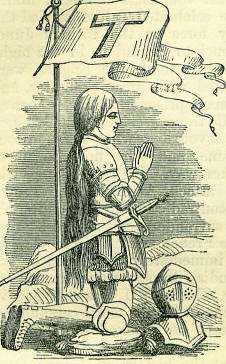

17th JulyBorn: Dr. Isaac Watts, well-known divine and writer of hymns, 1674, Southampton; Adrian Reland, oriental scholar and author, 1676, Ryp, North Holland. Died: Robert Guiscard the Norman, Duke of Apulia,1085, Corfu; Jacques Arteveldt, brewer in Ghent, and popular leader, slain, 1344; John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, English general in France, killed before Châtillon, 1453; Janet, Lady Glammis, burned as a witch on Castle Hill of Edinburgh, 1537; Marchioness of Brinvilliers, noted poisoner, executed at Paris, 1676; Sir William Wyndham, noted Tory orator, 1740, Wells, Sonersetshire; Charlotte Corday, assassin of Marat, guillotined, 1793; Dr. John Roebuck, distinguished manufacturing chemist, and founder of the Carron Ironworks, 1794; Charles, second Earl Grey, prime minister to William IV, 1845. Feast Day: Saints Speratus and his companions, martyrs, 3rd century. St. Marcellina, eldest sister of St. Ambrose, about 400. St. Alexius, confessor, 5th century. St. Ennodius, bishop of Pavia, confessor, 521. St. Turninus, confessor, 8th century. St. Leo IV, pope and confessor, 855. THE MARCHIONESS OF BRINVILLIERSIt is a melancholy fact that the progress of civilization, along with the innumerable benefits which it confers on the human race, tends to develop and bring forth a class of offences and crimes which are almost, if not wholly, unknown in the earlier and less sophisticated stages of society. Whilst violence and rapine are characteristics of primitive barbarism and savage independence, commercial fraud and murder by treachery but too often spring up as their substitutes in peaceful and enlightened times. As long as human nature continues the same, and its leading principles have ever hitherto been unchanging, so long must the spirit of evil find some mode of expression, veiled though it may be under an infinite variety of disguises, and yet not without undergoing a gradual softening down which optimists would fondly regard as a promise of its ultimate suppression. The crime of poisoning, it has often been remarked, is like assassination-the offspring of a polished and voluptuous age. In proof of this, we need only look to its horrible and astounding frequency in Italy and France during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. One of the most notable instances of its occurrence is the case of the Marchioness of Brinvilliers, whose nefarious practices, coupled with her distinguished rank, have exalted her to the very pinnacle of infamy. She was the daughter of M. Dreux d'Aubray, who held the office of lieutenant-civil in the capital of France during the reign of Louis XIV. In 1651, she was married to the Marquis of Brinvilliers, a son of the president of the Chamber of Accounts, and the heir of an immense fortune, to which his wife brought a very considerable accession. The marchioness is described as a woman of most pre-possessing appearance, both as regards agreeableness of person and as impressing the beholder with a sense of virtue and amiability. Never was the science of physiognomy more completely stultified. Beneath that fair and attractive exterior was concealed one of the blackest and most depraved hearts that ever beat within a female bosom. A career of degrading sensuality had, as afterwards appeared by her own confession, exerted on her its natural and corrupting influence almost from her childhood. No special evidence of its fruits, however, became prominently manifest till her acquaintance with a certain Sieur Godin, commonly called St. Croix, who had made her husband's acquaintance in the course of military service, and for whom the latter conceived such an overweening affection that he introduced him into, and made him an inmate of, his house. An intimacy, which was soon converted into a criminal one, sprang up between him and the marchioness, who also not long afterwards procured a separation from her husband on the ground of his pecuniary recklessness and mismanagement. Freed now from all the restraints by which she had hitherto been held, she indulged so shamelessly her unlawful passion for St. Croix, that public decency was scandalised, and her father, after several ineffectual attempts to rouse M. de Brinvilliers to a sense of his conjugal degradation, procured a lettre its cachet, by which her paramour was committed to the Bastile. Here St. Croix became acquainted with an Italian named Exili, an adept in poisons, who taught him his arts, and on their release, after about a twelvemonth's confinement, became an inmate of his house. The intimacy of St. Croix with the marchioness was at the same time renewed, but more cautiously, so as to save appearances, and even to enable the latter to regain the affection of her father; a necessary step towards the accomplishment of the schemes in view. Avarice and revenge now conspired with illicit love, and the horrid design was conceived of poisoning her father and the other members of her family, so as to render herself sole heir to his property. Tutored by St. Croix, she mixed up poison with some biscuits which she distributed to the poor, and, more especially, to the patients of the Hötel Dieu, as an experiment to test the quantity necessary for a fatal effect. Having thus prepared herself for action, the marchioness commenced with the murder of her father, which she effected by mixing some poison with his broth when he was residing at his country seat. The symptoms ordinarily exhibited in such cases ensued, but the patient did not die till after his return to Paris. No suspicions on this occasion seem to have rested on the marchioness, who forthwith proceeded to effect the deaths of her two brothers, one of whom succeeded their father in his office of lieutenant-civil, and the other was a counsellor of the parliament of Paris. This she accomplished by means of a man named La Chaussée, who had formerly lived as a footman with St. Croix, and then transferred his services to the brothers D'Aubray, who occupied together the same house. Under the guidance of his former master, this miscreant administered poison to them on various occasions, which destroyed first the lieutenant and then the counsellor; but so well had the semblance of fidelity been maintained, that the latter bequeathed to La Chaussée a legacy of a hundred crowns in consideration of his services. One member of the marchioness's family still remained, her sister Mademoiselle D'Aubray, whose suspicions, how-ever, were now aroused against her sister, and by her vigilance and circumspection she escaped the snares laid for her life. The singular deaths of M. D'Aubray and his sons excited considerable attention, and the belief came to be strongly entertained that they had been poisoned. Yet no suspicion alighted on the marchioness or St. Croix, and they might have succeeded in escaping the punishment due to their crimes, had it not been for a singular accident. Whilst the latter was busied one day with the preparation of his poisons, the mask which he wore to protect himself from their effects dropped off, and he was immediately suffocated by the pernicious vapours. Having no relations to look after his property, it was taken possession of by the public authorities, who, in the course of their rummaging, discovered a casket, disclosing first a paper in the handwriting of the deceased, requesting all the articles contained in it to be delivered unexamined to the Marchioness de Brinvilliers. These consisted of packets of various kinds of poison, a promissory-note by the marchioness in St. Croix's favour for 1500 livres, and a number of her letters to him, written in the most extravagantly amatory strain. Even now, had it not been for the imprudence of La Chausse'e in presenting sundry claims on St. Croix's succession, it might have been difficult to substantiate his guilt and that of his employers. He was indicted at the instance of the widow of the lieutenant-civil, the younger D'Aubray; and having been brought before the parliament of Paris, was condemned to be broken alive on the wheel, after having been first subjected to the torture for the discovery of his accomplices. On the rack, he made a full confession; in consequence of which a demand was made on the authorities of Liege for the tradition to the French government of the Marchioness of Brinvilliers, who had fled thither on hearing of the proceedings instituted after the death of St. Croix. This abandoned woman had, previous to quitting Paris, made various attempts, by bribery and otherwise, to obtain possession of the fatal casket; but finding all these ineffectual, made her escape by night across the frontier into the Netherlands. Given up here by the Council of Sixty of Liege to a company of French archers, she was conducted by them to Paris, not without many offers, on her part, of large sums of money to the officers to let her go, and also an endeavour to commit suicide by swallowing a pin. Previous to, and during her trial, she made the most strenuous declarations of her innocence; but the accumulated proof against her was overwhelming; and, notwithstanding the very ingenious defence of her counsel, M. Nivelle, she was found guilty by the parliament, and condemned to be first beheaded and then burned. This sentence was pronounced on the 16th of July 1676, and executed the following day. On hearing the verdict against her, she retracted her former protestations, and made a full and ample confession of her crimes. One of the doctors of the Sorbonne, M. Pirot, who attended her as spiritual adviser during the twenty-four hours' interval between her sentence and death, has left a most fervid description of her last moments. According to his account, she manifested so sincere and pious a contrition for her enormities, and gave such satisfactory evidences of her conversion, that he, the confessor, would have been willing to exchange places with the penitent! The great painter, Le Brun, secured a good place for himself at her execution, with the view of studying the features of a condemned criminal in her position, and transferring them to his canvas. We are informed also, that among the crowds who thronged to see her die were several ladies of distinction. This last circumstance can hardly surprise us, when we recollect that, three quarters of a century later, the fashion and beauty of Paris sat for a whole day to witness, as a curious spectacle, the barbarities of the execution of Damiens. CHARLES VII OF FRANCE AND JEANNE DARC This day is memorable in the history of France, as that on which it may be considered to have been saved from the lowest state of helpless wretchedness to which foreign invasion had ever reduced that kingdom -at least, since the invasions of the Normans. Under a succession of princes, hardy raised above imbecility, torn to pieces by the feuds of a selfish and rapacious aristocracy, the kingdom of France had seen its crown surrendered to a foreigner, the king of England; its legitimate monarch, a weak-minded and slothful prince, had been driven into almost the last corner of his kingdom which was able to give him a shelter, and almost his last stronghold of any importance was in imminent danger of falling into the hands of his enemies, when, by a sudden turn of fortune, on the 17th of July 1429, Charles VII, relieved from his dangers, was crowned at Rheims, and all this wonderful revolution was the work of a simple peasant-girl. The very origin, and much of the private history of this personage are involved in mystery, and have furnished abundant subjects of discussion for historians. There is even some doubt as to her real name; but the French antiquaries seem now to be agreed that it was Dare, and not D'Arc, and that it had no relation whatever to the village of Arc, from which it was formerly supposed to be derived. Hence the name of Joan of Arc, by which she is popularly known in England, is a mere mistake. There was the more room for doubt about her name, because in France, during her lifetime, she was usually spoken of as La Pucelle, or The Maid; or at most she was called Jeanne la Pucelle-Jeanne the Maid. Jeanne was born at Donremi, a small village on the river Meuse, at the extremity of the province of Champagne, it is supposed in the latter part of the year 1410, and was the youngest child of a respectable family of labouring peasants, named Jacques and Isabelle Dare. The girl appears to have laboured from childhood under a certain derangement of constitution, physically and mentally, which rendered her mind peculiarly open to superstitious feelings, and made her subject to trances and visions. The prince within whose territory her native village stood, the Duke of Bar, was a stanch partisan of Charles VII, who, as he had never been crowned, was still only spoken of as the dauphin, while on the other side of the river lay the territory of the Duke of Lorraine, an equally violent adherent of the Duke of Burgundy and the English party. It is not surprising, therefore, if the mind of the young Jeanne became preoccupied with the troubles of her unhappy country; the more so as she appears to have possessed much that was masculine in form and character. Under such feelings she believed at length that she saw in her visions St. Michael the Archangel, who came to announce to her that she was destined to be the saviour of France, and subsequently introduced to her two female saints, Catherine and Margaret, who were to be her guides and protectors. She believed that her future communications came from these, either by their appearance to her in her trances, or more frequently by simple communications by a voice, which was audible only to herself. She stated that she had been accustomed to these communications four or five years, when, in June 1428, she first communicated the circumstance to her parents, and declared that the voice informed her that she was to go into France to the Dauphin Charles, and that she was to conduct him to Rheims, and cause him to be crowned there. An uncle, who believed at once in her mission, took her to Vaucouleurs, the only town of any consequence in the neighbourhood, to ask its governor, Robert de Baudricourt, to send her with an escort to the court of the dauphin; but he treated her statement with derision, and Jeanne returned with her uncle to his home. However, the story of the Maid's visions had now been spread abroad, and created a considerable sensation; and Robert de Baudricourt, thinking that her story and her enthusiasm might be turned to some account, sent a report of the whole affair to court. News arrived about this time of the extreme danger of Orleans, closely besieged by the English, and, in the midst of the excitement caused by this intelligence, Jeanne spoke with so much vehemence of the necessity of being immediately sent to the dauphin, that two young gentlemen of the country, named Jean de Novelonpont and Bertrand de Poulengi, moved by her words, offered to conduct her to Chinon, where Charles was then holding his court. This, however, was rendered unnecessary by the arrival of orders from the court, addressed to Robert de Baudricourt. It appears that Charles's advisers thought also that some use might be made of the maiden's visions, and Baudricourt was directed to send her immediately to Chinon. The inhabitants of Vaucouleurs subscribed the money to pay the expenses of her journey, her uncle and another friend bought her a horse, and Robert de Baudricourt gave her a sword; and she cut her hair short, and adopted the dress of a man. Thus equipped, with six attendants, among whom were the two young gentlemen just mentioned, Jeanne left Vaucouleurs on the 18th of February 1429, and, after escaping some dangers on the way, arrived at Chinon on the 24th of the same month. Such is the account of the commencement of Jeanne's mission, as it came out at a subsequent period on her trial. On her arrival at Chinon, Charles VII appears to have become ashamed of the whole affair, and it was not till the 27th, after various consultations with his courtiers and ecclesiastics, that he at length consented to see her. No doubt, every care had been taken to give effect to the interview, and when first introduced, although Charles had disguised himself so as not to be distinguished from his courtiers, among whom he had placed himself, she is said to have gone direct to him, and fallen on her knees before him, and, among other things to have said: 'I tell thee from the Lord, that thou art the true heir of France, and the son of the king.' This declaration had a particular importance, because it had been reported abroad, and seems to have been very extensively believed, that Charles was illegitimate. Charles now acknowledged that he was perfectly satisfied of the truth of the Maid's mission, and the belief in it became general, and was confirmed by the pretended discovery of a prophecy of Merlin, which foretold that France was to be saved by a virgin, who was to come from the Bosc-Chesnu. This, which meant the Wood of Oaks, was the name of the wood on the edge of which her native village of Domremi stood. Other precautions were taken, for it was necessary to dispel a prejudice which was rising against her-namely, that she was a witch-and she was carried to Poitiers, to be examined before a meeting of the ecclesiastics of Charles's party, who were assembled there, and who gave their opinion in her favour. She then returned to Chinon, while the young Duke of Alencon went to Blois, to collect the soldiers and the convoy of provisions and munitions of war, which the maiden was to conduct into Orleans. Jeanne now assumed the equipment and arms of a soldier, and was furnished with the usual attendance of the commander of an army. She went to Tours, to prepare for her undertaking; and while there, caused an emblematical standard to be made, and announced, on the authority of information received from her voices, that near the altar of St. Catherine, in the church of Fierbois, a sword lay buried, which had five crosses engraved on the blade, and which was destined for her use. An armourer of Tours was sent to the spot, and he brought back a rusty sword, which he said had been found under the circumstances she described, and which answered to her description. Reports of these proceedings had been carried into Orleans, and had raised the courage and resolution of the inhabitants and garrison, while the besiegers were greatly alarmed, for they also seem to have believed in Jeanne's mission in one sense, and expected that they would have to contend with Satanic agency. They believed from the first that she was a witch. At length, on the 27th of April, Jeanne left Blois with the convoy, accompanied by some of the military chiefs of the dauphin's party, and leading a force of 6000 or 7000 men. The enthusiasm she created produced an effect beyond anything that could be expected, and after serious disasters, the English were obliged, on the 8th of May, to raise the siege. The Maid herself carried the news of this great triumph to Charles VII, who was at Loche, and insisted on his repairing immedately to Rheims to be crowned. But, though he received her with honour, he exhibited none of her enthusiasm, and refused to follow her advice. In fact, his council had decided on following a totally different course of military operations to that which she wished; but they were at length persuaded to agree to the proposal for hastening the coronation, as soon as the course of the Loire between them and Rheims could be cleared of its English garrisons. The army was accordingly placed under the command of the Duke of Alencon, with orders to act by Jeanne's counsels. Gergeau, where the Duke of Suffolk commanded, was soon taken, and the garrison massacred. Having received considerable reinforcements, commanded by the Count of Vendöme, the Maid marched against the English forces, under the command of the celebrated Talbot, carried the bridge of Meung by force on the 15th of June, and reduced Beaugenci to capitulate in the night of the 17th. In their retreat, the English were overtaken and defeated with great slaughter, and Talbot himself was made prisoner. Charles shewed no gratitude for all these services, but listened to the councils of favourites, who were jealous of the maiden's fame, and who now began to throw obstacles in her way. He refused to yield to her proposal to attack Auxerre, and Troyes was only taken in contradiction to the dauphin's intentions. Chalons surrendered without resistance, and on the 16th, the French army came in view of Rheims, which was immediately abandoned by the English and Burgundian troops which formed its garrison. Next day, Charles VII. was crowned in the cathedral of Rheims with the usual ceremonies, and from this moment he received more openly the title of king. From this moment the history of Jeanne Dare is one only of ingratitude and treachery on the part of those whom she had served, and who, intending only to use her as an instrument, seem to have believed that her utility was now at an end. Further successes, however, attended the march of the army to Paris, where the mass of the English forces were collected, under the command of the regent, Bedford. To the great grief of the Maid, the attack upon Paris was abandoned; and during the operations against the French capital, an accident happened, which was felt as an unfortunate omen, and disturbed the mind of the Maid herself. In anger at some soldiers who had disobeyed her orders, she struck them with the flat of the sword of Fierbois, which was supposed to have been sent to her from Heaven, and the blade broke. It seemed to many as though her principal charm was broken with it. The events which occurred during the winter were comparatively of small importance, but on the approach of spring, Jeanne, who was detained unwillingly at court, made her escape from it, and hastened to Lagni, on the Marne, which was besieged by the English and Burgundians, where she displayed her usual enthusiasm, though she was haunted by sinister thoughts, and believed that her voices told her of approaching disaster. After the Easter of 1430, the Duke of Bedford prepared to attack the important town of Compiegne, and on his way had laid siege to Choisi; whereupon Jeanne left Lagni, repaired to Compiegne, and immediately hastened with a body of troops to relieve Choisi. But she was ill seconded, was frustrated in her design, and deserted by her troops, and was obliged to retire sorrowfully into Compiegne, which was soon afterwards regularly besieged. Jeanne displayed her usual courage, but she was an object of dislike to the French governor, and was no longer regarded with the same enthusiasm by the soldiery as before. On the 23rd of May, Jeanne went out of Compiegne at the head of a detachment of troops, to attack an English post, but after a desperate combat, she was obliged to retreat before superior numbers. As they approached Compiegne, one division of their pursuers made a rush to get before them, and cut off their retreat; on which the French fled in disorder, and, to their consternation, when they reached the head of the bridge of Compiegne, they found the barrier closed, and were left for some time in this terrible position. At length the barrier was opened, and the French struggled through, and then it was as suddenly closed again, before Jeanne-who, as usual, had taken her post in the rear-could get through. Whether this were done intentionally or not, is uncertain, but only a few soldiers were left with her, who were all killed or taken, while she managed to get clear of her assailants, and rode back to the bridge, but no notice was taken of her cries for assistance. In despair, she attempted to ride across the plain, but she was surrounded by her enemies, and one of the archers dragged her from her horse. She was thus secured and carried a prisoner to Marigni, where the Duke of Burgundy came to her. She was finally sold to the English, and delivered up as their prisoner in the month of October. During the intermediate period, the court of France had made no effort to obtain her liberation, or even shown any sympathy for her fate. The latter may be soon told. The question as to what should be done with the prisoner was soon taken out of the hands of her captors. No sooner was it known that the Maid was taken, than the vicar-general of the inquisition in France claimed her as a person suspected of heresy, under which name the crime of sorcery was included. When no attention had been paid to this demand-for it seems to have been thought doubtful on which of the two political sides of the great dispute the inquisition stood-another ecclesiastic, the bishop of Beauvais, a man of unscrupulous character, who was at this time devoted to the English interests, claimed her as having been taken within his diocese, and therefore under his ecclesiastical jurisdiction. After apparently some hesitation, it was determined to yield to this demand, and she was removed to Rouen, where Bedford had decided that the trial should take place, and where she appears to have been treated in her prison with great rigour and cruelty. Justice was as little observed in the proceedings on her trial, which began on the 21st of February 1431, and which ended, as might be expected, in her condemnation. The conduct of Bishop Cauchon and his creatures throughout was infamous in the extreme, but, on the whole, the proceedings resembled very much those of trials for witchcraft and heresy in general, and probably a very large portion of the inhabitants of England and France conscientiously believed her to be a witch. We judge, in such cases, by the sentiments of the age in which they occurred, and not by our own. On the morning of the 30th of May, Jeanne the Maiden was burned as a witch and heretic in the old market of Rouen, where a memorial to her has since been erected. A COMFORTABLE BISHOP OF OLD TIMESJuly 17, 1506, James Stanley was made bishop of Ely. He was third son of the noted Thomas Stanley, who was created Earl of Derby in 1485, for his conduct on Bosworth Field. It is thought to have been by the influence of his step-mother, the Countess of Richmond, the king's mother, that he attained the dignity; and her historian calls it 'the worst thing she ever did.' Stanley was, indeed, a worldly enough churchman-armis quam libris peritior, more skilled in arms than in books, he has been described-'ane great viander as any in his days,' so another contemporary calls him-yet not wanting in the hospitality and the bountifulness to churches and colleges, which ranked high among the clerical virtues of his age. Having been warden of Manchester, he lies buried in the old collegiate (now cathedral) church there, in a side-chapel built by himself. Some lines about him, which occur in a manuscript History of the Derby Family, are worth quoting for the quaintness of their style, and the pleasant tenderness with which they touch upon his character: ... little priest's metal was in him ... A goodly tall man, as was in all England, And sped well in matters that he took in hand. Of Ely many a day was he bishop there, Builded Somersame, the bishop's chief manere: Ane great viander as was in his days: To bishops that then was this was no dispraise. Because he was a priest, I dare do no less, But leave, as I know not of his hardiness: What priest hath a blow on the one ear, [will] suddenly Turn the other likewise, for humility? He would not do so, by the cross in my purse; Yet I trust his soul fareth never the worse. For he did acts boldly, divers, in his days, If he had been no priest, had been worthy praise. God send his soul to the heavenly company, Farewell, godly James, Bishop of Ely! A DANISH KING'S VISIT TO ENGLAND IN 1606On the 17th of July 1606, King Christian IV of Denmark arrived in England, on a visit to his brother-in-law and sister, the king and queen of Great Britain. Christian was a hearty man, in the prime of life, fond of magnificence, and disposed to enjoy the world while it lasted. His relative, King James, was of similar disposition, though of somewhat different tastes. To him nothing was more delightful than a buck-hunt. Christian had more relish for gay suppers, and the society of gay ladies. During the three weeks he spent in England, he was incessantly active in seeing sights and giving and receiving entertainments. The month of his stay,' says Wilson, 'carried with it a pleasing countenance on every side, and recreations and pastimes flew as high a flight as love mounted on the wings of art and fancy, the suitable nature of the season on time's swift foot, could possibly arrive at. The court, city, and some parts of the country, with banquetings, barriers, and other gallantry, besides the manly sports of wrestling and brutish sports of baiting wild beasts, swelled to such a greatness, as if there were an intention in every particular man, this way, to have blown up himself.' Another writer, named Roberts, describes the dresses of the king of Denmark's followers with all the gusto of a man-milliner. 'His pages and guard of his person were dressed in blue velvet embroidered with silver lace; they wore white hats with silver bands, and white and blue stockings. His trumpeters had white satin doublets, and blue velvet hose, trimmed with silk and silver lace; their cloaks were of sundry colours, their hats white with blue and gold bands. His common soldiers wore white doublets, and blue hose trimmed with white lace. His trumpeters were led by a sergeant in a coat of carnation velvet, and his drummer rode upon a horse, with two drums, one of each side the horse's neck, whereon he struck two little mallets of wood, a thing very admirable to the common sort, and much admired. His trunks, boxes, and other provision for carriage were covered with red velvet trimmed with blue silk.' Sir John Harrington, in a letter which has been printed in Park's Nuqae Antiquae, gives us a lively picture of the carousals which marked the presence of this northern potentate at the British court. I came here,' says Sir John, 'a day or two before the Danish king came; and from the day he did come, until this hour, I have been well-nigh overwhelmed with carousals and sports of all kinds. The sports began each day in such manner and such sort as well-nigh persuaded me of Mohammed's paradise. We had women, and indeed wine too, in such plenty as would have astonished each sober beholder. Our feasts were magnificent, and the two royal guests did most lovingly embrace each other at table. I think the Dane hath strangely wrought on our good English nobles; for those, whom I never could get to taste good liquor, now follow the fashion, and wallow in beastly delights. The ladies abandon their sobriety, and seem to roll about in intoxication. One day a great feast was held, and after dinner the representation of Solomon's temple, and the coming of the queen of Sheba, was made, or (as I may better say) was meant to have been made before their majesties, by device of the Earl of Salisbury and others. But, alas! as all earthly things do fail to poor mortals in enjoyment, so did prove our presentment thereof. The lady who did play the queen's part, did carry most precious gifts to both their majesties; but, forgetting the steps arising to the canopy, overset her caskets into his Danish majesty's lap, and fell at his feet, though I rather think it was in his face. Much was the hurry and confusion; cloths and napkins were at hand, to make all clean. His majesty then got up, and would dance with the queen of Sheba; but he fell down and humbled himself before her, and was carried to an inner chamber, and laid on a bed of state; which was not a little defiled with the presents of the queen, which had been bestowed upon his garments; such as wine, cream, beverage, jellies, cakes, spices, and other good matters. The entertainment and show went forward, and most of the presenters went back-ward, or fell down; wine did so occupy their upper chambers. Now did appear, in rich dress, Hope, Faith, and Charity. Hope did essay to speak, but wine rendered her endeavours so feeble that she withdrew, and hoped the king would excuse her brevity; Faith was then all alone, for I am certain she was not joined with good works, and left the court in a staggering condition; Charity came to the king's feet, and seemed to cover the multitude of sins her sisters had committed: in some sort she made obeisance, and brought gifts; but said she would return home, as there was no gift which Heaven had not already given his majesty. She then returned to Hope and Faith, who were both in the lower hall. Next came Victory, in bright armour, and presented a rich sword to the king, who did not accept it, but put it by with his hand; and by a strange medley of versification, did endeavour to make suit to the king. But Victory did not triumph long; for, after much lamentable utterance, she was led away, like a silly captive, and laid to sleep on the outer steps of the ante-chamber. Now, did Peace make entrance, and strive to get forward to the king; but I grieve to tell how great wrath she did discover unto those of her attendants; and, much contrary to her semblance, most rudely made war with her olive-branch, and laid on the pates of those who did oppose her coming. It is supposed to have been from the fact of the extreme bacchanalianism practised by Christian at home, that Shakspeare attributed such habits to the king in hamlet. The northern monarch was, however, duly anxious that his servants should practise sobriety. While he was in England, a marshal took care that any of them getting drunk should be sharply punished. Christian appears to have been quite an enthusiastic sight-seer. Although he was observed to express no approbation, he wandered incessantly about the metropolis, 'so that neither Fowles, Westminster, nor the Exchange escaped him.' He was also fond of the amusements of the tilting-yard. ' On a solemn tiltingday,' writes Sir Dudley Carleton, 'the king of Denmark would needs make one; and in an old black armour, without plume or basses, or any rest for his lance, he played his prizes so well, that Ogerio himself never did better. At a match between our king and him, running at the ring, it was his hap never almost to miss it; while ours had the ill-luck scarce ever to come near it, which put him in no small impatience.' The custom of making extravagant gifts at leave-takings was a characteristic feature of that sumptuous style of living amongst the high-born and wealthy, prevalent during the seventeenth century. James, so long as his exchequer continued pretty well replenished, distinguished himself by the magnificence of his princely largess. Indeed, taking into account the vast sums lavished on favourites, in addition to the debts of impoverished nobles, paid by him once and again, we are no ways astonished at the unkingly pecuniary straits to which he was continually reduced. A letter preserved amongst the state-papers, dated August 20, 1606, descriptive of the leave-taking between James and Christian of Denmark, narrates the following specimen of reckless profusion in the former, at a time when his necessities were so notoriously great, that his own subjects caricatured him as a beggar with his pockets turned inside out. 'The two kings,' says Sir Dudley Carleton, 'parted on Monday seven-night, as well pleased with each other as kings usually are upon interview. The gifts were great on our king's side, and only tolerable on the other. Imprimis, a girdle and hangers, with rapiers and daggers set with stones, which I heard valued by a goldsmith at £15,000. Then the old cup of state, which was the chief ornament of Queen Elizabeth's rich cupboard, of £1000 price; Item, a George, as rich as could be made in proportion; Item, a saddle embroidered with rich pearls; four war-steeds with their appropriate furniture and caparisons; two ambling geldings and two nags. To the king of Denmark's six counsellors were given £2000 worth of plate, and each of them a chain of £100; and to twenty-two gentlemen, chains of £50 apiece; and £1000 in money to the servants, the guard, and the sailors in the ship the king went in. The king of Denmark gave nothing to the king, as I heard, but made an offer of his second ship, in hope to have it requited with the White Bear; but that match was broken off by my Lord of Salisbury, and he had his own given back with thanks. To the king's children he gave £6000, and as much to the king's household.' Then follows a word-picture of a royal naval banquet in the year 1606, sketched with infinite humour, and strikingly illustrative of the social habits of that age. James takes leave of his brother on shipboard. The feasting was plenteous, but not riotous at court; but at the ships they played the seamen for good-fellowship. First at Chatham, where twenty-two of the king's were set out in their best equipage, and two especially, the Elizabeth Jonas and the Bear, trimmed up to feast in, betwixt which there was a large railed bridge built upon masts, and in the midst betwixt them both, butteries and kitchens built upon lighters and flat-boats. All things were there performed with such order and sumptuousness, that the king of Denmark confessed that he would not have believed such a thing could have been clone, unless he had seen it. At the Danish ships, where was the last farewell, what was wanting in meat and other ceremony was helped out with drink and gunshot; for at every health-of which there were twenty-the ship the kings were in made nine shot; and every other, there being eight in all, three; and the two blockhouses at Gravesend, where the fleet lay, each of them, six; at which I must tell you, by the way, our king was little pleased, and took such order in his own ships as not to be annoyed by the smell of powder; but good store of healths made him so hearty, that he bid. them at the last ' shoot and spare not,' and very resolutely commanded the trumpets to sound him a point of war. Give me the cups; And let the kettle to the trumpet speak, The trumpet to the cannoneer without, The cannons to the heaven, the heaven to earth, Now the king drinks to Hamlet. RICH BEGGARSThere are multitudes of instances of beggars who, amid squalor, rags, and dirt utterly miserable, contrive to amass considerable sums of money. For obvious reasons, they generally conceal their wealth during life, and it is only when the breath is out of their body that the golden hypocrisy is discovered. Usually, the hoarded coins are found sewn up in rags or straw-beds, or otherwise hidden in holes and corners; it is only in a few instances that the beggar ventures to invest his money in a bank. Among the many recorded examples of rich beggars, have been: Foreign countries are not without instances of like kind. Witness the case of Dandon, of Berlin, who died in 1812; he was competent to teach as a professor of languages during the day, and went out begging at night. After his death, 20,000 crowns were found secreted under the floor of his room. He had refused to see a brother for thirty-seven years, because he once sent him a letter without prepaying the postage. This Dandon, however, was an exampler rather of the miser than of the beggar, popularly so considered. Some beggars have been remarkable quite as much for their eccentricity, as for the amount of money they left behind them. Such was the case with William Stevenson, who died at Kilmarnock on the 17th of July 1817. Although bred a mason, the greater part of his life was spent as a beggar. About the year 1787, he and his wife separated, making this strange agreement-that whichever of them was the first to propose a reunion, should forfeit £100 to the other. According to the statements in the Scotch newspapers, there is no evidence that they ever saw each other again. In 1815, when about 85 years old, Stevenson was seized with an incurable disease, and was confined to his bed. A few days before his death, feeling his end to be near, he sent for a baker, and ordered twelve dozen burial-cakes, a large quantity of sugared biscuit, and a good supply of wino and spirits. He next sent for a joiner, and instructed him to make a good, sound, dry, roomy, 'comfortable' coffin. Next he summoned a grave-digger, whom he requested to select a favourable spot in the church-yard of Riccarton, and there dig a roomy and comfortable grave. This done, he ordered an old woman who attended him, to go to a certain nook, and bring out £9, to pay all these preliminary expenses: assuring her that she was remembered in his will. Shortly after this he died. A neighbour came in to search for his wealth, which had been shrouded in much mystery. In one bag was found large silver pieces, such as dollars and half-dollars, crowns and half-crowns; in a heap of musty rags, was found a collection of guineas and seven-shilling pieces; and in a box were found bonds of various amounts, including one for £300-giving altogether a sum of about £900. A will was also found, bequeathing £20 to the old woman, and most of the remainder to distant relations, setting aside sufficient to give a feast to all the beggars who chose to come and see his body ' lie in state.' The influx was immense; and after the funeral, all retired to a barn which had been fitted up for the occasion; and there they indulged in revelries but little in accordance with the solemn season of death. One curious circumstance regarding a beggar connected with the town of Dumfries, we can mention on excellent authority: a son of his passed through the class of Humanity (Latin), in the university of Edinburgh, under the care of the present professor (1863), Mr. Pillans. |