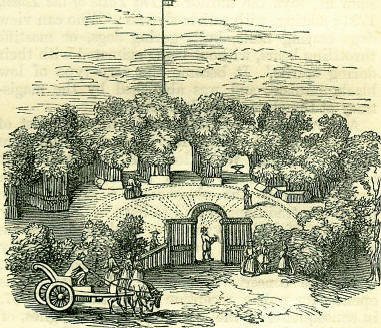

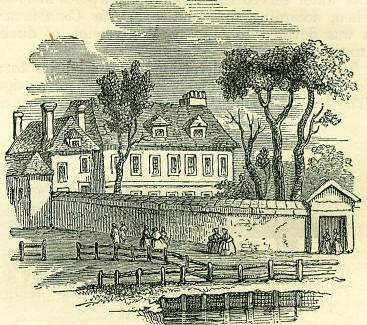

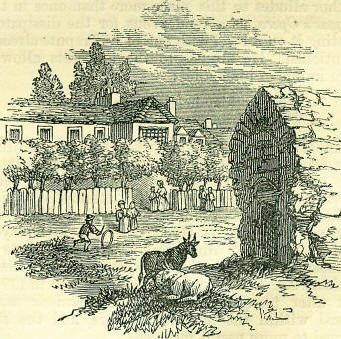

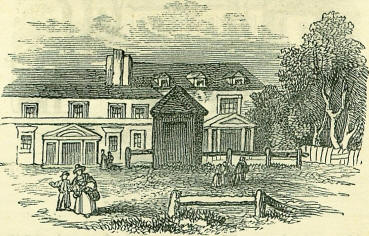

16th JulyBorn: Carneades, founder of the 'New Academy' school of philosophy, 217 B.C., Cyrene; Joseph Wilton, sculptor, 1722, London; Sir Joshua Reynolds, celebrated painter, 1723, Plympton, Devonshire. Died: Anne Askew, martyred at Smithfield, 1546; Tommaso Aniello (by contraction Masaniello), celebrated revolutionary leader, murdered by the populace at Naples, 1647; John Pearson, bishop of Chester, author of Exposition of the Creed, 1686, Chester; Francois Le Tellier, Marquis de Louvois, chancellor of France, 1691, Paris; Dr. Thomas Yalden, poet, 1736; Peter III, czar of Russia, husband to the Empress Catharine, strangled, 1762; Jean Louis Delolme, writer on the British constitution, 1 806; John Adolphus, historical writer, 1845, London; Margaret Fuller Ossoli, American authoress, perished at sea, 1850; Pierre Jean de Beranger, distinguished French lyrical poet, 1857, Paris. Feast Day: St. Eustathius, confessor, patriarch of Antioch, 338. St. Elier, or Helier, hermit and martyr. MARGARET FULLER OSSOLINot in England nor in France is the influence of women on society so active and so manifest as in New England. The agitation there for Women's Rights is merely an evidence of actual power, seeking its recognition in civic insignia. Every student of American society has noted the wide diffusion of intellectual ability, along with an absence of genius, or the concentration of eminent mental gifts in individuals. There is an abundance of cleverness displayed in politics, letters, and arts-there is no want of daring and ambition-but there is a strange lack of originality and greatness. The same is true of the feminine side of the people. A larger number of educated women, able to write well and talk well, it would be difficult to find in any European country, but among them all it would be vain to look for a Madame de Staël, or a Miss Martineau. Perhaps those are right who cite Margaret Fuller as the fairest representative of the excellences, defects, and aspirations of the women of New England. She was the daughter of a lawyer, and was born at Cambridge Port, Massachusetts, on the 23rd of May 1810. Her father undertook to educate her himself; and finding her a willing and an able scholar, he crammed her with learning, early and late, in season and out of season. Her intellect became preternaturally developed, to the life-long cost of her health. By day, she was shewn about as a youthful prodigy; and by night, she was a somnambulist, and a prey to spectral illusions and nightmare. As she advanced into womanhood, she pursued her studies with incessant energy. 'Very early I knew,' she once wrote, 'that the only object in life is to grow.' She learned German, and made an intimate acquaintance with the writings of Goethe, which she passionately admired. Her father died in 1835, leaving her no fortune, and to maintain herself, she turned schoolmistress. Her reputation for learning, and for extraordinary eloquence in conversation, had become widely diffused in and around Boston, and her acquaintance was sought by most people with any literary pretensions. About this time, she was introduced to Mr. Emerson, who describes her as rather under the middle height, with fair complexion and fair strong hair, of extreme plainness, with a trick of perpetually opening and shutting her eyelids, and a nasal tone of voice. She made a disagreeable impression on most persons, including those who subsequently became her best friends; and to such an extreme, that they did not wish to be in the same room with her. This was partly the effect of her manners, which expressed an overweening sense of power, and slight esteem of others, and partly the prejudice of her fame, for she had many jealous rivals. She was a wonderful mimic, and could send children into ecstasies with her impersonations; but to this faculty she joined a dangerous repute for satire, which made her a terror to grown people. 'The men thought she carried too many guns, and the women did not like one who despised them.' Mr. Emerson, at their first meeting, was repelled. 'We shall never get far,' said he to himself, but he was mistaken. Her appearance, unlike that of many people, was the worst of Miss Fuller. Her faults and weaknesses were all superficial, and obvious to the most casual observer. They dwindled, or were lost sight of, in fuller knowledge. When the first repulse was over, she revealed new excellences every day to those who happily made her their friend. 'The day was never long enough,' says Mr. Emerson, 'to exhaust her opulent memory; and I, who knew her intimately for ten years-from July 1836 to August 1846-never saw her without surprise at her new powers. She was an active, inspiring companion and correspondent. All the art, the thought, and the nobleness in New England, seemed related to her and she to them.' The expression of her self-complacency was startling in its thoroughness and frankness. She spoke in the quietest manner of the girls she had formed, the young men who owed everything to her, and the fine companions she had long ago exhausted. In the coolest way she said to her friends: 'I now know all the people worth knowing in America, and I find no intellect comparable to my own!' Some, who felt most offence at these arrogant displays, were yet, on further reflection, compelled to admit, that if boastful, they were at any rate not far from true. Her sympathies were manifold, and wonderfully subtle and delicate; and young and old resorted to her for confession, comfort, and counsel. Her influence was indeed powerful and far-reaching. She was no flatterer. With an absolute truthfulness, she spoke out her heart to all her confidents, and from her lips they heard their faults recited with submission, and received advice as though from an oracle. It was in conversation that Miss Fuller shone. She would enter a party, and commence talking to a neighbour. Gradually, listeners would collect around her until the whole room became her audience. On such occasions she is said to have discoursed as one inspired; and her face, lighted up with feeling and intellect, dissolved its plainness, if not deformity, in beauty of expression. Some of her friends turned this faculty to account, by opening a conversation-class in Boston in 1839, over which Miss Fuller presided. She opened the proceedings with an extempore address, after which discussion followed. The class was attended by some of the most intellectual women of the American Athens, and very favourable memories are preserved of the grace and ability with which the president did her share of duty. Much of Miss Fuller's freedom and force of utterance deserted her when she essayed to write, and her friends protest against her papers being regarded as any fair index of her powers. She edited for two years The Dial, a quarterly given to the discussion of transcendental and recondite themes, and then resigned her office to Mr. Emerson. In 1844, she removed to New York, and accepted service as literary reviewer to the New York Tribune; a post for which she was singularly unfitted. The hack-writer of the daily press is always ready to spin a column or two on any new book on instant notice, but Miss Fuller could only write in ample leisure, and when in a proper mood, which mood had often to be waited for through several days. Happily, Mr. Horace Greeley, the editor of the Tribune, appreciated the genius of the reviewer, and allowed her to work in her own way. In 1846, an opportunity occurred for a visit to Europe, long an object of desire; and after a tour through England, Scotland, and France, she made a prolonged stay in Italy, and in December 1847, she was married to Count Ossoli, a poor Roman noble, attached to the papal household. Concerning him she wrote to her mother: 'He is not in any respect such a person as people in general expect to find with me. He had no instructor except an old priest, who entirely neglected his education; and of all that is contained in books he is absolutely ignorant, and he has no enthusiasm. On the other hand, he has excellent practical sense; has been a judicious observer of all that has passed before his eyes; has a nice sense of duty, a very sweet temper, and great native refinement. His love for me has been unswerving and most tender.' The conjunction of the intellectual Yankee woman with the slow Roman noble, utterly destitute of that culture which she had set above all price, seemed to many as odd as inexplicable. It was only another illustration of the saying, that extremes meet; and those who know how impossible it is for books and the proudest fame to fill a woman's heart (and Margaret Fuller had a great and very tender heart), will not wonder that she felt a strange and happy peace in Ossoli's simple love. She was a friend of Mazzini's, and when, in 1848, revolution convulsed almost every kingdom on the continent, she rejoiced that Italy's day of redemption had at last dawned. During the siege of Rome by the French, she acted as a hospital nurse, and her courage and activity inspired extraordinary admiration among the Italians. When Rome fell, her hopes for her chosen country vanished, and she resolved to return to America. 'Beware of the sea!' had been the warning of a fortune-teller to Ossoli when a boy. In spite of gloomy forebodings, they set sail from Leghorn in a merchant-ship. At the outset of the voyage, the captain sickened and died of confluent small-pox in its most malignant form. Ossoli was next seized, and then their infant boy, but both recovered, though their lives were despaired of. At last the coast of America was reached, when, on the very morning of the day they would have landed, 16th July 1849, the ship struck on Fire Island beach. For twelve hours, during which the vessel went to pieces, they faced death. At last crew and passengers were engulfed in the waves, only one or two reaching the land alive. The bodies of Ossoli and his wife were never found, but their child was washed ashore, and carried to Margaret's sorrowing mother. DE BERANGERNotwithstanding the 'De' prefixed to his name, the illustrious French songster was of the humblest origin. In youth, the natural energies of his intellect led him to authorship; but he was at first like to starve by it, and had at one moment serious thoughts of enlisting as a soldier in the expedition to Egypt, when he was succoured by the generosity of Lucien Bonaparte, who conferred on him the income he was entitled to as a member of the Institute. It was not without cause, and a cause honourable to his feelings, that Beranger was ever after a zealous Bonapartist. Beranger is, without doubt, the most popular poet of France: men of literature, citizens, workmen, peasants, everybody, in fact, sings his songs. Yet his modesty was never spoiled by flattery; when a professor of high standing spoke in his presence of his 'immortal works;' he replied: 'My dear friend, I believe really that I am over praised; permit ma to doubt the immortality of my poems. At the opening of my career, the French song had no other pretension than to enliven a dessert. I asked if it would not be possible to raise its tone, and use it as the interpreter of the ideas and feelings of a generous nation. At a dinner given by M. Laffitte, where Benjamin Constant was present, I sang one of my first songs, when the latter declared that a new horizon was opened to poetry. This encouraged me to persevere.' The circumstances of the times favoured the poet; he never ceased to sing the glories of France, and particularly of the Empire. Yet he is most truly himself in those little dramas, where, placing a single person on the scene, he expresses the national feeling, such as Le Vieux Sergent, Le Roi, d'Ivetöt; whilst he was said to be the only man who knew how to make riches popular, he had another secret, how to render his own poverty almost as inexhaustible in kindnesses as the rich. He never would receive anything, and lived to the last on the profits of his works, leaving his small fortune to be divided among a few poor and old friends. ROYAL VISIT TO MERCHANT TAILORS' HALLOn the 16th of July 1607, James I, accompanied by Henry, Prince of Wales, visited the Merchant Tailors' Company of London, at their hall, in Threadneedle Street. The records of the company contain several interesting notices of this royal visit. A short time previous to its taking place, a meeting was held to consult how the king could be best entertained; and Alderman Sir John Swynnerton was entreated 'to confer with Mr. Benjamin Jenson, the poet, about a speech to be made to welcome his majesty, and for music, and other inventions.' From the same source we also glean the following account of the entertainment: At the upper end of the hall, there was a chair of estate, where his majesty sat; and a very proper child, well-spoken, being clothed like an Angel of Gladness, with a taper of frankincense burning in his hand, delivered a short speech, containing eighteen verses, devised by Mr. Ben. Jonson, which pleased his majesty marvellously well. And upon either side of the hall, in the windows near the upper end, were galleries made for music, in either of which were seven singular choice musicians, playing on their lutes, and in the ship, which did hang aloft in the hall, were three rare men and very skilful, who sung to his majesty; wherein it is to be remembered, that the multitude and noise was so great, that the lutes and songs could scarcely be heard or understood. And then his majesty went up into the king's chamber, where he dined alone at a table which was provided only for his majesty, in which chamber were placed a very rich pair of organs, whereupon Mr. John Bull, doctor of music, and brother of this company, did play all the dinner-time. After dinner, James was presented with a purse of gold; but on being shewn a list of the eight kings, and other great men, who had been members of the company, he declined to add his name to it; stating that he already belonged to another guild, but that his son, the Prince of Wales, should at once become a Merchant Tailor. Then all descended to the great hall, where the prince, having dined, was presented with a purse of gold, and the garland being put on his head, he was made free of the company amidst loud acclamations of joy. During this ceremony, the king stood in a new window made for the purpose, 'beholding all with a gracious kingly aspect.' 'After all which, his majesty came down to the great hall, and sitting in his chair of estate, did hear a melodious song of farewell by the three rare men in the ship, being apparelled in watchet silk, like seamen, which song so pleased his majesty, that he caused it to be sung three times over.' MOCK-ELECTION IN THE KING'S BENCHIn the old bad system of imprisonment for debt, there were many evils, but none worse than the enforced idleness undergone by the prisoners. It is easy to understand how a man who had been long kept in prison came out a worse member of society than he went in. The sufferers, in general, made wonderful struggles to get their time filled up, though it was too often with things little calculated for their benefit. Sometimes special amusements were got up amongst them. In 1827, the inmates of the King's Bench Prison, in London, devised one of such a nature, that public attention was attracted by it. It was proposed that they should elect a member to represent 'Tenterden' (a slang name for the prison) in parliament. Three candidates were put up, one of whom was Lieutenant Meredith, an eccentric naval officer. All the characteristics of a regular election were burlesqued. Addresses from the candidates to the 'worthy and independent electors' were printed and placarded about the walls of the prison; squibs were written, and songs sung, disparaging the contending parties; processions were organised with flags, trappings, and music, to take the several candidates to visit the several 'Collegians' (i. e., prisoners) in their rooms; speeches were made in the courtyards, full of grotesque humour; a high-sheriff and other officers were chosen to conduct the proceedings in a dignified way; and the electors were invited to 'rush to the poll' early on Monday morning, the 16th of July. The turnkeys of the prison entered into the fun. While these preliminary plans were engaging attention, a creditor happened to enter the prison; and seeing the prisoners so exceedingly joyous, declared that such a kind of imprisonment for debt could be no punishment; and he therefore liberated his debtor. Whether owing to this singular result of prison-discipline (or indiscipline), or an apprehension of evils that might follow, Mr. Jones, marshal of the prison, stopped the whole proceedings on the morning of the 16th. This, however, he did in so violent and injudicious a way as to exasperate the whole of the prisoners-some of whom, although debtors, were still men of education and self-respect. They resented the language used towards them, and the treatment to which they were subjected; until at length a squad of Foot-guards, with fixed bayonets, forcibly drove some of the leaders into a filthy 'black-hole' or place of confinement. The matter caused a few days' further excitement, both within and without the prison; and it was generally thought that a more good-Humoured course of proceeding on the part of the marshal would have brought the whole affair to a better ending. AN APPLE-STALL DISCUSSED IN PARLIAMENTA case which attracted some notice and created some amusement in 1851, serves, although trifling in itself, to illustrate the tenacity with which rights of any kind are maintained in England. During a period of several years, strollers in Hyde Park, particularly children, were familiar with the 'White Cottage,' a small structure near the east end of the Serpentine, at the junction of several footpaths. In this cottage Ann Hicks dispensed apples, nuts, gingerbread, cakes, ginger-beer, &c. It had grown up from a mere open stall to something like a small tenement, simply through the pertinacious applications of the stall-keeper to persons in office. Until 1843, there was an old conduit at that spot, once connected with a miniature water-fall, but occupied then by Ann Hicks for the purposes of her small dealings. This was pulled down, and her establishment was reduced to a mere open stall. Ann Hicks, who appears to have been an apt letter-writer, wrote to Lord Lincoln, at that time Chief Commissioner of Woods and Forests, stating that her stall consisted merely of a table with a canvas awning, and begging for permission to have some kind of lock-up into which she could place her wares at night. She was therefore allowed to make some such wooden erection as those which have long existed near the Spring Garden corner of St. James' Park. She wrote again, after a time, begging for a very small brick enclosure, as being more secure at night than one of wood; this was unwillingly granted, because quite contrary to the general arrangements for the management of the park; but as she was importunate, and persuaded other persons to support her appeal, permission was given. Ann Hicks put a wide interpretation on this kindness, for she not only built a little brick room, but she built a little window as well as a little door to it. She wrote again, saying that her locker was not large enough; might she make it a little higher, to afford space for her ginger-beer bottles? Yes, provided the total height did not exceed five feet. She wrote again, might she repair the roof, which was becoming leaky? Obtaining permission, she not only repaired the roof, but protruded a little brick chimney through it; and advancing still further, she made a little brick fireplace, whereon she could conduct small cooking operations. She wrote again, stating that the boys annoyed her by looking in at the little window: might she put up a few hurdles, to keep them at a distance? This being allowed, she gradually moved the hurdles further and further outwards, till she had enclosed a little garden. Thus the open stall developed into a miniature tenement. Lord Seymour came into office as chief-commissioner in 1850, and found that Ann Hicks had given the officials as much trouble as if she had been a person of the first consequence. Preparations were at that time being made for the great Exhibition of 1851, and it was deemed proper to remove obstructions as much as possible from the Park. Ann Hicks was requested to remove the white cottage. She flatly refused, asserting that the ground was her own by vested right. She told a story to the effect that, about a hundred years earlier, her grandfather had saved George II from peril in the Serpentine; that, as a reward, he had obtained permission to hold a permanent stall in the park; that he had held this during a long life, and then his son, and then Ann Hicks; and that she had incurred an expenditure of £130 in building the white cottage. After due inquiry, no evidence could be found other than that Ann Hicks had long had a stall in that spot. Lord Seymour, wishing to be on the right side, applied to the Duke of Wellington, as ranger of Hyde Park; and the veteran, punctual and precise in small matters as in great, caused the whole matter to be investigated by a solicitor. The result was that Ann Hicks's story was utterly discredited, and she was ordered to remove-receiving, at the same time, a small allowance for twelve months as a recompense. She resisted to the last, and became a source of perpetual annoyance to every one connected with the park. When the cottage was removed, and the money paid, she placarded the trees in the park with accusations against the commissioners for robbing her of her rights. She pestered noblemen and members of parliament to intercede in her favour, and even wrote to the Queen. She gradually gave up the pretended vested right, and put in a claim for mere charity. Nevertheless, in July of the following year, when the Exhibition was open, the case was brought before parliament by Mr. Bernal Osborne. Full explanations were given by the government, and the agitation died out. Many foreigners were in England at the time, and the matter afforded them rather a striking proof of the jealousy with which the nation regards any supposed infractions by the government of the rights of private persons-even to so small a matter as an apple-stall. OLD SUBURBAN TEA-GARDENSLondon has so steadily enlarged on all sides, and notably so within the present century, that the old suburbs are embraced in new streets; and a comparatively young person may look in vain for the fields of his youthful days. 'The march of brick and mortar' has invaded them, and the quiet country tea-garden to which the Londoner wended across grass, may now be transformed to a glaring gin-palace in the midst of a busy trading thorough-fare. Readers of our old dramatic literature may be amused with the rustic character which invests the residents of that portion of the outskirts of old London comprehended between King's Cross and St. John's Wood, as they are depicted by Ben Jonson in his Tale of a Tub. The action of the drama takes place in St. Pancras Fields, the country near Kentish Town, Tottenham Court, and Marylebone. The dramatis persona seem as innocent of London and its manners as if they were inhabiting Berkshire, and talk a broad-country dialect. This northern side of London preserved its pastoral character until a comparatively recent time, it being not more than twenty years since some of the marks used by the Finsbury archers of the days of Charles II, remained in the Shepherd and Shepherdess Fields, between the Regent's Canal and Islington. From White Conduit House, the view was unobstructed over fields to Highgate. The pretorium of a Roman camp was visible where Barnsbury Terrace now stands; the remains of another, as described by Stukely, was situated opposite old St. Pancras Church; and hordes of cows grazed where the Euston Square terminus of our great midland railway is now placed, and which was then Rhodes' Farm.  At the commencement of the present century, the country was open from the back of the British Museum to Kentish Town; the New Road, from Tottenham to Battle-bridge, was considered unsafe after dark; and parties used to collect at stated points to take the chance of the escort of the watchman in his half-hour round. Hampstead and Highgate could only be reached by 'short stages,' going twice a day; and a journey there, once or twice in the summer, was the furthest and most ambitious expedition of a Cockney's year. Both villages abounded in inns, with large gardens in their rear, overlooking the pleasant country fields towards Harrow, or the extensive and more open land towards St. Alban's and the valley of the Thames. 'Jack Straw's Castle' and 'The Spaniards' still remain as samples of these old 'rural delights.' The features of the latter place, as they existed more than a century since, have been preserved by Chatelaine, in a small engraving he executed about 1745, and which we here copy. The formal arrangement of trees and turf; in humble imitation of the Dutch taste introduced by William III, and exhibited at Hampton Court and Kensington palaces, may be noted in this humbler garden. For those who cared not for such distant pleasures, and who could not spare time and money to climb the hills that bounded the Londoner's northern horizon, there were 'Arcadian bowers' almost beneath the city walls. Following the unfragrant Fleet ditch until it became a comparatively clear stream in the fields beyond Clerkenwell, the citizen found many other wells, each within its own shady garden. The Fleet was anciently known as 'the river of wells,' from the abundance of these rills, which were situated on its sloping banks, and swelled its tiny stream. 'The London Spa' gave the name to the district now known as Spa-fields, Rosomon's Row being built on its site. The only representation of the gardens occurs in the frontispiece to an exceedingly rare pamphlet, published in 1720, entitled May-day, or the Origin of Garlands, which appears to be an elaborate puff for the establishment, as we are told in grandiloquent rhymes: Now ninepin alleys and now skittles grace The late forlorn, sad, desolated place; Arbours of jasmine, fragrant shades compose, And numerous blended companies enclose. The spring is gratefully adorn'd with rails, Whose fame shall last till the New River fails! Situated in the low land near by (sometimes termed Bagnigge Marsh), was a well and its pleasure-grounds, known as 'Black Mary's Hole.' Spring Place, adjoining Exmouth Street, marks its locality now; it obtained its name from a black woman named Mary Woolaston, who rented it in the days of Charles II. Another 'hole,' of worse repute, was in the immediate vicinity, and is better known to the reader of London literature as 'Hockley-in-the-Hole.' There assembled on Sundays and holidays the Smithfield butchers, the knackers of Turnmill Street, and the less respectable denizens of Field Lane, for dog-fights and pugilistic encounters. 'That men may be instructed by brutes, Æsop, Lemuel Gulliver, and Hockley-in-the-Hole, shew us,' says the author of The Taste of the Town, 1731; adding, with satiric slyness: 'Who can view dogs tearing bulls, bulls goring dogs, or mastiffs throttling bears, without being animated with their daring spirits.' It became the very type of low blackguardism, and was abolished by the magistracy at the close of the last century. A short distance further north, in the midst of ground encircled by the Fleet River, stood the more famous Bagnigge Wells, long the favoured resort of Londoners, as it added the attraction of a concert-room to the pleasure of a garden. The house was traditionally said to have been a country residence of Nell Gwynn, the celebrated mistress of Charles II; and her bust was consequently placed in the post of honour, in the Long Room, where the concerts were given. The house was opened for public reception about the year 1757, in consequence of the discovery, by Mr. Hughes, of two mineral springs (one chalybeate, the other cathartic), which had been covered over, but by their percolation, injured his favourite flower-beds. Mineral waters being then much sought after, he took advantage of his springs, and opened his gardens to the public with much success. In The Shrubs of Parnassus, 1760, is a curious poetical description of the company usually seen: Here ambulates th' Attorney, looking grave, And Rake, from Bacchanalian rout uprose, And mad festivity. Here, too, the Cit, With belly turtle-stuffed, and Man of Gout With leg of size enormous. Hobbling on, The pump-room he salutes, and in the chair He squats himself unwieldy. Much he drinks, And much he laughs, to see the females quaff The friendly beverage.  There is a pleasing mezzotint engraving (now very scarce), which was published by the great printseller of the day, Carington Bowles, in St. Paul's Churchyard, 1780, depicting two fair visitors to the gardens, breaking through the laws against plucking flowers. It is entitled, 'A Bagnigge Wells Scene, or no resisting Temptation.' It is copied above. The gardens at that time were extensive, and laid out in the old-fashioned manner, with clipped trees, walks in formal lines, and a profusion of leaden statues. A fountain was placed in the centre, as shewn in our cut. A Dutch Cupid half-choking a swan was the brilliant idea it shadowed forth. The roof of the temple is seen above the trees to the left; it was a circular domed colonnade, formed by a double row of pillars and pilasters; in its centre was a double pump, one piston supplying the chalybeate, the other the cathartic water; it was encircled by a low balustrade. A grotto was the other great feature of the garden; it was a little castellated building of irregular hexagonal form, covered with shells, stones, glass, &c., forming two apartments open to the gardens. The waters were drunk for the charge of threepence each person, or delivered from the pump-room at eight-pence per gallon. As a noted place for tea-drinking, it is frequently alluded to by authors of the last century. In the prologue to Colman's comedy, Bon Ton, 1776, a vulgar city-madam from Spitalfields thus defines that phrase: Bone Tone's the space twix't Saturday and Monday, And riding in a one-horse chair on Sunday. 'Tis drinking tea on summer afternoons At Bagnigge Wells with china and gilt spoons. There is a print of the company in the great room, styled, 'The Bread and Butter Manufactory, or the Humours of Bagnigge Wells.' Miss Edgeworth alludes to it in one of her tales as a place of vulgar resort; and a writer of 1780 says: The Cits to Bagnigge Wells repair, To swallow dust, and call it air. The gardens were much curtailed in 1813, when the bankruptcy of the proprietors compelled a general sale on the premises. They gradually sank in repute; the Long-room was devoted to threepenny concerts; and the whole was ultimately destroyed in 1841, when a public-house was erected on the site of the old tavern. A relic of the oldest house remained over a side-door at the end of the garden, consisting of a head in high-relief, and an inscription: 'S. T. This is Bagnigge House neare the Finder a Wakefeilde. 1680.' The latter was the sign of another house of entertainment in Gray's Inn Lane; and nearly opposite to it, within a short distance of King's Cross, was another garden, where St. Chad's Well offered its cure to invalids. The New Underground Railway cuts through the whole of this marshy district, once so redolent of healing springs, and to which we may bid adieu in the grandiloquent words of the author quoted above: 'Farewell, sweet vale! how much dost thou excel Arno or Andalusia'  Passing along the great main-road to Islington from Smithfield (St. John Street Road), we find on the banks of the New River, at that point where it crosses the road, a theatre still bearing the name of Sadler's Wells, and occupying the site of that old sanatorium. The aspect of the house in 1745 is shewn in our engraving, from a view published at that period. The reader who is familiar with the works of Hogarth, will recognise the entrance-gate and portion of the house in the background to his print of 'Evening,' one of the 'Four Times of the Day.' The well was a medicinal spring, once the property of the monks of Clerkenwell, reputed for its cures before the dissolution of the priory in Henry VIII's reign, when this well was ordered to be stopped up as a relic of superstition. In the reign of Charles II, the house and grounds were in the hands of a surveyor of the highway named Sadler, who employed men to dig gravel in his garden, leading to the rediscovery of the well under an arch of stone. This happened in 1683. With great business tact, Mr. Sadler engaged a certain 'T.G., Doctor of Physick,' to write 'A True and Exact Account of Sadler's Well; or, the New Mineral Waters lately found at Islington,' in which it was recommended as equal in virtue to that of Tunbridge. He built a music-house, and succeeded in making it 'so frequented, that there are five or six hundred people there constantly every morning.' After a few years, that attraction ceased; but as a place of amusement, it never failed in popularity. In 1690, it was known as Miles's Music-house; to him succeeded Francis Forcer, the son of a musician, who introduced rope-dancers, tumblers, &c., for the public amusement; no charge was made for this, but only paid for in the drink visitors ordered. While under these managements, the premises appear to have been a tea-garden with a music-room, on the plan of Bagnigge Wells; but in 1765, one Rosoman, an eminent builder, took the lease, pulled down the old building, and erected a theatre on the site. Opposite to the Wells, on the south side of the New River, was another favourite tea-garden, 'The Sir Hugh Middleton,' which still exists as an ordinary public-house, minus the garden. In Hogarth's print, already alluded to, it appears as a country hostel, with a luxuriant vine trained over its wooden front; the scenery beyond is a Cockney arcadia, with milk-maids and cows, open fields and farm-tenements, to the Middlesex alps at Highgate.  Turning round the New River head, 'Merlin's Cave,' another tea-garden, wooed the traveller; but if he resolutely crossed the New Road, he came to White Conduit House, on the extreme verge of London, situated on the high land just above the tunnel connecting the Regent's and Paddington canals. It took its name from the contiguous conduit originally constructed for the use of the Charter-house, and once bore the initials of Thomas Sutton, its founder, and the date 1641. Our cut represents the aspect of both buildings, as they stood in 1827. The Conduit was then in a pitiable state of neglect-denuded of the outer case of stone, a mere core of rubble; the house was a low-roofed building, with a row of clipped trees in front, and a large garden in the rear, well supplied with arbours all round for tea-drinking; and such was its popularity at the commencement of this century, that fifty pounds was often taken on a Sunday afternoon for sixpenny tea-tickets. Its bread was as popular as the buns of Chelsea; and 'White Conduit loaves' was a London cry, listened for by such old ladies as wished to furnish a tea-table luxury to their friends. On week-days, it was a kind of minor Vauxhall, with singing and fire-works; on great occasions, the ascent of a balloon crowded the gardens, and collected thousands of persons in the fields around. It was usual for London 'roughs' to assemble in large numbers in these fields for foot-ball play on Easter Monday; occasionally 'the fun' was diversified by Irish faction-fights; the whole neighbourhood is now covered with houses. The old tea-garden built upon; and the house destroyed in 1849; a large public-house now marking the site of the older building we engrave. Field-paths, with uninterrupted views over the country, led toward St. Pancras, where another well and public garden invited strollers with its sanitary promises. The way between this place and London was particularly unsafe to pedestrians after dark, and robberies between here and Gray's Inn Lane were common in the early part of the last century. About half a mile to the west, the Jew's Harp Tavern invited wayfarers to Primrose Hill, being situated close to the south of the present Regent's Park Barracks. Marylebone Gardens was the most important of these north-western places of amusement. It was situated opposite the old parish church, on ground now covered by Devonshire Street and Beaumont Street. It is mentioned by Pepys, two years after the great fire of London, as 'a pretty place' to walk in. Its bowling-alleys were famous, and here Sheffield, Duke of Buckingham, 'bowled time away' in the days of Pope and Gay. The latter author alludes to this place more than once in the Beggar's Opera, as a rendezvous for the dissipated, putting it on a level with one of bad repute already mentioned. He alludes to the dog-fights allowed here in one of his Fables: Both Hockley-hole and Marybone The combats of my dog have known. After 1740, it became more respectable-a shilling was charged for admission, an orchestra was erected; the gardens were occasionally illuminated, fetes given, and a rivalry to Vauxhall attempted, which achieved a certain amount of success. Balls and concerts were given; Handel's music was played under Dr. Arne's direction; Chatterton wrote a burlesque burletta after the fashion of Midas, entitled The Revenge, which was performed in 1770; but after many vicissitudes, the gardens were closed within the next eight years, and the site turned to more useful purposes. Pursuing the road toward Paddington, 'The Yorkshire Stingo,' opposite Lisson Grove, invited the wayfarer to its tea-garden and bowling-green; it was much crowded on Sundays, when an admission fee of sixpence was demanded at the doors. For that a ticket was given, to be exchanged with the waiters for its value in refreshments; a plan very constantly adopted in these gardens, to prevent the intrusion of the lowest classes, or of such as might only stroll about them without spending anything. The Edgeware Road would point the way to Kilburn Wells, which an advertisement of 1773 assures us were then 'in the utmost perfection, the gardens enlarged and greatly improved, the great room being particularly adapted to the use and amusement of the politest companies, fit for either music, dancing, or entertainment.' The south-western suburb had also its places of resort. 'Cromwell Gardens,' and 'The Hoop and Toy,' at Brompton; 'The Fun,' at Pimlico, celebrated for its ale; 'The Monster,' and 'Jenny's Whim,' in the fields near Chelsea. Walpole, in one of his letters, says that at Vauxhall he 'picked up Lord Granby, arrived very drunk from Jenny's Whim.' Angelo, in his Pic-nix or Table-talk, describes it as 'a tea-garden, situated, after passing a wooden bridge on the left, previous to entering the long avenue, the coach-way to where Ranelagh once stood.' This place was much frequented from its novelty, being an inducement to allure the curious by its amusing deceptions, particularly on their first appearance there. Here was a large garden, in different parts of which were recesses; and treading on a spring, taking you by surprise, up started different figures, some ugly enough to frighten you; like a Harlequin, Mother Shipton, or some terrific animal. In a large piece of water, facing the tea-alcoves, large fish or mermaids were spewing themselves above the surface. This queer spectacle was kept by a famous mechanist, who had been employed at one of the winter theatres.' The water served less reputable purposes in 1755, when, according to a notice in The Connoisseur, it was devoted to 'the royal diversion of duck-hunting.'  This disgraceful 'diversion' gave celebrity to a house in St. George's Fields, which took for its sign 'The Dog and Duck,' though originally known as 'St. George's Spa.' It was established, like so many of these places, after the discovery of a mineral spring, about the middle of the last century. 'As a public tea-garden,' says a writer in 1813, 'it was within a few years past a favourite resort of the vilest dregs of society, until properly suppressed by the magistrates.' The site forms part of the ground upon which the great lunatic asylum, known as New Bethlehem Hospital, now stands; and in the boundary-wall is still to be seen the sculptured figure of a seated dog holding a duck in his mouth, which once formed the sign of the tea-garden. The 'sport' consisted in hunting unfortunate ducks in a pond by dogs; the diving of the one, and the pursuit of the others, gratifying the brutal spectators, who were allowed to bring their dogs to 'the hunt,' on the payment of six-pence each; the owner of the dog who caught and killed the duck might claim that prize. Closer to London, but on the same side of the Thames, was Lambeth Wells, where concerts were occasionally given; 'The Apollo Gardens' (on the site of Maudsley's factory, in the Westminster Road), with an orchestra in its centre, and alcoves for tea-drinking, the walls of which were covered with pictures-a very common decoration to the wooden boxes in all these gardens, giving amusement to visitors in examining them. 'Cuper's Gardens' were opposite Somerset House, the present Waterloo Bridge Road running over what was once its centre. They were called after the original proprietor, a gardener, named Boydell Caper, who had been in the service of the famous collector, Thomas, Earl of Arundel, whose antique marbles are still at Oxford. Cuper begged from him such as were mutilated, and stuck them about his walks. In 1736, an orchestra was added to its attractions; it subsequently became famed for its fireworks; but ultimately most so for the loose society it harboured, and for which it was deprived of its licence in 1753. In addition to these the inhabitants of Southwark might disport in 'Finch's Grotto,' situated in Gravel Lane, Southwark; 'The Jamaica Tavern,' or 'St Helena Gardens,' Rotherhithe; so that London was literally surrounded with these popular places of resort; as alluded to by the Prussian D'Archenholz, who, in his account of England (published toward the close of the last century), observes: 'The English take a great delight in the public gardens, near the metropolis, where they assemble and drink tea together in the open air. The number of these in the neighbourhood of the capital is amazing, and the order, regularity, neatness, and even elegance of them are truly admirable. They are, however, very rarely frequented by people of fashion; but the middle and lower ranks go there often, and seem much delighted with the music of an organ, which is usually played in an adjoining building.' Now, owing to the altered tastes of the age, scarcely one of them exists, and they will be remembered only in the pages of the topographer. |