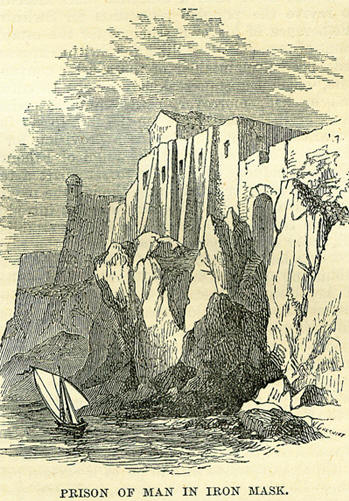

14th JulyBorn: Cardinal Mazarin, 1602, Pescina, in Abruzzo; Sir Robert Strange, engraver, 1721, Orkney; John Hunter, eminent surgeon, 1728, Long Calderwood; Aaron Arrowsmith, publisher of maps, 1750, Winston, Durham; John S. Bowerbank, naturalist, 1797, London. Died: Philip Augustus of France, 1223, Mantes; Dr. William Bates, eminent physician, 1699, Hackney; Dr. Richard Bentley, editor, controversialist, 1742, Cambridge; Colin Maclaurin, mathematician, 1746, Edinburgh; General Laudohn, 1790; Gartner, German botanist, 1791; Jean Paul Marat, French revolutionist, assassinated, 1793; Baroness De Staël Holstein (nee Anne Necker), 1817, Paris. Feast Day: St. Idus, bishop of Ath-Fadha, in Leinster; St. Bona-venture, cardinal and bishop, 1274; St. Camillus de Lellis, confessor, 1614. PHILIP AUGUSTUS OF FRANCEThe name of Philip Augustus is better known in English history than those of most of the earlier French monarchs, on account of his relations with the chivalrous Richard Coeur-de-Lion and the unpopular King John. Philip's reign was a benefit to France, as he laboured successfully to overcome feudalism, and strengthen and consolidate the power of the crown. He came to the throne when he was only fifteen years of age, and already displayed a vigour of mind which was beyond his years. One of the earlier acts of his reign, was the persecution of the Jews, who, on the charge of having crucified a Christian child at Easter, were stripped of their possessions, and banished from France; but this was less an act of religious bigotry, than probably an expedient for enriching his treasury. While King Henry II of England lived, Philip encouraged the two young English princes, Geoffrey and Richard, in rebelling against their father, because he aimed at getting possession of the English territories in France; and after Henry's death, he professed the closest friendship for Richard, who succeeded him on the throne, and joined with him in the third Crusade. This, however, was the result neither of religious zeal nor of sincere friendship; for, as is well known to all readers, he quarrelled with King Richard on the way to the East, and became his bitter enemy, and soon abandoned the crusade and returned home. He was restrained by his oath, and still more by the threats of the pope, and by the fear of incurring the odium of all Western Europe, from attacking King Richard's possessions during his absence; but he intrigued against him, incited his subjects to rebellion, assisted his brother John in his attempt to usurp his throne, and when Richard had been seized and imprisoned by the emperor of Austria, he offered money to that monarch to induce him to keep him in confinement. By the death of Richard Coeur-de-Lion, Philip was released from a powerful and dangerous enemy, and he soon commenced hostilities against his successor, King John, with whom he had previously been in secret and not very honourable alliance. The result of this war was, that in 1204, King John was stripped of his Norman duchy, which was reunited to the crown of France, and the English king gained from his Norman subjects the derisive title of Jehan sans Terre, which was Anglicised by the later English annalists into John Lack-land. Philip's plans of aggrandizement in the north and west were no doubt assisted by the absence of the great barons of the south, who might have embarrassed him in another crusade, in which they conquered not Jerusalem, but Constantinople and Greece. Philip invaded and occupied Brittany, and other provinces which were under English influence and rule, while King John made a feeble and very short attempt at resistance. These events were followed by the terrible crusade against the heretical Albigeois, which Philip encouraged, no doubt from motives of crafty policy, and not from either religious bigotry or attachment to the pope. Nevertheless, the pope, as is well known, was so well satisfied with Philip's conduct in this cause, that he struck the English nation with the interdict, and nominally deposed King John from his throne, transferred the crown of England by his authority to the head of Philip Augustus, and authorised him to go and take possession of it by force, promising the privilege of crusaders in this world and the next to all who should assist him in this undertaking. This expedition was retarded by a war with the Count of Flanders, which led to a coalition between the count, the emperor of Germany, and the king of England, against the French king; but the war was ended advantageously for Philip, by his victory in the battle of Bouvines. Philip now found sufficient occupation for a while in regulating the internal affairs of his own country, and in resisting the rather undisguised aspirations of his subjects for popular liberty; while his enemy, King John, was engaged in a fiercer struggle with his own barons; but there had been a change which Philip did not expect, for the pope, who hated everything like popular liberty, no sooner saw that it was for this object, in some degree, that the English barons were fighting, than he altered his policy, took King John under his protection, and forbade the king of France to interfere further. Philip had no love for the pope, and was seldom inclined to submit to any control upon his own will; and when the English barons, in their discouragement, sought his assistance, and offered the crown of England to his son, the prince Louis (afterwards King Louis VIII of France), he accepted and sent Louis with an army to England, in defiance of the pope's direct prohibition. The death of King John, and the change of feelings in England which followed that event, finally put an end to his ambitious hopes in that direction. The remainder of Philip's reign presented no events of any great importance except the renewal of the war in the south, in which the first Simon do Montford was slain in the year 1218. Philip Augustus died at Mantes, on the 14th of July 1223, at the age of fifty-eight, leaving the crown of France far more powerful than he had found it. Philip's accession to the throne of France, when he was only a child, was accompanied by a rather romantic incident. His father, who, as was then usual, was preparing to secure the throne to his son by crowning him during his lifetime, and who was residing, in a declining state of health, at Compiegne, gave the young prince permission to go to the chase with his huntsmen. They had hardly entered the forest, before they found a boar, and the hunters uncoupled the hounds, and pursued it till they were dispersed in different directions among the wildest parts of the woods. Philip, on a swift horse, followed eagerly the boar, until his steed slackened its pace through fatigue, and then the young prince found that he was entirely separated from his companions, and ignorant of the direction in which he might hope to find them. After he had ridden back-wards and forwards for some time, night set in, and the prince, left thus alone in the midst of a vast and dreary forest, became seriously alarmed. In this condition he wandered about for several hours, until at last, attracted by the appearance of a light, he perceived at a distance a peasant who was blowing the fire of a charcoal kiln. Philip rode up to him, and told him who he was, and the accident which had happened to him, though his fear was not much abated by the collier's personal appearance, for he was a large, strong, and rough-looking man, with a forbidding face, rendered more ferocious by being blackened with the dust of his charcoal, and he was armed with a formidable axe. His behaviour, however, did not accord with his appearance, for he immediately left his charcoal, and conducted the prince safely back to Compiegne; but fear and fatigue threw the child into so violent an illness, that it was found necessary to postpone the coronation more than two months. MARAT The sanguinary fanaticism of the French Revolution has no representative of such odious and repulsive figure as Marat, the original self-styled 'Friend of the People.' By birth a Swiss, of Calvinistic parents, he had led a strange skulking life for five-and-forty years-latterly, a sort of quack mediciner-when the great national crisis brought him to the surface as a journalist and member of the Convention. Less than five feet high, with a frightful countenance, and maniacal eye, he was shrunk from by most people as men shrink from a toad; but he had frantic earnestness, and hesitated at no violence against the enemies of liberty, and so he came to possess the entire confidence and affection of the mob of Paris. His constant cry was for blood; he literally desired to see every well-dressed person put to death. Every day his paper, L'Ami du Peuple, was filled with clamorous demands for slaughter, and the wish of his heart was but too well fulfilled. By the time that the summer of 1793 arrived, he was wading in the blood of his enemies. It was then that the young enthusiastic girl, Charlotte Corday, left her native province, for Paris, to avenge the fate of her friend, Barbaroux. She sought Marat at his house-was admitted to see him in his hot bath-and stuck a knife into his heart. His death was treated as a prodigious public calamity, and his body was deposited, with extravagant honours, in the Pantheon; but public feeling took a turn for the better ere long, and the carcass of the wretch was then ignominiously extruded. To contemporaries, the revolutionary figure of Marat had risen like a frightful nightmare: nobody seemed to know whence he had come, or how he had spent his previous life. There was, however, one notice of his past history published in a Glasgow newspaper, four months before his death, rather startling in its tenor; which, nevertheless, would now appear to have been true. It was as follows: From an investigation lately taken at Edinburgh, it is said that Marat, the celebrated orator of the French National Convention, the humane, the mild, the gentle Marat, is the same person who, a few years ago, taught tambouring in this city under the name of John White. His conduct while he was here was equally unprincipled, if not as atrocious, as it has been since his elevation to the legislator-ship. After contracting debts to a very consider-able amount, he absconded, but was apprehended at Newcastle, and brought back to this city, where he was imprisoned. He soon afterwards executed a summons of cessio bonorum against his creditors, in the prosecution of which, it was found that he had once taught in the academy at Warrington, in which Dr. Priestley was tutor; that he left Warrington for Oxford, where, after some time, he found means to rob a museum of a number of gold coins, and medallions; that he was traced to Ireland, apprehended at an assembly there in the character of a German count; brought back to this country, tried, convicted, and sentenced to some years' hard labour on the Thames. He was refused a cessio, and his creditors, tired of detaining him in jail, after a confinement of several months, set him at liberty. He then took up his residence in this neighbourhood, where he continued about nine months, and took his final leave of this country about the beginning of the year 1787. He was very ill-looked, of a diminutive size, a man of uncommon vivacity, a very turbulent disposition, and possessed of a very uncommon share of legal knowledge. It is said that, while here, he used to call his children Marat, which he said was his family name. These revelations regarding Marat were certainly calculated to excite attention. Probably, however, resting only on an anonymous newspaper paragraph, they were little regarded at the time of their publication. It is only of late years that we have got any tolerably certain light regarding Marat's life in England. It now appears that he was in this country in 1774, when thirty years of age, being just the time when the differences between the American colonists and the mother-country were coming to a crisis. In that year he published, in English, a huge pamphlet (royal 8vo, price 12s.), under the title of 'The Chains of Slavery: a work wherein the clandestine and villainous attempts of princes to ruin liberty are pointed out, and the dreadful scenes of despotism disclosed; to which is prefixed An Address to the Electors of Great Britain, in order to draw their timely attention to the choice of proper representatives in the next Parliament.-Becket, London.' Most likely, this work would meet with but little encouragement in England, for the current of public feeling ran in the opposite direction. In 1776, we find him dating from Church Street, Soho, a second and much less bulky pamphlet on a wholly different subject-An Inquiry into the Nature, Cause, and Cure of a Singular Disease of the Eyes, hitherto unknown, and yet common, produced by the use of certain Mercurial Preparations. By J. P. Marat, M.D. He here vented some quackish ideas he had regarding eye-disease, and out of which he is said at one time to have made a kind of living in Paris. In the prefatory address to the Royal Society, he lets out that he had been in Edinburgh in the previous August (1775). It is stated, but we do not know on what authority, that, in the Scottish capital, he tried to support himself by giving lessons in French. He probably was not there long, but quickly migrated to the academy at Warrington. Nor was he there long either. The next incident in his life was the Oxford felony, adverted to in the Glasgow Star. At least there can be little doubt that the following extract from a letter of Mr. Edward Creswell, of Oxford, dated February 12, 1776, refers to Marat under an assumed name: ... I shall now tell you a piece of news respecting a robbery which was committed here lately. . . . About a week ago, a native of France, who calls himself M. he Maitre, and was formerly a teacher in Warrington Academy, being invited here by a gentleman of this college to teach the French language, came over, and met with great encouragement in the university, but, happening to get acquainted with Mr. Milnes, a gentleman of Corpus Christi College, who is the keeper of the museum and several other natural curiosities, he prevailed on him, by repeated importunities, to let him have a view of them. Accordingly, they both went together, and after M. le Maitre had viewed them a great while, Mr. Milnes, from the suspicions he entertained of his behaviour, under pretence of getting rid of him, told him that several gentlemen were waiting at the door for admittance, and that he must now go out immediately; but the Frenchman excused himself by saying he would retire into the other apartments, and whilst the strangers that were admitted were surveying the curiosities with more than ordinary attention, this artful villain retired from them, and concealed himself under a dark staircase that led into the street, where he stayed till the company had gone out, after which he stole away medals and other coins to the amount of two hundred pounds and upwards, and got clear off with his booty. It was somewhat observable that he was often seen lurking near the museum some time before this affair happened, and very frequently desired to be admitted as soon as he had got a view of the medals. I am sorry I have not time to tell you a few more particulars concerning this transaction, but shall defer it till I know further about it. In a subsequent letter, Mr. Creswell informed his correspondent that the Frenchman who robbed the museum was tried, and being found guilty, was 'sentenced to work on the river Thames for five years.' These extracts appear, with due authentication, in the Notes and Queries (September 16, 1860), and they are supported in their tenor by the publications of the day. The robbery of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford by a person styled at first 'a Swiss hair-dresser,' and afterwards 'Le Mair, now a prisoner in Dublin,' is noticed in the Gentleman's Magazine for February and March 1776. Subsequently, it is stated in the same work under September 1, that 'Petre le Maitre, the French hair-dresser, who robbed the museum at Oxford of medals, &c., to a considerable amount, was brought by habeas corpus from Dublin, and lodged in Oxford Castle.' Unfortunately, this record fails to take notice of the trial. What a strange career for a Swiss adventurer from first to last! A pamphleteer for the illumination of British electors, a pamphleteer for a quack cure for the eyes, a teacher of languages at Edinburgh, an usher at the Warrington Academy under the sincere and profound Priestley, a felon at Oxford, a for cat for five years on the Thames, afterwards a teacher of tambouring at Glasgow, running into debt, and going through a struggle for white-washing by the peculiar Scotch process of cessio bonorum, which involves the preliminary necessity of imprisonment; finally, for a brief space, the most powerful man in France, and, in that pride of place, struck down by a romantic assassination-seldom has there been such a life. One can imagine, however, what bitterness would be implanted in such a nature by the felon's brand and the long penal servitude, and even by the humiliation of the cessio bonorum, and how, with these experiences rankling beyond sympathy in the wretch's lonely bosom, he might at length come to revel in the destruction of all who had deserved better than himself. 'DE HERETICO COMBURENDO'Amongst the last victims of the religious persecution under Mary, were six persons who formed part of a congregation caught praying and reading the Bible, in a by-place at Islington, in May 1558. Seven of the party had been burned at Smithfield on the 27th of June; the six who remained were kept in a miserable confinement at the palace of Bonner, bishop of London, at Fulham, whence they were taken on the 14th of July, and despatched in a similar manner at Brentford. While these six unfortunates lay in their vile captivity at Fulham, Bonner felt annoyed at their presence, and wished to get them out of the way; but he was sensible, at the same time, of there being a need for getting these sacrifices to the true church effected in as quiet a way as possible. He therefore penned an epistle to (apparently) Cardinal Pole, which has lately come to light, and certainly gives a curious idea of the coolness with which a fanatic will treat of the destruction of a few of his fellow-creatures when satisfied that it is all right. 'Further,' he says, 'may it please your Grace concerning these obstinate heretics that do remain in my house, pestering the same, and doing snuck hurt many ways, some order may be taken with them, and in mine opinion, as I shewed your Grace and my Lord Chancellor, it should do well to have them brent in Hammersmith, a mile from my house here, for then I can give sentence against them here in the parish church very quietly, and without tumult, and having the sheriff present, as I can have him, he, without business or stir, [call] put them to execution in the said place, when otherwise the thing [will need a] day in [St] Paul's, and with more comberance than now it needeth. Scribbled in haste, &c' Bonner was a man of jolly appearance, and usually of mild and placid speech, though liable to fits of anger. In the ordinary course of life, he would probably have rather done one a kindness than an injury. See, however, what fanaticism made him. He scribbles in haste a letter dealing with the lives of six persons guilty of no real crime, and has no choice to make in the case but that their condemnation and execution may be conducted in a manner as little calculated to excite the populace as possible. BEAR-BAITINGIn the account which Robert Laneham gives of the festivities at Kenilworth Castle, in 1575, on the reception of Queen Elizabeth by her favourite minister, the Earl of Leicester, there is a lively though conceited description of the bear and dog combats which formed part of the entertainments prepared for her majesty, and which took place on the sixth day of her stay (Friday, 14th July). There were assembled on this occasion thirteen bears, all tied up in the inner court, and a number of ban-dogs (a small kind of mastiff). The bears were brought forth into the court, the dogs set to them, to argue the points even face to face. They had learned counsel also o' both parts; what, may they be counted partial that are retain[ed] but a to [to one] side? I ween no. Very fierce both tone and tother, and eager in argument; if the dog, in pleading, would pluck the bear by the throat, the bear, with traverse, would claw him again by the scalp; confess an a [he] list, but avoid a [he] could not, that was bound to the bar; and his counsel told him that it could be to him no policy in pleading. Therefore thus with fending and fearing, with plucking and tugging, scratching and biting, by plain tooth and nail to [the one] side and tother, such expense of blood and leather was there between them, as a month's licking, I ween, will not recover; and yet [they] remain as far out as ever they were. It was a sport very pleasant of these beasts, to see the bear with his pink eyes leering after his enemy's approach, the nimbleness and weight of the dog to take his advantage, and the force and experience of the bear again to avoid the assaults; if he were bitten in one place, how he would pinch in another to get free; if he were taken once, then what shift, with biting, with clawing, with roaring, tossing, and tumbling, he would work to wind himself from them, and when he was loose, to shake his ears twice or thrice, with the blood and the slaver about his phisnomy, was a matter of goodly relief.  In the twelfth century, the baiting of bulls and bears was the favourite holiday pastime of Londoners; and although it was included in a proclamation of Edward III, among 'dishonest, trivial, and useless games,' the sport increased in popularity with all classes. Erasmus, who visited England in the reign of Henry VIII, speaks of 'many herds' of bears regularly trained for the arena; the rich nobles had their bearwards, and the royal establishment its 'master of the king's bears.' For the better accommodation of the lovers of the rude amusement, the Paris Garden Theatre was erected at Bankside, the public being admitted at the charge of a penny at the gate, a penny at the entry of the scaffold, and a penny for quiet standing. When Queen Mary visited her sister during her confinement at Hatfield House, the royal ladies were entertained with a grand baiting of bulls and bears, with which they declared themselves 'right well contented.' Elizabeth took especial delight in seeing the courage of her English mastiffs pitted against the cunning of Ursa and the strength of Taurus. On the 25th of May 1559, the French ambassadors 'were brought to court with music to dinner, and after a splendid dinner, were entertained with the baiting of bears and bulls with English dogs. The queen's grace herself, and the ambassadors, stood in the gallery looking on the pastime till six at night.' The diplomatists were so gratified, that her majesty never failed to provide a similar show for any foreign visitors she wished to honour. Much as the royal patron of Shakspeare and Burbage was inclined to favour the players, she waxed indignant when the attractions of the bear-garden paled before those of the theatre; and in 1591 an order issued from the privy-council for-bidding plays to be acted on Thursdays, because bear-baiting and such pastimes had usually been practised on that day. This order was followed by an injunction from the lord mayor to the same effect, in which his lordship complained, 'that in divers places, the players do use to recite their plays to the great hurt and destruction of the game of bear-baiting, and such-like pastimes, which are maintained for her majesty's pleasure.' An accident at the Paris Garden in 1583, afforded the Puritans an opportunity for declaring the popular sport to be under the ban of Heaven-a mode of argument anticipated years before by Sir Thomas More in his Dialogue. At Beverley late, much of the people being at a bear-baiting, the church fell suddenly down at evening time, and overwhelmed some that were in it. A good fellow that after heard the tale told, 'So,' quoth he, 'now you may see what it is to be at evening prayers when you should be at the bear-baiting!' 'Some of the ursine heroes of those palmy-days of bear-baiting have been enshrined in verse. Sir John Davy reproaches the law-students with 'Leaving old Plowden, Dyer, and Brooke alone, To see old Harry Hunks and Sackerson. The last named has been immortalised by Shakspeare in his Merry Wives of Windsor-Slender boasts to sweet Anne Page, 'I have seen Sackerson loose twenty times; and have taken him by the chain: but, I warrant you, the women have so cried and shrieked at it, that it passed.' James I prohibited baiting on Sundays, although he did not otherwise discourage the sport. In Charles I's reign, the Garden at Bankside was still a favourite resort, but the Commonwealth ordered the bear to be killed, and forbade the amusement. However, with the Restoration it revived, and Burton speaks of bull and bear baiting as a pastime: in which our countrymen and citizens greatly delight and frequently use. On the 14th of August 1666, Mr. Pepys went to the Paris Garden, and saw: some good sports of the bulls tossing the dogs, one into the very boxes; and that it had not lost the countenance of royalty, is proved by the existence of a warrant of Lord Arlington's for the payment of ten pounds to James Davies, Esq., master of his majesty's bears, bulls, and dogs, 'for making ready the rooms at the bear-garden, and baiting the bears before the Spanish ambassadors, the 7th of January last' (1675). After a coming bear-baiting had been duly advertised, the bearward used to parade the streets with his champions. 'I'll set up my bills,' says the sham bearward in The Humorous Lovers, 'that the gamesters of London, Horsleydown, Southwark, and Newmarket may come in, and bait him before the ladies. But first, boy, go fetch me a bagpipe; we will walk the streets in triumph, and give the people notice of our sport.' Sometimes the bull or bear was decorated with flowers, or coloured ribbons fastened with pitch on their fore-heads, the dog who pulled off the favour being especially cheered by the spectators. The French advocate, Misson, who lived in England during William III's reign, gives a vivid description of 'the manner of these bull-baitings, which are so much talked of. They tie a rope to the root of the horns of the bull, and fasten the other end of the cord to an iron ring fixed to a stake driven into the ground; so that this cord, being about fifteen feet long, the bull is confined to a space of about thirty feet diameter. Several butchers, or other gentlemen, that are desirous to exercise their dogs, stand round about, each holding his own by the ears; and when the sport begins, they let loose one of the dogs. The dog runs at the bull; the bull, immovable, looks down upon the dog with an eye of scorn, and only turns a horn to him, to hinder him from coming near. The dog is not daunted at this, he runs round him, and tries to get beneath his belly. The bull then puts himself into a posture of defence; he beats the ground with his feet, which he joins together as closely as possible, and his chief aim is not to gore the dog with the point of his horn (which, when too sharp, is put into a kind of wooden sheath), but to slide one of them under the dog's belly, who creeps close to the ground, to hinder it, and to throw him so high in the air that he may break his neck in the fall. To avoid this danger, the dog's friends are ready beneath him, some with their backs, to give him a soft reception; and others with long poles, which they offer him slantways, to the intent that, sliding down them, it may break the force of his fall. Notwithstanding all this care, a toss generally makes him sing to a very scurvy tune, and draw his phiz into a pitiful grimace. But unless he is totally stunned with the fall, he is sure to crawl again towards the bull, come on't what will. Sometimes a second frisk into the air disables him for ever; but sometimes, too, he fastens upon his enemy, and when once he has seized him with his eye-teeth, he sticks to him like a leech, and would sooner die than leave his hold. Then the bull bellows and bounds and kicks, all to shake off the dog. In the end, either the dog tears out the piece he has laid hold on, and falls, or else remains fixed to him with an obstinacy that would never end, did they not pull him off. To call him away, would be in vain; to give him a hundred blows, would be as much so; you might cut him to pieces, joint by joint, before he would let him loose. What is to be done then? While some hold the bull, others thrust staves into the dog's mouth, and open it by main force.' In the time of Addison, the scene of these animal combats was at Hockley in the Hole, near Clerkenwell. The Spectator of August 11, 1711, desires those who frequent the theatres merely for a laugh, would 'seek their diversion at the bear-garden, where reason and good-manners have no right to disturb them.' Gay, in his Trivia, says: Experienced men, inured to city ways, Need not the calendar to count their days. When through the town, with slow and solemn air, Led by the nostril walks the muzzled bear; Behind him moves, majestically dull, The pride of Hockley Hole, the surly bull. Learn hence the periods of the week to name- Mondays and Thursdays are the days of game. The over-fashionable amusement had fallen from its high estate, and was no longer upheld by the patronage of the higher classes of society. In 1802, a bill was introduced into the Commons for the suppression of the practice altogether. Mr. Windham opposed the measure, as the first result of a conspiracy of the Jacobins and Methodists to render the people grave and serious, preparatory to obtaining their assistance in the furtherance of other anti-national schemes, and argued as if the British Constitution must stand or fall with the bear-garden; and Colonel Grosvenor asked, if 'the higher orders had their Billington, why not the lower orders their Bull?' This extraordinary reasoning prevailed against the sarcasm of Courtenay, the earnestness of Wilberforce, and the eloquence of Sheridan, and the House refused, by a majority of thirteen, to abolish what the last-named orator called 'the most mischievous of all amusements.' This decision of the legislature doubtless received the silent approval of Dr. Parr, for that learned talker was a great admirer of the sport. A bull-baiting being advertised in Cambridge, during one of his last visits there, the doctor hired a garret near the scene of action, and taking off his academic attire, and changing his notorious wig for a night-cap, enjoyed the exhibition incog. from the windows. This predilection was unconquerable. 'You see,' said he, on one occasion, exposing his muscular hirsute arm to the company, 'that I am a kind of taurine man, and must therefore be naturally addicted to the sport.' It was not till the year 1835 that baiting was finally put down by an act of parliament, forbidding the keeping of any house, pit, or other place for baiting or fighting any bull, bear, dog, or other animal; and after an existence of at least seven centuries, this ceased to rank among the amusements of the English people. AN EXPLOSION IN THE COURT OF KING'S BENCHOn the 14th of July 1737, when the courts were sitting in Westminster Hall, between one and two o'clock in the afternoon, a large brown-paper parcel, containing fireworks, which had been placed, unobserved, near the side-bar of the Court of King's Bench, exploded with a loud noise, creating great confusion and terror among the persons attending the several courts. As the crackers rattled and burst, they threw out balls of printed bills, purporting that, on the last day of term, five libels would be publicly burned in Westminster Hall. The libels specified in the bills were five very salutary but most unpopular acts of parliament, lately passed by the legislature. One of these printed bills, being taken to the Court of King's Bench, the grand jury presented it as a wicked, false, and scandalous libel; and a proclamation was issued for discovering the persons concerned in this 'wicked and audacious outrage.' A reward of £200 was offered for the detection of the author, printer, or publisher of the bills; but the contrivers of this curious mode of testifying popular aversion to the measures of parliament were never discovered. DESTRUCTION OF THE BASTILE-THE MAN IN THE IRON MASKThe 14th of July will ever be a memorable day in French history, as having witnessed, in 1789, the demolition, by the Paris populace, of the grin old fortress identified with the despotism and cruelty of the falling monarchy. It was a typical incident, representing, as it were, the end of a wicked system, but unfortunately not inaugurating the beginning of one milder and better. Much heroism was shewn by the multitude in their attack upon the Bastile, for the defenders did not readily submit, and had a great advantage behind their lofty walls. But their triumph was sadly stained by the massacre of the governor, Delaunay, and many of his corps.  'It was now,' says Lamartine, 'that the mysteries of this state-prison were unveiled-its bolts broken -its iron doors burst open-its dungeons and subterranean cells penetrated-from the gates of the towers to their very deepest foundations and their summits. The iron rings and the chains, rusting in their strong masonry, were pointed out, from which the victims were never released, except to be tortured, to be executed, or to die. On those walls they read the names of prisoners, the dates of their confinement, their griefs and their prayers -miserable men, who had left behind only those poor memorials in their dungeons to attest their prolonged existence and their innocence! It was surprising to find almost all these dungeons empty. The people ran from one to the other: they penetrated into the most secret recesses and caverns, to carry thither the word of release, and to bring a ray of the free light of heaven to eyes long lost to it; they tore the locks from the heavy doors, and those heavy doors from the hinges; they carried off the heavy keys; all these things were displayed in triumph in the open court. They then broke into the archives, and read the entries of committals. These papers, then ignominiously scattered, were afterwards collected. They were the annals of arbitrary times, the records of the fears or vengeance of ministers, or of the meaner intrigues of their favourites, here faithfully kept to justify a late exposure and reproach. The people expected to see a spectre come forth from these ruins, to testify against these iniquities of kings. The Bastile, however, long cleared of all guilt by the gentle spirit of Louis XVI, and by the humane disposition of his ministers, disappointed these gloomy expectations. The dungeons, the cells, the iron collars, the chains, were only worn-out symbols of antique secret incarcerations, torture, and burials alive. They now represented only recollections of old horrors. These vaults restored to light but seven prisoners-three of whom, gray-headed men, were shut up legitimately, and whom family motives had withdrawn from the judgments of the ordinary courts of law. Tavernier and Withe, two of them, had become insane. They saw the light of the sun with surprise; and their incurable insanity caused them to be sent to the madhouse of Charenton, a few days after they had enjoyed fresh air and freedom. The third was the Count de Solages, thirty-two years before sent to this prison at his father's request. When restored free to Toulouse, his home, he was recognised by none, and died in poverty. Whether he had been guilty of some crime, or was the victim of oppression, was an inexplicable enigma. The other four prisoners had been confined only four years, and on purely civil grounds. They had forged bills of exchange, and were arrested in Holland on the requisition of the bankers they had defrauded. A royal commission had reported on their cases; but nothing was now listened to against them. What-ever had been branded by absolute authority, must be innocent in the eyes of the prejudiced people. These seven prisoners of the Bastile became victims -released, caressed, even crowned with laurels, carried in triumph by their liberators like living spoil snatched from the hands of tyranny, they were paraded about the streets, and their sufferings avenged by the people's shouts and tears. The intoxication of the victors broke out against the very stones of the place, and the embrasures, torn from the towers, were soon hurled with indignation into the ditches.' It was asserted at the time, and long afterwards believed-though there was no foundation for the averment-that the wasted body of the famous state-prisoner, called the Man in the Iron Mask, had been found chained in a lower dungeon, with the awful mask still upon the skull! Speculations had long been rife among French historians, all tending to elucidate the mystery connected with that celebrated prisoner. By some, it was hinted that he was the twin-brother of Louis XIV, thus frightfully sacrificed to make his senior safe on his throne; others affirmed him to be the English Duke of Monmouth; others, a son of Oliver Cromwell; many, with more reason, inclining to think him a state-prisoner of France, such as the Duke de Beaufort, or the Count de Vermandois. It was reserved for M. Delort, at a comparatively recent period, to penetrate the mystery, and enable the late Lord Dover to compile and publish, in 1825, his True History of this unfortunate man; the facts being gathered from the state archives of France, and documentary evidence of conclusive authority. It appears that this mysterious prisoner was Count Anthony Matthioli, secretary of state to Charles III, Duke of Mantua, and afterwards to his son Ferdinand, whose debauched habits, and consequent need, laid him open to a bribe from Louis XIV for permission to place an army of occupation in his territory, with a view to establish French influence in Italy. Matthioli had expressed his readiness to aid the plot; had visited Paris, and had a secret interview with the king, who presented him with a valuable ring and a considerable sum of money; but when the time came for vigorous action, Matthioli, who appears to have been intriguing with the Spanish court for a better bribe, placed all obstacles and delays in the way of France. The French envoy, the Baron Asfeld, was arrested by the Spanish governor of the Milanese; and the French court found that their diplomacy was betrayed. Louis determined to satisfy his wounded pride and frustrated ambition, by taking the most signal vengeance on Matthioli. The unfortunate secretary was entrapped at a secret interview on the frontier, and carried to the French garrison at Pignerol, afterwards to the fortress of Exiles; when his jailer, St. Mars, was appointed governor of the island of St. Marguerite (opposite Cannes), he was immured in the fortress there, and so remained for eleven years. In the autumn of 1698, St. Mars was made governor of the Bastile, and thither Matthioli was conveyed, dying within its gloomy walls on the 19th of November 1703. He had then been twenty-four years in this rigorous confinement, and had reached the age of sixty-three. Throughout this long captivity, Louis never shewed him any clemency. The extraordinary precautions against his discovery, and the one which appears to have been afterwards resorted to, of obliging him to wear a mask during his journeys, or when he saw any one, are not wonderful, when we reflect upon the violent breach of the law of nations which had been committed by his imprisonment. Matthioli, at the time of his arrest, was actually the plenipotentiary of the Duke of Mantua for concluding a treaty with the king of France; and for that very sovereign to kidnap him, and confine him in a dungeon, was one of the most flagrant acts of violence that could be committed; one which, if known, would have had the most injurious effects upon the negotiations of Louis with other sovereigns; nay, would probably have indisposed other sovereigns from treating at all with him. The confinement of Matthioli is decidedly one of the deadliest stains that blot the character of Louis XIV.  The prison of Matthioli, in the fortress of St. Marguerite, is now, for the first time, engraved from an original sketch. It is one of a series of five, built in a row on the scarp of the rocky cliff. The walls are fourteen feet thick; there are three rows of strong iron gratings placed equidistant within the arched window of Matthioli's room, a large apartment with vaulted roof, and no feature to bleak its monotony, except a small fireplace beside the window, and a few shelves above it. The Bay of Cannes, and the beautiful range of the Esterel mountains, may be seen from the window; a lovely view, that must have given but a maddening sense of confinement to the solitary prisoner. It is on record, that his mind was seriously deranged during the early part of his imprisonment; what he became ultimately, when all hope failed, and a long succession of years deadened his senses, none can know-the secret died with his jailers. There is a tradition, that he attempted to make his captivity known, by scratching his melancholy tale on a metal dish, and casting it from the window; that it was found by a fisherman of Cannes, who brought it to the governor, St. Mars, thereby jeopardising his own life or liberty, for he was at once imprisoned, and only liberated on incontestable proof being given of his inability to read. After this, all fishermen were prohibited from casting their nets within a mile of the island. Matthioli was debarred, on pain of death, from speaking to any but his jailer; he was conveyed from one dungeon to the other in a sedan-chair, closely covered with oil-cloth, into which he entered in his cell, where it was fastened so that no one should see him; his jailers nearly smothered him on his journey to St. Marguerite; and afterwards the black mask seems to have been adopted on all occasions of the kind. Lord Dover assures us, that it has been a popular mistake to affirm this famed mask was of iron; that, in reality, it was formed of velvet, strengthened by bands of whalebone, and secured by a padlock behind the head. The same extraordinary precautions for concealment followed his death that had awaited him in life. The walls of his dungeon were scraped to the stone, and the doors and windows burned, lest any scratch or inscription should betray the secret. His bedding, and all the furniture of the room, were also burned to cinders, then reduced to powder, and thrown into the drains; and all articles of metal melted into an indistinguishable mass. By this means it was hoped that oblivion might surely follow one of the grossest acts of political cruelty in the dark record of history. |