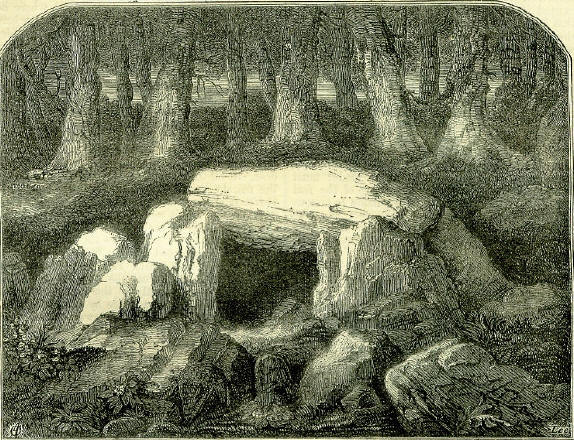

18th JulyBorn: Dr. John Dee, astrologer and mathematician, 1527, London; Zachary Ursinus, celebrated German divine, 1534, Breslau; Dr. Robert Hooke, natural philosopher, 1635, Freshwater, Isle of Wight; Saverio Bettinelli, Italian author, 1718, Mantua; Gilbert White, naturalist, 1720, Selborne. Died: Pope John XVIII, 1009; Godfrey of Bouillon, king of Jerusalem, 1100; Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch), great Italian poet and sonneteer, 1374, Arqua, near Padua; Abraham Sharp, mechanist and calculator, 1742, Little Horton, Yorkshire; Thomas Sherlock, bishop of London, 1761, Fulham. Feast Day: St. Symphorosa, and her seven sons, martyrs, 120. St. Philastrius, bishop of Brescia, confessor, 4th century. St. Arnoul, martyr, about 534. St. Arnoul, bishop of Metz, confessor, 640. St. Frederic, bishop of Utrecht, martyr, 838. St. Odulph, canon of Utrecht, confessor, 9th century. St. Bruno, bishop of Segni, confessor, 1125. REV. GILBERT WHITEGilbert White is one of those happy souls who without painful effort, in the quiet pursuit of their own pleasures, have registered their names among the dii minores of literature. Biography scarcely records a finer instance of prolonged peaceful and healthful activity. His life seems to have been a perfect idyll. Selborne, with which White's name is indissolubly associated, is a village of one straggling street, about fifty miles from London, situated in a corner of Hampshire, bordering on Sussex. In the house in which he spent his life and in which he died, White was born on the 18th July 1720. His father was a gentleman of comfortable income, who educated him for a clergyman. He gained a fellow-ship at Oxford, and served as a proctor, to the surprise of his family, who thought it a strange office for one of his habits, and that he would be more observant of the swallows in the Christchurch meadows than the undergraduates in the High Street. He had frequent opportunities of accepting college livings, but his fondness for 'the shades of old Selborne, so lovely and sweet,' outweighed every desire for preferment. In his native village he settled, and the ample leisure secured from clerical duty he devoted to the minute and assiduous study of nature. He was an outdoor naturalist, and kept diaries in which the progression of the seasons, and every fact which fell under his eye, were entered with the exactness which a merchant gives to his ledger. The state of the weather, hot or cold, sunny or cloudy, the variations of the wind, of the thermometer and barometer, the quantity of rain-fall, the dates on which the trees burst into leaf and plants into blossom, the appearance and disappearance of birds and insects, were all accurately recorded. On the 21st of June, he tells us that house-martins, which had laid their eggs in an old nest, had hatched them, and got the start of those which had built new nests by ten days or a fortnight. He relates that dogs come into his garden at night, and eat his gooseberries; that rooks and crows destroy an immense number of chaffers; and that, but for them, the chaffers would destroy everything. His neighbours' crops, fields, and gardens, cattle, pigs, poultry, and bees were all looked after. He chromcled his ale and beer, as they were brewed by his man Thomas. The births of his nephews and nieces were duly entered, to the number of sixty-three. Selborne was a choice home for a naturalist. It is a place of great rural beauty, and of thorough seclusion. The country around is threaded with deep sandy lanes overgrown with stunted oaks, hazels, hawthorns, and dog-roses, and the banks are covered with primroses, strawberries, ferns, and almost every English wild-flower. In White's time, the roads were usually impassable for carriages in winter, and Selborne held little intercourse with the world. Once a year, White used to visit Oxford, leaving the registration of the weather to Thomas, who was well versed in his master's business. Happily, White's brothers had an interest in natural history only second to his own, and with them and other congenial friends he kept up a lively correspondence. It was by the persuasion of his brother Thomas, a fellow of the Royal Society, that he was induced to overcome a horror of publicity and reviewers, and to issue in quarto, in 1789, the Natural History of Selborne, compiled from a series of letters addressed to Thomas Pennant and Daines Barrington. Four years after-wards, he died, 26th June 1793, aged seventy-three. His habits were regular and temperate, his disposition social and cheerful; he was a good story-teller, and a favourite with young and old, at home and abroad. His autobiography is in his book, and ardent admirers who have haunted Selborne for further particulars concerning the philosophical old bachelor, have learned little more than was spoken by an old dame, who had nursed several of the White family: 'He was a still, quiet body: there wasn't a bit of harm in him, I'll assure ye, sir; there wasn't indeed!' The paternal acres of White at Selborne are, of course, to the great body of British naturalists, a classic ground. By a happy chance, they have fallen into the possession of an eminent living naturalist, fully competent to appreciate the sentimental charm which invests them, and of a social character to banish envy among his brethren even for such an extraordinary piece of good fortune-Mr. Thomas Bell. Long may they be in hands so liberal, under an eye so discriminative, bound to a heart so sympathetic with all the moods and pulses of nature! WAYLAND SMITHS CAVEThis now well-known monument of a remote antiquity stands in the parish of Ashbury, on the western boundaries of Berkshire, among the chalk-hills which form a continuation of the Wiltshire downs, in a district covered with ancient remains. It is simply a primitive sepulchre, which, though now much dilapidated, has originally consisted of a rather long rectangular apartment, with two lateral chambers, formed by upright stones, and roofed with large slabs. It was, no doubt, originally covered with a mound of earth, which in course of time has been in great part removed. It belongs to a class of monuments which is usually called Celtic, but, if this be a correct denomination, we must take it, no doubt, as meaning Celtic during the Roman period, for it stands near a Roman road, the Ridgway, which was the position the Romans chose above all others, while the Britons in the earlier period, if they had any high-roads at all, which is very doubtful, chose in preference the tops of hills for their burial-place. A number of early sepulchral monuments might be pointed out in different parts of our island, of the same class, and more important than Wayland Smith's Cave, but it has obtained an especial celebrity through two or three circumstances.  In the first place, this is the only monument of the kind which we find directly named in an Anglo-Saxon document. It happened to be on the line of boundary between two Anglo-Saxon estates, and, therefore, became a marked object. In the deed of conveyance of the estate in which this monument is mentioned, of a date some time previous to the Norman Conquest, it is called Welandes Smiththan, which means Weland's Smithy, or forge, so that its modern name, which is a mere slight corruption from the Anglo-Saxon one, dates itself from a very remote period. In the time of Lysons, to judge from his account of it, it was still known merely by the name of Wayland Smith, so that the further corruption into Wayland Smith's Cave appears to be of very recent date. It is also worthy of remark, that the Anglo-Saxon name appears to prove that in those early times the monument had been already uncovered of its earth, and was no longer recognised as a sepulchral monument, for the Anglo-Saxons would hardly have given the name of a forge, or smithy, to what they knew to be a tomb; so that we have reason for believing that many of our cromlechs and monuments of this description had already been uncovered of their mounds in Anglo-Saxon times. They were probably opened in search of treasure. But, perhaps, the most curious circumstance of all connected with this monument is its legend. It has been the popular belief among the peasantry in modem times, that should it happen to a traveller passing this way that his horse cast a shoe, he had only to take the animal to the cave,' which they supposed to be inhabited by an invisible, to place a groat on the copestone, and to withdraw to a distance from which he could not see the operation, and on his return, after a short absence, he would find his horse properly shod, and the money taken away. To explain this, it is necessary only to state that, in the primitive Anglo-Saxon and Teutonic mythology, Weland was the mythic smith, the representative of the ancient Vulcan, the Greek Hephaistos. We have a singular proof, too, of the extreme antiquity of the Berkshire stouy, in a Grecian popular legend which has been preserved by the Greek scholiast on Apollonius Rhodius. We are told that one of the localities which Hephaistos, or Vulcan, especially haunted was the Vulcanian islands, near Sicily; and the scholiast tells us, that 'it was formerly said that, whoever chose to carry there a piece of unwrought iron, and at the same time deposit the value of the labour, would, on presenting himself there on the following morning, find it made into a sword, or whatever other object he had desired.' We have here, at this very remote period, precisely the same legend, and connected with the representative of the same mythic character, as that of the Berkshire cromlech; and we have a right, therefore, to assume that the same legend had existed in connection with the same character, at that far-distant period before the first separation of the different branches of the Teutonic family, and when Weland, and Hephaistos, and Vulcan were one. All our readers know how skilfully our great northern bard, Sir Walter Scott, introduced the Berkshire legend of Wayland Smith into the romance of Kenilworth, and he has thus given a celebrity to the monument which it would never otherwise have enjoyed. Yet, although in his story the mythic character of Wayland Smith is lost, and he stands before us a rather common-place piece of humanity, yet every reader must feel interested in knowing something of the real character of the personage, whose name is famous through all medieval poetry in the west, and who held a prominent place in the heathen mythology of our early Saxon forefathers. His story is given in the Eddas. Weland, as we have said, was the Vulcan of the Teutonic mythology. He was the youngest of the three sons of Wade, the all, or demi-god; and when a child, his father intrusted him to the dwarfs in the interior of the mountains, who lived among the metals, that they might instruct him in their wonderful skill in forging, and in making weapons and jewellery, so that, under their teaching, the youth became a wonderful smith. The scene of this legend is placed by the Edda in Iceland, where the three brothers, like all Scandinavian heroes, passed much of their time in hunting, in which they pursued the game on skates. In the course of these expeditions, they settled for a while in Ulfdal, where, one morning, finding on the banks of a lake three Valkyrier, or nymphs, with their elf garments beside them, they seized and took them for their wives, and lived with them eight years, at the end of which period the Valkyrier became tired of their domestic life, and flew away during the absence of their husbands. When the three brothers returned, two of them set off in search of their fugitive spouses; but Weland remained patiently at home, working in his forge to make gold rings, which he strung upon a willow-wand, to keep them till the expected return of his wife. There lived at this time a king of Sweden, named Niduth, who had two sons, and a daughter named. Baudvild, or, in the Anglo-Saxon form of the name, Beadohild. The possession of a skilful smith, and the consequent command of his labour, was looked upon as a great prize; and when Niduth heard that Weland was in Ulfdal, he set off, with a strong body of his armed followers, to seek him. They arrived at his hut while he was away hunting, and, entering it, examined his rings, and the king took one of them as a gift for his daughter, Baudvild. Weland returned at night, and made a fire in his hut to roast a piece of bear's flesh for. his supper; and when the flames arose, they gave light to the chamber, and Weland's eyes fell on his rings, which he took down and counted, and thus found that one was missing. This circumstance was to him a cause of joy, for he supposed that his wife had returned and taken the ring, and he laid him down to slumber; but while he was asleep, King Niduth and his men returned, and bound him, and carried him away to the king's palace in Sweden. At the suggestion of the queen, they hamstringed him, that he might not be able to escape, and placed him in a forge in a small island, where he was compelled to work for the king, and where anybody but the latter was forbidden to go under severe penalties. Weland brooded over his revenge, and accident offered him the first opportunity of indulging it. The greediness of the king's two sons had been excited by the reported wealth of Weland's forge, and they paid a secret visit to it, and were astonished at the treasures which the wily smith presented to their view. He promised that they should have them all, if they would cone to him in the utmost secrecy early next morning; but when they arrived, he suddenly closed the door, cut off their heads, and buried their bodies in the marshy ground on which the forge was built. He made of the skulls, plated with silver, drinking-cups for the king's table; of their eyes, gems for the queen; and of their teeth, a collar of pearls, which he sent as a present to the princess. The latter was encouraged to seek Weland's assistance to mend her ring, which had been accidentally broken; and, to conceal the accident from her father, she went secretly to the forge, where the smith completed his vengeance by offering violence to her person, and sent her away dishonoured. While he had been meditating vengeance, Weland had also been preparing the means of escape, and now, having fitted on a pair of wings of his own construction, he took flight from his forge. He halted for a moment on the wall of the enclosure of the palace, where he called for the king and queen, told then all the circumstances of the murder of their sons and the dishonour of their daughter, and then continued his flight, and was heard of no more. The Princess Baudvild, in due time, gave birth to a daughter, who also was a celebrated hero of the early German mythology. It will be remarked, that the lameness of Weland is accounted for in a different manner from that of Vulcan in the more refined mythology of the classical ages. As the various branches of the Teutonic race spread towards the west, they carried with them their common legends, but soon located then in the countries in which they settled, and after a few generations they became established as local legends. Thus, among the Scandinavians, the scene of Weland's adventures was laid in Iceland and Sweden; while among the earlier Teutons, it appears to have been fixed in some part of Germany; and the Anglo-Saxons, no doubt, placed it in England. We have found the name, and one of the legends connected with it, fixed in a remote corner of Berkshire, where they have been preserved long after their original import was forgotten. It is one of the most curious examples of the great durability of popular legends of all kinds. We know that the whole legend of Weland the smith was perfectly well known to the Anglo-Saxons to a late period of their monarchy. THE AUTHOR OF 'BARON MUNCHAUSEN'Who is there that has not, in his youth, enjoyed The Surprising Travels and Adventures of Barron Munchausen, in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, dc., a slim volume-all too short, indeed-illustrated by a formidable portrait of the baron in front, with his broad-sword laid over his shoulder, and several deep gashes on his manly countenance? I presume they must be few. This book appears to have been first published, in a restricted form, by one Kearsley, a bookseller in Fleet Street, in 1786; a few years afterwards, it was reprinted, with a considerable addition of palpably inferior matter, by H. D. Symonds of Paternoster Row. The author's name was not given, and it has, till a very recent date, remained little or not at all known. There can hardly be a more curious piece of neglected biography. The author of the baron's wonderful adventures is now ascertained to have been Rodolph Eric Raspe, a learned and scientific German, who died in the latter part of 1794 at Mucross, in the south of Ireland, while conducting some mining operations there. Much there was of both good and ill about poor Raspe. Let us not press matters too hard against one who has been able to contribute so much to the enjoyment of his fellow-creatures. But, yet, let the truth be told. Be it known, then, that this ingenious man, who was born at Hanover in 1737, commenced life in the service of the land-grave of Hesse Cassel as professor of archaeology, inspector of the public cabinet of medals, keeper of the national library, and a councillor, but disgraced himself by putting some of the valuables intrusted to him in pawn, to raise money for some temporary necessities. He disappeared, and was advertised for by the police as the Councillor Raspe, a man with red hair, who usually appeared in a scarlet dress embroidered with gold, but some-times in black, blue, or gray clothes. He was arrested at Clausthal, but escaped during the night, and made his way to England, where he chiefly resided for the remainder of his days. It will be heard with pain, that before this lamentable downbreak in life, Raspe had manifested decided talents in the investigation of questions in geology and mineralogy. He published at Leipsic, in 1763, a curious volume in Latin, on the formation of volcanic islands, and the nature of petrified bodies. In 1769, there was read at the Royal Society in London, a Latin paper of his, on the teeth of elephantine and other animals found in North America, and it is surprising at what rational and just conclusions he had d arrived. Raspe had detected the specific peculiarities, distinguishing these teeth from those of the living elephant, and saw no reason for disbelieving that some large kinds of elephants might formerly live in cold climates; being exactly the views long after generally adopted on this subject. The exact time of the flight to England is not known; but in 1776, he is found publishing in London a volume on Some German Volcanoes and their Productions - necessarily extinct volcanoes-thus again shewing his early apprehension of facts then little if at all understood, though now familiar. And in the ensuing year, he gave forth a translation of the Baron Born's Travels in Tameswar, Transylvania, and Hungary-a mineralogical work of high reputation. In 1780, Horace Walpole speaks of him as 'a Dutch savant,' who has come over here, and who was preparing to publish two old manuscripts 'in infernal Latin,' on oil-painting, which proved. Walpole's own idea that the use of oil-colours was known before the days of Van Eyck. 'He is poor,' says the virtuoso of Strawberry Hill; the natural sequel to which statement is another three months later: 'Poor Raspe is arrested by his tailor.' I have sent him a little money,' adds Walpole, 'and he hopes to recover his liberty; but I question whether he will be able to struggle on here.'. By Walpole's patronage, the book was actually published in April 1781. In this year, Raspe announced a design of travelling in Egypt, to collect its antiquities; but while the scheme was pending, he obtained employment in certain mines in Cornwall. He was residing as 'storemaster' at Dalcoath Mines, in that district, when he wrote and published his Travels of Baron Munchausen. Previously to this time, his delinquency at Cassel having become known, the Royal Society erased his name from their honorary list; and he threatened, in revenge, to print in the form of their Philosophical Trans-actions the Unphilosophical Transactions of the English sevens, with their characters. This matter seems to have blown over. And now we have to introduce our hero in a new connection with English literature. The facts are fully known to us, and there can be no harm in stating them. Be it understood, then, that Raspe paid a visit to Scotland in the summer and autumn of 1789, for the professed purpose of searching in various districts for minerals. It was announced in the Scots Magazine for October, that he had discovered copper, lead, iron, cobalt, manganese, &c.; that the marble of Tiree, the iron of Glengarry, and the lead on the Breadalbane property were all likely to turn out extremely well. From Sutherland he had brought specimens of the finest clay; there was 'every symptom of coal,' and a fine vein of heavy spar had been discovered. He had now begun his survey of Caithness. From another source we learn that a white saline marble in Icolmkill had received his attention. As to Caithness, here lay probably the loadstone that had brought him into Scotland, in the person of Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster, a most benevolent gentleman, who, during a long life, was continually engaged in useful projects, chiefly designed for the public benefit, and of novel kinds. With him Raspe took up his abode for a considerable time, at his spray-beaten castle on the Pentland Firth; and members of the family still speak of their father's unfailing appreciation of the infinite intelligence and facetiousness of his visitor's conversation. Sir John had, some years before, discovered a small vein of yellow mrmdick on the moor of Skinnet, four miles from Thurso. The Cornish miners he consulted told him that the mumdick was itself of no value, but a good sign of other valuable minerals not far off. In their peculiar jargon, 'white mundick was a good horseman, and always rode on a good load.' Sir John now employed Raspe to examine the ground, not designing to mine it himself, but to let it to others if it should turn out favourably. For a time, this investigation gave the proprietor very good hopes. Masses of a bright heavy mineral were brought to Thurso Castle, as foretastes of what was coming. But, in time the bubble burst, and it was fully concluded by Sir John Sinclair, that the ores which appeared were all brought from Cornwall, and planted in the places where they were found. Miss Catherine Sinclair has often heard her father relate the story, but never with the slightest trace of bitterness. On the contrary, both he and Lady Sinclair always said, that the little loss they made on the occasion was amply compensated by the amusement which the mineralogist had given them, while a guest in their house. Such was the author of Baron, Munchausen, a man of great natural penetration and attainments, possessed of lively general faculties, and well fitted for a prominent position in life. Wanting, however, the crowning grace of probity, he never quite got his head above water, and died in poverty and obscurity. It will be observed that, in his mining operations in Caithness, he answers to the character of Dousterswivel in the Antiquary; and there is every reason to believe that he gave Scott the idea of that character, albeit the baronet of Ulbster did not prove to be so extremely imposed upon as Sir Arthur Wardour, or in any other respect a prototype of that ideal personage. Of all Raspe's acknowledged works, learned, ingenious, and far-seeing, not one is now remembered, and his literary fame must rest with what he probably regarded as a mere jet& d' esprit. It may be remarked that a translation of the Baron into German was published by the ingenious Bürger in 1787. This was very proper, for most of the marvels were of German origin. Some of those connected with hunting are to be found, 'in a dull prosy form, in Henry Bebel's Facetice, printed in Strasburg in 1508; others of the tales are borrowed from Castiglioni's Cortegians, and other known sources.' |