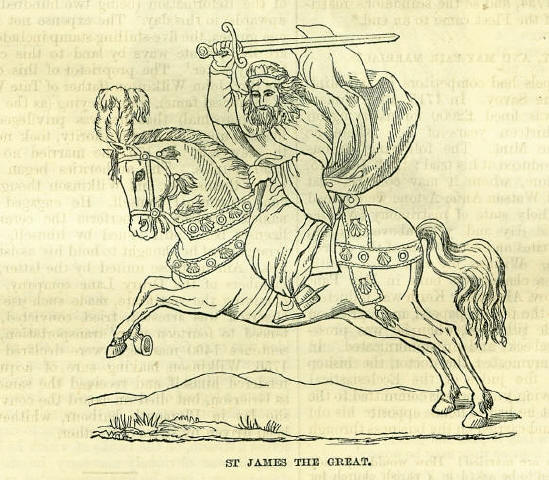

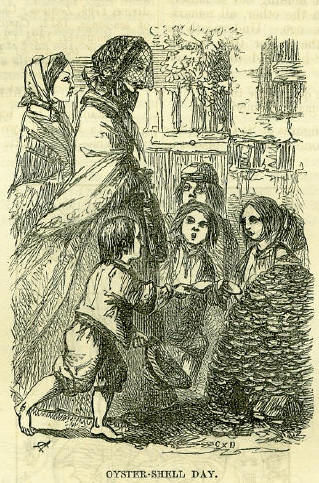

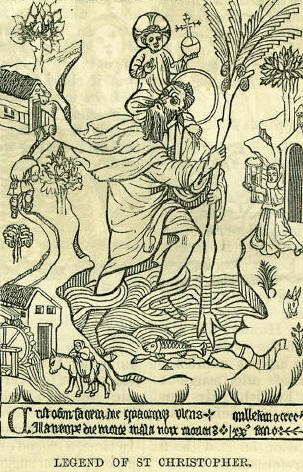

25th JulyBorn: Rev. William Burkitt, author of Expository Notes on the New Testament, 1650, Hitcham, Northamptonshire; Mrs. Elizabeth Hamilton, authoress of the Cottagers of Glenburnie, 1758, Belfast. Died: Constantius Chlorus, Roman emperor, 306, York (Eboracum); Nicephorus I, Greek emperor, killed in Bulgaria, 811; Thomas à Kempis, reputed author of the Imitation of Christ, 1471, Mount St. Agnes, near Zwoll; Philip Beroaldus (the elder), eminent classic commentator, 1505, Bologna; Ferdinand I, emperor of Germany, 1564, Vienna; Robert Fleming, author of The Fulfilling of the Scripture, 1694, Rotterdam; Baron Friederich von der Trenck, author of the Memoirs, guillotined at Paris, 1794; William Romaine, eminent divine, 1795, London; Charles Dibdin, celebrated author of sea-songs, 1814, Camden Town, London; William Sharp, engraver, 1824, Chiswick; William Savage (Dictionary of the Art of Printing), 1844, Kennington; James Kenney, dramatic writer, 1849, London. Feast Day: St. James the Great, the Apostle. St. Christopher, martyr, 3rd century. St. Cueufas, martyr in Spain, 304. Saints Thea and Valentina, virgins, and St. Paul, martyrs, 303. St. Nissen, abbot of Mountgarret, Ireland. ST. JAMES THE GREATThe 25th of July is dedicated to St. James the Great, the patron saint of Spain. According to legendary lore, James preached the gospel in Spain, and afterwards returning to Palestine, was made the first bishop of Jerusalem. While preaching from the summit of the temple, he was thrown over the battlements, and killed by the Jews. Some Spanish converts, however, who had followed him to Jerusalem, rescued his holy relics, and conveyed them to Spain, where they were miraculously discovered in the eighth century.  The Spaniards hold St. James in the highest veneration, and if their history was to be believed, with good reason. At the battle of Clavijo, fought in the year 841 between Ramiro, king of Leon, and the Moors, when the day was going hard against the Christians, St. James appeared in the field, in his own proper person, armed with a sword of dazzling splendour, and mounted on a white horse, having housings charged with scallop shells, the saints peculiar heraldic cognizance; he slew sixty thousand of the Moorish infidels, gaining the day for Spain and Christianity. The great Spanish order of knighthood, Santiago de Espada-St. James of the Sword -was founded in commemoration of the miraculous event; giving our historian Gibbon occasion to observe that, 'a stupendous metamorphosis was performed in the ninth century, when from a peaceful fisherman of the Lake of Gennesareth, the apostle James was transformed into a valorous knight, who charged at the head of Spanish chivalry in battles against the Moors. The gravest historians have celebrated his exploits; the miraculous shrine of Compostella displayed his power; and the sword of a military order, assisted by the terrors of the inquisition, was sufficient to remove every objection of profane criticism.' The city of Compostella, in Galicia, became the chief seat of the order of St. James, from the legend of his body having been discovered there. The peculiar badge of the order is an blood-stained sword in the form of a cross, charged, as heralds term it, with a white scallop shell; the motto is Rubel ensis sanguine Arabum-Red is the sword with the blood of the Moors. The banner of the order, preserved in the royal armory at Madrid, is said to be the very standard which was used by Ferdinand and Isabella at the conquest of Granada. But, as it bears the imperial, double-headed eagle of the Emperor Charles V, we may accept the story, like many other Spanish ones, with some reservation. On this banner, St. James is represented as he appeared at the battle of Clavijo; and the accompanying engraving is a correct copy of the marvellous apparition. But it was not at Clavijo alone that St. James has appeared and fought for Spain; he has been seen fighting, at subsequent times, in Flanders, Italy, India, and America. And, indeed, his powerful aid and influence has been felt even when his actual presence was not visible. St. James's Day has ever been considered auspicious to the arms of Spain. Grotius happily terms it, a day the Spaniards believed fortunate, and through their belief made it so. Charles V conquered Tunis on that day; but on the following anniversary, when he invaded Provence, he was not by any means so successful. The shrine of St. James at Compostella, was a great resort of pilgrims, from all parts of Christendom, during the medieval period; and the distinguishing badge of pilgrims to this shrine, was a scallop shell worn on the cloak or hat. In the old ballad of the Friar of Orders Gray, the lady describes her lover as clad, like herself, in 'a pilgrim's weedes:' And how should I know your true love From many an other one? by his scallop shell and hat, And by his sandal shoon. The adoption of the shell by the pilgrims to the shrine of St. James, is accounted for in a legend, which relates, that when the relics of the saint were being miraculously conveyed from Jerusalem to Spain, in a ship built of marble, the horse of a Portuguese knight, alarmed, we may presume, at so extraordinary a barge, plunged into the sea with its rider. The knight was rescued, and taken on board of the ship, when his clothes were found to be covered with scallop shells. Erasmus, however, in his Pilgrimages, has given us a more feasible account. One of his interlocutors meets a pilgrim, and says: 'What country has sent you safely hack to us, covered with shells, laden with tin and leaden images, and adorned with straw necklaces, while your arms display a row of serpents' eggs'?' 'I have been to St. James of Compostella,' replies the pilgrim. 'What answer did St. James give to your professions?' 'None; but he was seen to smile, and nod his head, when I offered my presents; and the held out to me this imbricated shell.' 'Why that shell rather than any other kind?' 'Because the adjacent sea abounds in them.' Curiously enough, a scallop shell is borne at the present day by pilgrims in Japan; and in all probability its origin, as a pilgrim's badge, both in Europe and the East, was derived from its use as a primitive cup, dish, or spoon. And this idea is corroborated by the crest of Dishing-ton, an old English family, being a scallop shell-a punning allusion to the name and the ancient use of the shell as a dish. And we may add, as a proof of the once ancient popularity of pilgrimages to Compostella, that seventeen English peers and eight baronets carry scallop shells in their arms as heraldic charges. There is some folk lore connected with St. James's Day. They say in Herefordshire: Till St. James's Day is past and gone, There may be hops or they maybe none; implying the noted uncertainty of that local crop. Another proverb more general is -'Whoever eats oysters on St. James's Day, will never want money.' In point of fact, it is customary in London to begin eating oysters on St. James's Day, when they are necessarily somewhat dearer than afterwards; so we may presume that the saying is only meant as a jocular encouragement to a little piece of extravagance and self-indulgence.  In this connection of oysters with St. James's Day, we trace the ancient association of the apostle with pilgrims' shells. There is a custom in London which makes this relation more evident. In the course of the few days following upon the introduction of oysters for the season, the children of the humbler class employ themselves diligently in collecting the shells which have been cast out from taverns and fish-shops, and of these they make piles in various rude forms. By the time that old St. James's Day (the 5th of August) has come about, they have these little fabrics in nice order, with a candle stuck in the top, to be lighted at night. As you thread your way through some of the denser parts of the metropolis, you are apt to find a cone of shells, with its votive light, in the nook of some retired court, with a group of youngsters around it, some of whom will be sure to assail the stranger with a whining claim-Mind the grotto! by which is meant a demand for a penny wherewith professedly to keep up the candle. It cannot be doubted that we have here, at the distance of upwards of three hundred years from the Reformation, a relic of the habits of our Catholic ancestors. THE LEGEND OF ST. CHRISTOPHERThis is a very early and obscure saint. Be is generally represented as a native of Lycia, who suffered martyrdom under Decius, in the third century. Butler conceives that he took the name of Christopher (q. d. Christum fero), to express his ardent love for the Redeemer, as implying that he carried that sacred image constantly in his breast. When a taking religious idea was once fairly set agoing in the middle ages, it grew under favour of the popular imagination, always tending more and more to a tangible form. In time, a legend obtained currency, being obviously a mere fiction suggested by the saint's name. It was said that his original occupation was to carry people across a stream, on the banks of which he lived. As such, it was obviously necessary he should be a strong man; ergo, he was represented as a man of gigantic stature and strength.  One evening, a child presented himself to be conveyed over the stream. At first his weight was what might be expected from his infant years; but presently it began to increase, and so went on till the ferryman was like to sink under his burden. The child then said: 'Wonder not, my friend, I am Jesus, and you have the weight of the sins of the whole world on your back!' When this legend had become thoroughly established, the stalwart figure of Christopher wading the stream, with the infant Jesus on his shoulder became a favourite object for painting and carving in churches. St. Christopher was in time regarded as a kind of symbol of the Christian church. A tutelage over fishing came to be one of his minor attributes, and it was believed that where his image was, the plague could not enter. The saint has come to have an interesting place in the history of typography, in consequence of a wood-engraving of his figure, supposed to be of date about 1423, being the earliest known example of that art. Besides the figure of the saint, there is a mill-scene on one side of the river, and a hermit holding out a lantern for the saint's guidance on the other, all remark-ably well drawn for the age. Underneath is an inscription, assuring the reader that on the day he sees this picture, he could die no evil death: Christofori faciem die quacumque tueris, Illa nempe die morte mala'' non morieris. None of the many carved figures of St. Christopher approached in magnitude one which was placed in the church of Notre Dame at Paris. It was erected by a knight of the name of Antoine des Essars, who was arrested with his brother for some malversation; the latter was beheaded, but the former dreamed that the saint broke his prison-bars and carried him off in his arms. The dream was verified, for in a few days he was declared innocent. He in consequence erected this wooden giant, which, after being an object of popular wonder for many generations, was removed in 1785. Erasmus, in his Colloquy of the Shipwreck, describing a company threatened with that calamity, says: 'Did no one think of Christopher? I heard one, and could not help smiling, who, with a shout, lest he should not be heard, promised to Christopher who dwells in the great Church at Paris, and is a mountain rather than a statue, a wax image as great as himself. He had repeated this more than once, bellowing as loud as he could, when the man who happened to be next to him, touched him with his finger, and hinted: 'You could not pay that, even if you set all your goods to auction.' Then the other, in a voice now low enough, that Christopher might not hear him, whispered: 'Be still, you fool! Do you fancy I am speaking in earnest? If I once touch the shore, I shall not give him a tallow candle!' CHARLES DIBDINSouthampton has had the peculiar honour of giving to England two most prolific and popular versifiers-Isaac Watts and Charles Dibdin were born there. Unlike in character and calling, they were curiously akin in activity and versatility, and specially in the readiness and ease with which they wrote rhymes, which now and then broke into genuine poetry. Dibdin was the eighteenth child of a Southampton silversmith; and his mother was nearly fifty years of age at his birth, in 1745. His parents designed him for the church, and sent him to Winchester, but his love for music was an overpowering passion; and, to be near the theatres, he ran off to London, and, while a boy of sixteen, managed to bring out at Covent Garden The Shepherd's Artifice, an opera in two acts, written and composed by himself. A few years afterwards he made his appearance as an actor with fair success. In 1778, he was appointed musical director of Covent Garden theatre at a salary of £10 a week. As a playwright, a composer of operas, a theatrical manager, and a builder of theatres, he spent his years with chequered fortune. In 1796, he opened the Sans Souci in Leicester Street, Leicester Square; and in an entertainment, entitled The Whim of the Moment, he occupied the stage for nearly ten years as sole performer, author, and composer. For the Sans Souci, he wrote about a thousand songs. The naval war with France was meanwhile at its height, Nelson was in his full career of glory, and the nation was wild with delight and pride in the exploits of its seamen. Dibdin became the bard of the British navy. He sang his multitudinous songs in Leicester Fields with a patriotic fervour truly contagious; his notes were caught up and repeated over sea and land; and, it is said, did more to recruit the navy than all the press-gangs. To Dibdin the beau-ideal of the English sailor-a being of reckless courage, generosity, and simpleheartedness-is largely attributable. In 1805, he sold Sans Souci, and opened a music-shop in the Strand, which landed him in bankruptcy. The government gave him a pension of £200, which was withdrawn in a fit of parsimony, and then restored. He was attacked with paralysis at the end of 1813, and died in 1814 at his house in Camden Town, in those days a rural suburb of London. The great mass of Dibdin's songs are now forgotten, but a choice few the world will not willingly let die. Some of his operas still keep the stage, and are always heard with pleasure; for no musician has ever excelled him in sweetness of melody and just adaptation of sound to sense. He wrote about a dozen novels, a History of the Stage, and an account of his professional life. One of his sons, Thomas Dibdin, pursued a similar life to his father, producing a host of theatrical pieces, but with less success. He died in indigence in 1841. Dr. Dibdin, the celebrated bibliographer, was a nephew of Charles Dibdin; and it was on the death of Thomas, the doctor's father, that Charles wrote the fine ballad of Poor Tent Bowling. WILLIAM SHARP, THE ENGRAVERThis celebrated engraver-in-line was born on the 29th of January 1749, at Haydon Yard, in the Minories, where his father carried on the business of a gunmaker. Apprenticed to a bright engraver, his first essay was made upon a pewter-pot, and one of his earliest essays was a small plate of an old lion which had been in the Tower menagerie for thirty years. He next began to engrave pictures from the old masters, and some plates from designs by Stothard; but he greatly excelled in copying the original feeling of Sir Joshua Reynolds; his portrait of John Hunter, the surgeon, is one of the finest prints in the world. Sharp, though he attained the highest excellence in his profession, was in politics and religious belief a visionary and an enthusiast. He was several times arrested and examined before the privy-council, on suspicion of treasonable practices; and on one occasion, after he had been plagued with many irrelevant questions, he pulled out of his pocket a prospectus for subscribing to his portrait of General Kosciusko, after West, which he was then engraving; and handing it to Mr. Pitt and Mr. Drundas, he requested them to put their names down as subscribers, which set the council laughing, and he was soon liberated. He shewed less shrewdness in other matters. No imposture was too great for his belief, and no evidence sufficiently strong to disabuse his mind. The doctrines of Mesmer, the rhapsodies of the notorious Richard Brothers, and the gross delusion of Joanna Southcott, in turn found in him a warm disciple; and in the last case an easy dupe. For Jacob Bryan, an irregular Quaker, but a fervid fanatic, Sharp professed a fraternal regard; so he set him up in business as a copper-plate printer; and one morning, Sharp found Jacob on the floor, between his two printing presses, groaning for the sins of the people. Sharp believed the millennium to be at hand, and that he and Brothers were to march with their squadrons for the New Jerusalem, in which, by anticipation, Sharp effected purchases of estates! Upon a friend remonstrating with him, that none of his preparations for the journey provided for the marine passage, Sharp replied, Oh, you'll see, there will be an earthquake; and a miraculous transportation will take place.' Nor can Sharp's faith or sincerity on this point be distrusted; for he actually engraved two plates of the portrait of the prophet Brothers, fully believing that one plate would not print the great number of impressions that would be wanted when the advent should arrive; and he added to each this inscription: 'Fully believing this to be the man appointed by God, I engrave Ids likeness.-W. SHARP.' The wags of the day generally chose to put the comma-pause after the word 'appointed.' Sharp's belief in Joanna Southeott's delusion was equally absurd; when the surgeons were proceeding to an anatomical investigation of the causes of her dissolution, Sharp maintained that she was not dead, but in a trance! And, subsequently, when he was sitting to Mr. Haydon for his portrait, he predicted that Joanna would reappear in the month of July 1822. 'But, suppose she should not?' said Haydon. 'I tell you she will,' retorted Sharp; 'but if she should not, nothing should shake my faith in her divine mission.' And those who were near Sharp's person during his last illness, state that in this belief he died. He lies interred near Dr. Loutherbourg and Hogarth, in Chiswick church-yard. |