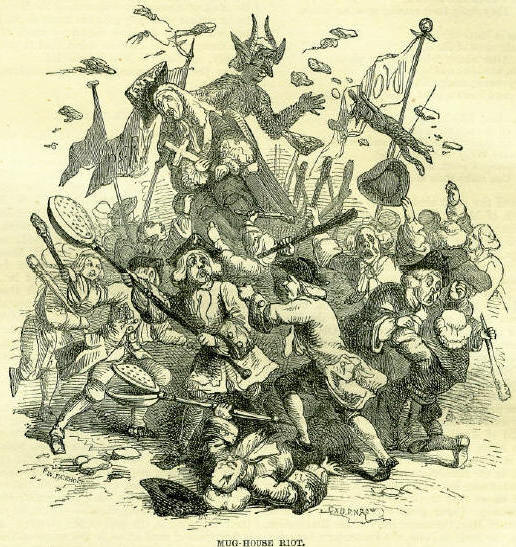

23rd JulyBorn: Godfrey Olearius, the younger, German divine, 1672, Leipsic. Died: St. Bridget of Sweden, 1373; Sir Robert Sherley, English military adventurer in Persia, 1627; Richard Gibson, artist, 1690; Gilles Menage, grammarian and versifier, 1692, Paris; Vicomte Alexandre de Beauharnais, first husband of the Empress Josephine, guillotined, 1794; Jean Francois Vauvilliers, eminent French scholar, 1800, St. Petersburg; Arthur Wolfe, Lord Kilwarden, murdered by the populace in Dublin, 1803; Mrs. Elizabeth Hamilton, authoress of the Cottagers of Glenburnie, 1816, Harrowgate. Feast Day: St. Apollinaris, bishop of Ravenua, martyr, 1st century. St. Liborius, bishop of Mans, confessor, about 397. ST. BRIDGET OF SWEDENBirgir, widow of Ulpho, Prince of Nericia, died on the 23rd of July 1372, and, a few years after-wards, was canonised by Pope Boniface IX, under the appellation of St. Bridget of Sweden. Unlike most other saints, there seems to have been little more miraculous in her character and career, than the simple fact, that she was a pious woman, a scholar, and writer on religious subjects, at a period of general barbarism. She founded the monastic order of Bridgetines, peculiar of its kind, as it included both nuns and monks under the same roof. The regular establishment of a house of Bridgetines munbered sixty nuns, thirteen monks, four deacons, and eight lay-brothers; the lady-abbess controlling and superintending the whole. The mortified. and religious life to which they had bound themselves, by the most solemn engagements, was supposed to render the mixed inmates of these convents superior to temptation, and free from the slightest suspicion of evil. Strange stories, nevertheless, have been told of these communities, and the greater part, if not all, of the convents of the order that now exist, are of one sex alone. There is an ancient wood-cut, formerly in the possession of Earl Spencer, representing St. Bridget of Sweden writing her works. A pilgrim's staff, hat, and scrip, raised behind her, alluded to her many pilgrimages. The letters S.P.Q.R., in the upper corner, denoted that she died at Rome. The lion of Sweden, and crown at her feet, shewed that she was a princess of that country, as well as her contempt for worldly dignities. A legend above her head consisted of a brief invocation in German: ' 0, Brigita, bit Got fur uns!'-0, Bridget, pray to God for us! A striking illustration of the inherent vitality of extreme weakness, not unfrequently met with, both in the moral and physical world, is exhibited in the history of the first and only house of Bridgetines established in England. About 1420, Henry V., as a memorial of the battle of Agincourt, founded the Bridgetine House of Sion, on that pleasant bank of the Thames, now so well known by the palatial residence of the Duke of Northumberland. And there, with broad lands, fisheries, mill-sites, water-courses, and other valuable endowments, the establishment-the female part consisting principally of ladies of rank-flourished in peace and plenty till the dissolution of monasteries in 1539. Even then the inmates were not thrown helpless on the world; all were allowed pensions, more or less according to their stations, from Dame Agnes Jordan, the abbess, who received £200 per annum, for life, down to the humble lay-brother, whose yearly dole was £2, 13s. 4d. The community thus broken up, did not all separate. A few holding together, joined a convent of their order at Dermond, in Flanders; from whence they were brought back, and triumphantly reinstated in their original residence of Sion, by Queen Mary, in 1557. Of those who had remained in England at the dissolution, few were found, after a lapse of eighteen years, to join their old community. Some were dead; some, renouncing their ancient faith, or yielding to the dictates of nature, had married. As old Fuller quaintly phrases it, 'the elder nuns were in their graves, the younger in the arms of their husbands;' but with the addition of new members, the proper number was again made up. But scarcely had they been settled in their ancient abode, ere the accession of Elizabeth once more dissolved the establishment; and at this second dissolution, all the nuns, with the exception of the abbess, left England, to seek a place of rest and refuge at Dermond. The convent at Dermond being too poor to support so many, the Duchess of Parma gave the English nuns a monastery in Zealand, to which they transferred the House of Sion; but the place being unendorsed and unhealthy; poverty and sickness compelled them to abandon it, and they were fortunate enough to obtain a house and church near Antwerp. Here the fugitives thought they had at last found a shelter and a home, but they soon were discovered. In a popular tumult, their house and furniture were destroyed, and only by a timely flight did they themselves escape insult and injury from the rudest of the populace. Their next establishment was at Mechlin, where they lived for seven years, till that city was taken by the Prince of Orange. In the misery and confusion consequent thereon, the nuns were accidentally discovered by some English officers in the service of the prince, who preserved and protected them; and learning that they might find a shelter at Rouen, the officers, though of the reformed faith, protected their countrywomen in all honour and safety to Antwerp, and provided them with a passage to France. Arriving at Rouen in 1589, the sisters of Sion, though sunk in poverty, had another brief rest, till that city was besieged by Henry IV. At its capture, their house was confiscated, but they were assisted to hire a ship to convey them to Lisbon. They arrived at Lisbon in 1594, and were well received; soon finding themselves comfortably situated, with a pension from the king of Spain, a church, monastery, and other endowments. With the exception of being burned out in 1651, and the demolition of their convent by the great earth-quake in 1755, the nuns of Sion, continually recruited by accessions from the British Islands, lived at Lisbon, in peaceful and easy circumstances, till the revolutionary wars of 1809. In that year, ten of then fled for refuge to England; and receiving a small pension from government, managed to subsist, through various vicissitudes and changes of residence, till finally dispersed by death and other causes. But those who remained at Lisbon, after suffering great privations-their convent being made an hospital for the Duke of Wellington's army-recovered all their former privileges at the end of the war; and being joined by several English ladies, became a flourishing community. The last scene of this eventful history is not the least strange, nor can it be better or more concisely told, than in the following paragraph from a London newspaper, published in September 1861: NUNS PER LISBON STEADIER.-The Sultan, on Saturday, brought over twelve nuns of the ancient convent of Sion House, who return to England, having purchased an establishment at Spetisbury, in Dorsetshire. The sisters bring with them the antique stone cross which formerly stood over the gateway of Sion House at Isleworth, also several ancient statues which adorned the original church, and a portrait of Henry V. of England, their founder, which is said to be a likeness, and to have been painted during the monarch's lifetime. This order of Bridgetines has been settled at Lisbon since the year 1595; but there being now more religious liberty in England than in Portugal, and more prospects here for the prosperity of the order, the sisterhood have determined to return to their native land. The Duke of Northumberland, to whose ancestors the ancient Sion House, with its lands, was granted by Henry VIII, has given the poor nuns a handsome donation to assist them in defraying the expenses of their journey and change of establishment.' SIR ROBERT SHERLEYAmong the remarkable travellers of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, not the least so was the youngest son of Sir Thomas Sherley, of Wistenston, in Sussex. A love of adventure seems to have inspired both himself and his elder brother, Sir Anthony, from an early age; for who in those days could fail to be roused when the discoveries of Columbus, Sir Walter Raleigh, and other adventurous seamen were the daily topic? As soon as Robert Sherley was of sufficient age he set off on his travels, and wishing to understand the politics of various European courts, he attached himself to their sovereigns, and, for five years, was employed by them in various missions. The Emperor Bedell, of Germany, was so much satisfied by the talents he evinced on one of his embassies, that he created him a count of the empire. His brother Anthony had, daring this time, been in Persia, and thither Robert followed him, and was introduced at the court. The king, acknowledging the abilities of the stranger who had arrived, made him a general of artillery, and for ten years he fought against the Turks with distinguished bravery; bringing the newest improvements in cannon and arms generally under the notice of the government; but, at the same time, getting into considerable trouble through the envy of the Persian nobles, who could not bear to see honours showered upon a stranger. A life in the east cannot be passed without romance, and so it fell out that the valour and noble conduct of Sir Robert inflamed the hearts of many a fair Persian, but above all of Teresia, the daughter of Ismay Hawn, prince of the city of Hercassia Major, whose sister was one of the queens of Persia. Much difficulty and opposition did the true lovers meet with, but at length they were married. After this, Sir Robert seems to have left the army, and returned to his former life as ambassador to various countries; among the rest, to Rome, where he went in 1609, and was received with every mark of distinction, magnificent entertainments being given to him. He then came to England, bringing his wife with him, who must have been much astonished with the manners of a country which probably none of her countrywomen had ever seen before. They were, however, received with great favour by James, and especially by Henry, Prince of Wales, a young man always ready to welcome enterprising countrymen. Here his wife presented him with a son on the 4th of November 1611, on which occasion the happy father wrote the following letter to the prince, requesting him to stand godfather: 'MOST RENOWNEDE PRINCE-The great hounors and favors it bath pleased your Highnes to use towards me, hathe embouldede me to wrighte thes fewe lyns, which shal he to beseeche your Highnes to Christen a sonn which God bath geven me. Your Highnes in this shal make your servant happy, whose whole loudginge is to doe your Highnes some segniolated servis worthy to be esteemed in your Prinsly breast. I have not the pen of Sissero [Cicero], yet want I not menes to sownde your Highnesse's worthy prayses into the ears of forran nattions and mighty princes; and I assure myselfe your high-borne sperrit thirstes after Fame, the period of great princes' ambissiones. And further I will ever be your Highnes' most humbele and observaunt servant, ROBERT SHERLEY.' This letter certainly does not give us a very high opinion of the ambassador's learning. He was said to be 'a famous general, but a wretched scholar; his patience was more philosophical than his intellect, having small acquaintance with the muses. Many cities he saw, many hills climbed over, and tasted many waters; yet Athens, Parnassus, Hippocrene, were strangers to him: his notion prompted him to other employments.' Yet in spite of this, the prince gave his godchild his own name, the queen taking the office of god-mother; and when the father returned to Persia, he left his little boy under her care. Sherley was again in England in 1624, but with very sad results. A quarrel arose between him and the Persian ambassador, which caused the king to send them both back to Persia, to reconcile their differences. Whether the ambassador felt himself in the wrong, and durst not face his master, certain it is that he poisoned himself on the way; and Sir Robert being unable to gain a hearing and proper satisfaction from the court, died of a broken heart at the age of sixty-three. There is a portrait of him at Petworth, in his Persian dress; for it seems that he liked to appear in England in these foreign garments, as more graceful and picturesque than his national garb. GILLES MENAGEMenage, in the earlier part of his life, was a lawyer, but though, eminently successful as a pleader, he entered the church to acquire more leisure for his favourite pursuit of literature. A curious trial, on which he was engaged, affords a remarkable instance of justice overtaking a criminal, in what maybe termed an unjust manner. A country priest, of a notoriously violent and vicious character, had a dispute about money-matters with the tax-collector of the district; who soon afterwards disappearing, a strong suspicion arose that he had been murdered by the priest. About the same time, a man was executed for highway robbery, and his body gibbeted in chains by the roadside, as a warning to others. The relations of the highwayman came one night and took the body down, with the intention of burying it; but, being frightened by a passing patrol, they could do no more than sink it in a pond, not far from the priest's residence. Some fishermen, when drawing their nets, found the body, and the neighbours applying their previous suspicions to the then much disfigured body of the highwayman, alleged that it was that of the tax-collector. The priest was arrested, tried, and condemned, solemnly protesting against the injustice of his sentence, but, when the day of execution arrived, he admitted that he had perpetrated the crime for which he was about to suffer. Nevertheless, he said, I am unjustly condemned, for the tax-collector's body, with that of his dog, still lies buried in my garden, where I killed them both. On search being made, the bodies of the man and dog were found in the place described by the priest; and subsequent inquiries brought to light the secret of the body found in the pond. RICHARD GIBSON On the 23rd of July 1690, died Richard Gibson, aged seventy-five; and nineteen years afterwards, his widow died at the advanced age of eighty-nine. Nature thus, by length of years, compensated this compendious couple, as Evelyn terms them, for shortness of stature-the united heights of the two amounting to no more than seven feet. Gibson was miniature-painter, in every sense of the phrase, as well as court-dwarf, to Charles I; his wife, Ann Shepherd, was court-dwarf to Queen Henrietta Maria. Her majesty encouraged a marriage between these two clever but diminutive persons; the king giving away the bride, the queen presenting her with a diamond ring; while Waller, the court-poet, celebrated the nuptials in one of his prettiest poems. Design or chance make others wive, But nature did this match contrive; Eve might as well have Adam fled, As she denied her little bed To him, for whom Heaven seemed to frame And measure out this little dame. The conclusion of the poem is very elegant. Ah Chloris! that kind nature, thus, From all the world had severed us; Creating for ourselves, us two, As Love has me, for only you. The marriage was an eminently happy one. The little couple had nine children, five of whom lived to years of maturity, and full ordinary stature. Gibson had the honour of being drawing-master to Queen Mary and her sister Queen Anne. His works were much valued, and one of them was the innocent cause of a tragical event. This painting, representing the parable of the lost sheep, was highly prized by Charles I, who gave it into the charge of Vandervort, the keeper of the royal pictures, with strict orders to take the greatest care of it. In obedience to these orders, the unfortunate man put the picture away so carefully, that he could not find it himself when the king asked for it a short time afterwards. Afraid or ashamed to say that he had mislaid it, Vandervort committed suicide by hanging. A few days after his death, the picture was found in the spot where he had placed it. The courts of the Sultan and Czar are, we believe, the only European ones where dwarfs are still retained as fitting adjuncts to imperial state. The last court-dwarf in England was a German, named Coppernin, retained by the Princess of Wales, mother to George III. CHRISTOBELLA, VISCOUNTESS SAY AND SELEThis lady, who died on 23rd of July 1789, in the ninety-fifth year of her age, was remarkable for her vivacity and sprightliness, even to extreme old age. She was the eldest daughter and coheir of Sir Thomas Tyrrell, Bart. of Castlethorpe, Bucks. She was thrice married: first, to John Knapp, Esq., of Cumner, Berkshire; secondly, to John Pigott, Esq., of Doddershall House, in the parish of Quainton, Bucks; and lastly, to Richard Fiennes, Viscount Say and Sele. Mr. Pigott, her second husband, left her, in dowry for life, his family estates, and Dodder-shall House became her ordinary place of residence. It is a fine old mansion, built in 1639, in the Elizbethan style, and contains some spacious rooms, with much curious and interesting carvings, and antique furniture. Here it was that, after the death of her third husband, when she was at least eighty-six years old, she used frequently to entertain large social parties, and her balls were the gayest and pleasantest in the county. She was the life of all her parties; she still loved the company of the young, and often seemed the sprightliest among them; she was still passionately devoted to dancing, and practised it with grace and elegance, even when many far her juniors, were sinking into the decrepitude of age. Gray, wishing to have a fling at Sir Christopher Hatton's late love of gaiety, sings: Full oft within these spacious walls, When he had fifty winters o'er him, My grave lord-keeper led the brawls, The seals and maces danced before him. But men of fifty were mere boys to Lady Say and Sole, when she gaily tripped it 'on the light fantastic toe,' in her own ball-room at Doddershall. It was truly delicious to see her ladyship at eighty-eight, and her youthful partner of sixty-five, merrily leading the country-dance, or bounding away in the cotillon, or gracefully figuring a fashionable minuet. And around, and around, and around they go, Heel to heel, and toe to toe, Prance and caper, curvet and wheel, Toe to toe, and heel to heel. 'Tis merry, 'tis merry, Sir Giles, I trow, To dance thus at sixty, as we do now. When her ladyship was about ninety, she used to say, that she 'had chosen her first husband for love, her second for riches, and her third for rank, and that she had now some thoughts of beginning again in the same order.' 'I have always hitherto,' she continued, 'been able to secure the best dancer in the neighbourhood for my partner, by sending him an annual present of a haunch or two of venison; but latterly, I begin to think he has shewn a preference for younger ladies; so, I sup-pose, I must increase my bribe, and send him a whole buck at a time, instead of a haunch.' Her exact age was not known, for she most carefully concealed it, and it is said, even caused the record of her baptism to be erased from the parish-register She was buried in the church at Grendon-Underwood, the burial-place of the Pigott family, and the inscription on her monument describes her as ninety-four, but it was generally believed that she was above a hundred when she died. There is a portrait of her at Doddershall, and Pope, who visited her in the time of her second husband, is said to have written some verses in her praise with a diamond on the pane of a window, which unfortunately has been destroyed. Addison, who also visited at Doddershall, is sup-posed to have taken it as his model for an old manor-house. It is only an act of justice to Lady Say and Sele to mention, that while she loved gay recreations, she was not unmindful of the wants of the poor. She was benevolent while living, and in her will, dated two years before her death, she bequeathed large sums of money for the endowment of some excellent charities for the poor of the several parishes with which she was connected. THE CASTING OF THE STOOLSThe 23rd of July 1637 is the date of an event of a semi-ludicrous character, which may be considered as the opening of the civil war. By a series of adroit measures, Junes I contrived to introduce bishops into the Scotch church. His son, Charles I, who was altogether a less dexterous, as well as a more arbitrary ruler, wished to complete the change by bringing in a book of canons and a liturgy. He was backed up by his great councillor Archbishop Laud, whose tendencies were to something like Romanising even the English church. Between them, a service-book, on the basis of the English one, but said to include a few Romish peculiarities besides, was prepared in 1636 for the Scotch church, which was thought to be too much under awe of the royal power to make any resistance. In reality, while a certain deference had been paid to the king's will in religious matters, there was a large amount of discontent in the minds of both clergy and people. The Scotch had all along, from the Reformation, had a strong predilection for evangelical doctrines and a simple and informal style of worship. Bishops ruling in the church-courts they had, with more or less unwillingness, submitted to; but an interference with their ordinary Sunday-worship in the churches was too much for their patience. The king was ill-informed on the subject, or he would never have committed himself to such a dangerous innovation.  On the day mentioned, being Sunday, the service-book was, by an imperious command from the king, to be read in every parish-church in Scotland. Before the day arrived, the symptoms of popular opposition appeared almost everywhere so ominous, that few of the clergy were prepared to obey the order. In the principal church of Edinburgh, the chancel of the old cathedral of St. Giles, which contained the seats of the judges, magistrates, and other authorities, the liturgy was formally introduced under the auspices of the bishop, dean, and other clergy. Here, if any where, it might have been expected that the royal will would have been implicitly carried out. And so it would, perhaps, if there had been only a congregation of official dignitaries. But the body of the church was, in reality, filled by a body of the common sort of people, including a large proportion of citizens' wives and their maid-servants-Christians of vast zeal, and comparatively safe by their sex and their obscurity. There were no pews in those days; each godly dame sat on her own chair or clasp-stool, brought to church on purpose. When the dean, Mr. James Hannay, opened the service-book and began to read the prayers, this multitude was struck with a horror which defied all control. They raised their voices in discordant clamours and abusive language, denouncing the dean as of the progeny of the devil, and the bishop as a belly-god, calling out that it was rank popery they were bringing in. A strenuous female (Jenny Geddes) threw her stool at the dean's head, and whole sackfuls of small clasp-Bibles followed. The bishop from the pulpit endeavoured to calm the people, but in vain. A similar 'ticket of remembrance' to that aimed at the dean was levelled at him, but fell short of its object. The magistrates from their gallery made efforts to quell the disturbance-all in vain; and they were obliged to clear out the multitude by main force, before the reading of the liturgy could be proceeded with. After the formal dismissal of the congregation, the bishop was mobbed on the street, and narrowly escaped with his life. It became apparent to the authorities that they could not safely carry out the royal instructions, and they wrote to court in great anxiety, shewing in what difficulties they were placed. Had the king tacitly withdrawn the service-book, the episcopal arrangements might have held their ground. He pressed on; a formal opposition from the people of Scotland arose, and never rested till the whole policy of the last forty years had been undone. In short, the civil war, which ended in the destruction of the royal government twelve years after, might be said to have begun with the Casting of the Stools in St. Giles's Kirk. LONDON MUG-HOUSES AND THE MUG-HOUSE RIOTSOn the 23rd of July 1716, a tavern in Salisbury Court, Fleet Street, was assailed by a great mob, evidently animated by a deadly purpose. The house was defended, and bloodshed took place before quiet was restored. This affair was a result of the recent change of dynasty. The tavern was one of a set in which the friends of the newly acceded Hanover family assembled, to express their sentiments and organise their measures. The mob was a Jacobite mob, to which such houses were a ground of offence. But we must trace the affair more in detail.  Amongst the various clubs which existed in London at the commencement of the eighteenth century, there was not one in greater favour than the Mug-house Club, which met in a great hall in Long Acre, every Wednesday and Saturday, during the winter. The house had got its name from the simple circumstance, that each member drank his ale (the only liquor used) out of a separate mug. There was a president, who is described in 1722 as a grave old gentleman in his own gray hairs, now full ninety years of age.' A harper sat occasionally playing at the bottom of the room. From time to time, a member would give a song. Healths were drunk, and jokes transmitted along the table. Miscellaneous as the company was-and it included barristers as well as trades-people-great harmony prevailed. In the early days of this fraternity there was no room for politics, or anything that could sour conversation. By and by, the death of Anne brought on the Hanover succession. The Tories had then so much the better of the other party, that they gained the mob on all public occasions to their side. It became necessary for King George's friends to do something in counteraction of this tendency. No better expedient occurred to them, than the establishing of mug-houses, like that of Long Acre, throughout the metropolis, wherein the friends of the Protestant succession might rally against the partizans of a popish pretender. First, they had one in St. John's Lane, chiefly under the patronage of a Mr. Blenman, a member of the Middle Temple, who took for his motto, 'Pro rege et loge;' then arose the Roebuck mug-house in Cheapside, the haunt of a fraternity of young men who had been organised for political action before the end of the late reign. According to a pamphlet on the subject, dated in 1717, 'The next mug-houses opened in the city were at Mrs. Read's coffee-house in Salisbury Court, in Fleet Street, and at the Harp in Tower Street, and another at the Roebuck in Whitechapel. About the same time, several other mug-houses were erected in the suburbs, for the reception and entertainment of the like loyal societies; viz., one at the Ship, in Tavistock Street, Covent Garden, which is mostly frequented by loyal officers of the army; another at the Black Horse, in Queen Street, near Lincoln's-Inn-Fields, set up and carried on by gentlemen, servants to that noble patron of loyalty, to whom this vindication of it is inscribed [the Duke of Newcastle]; a third was set up at the Nag's Head, in James's Street, Covent Garden; a fourth at the Fleece, in Burleigh Street, near Exeter Exchange; a fifth at the Hand and Tench, near the Seven Dials; several in Spittlefields, by the French refugees; one in Southwark Park; and another in the Artillery Ground.' Another of the rather celebrated mud houses was the Magpie, without Newgate, which still exists in the Magpie and Stump, in the Old Bailey. At all of these houses it was customary in the forenoon to exhibit the whole of the mugs belonging to the establishment in a range over the door-the best sign and attraction for the loyal that could have been adopted, for the White Horse of Hanover itself was not more emblematic of the new dynasty than was-the Mug. It was the especial age of clubs, and the frequenters of these mug-houses formed themselves into societies, or clubs, known generally as the Mug-house Clubs, and severally by some distinctive name or other, and each club had its president to rule its meetings and keep order. The president was treated with great ceremony and respect: he was conducted to his chair every evening at about seven o'clock, or between that and eight, by members carrying candles before and behind him, and accompanied with music. Having taken a seat, he appointed a vice-president, and drank the health of the company assembled, a compliment which the company returned. The evening was then passed in drinking successively loyal and other healths, and in singing songs. Soon after ten, they broke up, the president naming his successor for the next evening, and, before he left the chair, a collection was made for the musicians. These clubs played a very active part in the violent political struggles of the time. The Jacobites had laboured with much zeal to secure the alliance of the street-mob, and they had used it with great effect, in connection with Dr. Sacheverell, in over-throwing Queen Anne's Whig government, and paving the way for the return of the exiled family. Disappointment at the accession of George I rendered the party of the Pretender more unscrupulous, the mob was excited to go to greater lengths, and the streets of London were occupied by an infuriated rabble, and presented nightly a scene of riot such as can hardly be imagined in our quiet times. It was under these circumstances that the mug-house clubs volunteered, in a very disorderly manner, to be the champions of order, and with this purpose it became a part of their evening's entertainment to march into the street and fight the Jacobite mob. This practice commenced in the autumn of 1715, when the club called the Loyal Society, which met at the Roebuck, in Cheapside, distinguished itself by its hostility to Jacobitism. On one occasion, at the period of which we are now speaking, the members of this society, or the Mug-house Club of the Roebuck, had burned the Pretender in effigy. Their first conflict with the mob recorded in the newspapers occurred on the 31st of October 1715. It was the birthday of the Prince of Wales, and was celebrated by illuminations and bonfires. There were a few Jacobite alehouses, chiefly situated on Holborn Hill [Sacheverell's parish], and in Ludgate Street; and it was probably the frequenters of the Jacobite public-house in the latter locality who stirred up the mob on this occasion to raise a riot on Ludgate Hill, put out the bonfire there, and break the windows which were illuminated. The Loyal Society men, receiving intelligence of what was going on, hurried to the spot, and, in the words of the newspaper report, 'soundly thrashed and dispersed' the rioters. The 4th of November was the anniversary of the birth of King William III, and the Jacobite mob made a large bonfire in the Old Jury, to burn an effigy of that monarch; but the mug-house men came upon them again, gave them 'due chastisement with oaken plants,' demolished their bonfire, and carried King William in triumph to the Roebuck. Next day was the commemoration of gunpowder treason, and the loyal mob had its pageant. A long procession was formed, having in front a figure of the infant Pretender, accompanied by two men bearing each a warmin pan, in allusion to the story about his birth, and followed by effigies, in gross caricature, of the pope, the Pretender, the Duke of Ormond, Lord Bolingbroke, and the Earl of Marr, with halters round their necks, and all of which were to be burned in a large bonfire made in Cheapside. The procession, starting from the Roebuck, went through Newgate Street, and up Holborn Hill, where they compelled the bells of St. Andrew's Church, of which Sacheverell was incumbent, to ring; thence through Lincoln's-Inn-Fields and Covent Garden to the gate of St. James's palace; returning by way of Pall-Mall and the Strand, and through St. Paul's Churchyard. They had met with no interruption on their way, but on their return to Cheapside, they found that, during their absence, that quarter had been invaded by the Jacobite mob, who had carried away all the materials which had been collected for the bonfire. Thus the various anniversaries became, by such demonstrations, the occasions for the greatest turbulence; and these riots became more alarming, in consequence of the efforts which were made to increase the force of the Jacobite mob. On the 17th of November, of the year just mentioned, the Loyal Society met at the Roebuck, to celebrate the anniversary of the accession of Queen Elizabeth; and, while busy with their mugs, they received information that the Jacobites, or, as they commonly called them, the Jacks, were assembled in great force in St. Martin's-le-Grand, and preparing to burn the effigies of King William and King George, along with the Duke of Marlborough. They were so near, in fact, that their party-shouts of High Church, Ormond, and King James, must have been audible at the Roebuck, which stood opposite Bow Church. The 'Jacks' were starting on. their procession, when they were overtaken in Newgate Street by the mug-house men from the Roebuck, and a desperate encounter took place, in which the Jacobites were defeated, and many of them were seriously injured. Meanwhile the Roebuck itself had been the scene of a much more serious tumult. During the absence of the great mass of the members of the club, another body of Jacobites, much more numerous than those engaged in Newgate Street, suddenly assembled and attacked the Roebuck mug-house, broke its windows and those of the adjoining houses, and with terrible threats, attempted to force the door. One of the few members of the Loyal Society who remained at home, discharged a gun upon those of the assailants who were attacking the door, and killed one of their leaders. This, and the approach of the lord mayor and city officers, caused the mob to disperse; but the Roebuck was exposed to continued attacks during several following nights, after which the mobs remained tolerably quiet through the winter.  With the month of February 1716, these riots began to be renewed with greater violence than over, and large preparations were made for an active mob-campaign in the spring. The mug - houses were refitted, and re-opened with ceremonious entertainments, and new songs were composed to encourage and animate the clubs. Collections of these mug-house songs were printed in little volumes, of which copies are still preserved, though they now come under the class of rare books. The Jacobite mob was again heard gathering in the streets by its well-known signal of the beating of marrow-bones and cleavers, and both sides were well furnished with staves of oak, their usual arms, for the combat, although other weapons, and missiles of various descriptions, were in common use. One of the mum house songs gives the following account of the way in which these riots were carried on: Since the Tories could not fight, And their master took his flight, They labour to keep up their faction; With a bough and a stick, And a stone and a brick, They equip their roaring crew for action. Thus in battle-array, At the close of the day, After wisely debating their plot, Upon windows and stall They courageously fall, And boast a great victory they've got. But, alas! silly boys! For all the mighty noise Of their 'High Church and Ormond for ever!' A brave Whig, with one hand, At George's command, Can make their mightiest hero to quiver. One of the great anniversaries of the Whigs was the 8th of March, the day of the death of King William; and with this the more serious mug-house riots of the year 1716 appear to have commenced. A large Jacobite mob assembled to their old watch-word, and marched along Cheapside to attack the Roebuck; but they were soon driven away by a small party of the Loyal Society, who met there. The latter then marched in procession through Newgate Street, paid their respects to the Magpie as they passed, and went through the Old Bailey to Ludgate Hill. On their return, they found that the Jacobite mob had collected in great force in their rear, and a much more serious engagement took place in Newgate Street, in which the 'Jacks' were again beaten, and many persons sustained serious personal injury. Another great tumult, or rather series of tumults, occurred on the evening of the 23rd of April, the anniversary of the birth of Queen Anne, during which there were great battles both in Cheapside and at the end of Giltspur Street, in the immediate neighbourhood of the two celebrated snug-houses, the Roebuck and the Magpie, which shows that the Jacobites had now become enterprising. Other great tumults took place on the 29th of May, the anniversary of the Restoration, and on the 10th of June, the Pretender's birthday. From this time the Roebuck is rarely mentioned, and the attacks of the mob appear to have been directed against other houses. On the 12th of July, the mug-house in Southwark, and, on the 20th, that in Salisbury Court (Read's Coffee-house), were fiercely assailed, but successfully defended. The latter was attacked by a much more numerous mob on the evening of the 23rd of July, and after a resistance which lasted all night, the assailants forced their way in, and kept the Loyal Society imprisoned in the upper rooms of the house while they gutted the lower part, drank as much ale out of the cellar as they could, and let the rest run out. Read, in desperation, had shot their ringleader with a blunderbuss, in revenge for which they left the coffeehouse-keeper for dead; and they were at last with difficulty dispersed by the arrival of the military. The inquest on the dead man found a verdict of wilful murder against Read; but, when put upon his trial, he was acquitted, while several of the rioters, who had been taken, were hanged. This result appears to have damped the courage of the rioters, and to have alarmed all parties, and we hear no more of the mug-house riots. Their incompatibility with the preservation of public order was very generally felt, and they became the subject of great complaints. A few months later, a pamphlet appeared, under the title of Down with the Mug, or Reasons for Suppressing the Mug-houses, by an author who only gave his name as Sir H. M.; but who seems to have shown so much of what was thought to be Jacobite spirit, that it provoked a reply, entitled The Mug Vindicated. But the mug-houses, left to themselves, soon became very harmless. BLOOMER COSTUMEThe originator of this style of dress was Mrs. Amelia Bloomer, the editor of a temperance journal named The Lily, which was published at Seneca Falls, New York. A portrait of her, exemplifying her favourite costume, is given on the following page, from a photograph taken by Mr. T. W. Brown, Auburn, New York. The dress was first brought practically before the notice of the world, at a ball held on the 23rd of July 1851, at the cotton-manufacturing town of Lowell, Massachusetts. It was an attempt to substitute for the cumbrous, inconvenient, inelegant, and in many other respects objectionable dress which then and has since prevailed, one of a light, graceful, and convenient character. In no part of the world, perhaps, would such a reform have been attempted but in one where women had for some time been endeavouring to assert an. individuality and independence heretofore unknown to the meeker sex. But, like many other reformers, Mrs. Bloomer lived before her proper day. In the pleading which she made for the proposed change in her magazine, she defended it from the charge of being either immodest or inelegant. She there adverts to the picturesque dress of the Polish ladies, with high fur-trimmed boots, and short tunic skirt: and she asks: 'If delicacy requires that the skirt should be long, why do our ladies, a dozen times a day, commit the indelicacy of raising their dresses, which have already been sweeping the side-walks, to prevent their draggling in the mud of the streets? Surely a few spots of mud added to the refuse of the side-walks, on the hem of their garment, are not to be compared to the charge of indelicacy, to which the display they make might subject them!' It may here be mentioned, in illustration of this matter, that the streets of American cities are kept much less carefully cleaned than those of our British cities. The authorities in the new fashion left the upper portion of the dress to be determined according to the individual taste of the wearer; but Mrs. Bloomer described the essential portion as follows: 'We would have a skirt reaching down to nearly half-way between the knee and the ankle, and not made quite so full as is the present fashion. Underneath this skirt, trousers moderately full, in fair, mild weather, coming down to the ankle (not instep), and there gathered in with an elastic band, The shoes or slippers to suit the occasion. For winter, or wet weather, the trousers also full, but coming down into a boot, which should rise some three or four inches at least above the ankle. This boot should be gracefully sloped at the upper edge, and trimmed with fur, or fancifully embroidered, according to the taste of the wearer. The material might be cloth, morocco, moose-skin, &c., and water-proof, if desirable.'  The costume-reformer adduced many advantages which would follow the use of this kind of dress. There would be less soiling from the muddy state of the streets; it would be cheaper than an ordinary dress, as having a less quantity of material in it; it would be more durable, because the lower edge of the skirt would not be exposed to attrition upon the ground; it would be more convenient, owing to less frequent changes to suit the weather; it would require a less bulky wardrobe; it could more easily be made cooler in summer, and warmer in winter, than ladies' ordinary dresses; and it would be conducive to health, by the avoidance of damp skirts hanging m about the feet and ankles in wet weather. Some of these arguments, it may be mentioned, were adduced by the editress herself, some by a Boston physician, who wrote in the Lily. The fashion did not fail to make itself apparent in various parts of the United States. The Washington Telegraph, the Lycoming Gazette, the Hartford Times, the Rochester Daily Times, the Syracuse Journal, and other newspapers, noticed the adoption of the costume at those places; and generally with much commendation, as having both elegance and convenience to recommend it, and not being open to any charge of indelicacy, except by a misuse of that word. In the autumn of the same year, an American lady lectured on the subject in London, dressed in black satin jacket, skirt, and trousers, and urged upon English ladies the adoption of the new costume; but this, and all similar attempts in England, failed to do more than raise a foolish merriment on the subject. Even in America the Bloomer Costume, as it was called, speedily became a thing of the past. As by a sort of reaction, the monstrosity of cumbrous skirts has since, in all countries, become more monstrous, until men are beginning to ask what over-proportion of the geographical area the ladies mean to occupy. To revive a joke of John Wilkes -Mrs. Bloomer took the sense of the ward on the subject; but Fashion took the non-sense, and carried it ten to one. |