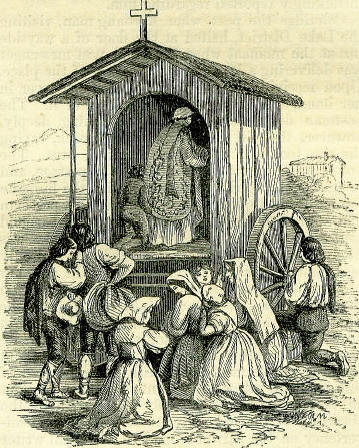

19th JulyBorn: Conrad Vorstius, or Vorst, celebrated German divine, 1569, Cologne; Gilbert Sheldon, archbishop of Canterbury, erecter of the Sheldon theatre at Oxford, 1598, Staunton, Staffordshire; John Martin, celebrated painter, 1789, Haydon Bridge, Northumberland. Died: Dr. John Caius, physician and author, founder of Caine College, Cambridge, 1573, Cambridge; William Somerville, author of The Chase, 1742, Edstone, Warwickshire; Nathaniel Hooke, author of the Benson history, 1764, Hedsor; Captain Matthew Flinders, Australian explorer, 1814; Professor John Playfair, writings in natural philosophy, geology, &e., 1819, Edinburgh; Iturbide, Mexican leader, shot at Padillo, 1824. Feast Day: St. Macrina, virgin, 379. St. Arsenius; anchoret, 449. St. Symmachus, pope and confessor, 514. St. Vincent de Paul, founder of the Lazarites, confessor, 1660. BATTLE OF HALIDON HILLJuly 19, 1333, is the date of a remarkable battle between the Scots and English at Halidon Hill. Stowe's account of the conflict is picturesque and interesting, though not in every particular to be depended on. The youthful Edward III had laid siege to Berwick; and a large Scottish army, animated, doubtless, by-recollections of Bannockburn, came to relieve the town. 'At length,' says Stow: the two armies appointed to fight, and setting out upon Halidon Hill [near Berwick], there cometh forth of the Scots camp a certain stout champion of great stature, who, for a fact by him done, was called Turnbull. He, standing in the midst between the two armies, challenged all the Englishmen, any one, to fight with him a combat. At length Robert Venale, knight, a Norfolk-man, requesting licence of the king, being armed, with his sword drawn, marcheth toward the champion, meeting by the way a certain black mastiff dog, which waited on the champion, whom with his sword he suddenly strake, and cut him off at his loins; at the sight whereof the master of the dog slain was much abashed, and in his battle more wary and fearful; whose left hand and head also afterward this worthy knight cut off. After this combat both the armies met, but they fighting scarce half an hour, certain of the Scots being slain, they closed their army (which was in three) all in one battle; but at length flying, the king followed them, taking and chasing them into lakes and pits for the space of five miles. The honest chronicler sets down the loss of the Scots infantry on this occasion at 35,000, besides 1300 horsemen, being more than ten times the loss of the British at Waterloo. Such exaggerations are common among the old chroniclers, and historians generally, before the days of statistics. More probably, the slain on the side of the vanquished did not exceed two thousand. It will be heard with some surprise, that there is preserved a song, in the English language, written at the time upon this victory of King Edward. It appears as one of a series, composed upon the king's wars, by one Lawrence Minot, of whom nothing else is known. It opens with a strain of exultation over the fallen pride of the Scots, and then proceeds to a kind of recital of facts A little fro that foresaid town [Berwick], Halidon Hill, that is the name, There was cracked many a crown Of wild Scots, and als of tame. There was their banner borne all down, To mak sic boast they war' to blame; But, nevertheless, ay are they bonne To wait England with sorrow and shame. Shame they have, as I hear say; At Dundee now is done their dance; And went they must another way, Even through Flanders into France. On Philip Valois fast cry they, There for to dwell, and him avance; And nothing list them than of play, Sin' them is tide this sexy chance. This sary chance is them betide, For they were false and wonder fell; For cursed caitiffs are they kid, And full of treason, sooth to tell. Sir John the Cumin had they hid, In Italy kirk they did him quell; And therefore many a Scottis bride With dole are dight that they must dwell. The bard then changes to another strain, in which he joyfully proclaims how King Edward had revenged Bannockburn: Scots out of Berwick and of Aberdeen, At the Bannockburn war ye too keen; There slew ye many saikless, as it was seen, And now has King Edward wroken it, I ween: It is wroken, I ween, weel worth the while, War it with the Scots, for they are full of guile. Where are the Scots of St. John's town? The boast of your banner is beaten all down; When ye boasting will bide, Sir Edward is boune For to kindle you care, and crack your crown; He has cracked your crown, well worth the while; Shame betide the Scots, for they are full of guile. THE CAMPAGNA OF ROME DURING THE MONTH OF JULYIn Italy, July is the month of bread; August, the month of wine: in the first, the Roman peasants reap; in the second, they gather the grapes. The harvest-people come, for the most part, from the Neapolitan provinces, especially the Abruzzi mountains; they leave their homes, carrying their families with them, pitch their tents every night for sleeping, and might be taken for Bedouin hordes or gypsy tribes. They hire their labour for the small sum of twenty baiocchi a day, out of which they manage to save in order to carry home a little treasure. The Roman Campagna is by no means an uncultivated desert; the greater part is ploughed, and produces wheat, but, on account of miasma, it is uninhabited and uninhabitable, and the cultivators of the ground are obliged to come from great distances. On Sunday, the priests attend and perform mass for the reapers in a kind of movable church drawn by oxen, and provided with all the necessary apparatus for the celebration of the service.  Mass in the Campagna is a very picturesque scene: strong brawny men in their shirt-sleeves and short trousers; women in the satin dress which was the one worn at their marriage, and is used for the Sunday costume ever after; children of every age, from the nursling playing on its mother's breast or peacefully sleeping in the cradle; hunters, who sometimes join the assembly with their dogs; the priest officiating in the wooden chapel suspended between the two-wheeled wagon; still further, the tents supported by two poles; the horses tranquilly grazing; the harnessed oxen, which will soon carry away the nomade edifice to another spot; the beautiful blue hills which surround the verdant, golden landscape; the burning sun shedding torrents of light and fire over all nature; the deep silence, scarcely interrupted by the words of the priest, the prayers of the crowd, the neighing of the horses, or the, humming of insects-all unite to form a scene interesting both in a physical and moral sense. When the reaping is over, then comes the operation of thrashing, which they call la trita. For this purpose, they prepare a level thrashings floor on which to spread the sheaves; fasten together six horses, and make them tread over the straw until the grain has all fallen out. When finished, they rake up the straw, stack it, and pile up the grain into heaps, on the top of which they place a cross. LETTER FRANKINGLong before the legal settlements of the post-office in the seventeenth century, the establishment of the post was kept up at the instance of the reigning sovereign for his special service and behoof. Under the Stuarts, the postal resources of the kingdom were greatly developed, and all classes were made to share alike in the benefits of the post. Cromwell made many improvements in the post-office, though the reasons which he assigned for so doing, 'that they will be the best means to discover and prevent many dangerous and wicked designs against the commonwealth,' are open to exception and censure, viewed as we view post-office espionage at this date. In the reign of the second Charles, the post-office for the first time became the subject of parliamentary enactments, and it was at this time that the franking privilege, hitherto enjoyed by the sovereign and the executive alone, was extended to parliament. A committee of the House of Commons, in the year 1735, reported 'that the privilege of franking letters by the knights, &c., chosen to represent the Commons in parliament, began with the creating of a post-office in the kingdom by act of parliament.' The bill here referred to was introduced into the House of Commons in 1660, and it contained a proviso securing the privilege. The account of the discussion on the clause in question is somewhat amusing. Sir Walter Earle proposed that 'members' letters should come and go free during the time of their sittings.' Sir Heneage Finch (afterwards Lord. Chancellor Finch) said, indignantly, 'It is a real poor mendicant proviso, and below the honour of the House.' Many members spoke in favour of the measure, Serjeant Charlton urging that 'letters for counsel on circuit went free.' The debate was nearly one-sided, but the speaker, Sir Harbottle Grimstone, on the question being called, refused for a considerable time to put it, saying, 'He felt ashamed of it.' The clause, however, was eventually put, and carried by a great majority. When the bill, with its franking proviso, was sent up to the Lords, they threw out the clause, as there was no provision made in it, 'that the Lords' own letters should pass free!' Some years later, this omission was supplied, and both Houses had the privilege guaranteed to them, neither Lords nor Commons feeling the arrangement below their dignity. It is important to notice, that at the time of which we are speaking, the post-office authorities had much more control over the means of conveyance than they have at the present day. With both inland and packet conveyance the postmasters-general had entire control. At the present day, contracts are made with the different railway companies, &c., for inland conveyance, and the packet-service is under the management of the Board of Admiralty. Without this knowledge, it would be difficult to account for the vast and heterogeneous mass of articles which were passed free through the post-office by a wide stretch of the privilege under notice. In old records of the English post-office still preserved, we find lists of these franked consignments; the following, culled from a number of such, is sufficient to indicate their character: 'Fifteen couple of hounds, going to the king of the Romans with a free pass.' 'Two maid-servants, going as laundresses to my Lord Ambassador Methuen' 'Doctor Crichton, carrying with him a cow and divers necessaries.' 'Three suits of cloaths, for some nobleman's lady at the court of Portugal.' 'Two bales of stockings for the use (?) of the ambassador to the crown of Portugal.' 'A deal-case, with four flitches of bacon, for Mr. Pennington of Rotterdam.' When the control of the packet-service passed out of the hands of the post-office authorities, and when the right of franking letters became properly sanctioned and systematised, we hear no more of this kind of abuses of privilege. The franking system was henceforth confined to passing free through the post any letter which should be endorsed on the cover with the signature of a member of either house of parliament. It was not necessary, however, that parliament should be in session, or that the correspondence should be on the affairs of the nation (though this was the original design of the privilege) to insure this immunity from postage; and this arrangement, as might have been expected, led to various forms of abuse. Members signed large packets of covers at once, and supplied them to friends in large quantities; sometimes they were sold; they have been known to have been given to servants in lieu of wages, the servants selling them again in the ordinary way of business. Nor was this all. So little precaution seems to have been used, that thousands of letters passed through the post-office with forged signatures of members. To such an extent did these and kindred abuses accumulate, that whereas in 1715, £24,000 worth of franked correspondence passed through the post-office, in 1763 the amount had increased to £170,000. During the next year, viz., in 1764, parliament enacted that no letter should pass free through the post-office unless the whole address was in the member's own handwriting, and his signature attached likewise. It is obvious that this arrangement would materially lessen the frauds practised upon the public revenue of the country. But even these precautions were not sufficient, for fresh regulations were rendered necessary in the year 1784. This time it was ordered that all franks should be dated-the month to be given in full-and further, that all such letters should be put into the post on the same day. From 1784 to the date of the penny-postage era, the estimated value of franked letters was £80,000 annually. No further reforms were, however, attempted, till Sir Rowland Hill advocated the very radical and indispensable reform of entirely abrogating the privilege. In the bill, which through his unceasing energy was introduced into parliament in 1839, no provision was made such as had existed for a couple of centuries. Writing on this subject, and having mentioned the name of the founder of the penny-post system, we may advert to an anecdote which has been mistakingly reported regarding him. Coleridge the poet, when a young man, visiting the Lake District, halted at the door of a wayside inn at the moment when the rural post-messenger was delivering a letter to the barmaid of the place. Upon receiving it, she turned it over and over in her hand, and then asked the postage of it. The postman demanded a shilling. Sighing deeply, however, the girl handed the letter back, saying she was too poor to pay the required sum. The young poet at once offered to pay the postage, and in spite of the girl's resistance, which the humane tourist deemed quite natural, did so. The postman had scarce left the place, when the young barmaid confessed that she had learned all that she was likely to know from the letter; that she had only been practising a preconceived trick; she and her brother having agreed that a few hieroglyphics on the back of a post-letter should tell her all she wanted to know, whilst the letter would contain no writing. 'We are so poor,' she added, 'that we have invented this manner of corresponding and franking our letters.' Mr. Hill, having heard of this incident, introduced it into his first pamphlet on postal reform, as a lively illustration of the absurdity of the old system. It was by an inadvertency on the part of a modern historical writer that Mr. Hill was ever described as the person to whom the incident happened. DRINKING-FOUNTAIN IN 1685The desirableness of providing public drinking-fountains, similar to those which originated a few years ago in Liverpool, and are now becoming general in London and other large towns, seems to have occurred to some benevolent persons almost two centuries ago. Sir Samuel Morland, who was a most ingenious as well as benevolent character, purchased a house at Hammersmith in 1684, where, for many years, he chiefly resided. Observing the scarcity of good drinking-water in his neighbourhood, and knowing how seriously the poor would suffer from the want of such a necessary of life, he had a well sunk near his own house, and constructed over it an ingenious pump, a rare convenience in those days, and consigned it gratuitously for the use of the public. A tablet, fixed in the wall of his own house, bore the following record of his benefaction: 'Sir Samuel Morland's Well, the use of which he freely gives to all persons, hoping that none who shall come after him will adventure to incur God's displeasure, by denying a cup of cold water (provided at another's cost, and not their own) to either neighbour, stranger, passenger, or poor thirsty beggar. July 8, 1685.' The pump has been removed, but the stone bearing the inscription was preserved in the garden of the house, afterwards known by the name of Walbrough House. Sir Thomas Morland was an interesting character. He was the son of a country clergyman in Berkshire, and was born about 1625. He was educated at Winchester School, and at Magdalen College, Cambridge. In 1653, he went to Sweden in the famous embassy of Bulstrode Whitelock, and subsequently became assistant to Secretary Thurloe. Afterwards he was sent by Cromwell to the Duke of Savoy, to remonstrate against the persecution of the Waldenses; and, on his return, he published a History of the Evangelical Churches of the Valley of Piedmont. But he distinguished himself chiefly by his mechanical inventions; among which are enumerated the speaking-trumpet, the fire-engine, a capstan for heaving anchors, and the steam-engine. If not the original inventor of these, as is questioned, he certainly effected great improvements in them. He constructed for himself a coach, with a movable kitchen in it, so fitted with clockwork machinery, that he could broil steaks, roast a joint of meat, and make soup, as he travelled along the road. The side-table in his dining-room was furnished with a large fountain of water; and every part of his house bore evidence of his ingenuity. He was created a baronet by Charles II in 1660, and died in 1696, having been four times married. LARGE-WHEEL VEHICLES IN 1771Many ingenious inventions go completely out of sight, when the accounts relating to them are confined to newspapers and journals of temporary interest; unless some historian of industrial matters fixes them in a book, or in a cyclopaedic article, down they go, and subsequent inventors may re-invent the self-same things, quite unconscious of what had been done. We believe that this is, to a considerable extent, the ease with Mr. Moore's large-wheel vehicles brought out in London in 1771. Of course, few readers now a days need to be told that a vehicle with large wheels will move more easily than one with wheels of smaller diameter; like as the latter will move more easily than one that rests upon mere rollers. Reduced friction and greater leverage result; and it depends upon other considerations how far this enlargement of wheel may be carried: in other words, a great number of circumstances combine to settle the best size for a carriage-wheel to work in the streets of London. Mr. Moore has no halo of glory around him; but he certainly succeeded in shewing, to the wonderment of many Londoners, that large wheels do enable vehicles to roll with comparative ease over the ground. The journals and magazines of that year contain many such announcements as the following: On Saturday evening, Mr. Moore's new constructed coach, which is very large and roomy, andis drawn by one horse, carried six persons and the driver, with amazing ease, from Cheapside to the top of Highgate Hill. It came back at the rate of ten miles an hour, passing coaches-and-four, and all other carriages it came near on the road. Another account gives a description of the vehicle itself, which was evidently a remarkable one on other accounts besides the size of wheel: Mr Moore has hung the body, which is like that of a common coach reversed, between two large wheels, nine feet and a half in diameter, and draws it with a horse in shafts. The passengers sit sideways within; and the driver is placed upon the top of the coach. On one occasion, Mr. Moore went in his curious coach, with five friends, to Richmond, where he had the honour of being presented to George III, who passed great commendations on the vehicle. Mr. Moore appears not to have forgotten the exigencies of good traffic, and the heavy pull to which horses are often subjected in the streets of the metropolis. We read (19th July) that Mr. Moore experimented on a cart with two wheels, and drawn by two horses, which conveyed twenty-six sacks of coals from Mr. De Paiba's wharf, in Thames Street, to Mr. Moore's house in Cheapside, and repeated this in four successive journeys-an amount of work which, it was said, would require twice as many horses with a cart of ordinary construction. On another day, we are told something about the construction of the vehicle: Mr. Moore's new invented coal-carriage, the wheels of which are fifteen feet high, passed through the streets, attended by a great concourse of people. Two horses abreast drew two chaldrons and two sacks of coals with more ease and expedition than the common carts do one chaldron with three horses at length. And on another occasion, 'the coal-carriage was tried on Friday evening, with thirty-one sacks, making two chaldrons and a half, drawn by two horses only to the foot of Holborn Hill, when a third was put to it, to help them up the hill. This they performed with as much ease as one chaldron is commonly done by three horses.' Notices of this kind ceased to appear about the autumn of the year; and Mr. Moore, for reasons to us unknown, passed into the limbo of forgotten inventors. |