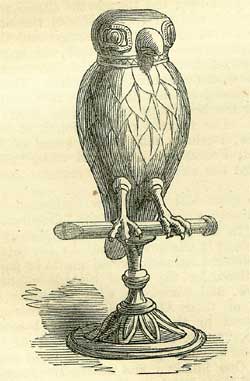

12th JulyBorn: Caius Julius Cæsar, 100 B.C. Died: Desiderius Erasmus, scholar, 1536, Basel; General St. Ruth, killed at Aghrim, Ireland, 1691; Titus Oates, 1704; Christian G. Heyne (illustrator of ancient writings), 1814, Gottingen; Dr. John Jamieson (Scottish Dictionary), 1838, Edinburgh; Mrs. Tonna ('Charlotte Elizabeth'), controversial writer, 1846; Horace Smith, novelist, comic poet, 1849; Robert Stevenson, engineer of Bell Rock light-house, &c., 1850. Feast Day: Saints Nabor and Felix, martyrs, about 304; St. John Gualbert, abbot, 1073. MRS. TONNAIt is quite possible to be an author and have one's books sold by thousands, and yet only attain a limited and sectional fame. Such was Mrs. Tonna's case. We remember overhearing a conversation between a young lady and a gentleman of almost encyclopaedic information, in which a book by Charlotte Elizabeth was mentioned. 'Charlotte Elizabeth!' Exclaimed he; 'who is Charlotte Elizabeth?' 'Don't you know Charlotte Elizabeth?' rejoined she; 'the writer of so many very nice books.' She was amazed at his ignorance, and probably estimated his acquirements at a much lower rate afterwards. 'Charlotte Elizabeth,' Miss Browne, Mrs. Pelhan, finally Mrs. Tonna, was the daughter of the rector of St. Giles, Norwich, and was born in that city on the 1st of October 1790. As soon as she could read she became an indiscriminate devourer of books, and when yet a child, once read herself blind for a season. Her favourite volume was Fox's Martyrs, and its spirit may be said to have become her spirit. Shortly after her father's death, she entered into an unhappy marriage with one Captain Pelhan, whose regiment she accompanied to Canada for three years. On her return, she settled on her husband's estate in Kilkenny, and mingling with the peasantry, she came to the conclusion that all their miseries sprang out of their religion. She thereon commenced to write tracts and tales illustrative of that conviction, which attracted the notice and favour of the Orange party, with whom she cordially identified herself. As her writings became remunerative, her husband laid claim to the proceeds, and to preserve them from sequestration, she assumed the name of 'Charlotte Elizabeth.' Her life henceforward is merely a tale of unceasing literary activity. Having become totally deaf, her days were spent between her desk and her garden. In the editorship of magazines, and in a host of publications, she advocated her religious and Protestant principles with a fervour which it would not be unjust to designate as, occasionally at least, fanatical. In 1837, Captain Pelhan died, and in 1841 she formed a happier union with Mr. Tonna, which terminated with her death at Ramsgate on the 12th of July 1846. Mrs. Tonna had a handsome countenance and in its radiance of intelligence and kindliness, a stranger would never imagine that he was in the presence of one whose religion and politics, theoretically, were those of the days of Elizabeth rather than of Victoria, and who was capable of saying in all earnestness, as she once did say to a young Protestant Irish lady of our acquaintance, on their being introduced to each other, 'Well, my dear, I hope you hate the Paapists!' THE FEMALE HEAD-DRESSES OF 1776 On the 12th of July 1776, Samuel Foote appeared at the Haymarket theatre in the character of Lady Pentweazle, wearing one of the enormous female head-dresses which were then fashionable-not meaning, probably, anything so serious as the reform of an absurdity, but only to raise a laugh, and bring an audience to his play-house. The dress is stated to have been stuck full of feathers of an extravagant size; it extended a yard wide; and the whole fabric of feathers, hair, and wool dropped off his head as he left the stage. King George and Queen Charlotte, who were present, laughed heartily at the exhibition; and her majesty, wearing an elegant and becoming head-dress, supplied a very fitting rebuke to the absurdity which the actor had thus satirised. There are numerous representations to be met with in books of fashions, and descriptions in books of various kinds, of the head-dress of that period. Sometimes it was remarkable simply for its enormous height; a lofty pad or cushion being placed on the top of the head, and the hair combed up over it, and slightly confined in some way at the top. Frequently, however, this tower was bedizened in a most extravagant manner, necessarily causing it to be broad as well as high, and rendering the whole fabric a mass of absurdity. It was a mountain of wool, hair, powder, lawn, muslin, net, lace, gauze, ribbon, flowers, feathers, and wire. Sometimes these varied materials were built up, tier after tier, like the successive stages of a pagoda. The London Magazine, in satirizing the fashions of 1777, said: Give Chloe a bushel of horse-hair and wool, Of paste and pomatum a pound, Ten yards of gay ribbon to deck her sweet skull, And gauze to encompass it round. Of all the bright colours the rainbow displays, Be those ribbons which hang on the head; Be her flounces adapted to make the folks gaze, And about the whole work be they spread; Let her flaps fly behind for a yard at the least, Let her curls meet just under her chin; Let these curls be supported, to keep up the jest, With an hundred instead of one pin. The New Bath Guide, which hits off the follies of that period with a good deal of sarcastic humour, attacked the ladies' head-dresses in a somewhat similar strain: A cap like a hat (Which was once a cravat) Part gracefully plaited and pin'd is, Part stuck upon gauze, Resembles macaws And all the fine birds of the Indies. But above all the rest, A bold Amazon's crest Waves nodding from shoulder to shoulder; At once to surprise And to ravish all eyes To frighten and charm the beholder. In short, head and feather, And wig altogether, With wonder and joy would delight ye; Like the picture I've seen Of th' adorable queen Of the beautiful bless'd Otaheite. Yet Miss at the Rooms Must beware of her plumes, For if Vulcan her feather embraces, Like poor Lady Laycock, She'd burn like a haycock, And roast all the Loves and the Graces. The last stanza refers to an incident in which a lady's monstrous head-dress caught fire, leading to calamitous results. BELL LEGENDSChurch-bells are beginning to awake a regard that has long slumbered. They have been deemed, too, recently, fit memorial of the mighty dead. Turrets, whose echoes have repeated but few foot-falls for a century, have been intrepidly ascended, and their clanging tenants diligently scanned for word or sign to tell their story. Country clergy-men, skewing the lions of their parishes to archaeological excursionists, have thought themselves happy in the choice of church-bells as the subject of the address expected of them. And it will be felt that some of the magic of the International Exhibition was due to the tumultuous reverberations of the deep, filling, quivering tones of the many bells. In monkish medieval times, church-bells enjoyed peculiar esteem. They were treated in great measure as voices, and were inscribed with Latin ejaculations and prayers, such as-Hail, Mary, full of grace, pray for us; St. Peter, pray for us; St. Paul, pray for us; St. Katharine, pray for us; Jesus of Nazareth, have mercy upon us; their tones, swung out into the air, would, ecstatically, appear to give utterence to the supplication with which they were inscribed. A bell in St. Michael's church, Alnwick, says, in quaint letters on a belt that is diapered with studs, 'Archangel Michael, come to the help of the people of God.' A bell at Compton Basset, which has two shields upon it, each bearing a chevron between three trefoils, says, 'Blessed be the name of the Lord.' Many bells are found to have identical inscriptions; there is, however, great variety, and further search would bring much more to light. In those old times, pious queens and gentle-women threw into the mass of metal that was to be cast into a bell their gold and silver ornaments; and a feeling of reverence for the interceding voices was common to gentle and simple. At Sudeley Castle, in the chapel, there is a bell, dated 1573, that tells us of the concern which the gentle dames of the olden time would take in this manufacture. It says, 'St. George, pray for us. The Lathe Doratie Chandos, Widdowe, made this.' They were sometimes cast in monasteries under the superintendence of ecclesiastics of rank. It is written that Sir William Corvehill, 'priest of the service of our Lady,' was a 'good bell-founder and maker of frames;' and on a bell at Sealton, in Yorkshire, we may read that it was made by John, archbishop of Graf. One of the ancient windows on the north side of the nave of York minster is filled with stained-glass, which is divided into subjects representing the various processes of bell-casting, bell-cleaning, and bell-tuning, and has for a border a series of bells, one below another; proving that the associations with which bells were regarded rendered them both ecclesiastical and pictorial in the eyes of the artists of old. The inscriptions on ancient bells were generally placed immediately below the haunch or shoulder, although they are sometimes found nearer the sound bow. The legends are, with few exceptions, preceded by crosses. Coats of arms are also of frequent occurrence, probably indicating the donors. The tones of ancient bells are incomparably richer and softer, more dulcet, mellow, and sufficing to the ear than those of the present iron age. King Henry VIII, however, looked upon church-bells only as so much metal that could be melted down and sold. Hence, in the general destruction and distribution of church-property in his reign, countless bells disappeared, to be sold as mere metal. Many curious coincidences attended this wholesale appropriation. Ships attempting to carry bells across the seas, foundered in several havens, as at Lynn, and at Yarmouth; and, fourteen of the Jersey bells being wrecked at the entrance of the harbour of St. Male, a saying arose to the effect, that when the wind blows the drowned bells are ringing. A certain bishop of Bangor, too, who sold the bells of his cathedral, was stricken with blindness when he went to see them shipped; and Sir Miles Partridge, who won the Jesus bells of St. Paul's, London, from King Henry, at dice, was, not long afterwards hanged on Tower Hill. Not-withstanding the regal and archiepiscopal disregard of bells, they did not, altogether, pass from popular esteem. Within the last half century, at Brenckburne, in Northumberland, old people pointed out a tree beneath which, they had been told when they were young, a treasure was buried. And when this treasure was sought and found, it turned out to be nothing more than fragments of the bell of the ruined priory church close by. Tradition recounts that a foraging-party of moss-trooping Scots once sought far and near for this secluded priory, counting upon the contents of the larders of the canons. But not a sign or a track revealed its position, for it stands in a cleft between the wooded banks of the Coquet, and is invisible from the high lands around. The enraged and hungry marauders-says the legend-had given up the search in despair, and were leaving the locality, when the monks, believing their danger past, bethought themselves to offer up thanksgivings for their escape. Unfortunately, the sound of the bell, rung to call them to this ceremony, reached the ears of the receding Scots in the forest above, and made known to them the situation of the priory. They retraced their steps, pillaged it, and then set it on fire. After the Reformation, the inscriptions on bells were addressed to man, not to Heaven; and were rendered in English. There is an exception to this rule, however, at Sherborne, where there is a fire-bell, 1652, addressed conjointly to Heaven and man: 'Lord, quench this furious flame; Arise, run, help, put out the same.' Many of the legends on seventeenth-century bells reflect the quaint times of George Herbert: When I ring, God's prayses sing; When I toule, pray heart and soule;' and, 'O man be meeke, and lyve in rest;' Geve thanks to God;' I, sweetly tolling, men do call To taste on meate that feeds the souk, are specimens of this period. More vulgar sentiments subsequently found place. 'I am the first, although but small, I will be heard above you all,' say many bells coarsely. A bell at Alvechurch says still more uncouthly, 'If you would know when we was run, it was March the twenty-second 1701. 'God save the queen,' occurs on an Elizabethan bell at Bury, Sussex, bearing date 1599; and on several others of the reign of Queen Anne, in Devonshire, and on one in Magdalen College, Oxford. 'God save our king,' is found first written on a bell at Stanford-upon-Soar, at the date of the accession of James I., 1603; it is of frequent occurrence on later bells; and the same sentiment is found produced in other forms, one of which is Feare God and honner the king, for obedience is a vertuous thing.' 'We have one bell that is dedicated to a particular service. It is the great bell of St. Paul's, London, which is only tolled on the death of sovereigns. The ordinary passing bell, now commonly called the dead-bell, used to be rung when the dying person was receiving the sacrament, so that those who wished to do so could pray for him at this moment; but it is now only rung after death, simply to inform the neighbourhood of the fact. In the same way the sanctus-bell used to be rung in the performance of mass, when the priest came to the words 'Sancte, Sancte, Sancte, Deus Sabaoth,' so that those persons unable to attend, might yet be able to bow down and worship at this particular moment. For this reason, the bell was always placed in a position where it might be heard as far as possible. In the gables of the chancel arches of ancient churches, are seen small square apertures, whose use few people can divine. It was through these that the ringers watched the services below, so as to be able to ring at the right time. The great bell of Bow owes its reputation to the nursery legend of 'Oranges and lemons, said the bells of St. Clement's;' not to any superior characteristics, for it is exceeded in size and weight by many others. English bells, generally, are smaller than those of foreign countries; perhaps for the reason that scientific ringing is not practised abroad; and all effect must be produced by the bells themselves, not by the mode in which they are handled. The more polite the nation, it is argued, the smaller their bells. The Italians have few bells, and those that they have are small. The Flemish and Germans, on the other hand, have great numbers of large bells. The Chinese once boasted of possessing the largest bells in the world; but Russia has since borne off the palm, or in others, carried away the bell, by hanging one in Moscow Cathedral, measuring 19 feet in height, and 63 feet 11 inches round the rim. By the side of these proportions our Big Bens and Big Toms are diminutive. The great bell of St. Paul's is but 9 feet in diameter, and weighs but 12,000 lbs. The largest bell in Exeter Cathedral weighs 17,470 lbs.; the famous Bow Bell but 5800 lbs. York, Gloucester, Canterbury, Lincoln, and Oxford, can also eclipse our familiar friend. France possesses a few ancient bells; some of them are ornamented with small bas-relievos of the Crucifixion, of the descent from the Cross, fleurs-de-lis, seals of abbeys and donors; and others have inscriptions of the same character as our own, each letter being raised on a small tablet more or less decorated. There was a bell in the abbey-church of Moissac (unfortunately recast in 1845), which was of a very rare and early date. An inscription on it, preceded by a cross, read, Salve Regina misericordiae Between the two last words was a bas-relief of the Virgin, and after them three seals; then followed a line in much smaller characters, Anno Domini millesimo cc' LXX. tercio Gofridus me fecit et socios meos. Paulus vocor. French bells were sometimes the gifts of kings and abbots; and were in every way held in as great esteem as those of our own country. In the accounts of the building of Troyes Cathedral, there is mention of two men coming to cast the bells, and of the canons visiting them at their work and stimulating them to perform it well, by harangues and by chanting the Te Deum. The canons finally assisted at the consecration of the bells. Bells have their literature as well as legends. Their histories are written in many russet-coloured volumes, in Latin, in French, and in Italian. These have been published in different parts of Europe, in Paris, in Leipsic, in Geneva, in Rome, in Frankfort, in Pisa, in Dresden, in Naples, in the fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. They take the forms of dissertations, treatises, descriptions, and notes. Early English writers confined themselves more especially to elucidating the art of ringing in essays bewilderingly technical. The names of the different permutations read like the reverie of a lunatic-single bob, plain bob, grandsire bob, single bob minor, grandsire treble, bob major, caters, bob royal, and bob maximus; and the names of the parts of a bell are quite as puzzling to the uninitiated. There are the canons, called also ansa, the haunch, otherwise cerebrum vel caput, the waist, latus, the sound-bow, the mouth, or labium, the brim, and the clapper. There is a manuscript in the British Museum of the 'Orders of the Company of ringers in Cheapside, 1603,' the year of Queen Elizabeth's death. And a work published in 1684, the last year of the reign of Charles I, called The School of Recreation, or Gentleman's Tutor, gives ringing as one of the exercises in vogue. There are, besides these, True Guides for Ringers, and Plain Hints for Ringers, a poem in praise of ringing, written in 1761, by the author of Shrubs of Parnassus, and other curious tracts of no value beyond their quaintness. Schiller has sung the song of the bell in vigorous verse; and in our own day the subject has received much literary care at the hands of more than one country clergyman. There is another bell legend to be told. On the eve of the feast of Corpus Christi, to this day, the choristers of Durham Cathedral ascend the tower, and in their fluttering white robes sing the Te Deum. This ceremony is in commemoration of the miraculous extinguishing of a conflagration on that night, A.D. 1429. The monks were at midnight prayer when the belfry was struck by lightning and set on fire; but though the flames raged all that night and till the middle of the next day, the tower escaped serious damage and the bells were uninjured-an escape that was imputed to the special interference of the incorruptible St. Cuthbert, enshrined in the cathedral. These bells, thus spared, are not those that now reverberate among the house-tops on the steep banks of the Wear. The registry of the church of St. Mary le Bow, Durham, tells of the burial of Thomas Bartlet, February 3, 1632, and adds, 'this man did cast the abbey bells the summer before he dyed.' The great bell in Glasgow Cathedral, tells its own history, mournfully, in the following inscription: 'In the year of grace, 1583, Marcus Knox, a merchant in Glasgow, zealous for the interest of the Reformed Religion, caused me to be fabricated in Holland, for the use of his fellow-citizens of Glasgow, and placed me with solemnity in the Tower of their Cathedral. My function was announced by the impress on my bosom: ME AUDITO, VENIAS, DOCTRINAM SANCTAM UT DISCAS, and I was taught to proclaim the hours of unheeded time. One hundred and ninety-five years had I sounded these awful warnings, when I was broken by the hands of inconsiderate and unskilful men. In the year 1790, I was cast into the furnace, refounded at London, and returned to my sacred vocation. Reader! thou also shalt know a resurrection; may it be to eternal life! Thomas Mears fecit, London, 1790.'. SIGNALS FOR SERVANTSThe history of the invention and improvement of the manifold appliances for comfort and convenience in a modern house of the better class, would not only be very curious and instructive, but would also teach us to be grateful for much that has become cheap to our use, though it would have been troublesome and costly to our ancestors, and looked on by them as luxurious. We turn a tap, and pure water flows from a distant river into our dressing-room; we turn another, and gas for lighting or firing is at our immediate command. We pull a handle in one apartment, and the bell rings in a far-distant one. We can even, by directing our mouth to a small opening beside the parlour fireplace, send a whisper along a tube to the servants' hall or kitchen, and thus obtain what we want still more readily. We can now scarcely appreciate the time and trouble thus saved. Hand-bells or whistles were the only signals used in a house a century and a half ago.  In an old comedy of the reign of Charles II, the company supposed to be assembled at a country-house of the better class, are summoned to dinner by the cook knocking on the dresser with a rolling pin! It was usual to call servants by ringing hand-bells; which, thus becoming table-ornaments, were frequently enriched by chasing. Walpole possessed a very fine one, which he believed to be the work of Cellini, and made for Pope Clement VII. He also had a pair of very curious silver owls, seated on perches formed into whistles, which were blown when servants were wanted. They were curious and quaint specimens of the workmanship of the early part of the seventeenth century; and one of them is here engraved for the first time, from a done sketch made during the celebrated sale at Strawberry Hill in 1842. It may be worth noting, as a curious instance of the value attached by connoisseurs to rare curiosities, that these owls were bought at prices considerably above their weight in gold; and the taste for collecting has so much increased, that there is little doubt they would now realize even higher prices. |