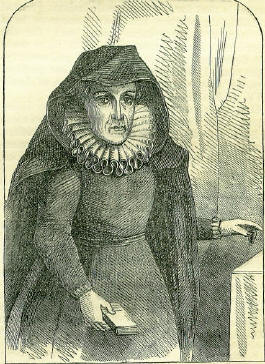

13th JulyBorn: Regnier de Graaf, 1641, Schoenhaven, in Holland; Richard Cumberland, bishop of Peterborough, 1632. Died: Pope John III, 573; Emperor Henry II, 1024; Du Guesclin, constable of France, illustrious warrior, 1380, Chäteauneuf-Randon; Sir William Berkley, 1677, Twickenham; Richard Cromwell, ex-Protector of the three kingdoms, 1712, Cheshunt; Elijah Fenton, poet, 1730, Easthampstead; Bishop John Conybeare, 1758, Bristol; Dr. James Bradley, astronomer, 1762; Rev. John Lingard, author of a History of England, 1851, Hornby, near Lancaster. Feast Day: St. Anacletus, martyr, 2nd century; St. Eugenius, bishop of Carthage, and his companions, martyrs, 505; St. Turiaf, Turiave or Thivisiau, bishop of Doi, in Brittany, about 749. FESTIVAL OF MIRACLESThis day (July 13th), if Sunday, or the first Sunday after the 13th, begins the festival of the Miracles at Brussels, which lasts for fifteen days. The first day, Sunday, however, is the grand day of celebration; for on this takes place the public procession of the Holy Sacrament of the Miracles. We had an opportunity of witnessing this locally celebrated affair on Sunday, July 15th, 1860, and next day procured from one of the ecclesiastical officials a historical account of the festival, of which we offer an abridgment. In the year 1369, there lived at Enghein, in Hainault, a rich Jew, named Jonathan, who, for purposes of profanation, desired to procure some consecrated wafers. In this object he was assisted by another Jew, named Jean de Louvain, who resided in Brussels, and had hypocritically renounced Judaism. Jean was poor, and in the hope of reward gladly undertook to steal some of the wafers from one of the churches. After examination, he found that the church of St. Catherine, at Brussels, offered the best opportunity for the theft. Gaining access by a window on a dark night in October, he secured and carried off the pix containing the consecrated wafers; and the whole were handed to Jonathan, who gave his appointed reward. Jonathan did not long survive this act of sacrilege. He was assassinated in his garden, and his murderers remained unknown. After his death, his widow gave the pix, with the wafers, to a body of Jews in Brussels, who, in hatred of Christianity, were anxious to do the utmost indignity to the wafers. The day they selected for the purpose was Good Friday, 1370. On that day, meeting in their synagogue, they spread the holy wafers, sixteen in number, on a table, and with horrid imprecations proceeded to stab them with poniards. To their amazement, the wounded wafers spouted out blood, and in consternation they fled from the spot! Anxious to rid themselves of objects on which so very extraordinary a miracle had been wrought, these wicked Jews engaged a woman, named Catherine, to carry the wafers to Cologne, though what she was to do with them there is not mentioned. Catherine fulfilled her engagement, but with an oppressed conscience she, on her return, went and revealed all to the rector of the parish church. The Jews concerned in the sacrilege were forthwith brought to justice. They were condemned to be burned, and their execution took place May 22nd, 1370. Three of the wafers were restored to the clergy of St. Guduli, where they have ever since remained as objects of extreme veneration. On several occasions they have good service to the inhabitants of Brussels, in the way of stopping epidemics. On being appealed to by a solemn procession in 1529, a grievous epidemic at once ceased. From 1579 to 1585, during certain political troubles in the Netherlands, there were no processions in their honour; and they were similarly neglected for some years after the great revolution of 1789-92. But since Sunday, July 14th, 1804, the annual procession has been resumed, and the three wafers shewing the miraculous marks of blood, have been exposed to the adoration of the faithful in the church of St. Guduli. It is added in the authoritative account, that certain indulgences are granted by order of Pius VI. to all who take part in the procession, and repeat daily throughout the year, praises and thanks for the most holy sacrament of the Miracles. In the openings of the pillars along both sides of the choir of St. Guduli, is suspended a series of Gobelin tapestries, vividly representing the chief incidents in the history of the Miracles, including the scene of stabbing the wafers. BERTRAND DU GUESCLINThis flower of French chivalry was of a noble but poor family in Brittany. 'Never was there so bad a boy in the world,' said his mother, 'he is always wounded, his face disfigured, fighting or being fought; his father and I wish he were peaceably underground.' All the masters engaged to teach him, gave up the task in despair, and to the end of his life he could neither read nor write. A tourney was held one day at Rennes, to which his father went; his son, then about fourteen, secretly followed him, riding on a miserable pony: the first knight who retired from the lists found the young hero in his hostelry, who, throwing himself at his knees, besought him to lend him his horse and arms. The request was granted, and Du Guesclin, preparing in all haste, flew to the combat, and overthrew fifteen adversaries with such address and good grace as to surprise all the spectators. His father presented himself to run a course with him, but Bertrand threw down his lance. When persuaded to raise his visor, the paternal joy knew no bounds; he kissed him tenderly, and henceforward took every means to insure his advancement. His first campaign with the French army was made in 1359, where he gave full proof of his rare valour, and from that time he was the much-feared enemy of the English army, until taken prisoner by the Black Prince at the battle of Navarete, in Spain, in 1367. In spite of the repeated entreaties of both French and English nobles, the prince kept him more than a year at Bordeaux, until it was whispered that he feared his rival too much to set him free. Hearing this, Edward sent for Du Guesclin and said: 'Messire Bertrand, they pretend that I dare not give you your liberty, because I am afraid of your' 'There are those who say so,' replied the knight, 'and I feel myself much honoured by it.' The prince coloured, and desired him to name his own ransom. 'A hundred thousand florins,' was the reply. 'But where can you get so much money?' 'The king of France and Castile, the pope, and the Duke of Anjou will lend it to one, and were I in my own country, the women would earn it with their distaffs.' All were charmed with his frankness, and the Princess of Wales invited him to dinner, and offered to pay twenty thousand francs towards the ransom. Du Guesclin, kneeling before her, said: 'Madame, I believed myself to be the ugliest knight in the world, but now I need not be so displeased with myself.' Many of the English forced their purses on him, and he set off to raise the sum; but on the way he gave with such profusion to the soldiers he met that all disappeared. On reaching home, he asked his wife for a hundred thousand francs he had left with her, but she also had disposed of them to needy soldiers; this her husband approved of, and returning to the Duke of Anjou and the pope, he received from them forty thousand francs, but on his way to Bordeaux these were all disposed of, and the Prince of Wales asking if he had brought the ransom, he carelessly replied: 'That he had not a doubloon.' 'You do the magnificent!' said the prince. 'You give to everybody, and have not what will support yourself; you must go back to prison.' Du Guesclin withdrew, but at the same time a gentleman arrived from the French king prepared to pay the sum required. He was raised to the highest post in the kingdom, that of Connétable de France, in 1370, amidst the acclamations and joy of the whole nation; yet, strange to say, after all his services, he lost the confidence of the king a few years after, who listened to his traducers, and wrote a letter most offensive to the hero's fidelity. Du Guesclin immediately sent back the sword belonging to his office of Connétable; but the cry of the whole nation was in his favour. The superiority of his military talents, his generosity and modesty had extinguished the feelings of jealousy which his promotion might have created. Charles acknowledged that he had been deceived, and sent the Dukes of Anjou and Bourbon to restore the sword, and appoint him to the command of the army in Auvergne, where his old enemies the English were pillaging. He besieged the castle of Randan, and was there attacked with mortal disease, which he met with the intrepid firmness which characterised him, and with the sincere piety of a Christian. At the news of his death, the camp resounded with groans, his enemies even paying homage to his memory; for they had promised to surrender on a certain day if not relieved, and the commander marched out, followed by his garrison, and kneeling beside the bier, laid the keys upon it. The king ordered him to be buried at St. Denis, at the foot of the mausoleum prepared for himself. The funeral cortege passed through France amidst the lamentations of the people, followed by the princes of the blood, and crowds of the nobility. This modest epitaph was placed on his grave: 'Ici gist noble homme, Messire Bertrand du Guesclin, Comte de Longueville et Conne'table de France, qui trépassa au Chastel neuf de Randall le 13me Jour de Juillet 1380. Priez Dieu pour lui.' A very rare phenomenon was seen after his death-the chief place in the state was vacant, and no one would take it. The king offered it to the Sire de Couci; he excused himself', recommending Du Guesclin's brother-in-arms, De Clisson; but he and Sancerre both declared that after the grand deeds that had been wrought, they could not satisfy the king, and it was only filled up at the beginning of the following reign by Clisson accepting the dignity. RICHARD CROMWELL This day, 1712, died Richard Cromwell, eldest son of Oliver, and who, for a short time after his father (between September 3, 1658, and May 25, 1659), was acknowledged Protector of these realms. He had lived in peaceful obscurity for fifty-three years after giving up the government, and was ninety when he died. The ex-Protector, Richard, has usually been spoken of lightly for resigning without any decisive effort to maintain himself in his place; but, perhaps, it is rather to the credit of his good sense, that he retired as he did, for the spirit in which the restoration of Charles II was soon after effected, may be regarded as tolerable proof that any obstinate attempt to keep up the Cromwellian rule, would have been attended with great hazard. While it never has been, and cannot be, pretended that Richard was aught of a great man, one cannot but admit that his perfect negativeness after the Restoration, had in it something of dignity. That he could scarcely ever be induced to speak of politics, was fitting in one who had been at the summit of state, and found all vanity and instability. There was, moreover, a profound humour under his external negativeness. His conduct in respect of the addresses which had come to him during his short rule, was not that of a common-place character. When obliged to leave Whitehall, he carried these documents with him in a large hair-covered trunk, of which he requested his servants to take particular care. Why so much care of an old trunk?' inquired some one; 'what on earth is in it?' 'Nothing less,' quoth Richard, 'than the lives and fortunes of all the good people of England.' Long after, he kept up the same joke, and even made it a standing subject of mirth among his friends. Two new neighbours, being introduced to his house, were very hospitably entertained in the usual manner, along with some others, till the company having become merry, Richard started up with a candle in his hand, desiring all the rest to follow him. The party proceeded with bottles and glasses in hand, to the garret, where, somewhat to the surprise of the new guests, who alone were uninitiated, the ex-Protector pulled out an old hairy trunk to the middle of the floor, and seating himself on it, proposed as a toast, 'Prosperity to Old England.' Each man in succession seated himself on the trunk, and drank the toast; one of the new guests coming last, to whom Mr. Cromwell called out: 'Now, sit light, for you have the lives and fortunes of all the good people of England under you.' Finally, he explained the freak by taking out the addresses, and reading some of them, amidst the laughter of the company. SUPERSTITIONS, SAYINGS, &c., CONCERNING DEATHIf a grave is open on Sunday, there will be another dug in the week. This I believe to be a very narrowly limited superstition, as Sunday is generally a favourite day for funerals among the poor. I have, however, met with it in one parish, where Sunday funerals are the exception, and I recollect one instance in particular. A woman coming down from church, and observing an open grave, remarked: 'Ah, there will be some-body else wanting a grave before the week is out!' Strangely enough (the population of the place was then under a thousand), her words came true, and the grave was dug for her. If a corpse does not stiffen after death, or if the rigor mortis disappears before burial, it is a sign that there will be a death in the family before the end of the year. In the case of a child of my own, every joint of the corpse was as flexible as in life. I was perplexed at this, thinking that perhaps the little fellow might, after all, be in a trance. While I was considering the matter, I perceived a bystander looking very grave, and evidently having something on her mind. On asking her what she wished to say, I received for answer that, though she did not put any faith in it herself, yet people did say that such a thing was the sign of another death in the family within the twelve-month. If every remnant of Christmas decoration is not cleared out of church before Candlemas-day (the Purification, February 2), there will be a death that year in the family occupying the pew where a leaf or berry is left. An old lady (now dead) whom I knew, was so persuaded of the truth of this superstition, that she would not be contented to leave the clearing of her pew to the constituted authorities, but used to send her servant on Candlemas-eve to see that her own seat at any rate was thoroughly freed from danger. Fires and candles also afford presages of death. Coffins flying out of the former, and winding-sheets guttering down from the latter. A winding-sheet is produced from a candle, if, after it has guttered, the strip, which has rum down, instead of being absorbed into the general tallow, remains unmelted: if, under these circumstances, it curls over away from the flame, it is a presage of death to the person in whose direction it points. Coffins out of the fire are hollow oblong cinders spirted from it, and are a sign of a coming death in the family. I have seen cinders, which have flown out of the fire, picked up and examined to see what they presaged; for coffins are not the only things that are thus produced. If the cinder, instead of being oblong, is oval, it is a cradle, and predicts the advent of a baby; while, if it is round, it is a purse, and means prosperity. The howling of a dog at night under the window of a sick-room, is looked upon as a warning of death's being near. Perhaps there may be some truth in this notion. Everybody knows the peculiar odour which frequently precedes death, and it is possible that the acute nose of the dog may perceive this, and that it may render him uneasy: but the same can hardly be alleged in favour of the notion, that the screech of an owl flying past signifies the same, for, if the owl did scent death, and was in hopes of prey, it is not likely that it would screech, and so give notice of its presence. Suffolk. C. W. J. THE HOT WEDNESDAY OF 1808Farmers, and others engaged in outdoor pursuits, men of science, and others engaged in observations on meteorological phenomena, have much reason to doubt whether the reported temperatures of past years are worthy of reliance. In looking through the old journals and magazines, degrees of winter cold and summer heat are found recorded, which, to say the best of it, need to be received with much caution; seeing that the sources of fallacy were numerous. There was one particular Wednesday in 1808, for instance, which was marked by so high a temperature, as to obtain for itself the name of the 'Hot Wednesday;' there is no doubt the heat was great, even if its degree were overstated. At Hayes, in Middlesex, two thermometers, the one made by Ramsden, and the other by Cary, were observed at noon, and were found to record 90° F. in the shade. Men of middle age at that time, called to mind the 'Hot Tuesday' of 1790, which, however, was several degrees below the temperature of this particular Wednesday. Remembering that the average heat, winter and summer, of the West Indies, is about 82°, it is not surprising that men fainted, and horses and other animals died under the pressure of a temperature so unusual in England as 8° above this amount. In the shade, at an open window looking into St. James's Park, a temperature of 94° was observed. In a shop-window, on the shady side of the Strand, a thermometer marked 101°; but this was under the influence of conducted and radiant warmth from surrounding objects. At Gainsborough, in Lincolnshire, two thermometers, made by Nairne and Blunt respectively, hanging in the shade with a northern aspect, marked 94° at one o'clock on the day in question. In the corresponding month of 1825, observers were surprised to find a temperature of 85° marked in the quadrangle of the Royal Exchange at four o'clock in the 19th, 86½° at one o'clock on the same day, 87° at Paris, and 91° at Hull; but all these were below the indications noticed, or alleged to be noticed, in 1808. It is now known, however, better than it was in those days, that numerous precautions are necessary to the obtainment of reliable observations on temperature. The height from the ground, the nature and state of the ground, the direction in reference to the points of the compass, the vicinity of other objects, the nature of those objects as heat-reflectors, the covered or uncovered state of the space overhead-all affect the degree to which the mercury in the tube of a thermometer will be expanded by heat: even if the graduation of the tube be reliable, which is seldom the case, except in high-priced instruments. On this account all the old newspaper statements on such matters must be received with caution, though there is no reason to doubt that the Hot Wednesday of 1808 was really a very formidable day. |