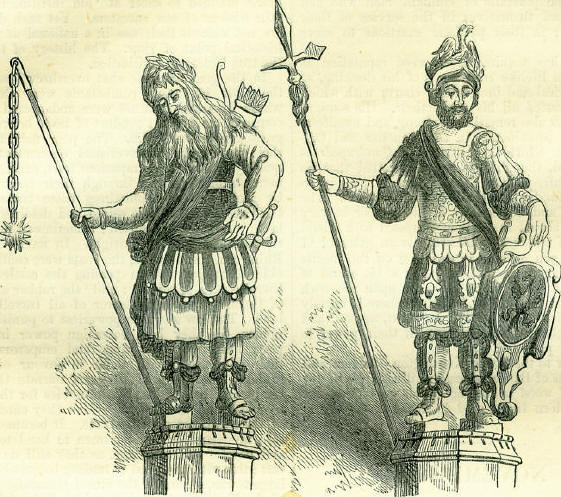

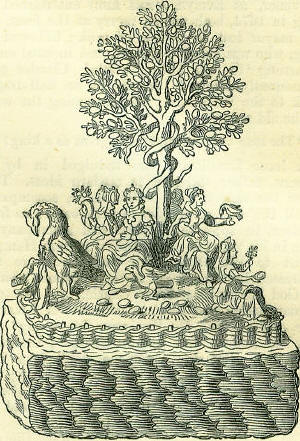

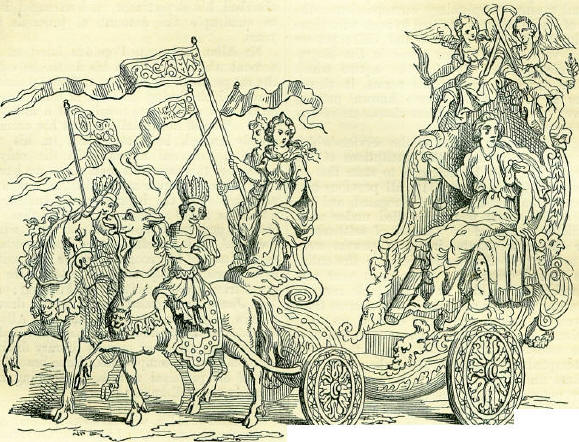

9th NovemberBorn: Mark Akenside, poet (Pleasures of Imagination), 1721, Newcastle-on-Tyne; William Sotheby, poetical translator, 1757, London. Died: William Camden, celebrated scholar, and author of Britannia, 1623, Chiselhurst; Archbishop Gilbert Sheldon, founder of the Sheldon Theatre, Oxford, 1677, Croydon; Paul Sandby, founder of English school of water-colour painting, 1809; Marshal Count de Bourmont, distinguished French commander, 1846. Feast Days: The Dedication of the Church of Our Saviour, or St. John Lateran. St. Mathurin, priest and confessor, 3rd century. St. Theodorus, surnamed. Tyro, martyr, 306. St. Benignus or Binen, bishop, 468. St. Vanne or Vitonius, bishop of Verdun, confessor, about 525. THE LORD MAYOR'S SHOWShorn of its antique pageantry, and bereft of its ancient significance, the procession that passes through London to Westminster every 9th of November, when the mayor of London is 'sworn into' office, becomes in the eyes of many simply ludicrous. It is so, if we do not cast a retrospective glance at the olden glories of the mayoralty, the original importance of the mayor, and the utility of the civic companies, when the law of trading was little understood and ill defined. These companies guarded and enforced the best interests of the traders who composed their fraternities. The Guildhall was their grand rendezvous. The mayor was king of the city, and poets of no mean fame celebrated his election, and invented pageantry for exhibition in the streets and halls, rivaling the court masques in costly splendour. Of all this nothing remains but a few men in armour, and a few banners of the civic companies, to appeal for respect in an age of utilitarianism, already too much inclined to sneer at 'old institutions' and 'the wisdom of our ancestors.' Yet such displays are not without their use in a national as well as historical point of view. The history of trade is the true history of civilization. In the great struggle that overthrew feudalism, the most important combatants were the men whose lives and fortunes were endangered in the course of the difficult conduct of trade between the great continental cities. The poor nobility, and their proud and impoverished descendants, frequently lived only by rapacious tolls, exacted from merchantmen passing through their territory, or by their castles. Sometimes these traders and their merchandise were seized and detained till a large ransom was extorted; sometimes they were robbed and murdered outright. In navigating the Rhine and the Danube, the boats were continually obliged to pay toll in passing the castles, then literally dens of thieves; and 'the robber knights' of Germany were the terror of all travellers by land. The law was then powerless to punish these nobles, for they held sovereign power in their petty territories, and kings and emperors cared little to quarrel with them in favour of mere traders. The pages of Froissart narrate the contempt and hatred felt by the nobles for the commonalty, and the jealousy which they entertained of the wealth brought by trade. It became, therefore, necessary for merchantmen to band together, and pay for armed escorts, as they still do in the east; this ultimately led to trading leagues 'between large towns, ending in the famed Hanseatic League of the North German cities, which first established trade on a secure basis, and gave to the people wealth and municipal institutions, leading to the establishment of Hotels de Ville and Mayoralties, rivaling the chateaux and stately pomp of the old nobility. The magistrates, chosen by popular voice to protect the municipality, were inaugurated with popular ceremonies; and these public celebrations occupied the same place in the estimation of the people, that the court ceremonies and tournaments did in that of the aristocracy. Ultimately, the wealthy townsmen became as proud as the nobles, and rivalled or outdid them upon all occasions where public display was considered needful. 'When sovereigns entered the cities, they were received by persons habited in classic or mythological costumes, who welcomed them in set-speeches, the invention of the best poets procurable. Elaborately decorated triumphal arches spanned the streets through which they passed; pageants, arranged on prepared stages, awaited their approach at street-corners; and on the arrival of the august guests, the characters embodied in these poured forth complimentary speeches, or sang choruses with music in their honour. The trading companies of London imitated their continental brethren in observances of the same kind. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, they rode forth in great state to meet and welcome kings or their consorts, when they came to the ' camera regis,' as they termed the city of London. Foreign potentates and ambassadors received similar honours, in order that the dignity of the city might be properly upheld. When the day came to honour their own chief magistrate, of course they were still more pleased to make public displays. Hence the mayor was inaugurated with much pomp. He went to Westminster in his gilded barge, after a noble fashion; and as he returned, he was greeted by mythological and emblematic personages stationed in pageants by the way, their speeches being prepared by civic poets-laureate, who numbered among them such men as the dramatists Peele, Dekker, Webster, Munday, and Middleton. Giants seem to have been the most general, as they were always the most popular adjuncts, to these civic displays, at home and abroad. They were intimately connected with the old mythic histories of the foundation of cities, and still appear in continental pageantry; the London giants being two ponderous figures of wood, stationary in the Guildhall. The giants of Antwerp, Douai, Ath, Lille, and other cities of the Low Countries, are from twenty to thirty feet in height, and still march in great public processions.  They occasionally unite to swell the cortege in some town, on very great occasions, except the giant of Antwerp, and he is too large to pass through any gate of the city. In English records, we read of giants stationed on London Bridge, or marching in mayoralty processions; the same thing occurring in our large provincial towns, such as Chester, York, and Norwich. In 1415, when Henry V made his triumphant entry to London, after the victory of Azincourt, a male and a female giant stood at the Southwark gate of entry to London Bridge; the male bearing the city keys, as if porter of London, In 1432, when Henry VI. entered London the same way, 'a mighty giant' awaited him, at the same place, as his champion. He carried a drawn sword, and by his side was an inscription, beginning: All those that he enemies to the king, I shall them clothe with confusion. In 1554, when Philip and Mary made their public entry into London, 'two images, representing two giants, the one named Corineus and the other Gogmagog, holding between them certain Latin verses,' were exhibited on London Bridge. When Elizabeth passed through the city, January 12th, 1558-the day before her coronation-' the final exhibition was at Temple Bar, which was 'finely dressed' with the two giants, who held between them a poetic recapitulation of the pageantry exhibited.' The earliest printed description of the shows on Lord Mayor's Day, is that by George Peele, 1585; when Sir Wolstan Dixie was installed.- The pageants were then occupied by children, appropriately dressed, to personate London, the Thames, Magnanimity, Loyalty, &c.; who complimented the mayor as he passed. One 'apparelled like a Moor,' at the conclusion of his speech, very sensibly reminded him of his duties in these words This now remains, right honourable lord, That carefully you do attend and keep This lovely lady, rich and beautiful, The jewel wherewithal your sovereign queen Hath put your honour lovingly in trust, That you may add to London's dignity, And London's dignity may add to yours. A very good general idea of these annual pageants may be obtained from that concocted by Anthony Munday in 1616, for the mayoralty of Sir John Leman, of the Fishmongers' Company. The first pageant was a fishing-boat, with fishermen 'seriously at labour, drawing up their nets, laden with living fish, and bestowing them bountifully upon the people.' These moving pageants were placed on stages, provided with wheels, which were concealed by drapery, the latter being painted to resemble the waves of the sea. This ship was followed by a crowned dolphin, in allusion to the mayor's arms, and those of the company, in which dolphins appear; and ' because it is a fish inclined much by nature to musique, Arlon, a famous musician and poet, rideth on his backe.' Then followed the king of the Moors, attended by six tributary kings on horseback. They were succeeded by 'a lemon-tree richly laden with fruit and flowers,' in punning allusion to the name of the mayor; a fashion observed whenever the name allowed it to become practicable. Then came a bower adorned with the names and arms of all members of the Fishmongers' Company who had served the office of mayor; with their great hero, Sir William Walworth, inside; an armed officer, with the head of Wat Tyler, on one side, and the Genius of London, ' a crowned angel with golden wings,' on the other. Lastly, came the grand pageant drawn by mermen and mermaids, 'memorizing London's great day of deliverance,' when Tyler was slain; on the top sat a victorious Angel, and King Richard was represented beneath, surrounded by impersonations of royal and kingly virtues.  There is still preserved, in Fishmongers' Hall, a very curious contemporary drawing of this show; a portion of it is here copied, depicting the lemon-tree; it will be perceived that the pelican (emblematic of self-sacrificing piety) is in front. At the foote of the tree sit five children, resembling the five senses,' according to the words written upon the original; to which is added the information, that this pageant 'remaineth in the Fishmongers' Hall for an ornament' during the mayoralty. Throughout the reign of James I, the inventive faculty of the city poet continued to be thus taxed for the yearly production of pageantry. When the great civil war broke out, men's minds became too seriously occupied to favour such displays; and the gloomy puritanism of the Cromwellian era put a stop to them entirely. For sixteen years no record is given of them; in 1655, the mayor, Sir John Dethick, attempted a restoration of the old shows, by introducing the crowned Virgin on horseback; in allusion to the arms of the Mercers' Company, of which he was a member. In 1657, Sir R. Chiverton restored the galley, two leopards led by Moors, a giant who walked on stilts; and a pageant, with Orpheus, Pan, and the satyrs. With the Restoration came back the old city-shows in all their splendour. In 1660, the Royal Oak was the principal feature in compliment to Charles II, and no expense was spared to make a good display of other inventions, 'there being twice as many pageants and speeches as have formerly shewn,' says the author, John Tatham, who was for many years afterwards employed in this capacity. He was succeeded by Thomas Jordan, who enlivened his pageantry with humorous songs and merry interludes, suited to Cavalier tastes. The king often came to the mayor's feast, and when Sir Robert Clayton (the 'prodigious rich scrivener,' as Evelyn terms him) entertained the king in 1674, both got so merry at the feast, that the mayor lost all notion of rank; followed the king, who was about to depart, and insisted on his returning 'to take t'other bottle.' Charles good-humouredly allowed himself to be half-dragged back to the banqueting hall, humming the words of the old song: The man that is drunk is as great as a king! A loose familiarity was indulged in by the citizens, rather startling to modern ideas. Thus, when the mayor went in his barge, accompanied by all the civic companies in their barges, as far as Chelsea, in 1662, to welcome and accompany the king in his progress down the river from Hampton Court to Whitehall, their majesties were thus addressed by the speaker in the waterman's barge: God Hesse thee, King Charles, and thy good woman there; and blest creature she is, I warrant thee, and a true. Go thy ways for a wag! thou hast had a merry time out in the west; I need say no snore! But do'st hear me, don't take it in dudgeon that I am so familiar with thee; thou mast rather take it kindly, for I am not alwayes in this good humour; though I thee thee and thou thee, I am no Quaker, take notice of that. The Plague, and the Great Fire, were the only causes of interruption to the glories of the lord mayor's show during the reign of Charles, until the quarrel broke out between court and city, which ended in the abrogation of the city charter, and the nomination of mayor and aldermen by the king. When Charles was morally and magisterially at his worst, a song was composed for the inauguration of one of his creatures (Sir W. Pritchard, 1682), declaring him to be a sovereign In whom all the graces are jointly combined, Whom God as a pattern has set to mankind. The citizens were insulted in their own hall when the king was 'pleased to appoint' Sir H. Tulsa the following year, and a 'new Irish song' was composed for the occasion, one verse running thus: Visions, seditious, and railing petitions, The rabble believe and are wondrous merry; All can remember the fifth of November, But no man the thirtieth of January. Talking of treason, without any reason, Hath lost the poor city its bountiful charter; The Commons haranguing will bring them to hanging, And each puppy hopes to be Knight of the Garter. In 1687, James II dined with the lord mayor, and introduced the pope's nuncio at the foreign ministers' table. The pageants for the day were got up, as the city poet declares, to express 'the many advantages with which his majesty has been pleased so graciously to indulge all his subjects, though of different persuasions.' The value of this author's flattery may be judged from the fact, that the song he composed in praise of James, was used in praise of William III two years afterwards, when he and his queen honoured the civic feast. In 1691, Elkanah Settle succeeded to the post of city-laureate, and contributed the yearly pageants until 1708, when the printed descriptions cease. Settle once occupied an important position in the court of Charles II, and his wretched plays and poems were preferred to those of Dryden; more from political than poetic motives. He occupies I a prominent position in Pope's Duneiad, where the glories of the mayoralty shows are said to Live in Settle's numbers one day more. This last of the city bards ultimately wrote drolls for Bartholomew Fair, and in his old age was obliged, for a livelihood, to roar in the body of a painted dragon, which he had invented for one of these shows. His works display 'a plentiful lack of wit;' but he had a sense of gorgeous display, that much pleased the populace. The pamphlet descriptive of his inventions for 1698 contains a spirited engraving of the Chariot of Justice, in which the goddess sits, accompanied by Charity, Concord, and other Virtues; the chariot being drawn by two unicorns, guided by Moors, 'sounding forth the fame of the honourable Company of Goldsmiths.' Settle generally contrived to compliment, however absurdly, the company to which the mayor belonged; and on one occasion, when a grocer was elected, introduced Diogenes in a currant-butt.  The last great show was in 1702. The mayor was then a member of the Vintners' Company, and their patron, St. Martin, appeared, and divided his cloak among the beggars, according to the ancient legend; an Indian galleon followed, which was rowed by bacchanals, and carried Bacchus on board; then came the Chariot of Ariadne; a Scene at a Tavern; and an 'Arbour of Delight,' with Satyrs carousing. It was a costly and stupid display. An entertainment was prepared for the following year, but the death of Prince George of Denmark, the husband of Queen Anne, frustrated it. The altered taste of the age, and the inutility of such displays, led to their abandonment; the land-procession being restricted to a few occasional impersonations, a few men in armour, and some banner-bearers. In 1706, the lord mayor's feast was held a few days before Christmas, and is thus described by a contemporary. The Duke of Marlborough sat on the right hand of the Lord Mayor, in the middle of an oval table, and the Lord High Treasurer on his left, and the rest of the great men according to their deserts and places. The Queen, Prince, Emperor, Duke of Savoy, and other princes allies' healths were drunk; and when the Lord Mayor offered to begin that of the Duke of Marlborough, his Grace rose up twice at table, and would not permit it till that of Prince Eugene was drunk. His Grace and the rest of the great men, so soon as dinner was over (which was about eight o'clock), took coach and returned to court. The claret that was drunk cost 1s. 6d. a bottle, and the music 50 lbs. The mayor rode on horseback in the civic procession until 1712, when a coach was provided for his use. In 1757, the gorgeous fabric which is still used on these occasions was constructed at a cost of £1065, 3s.; the panels were painted by Cipriani. Royalty generally viewed the show from a balcony at the corner of Paternoster Row, as depicted in the concluding plate of Hogarth's 'Industry and Idleness,' which gives a vivid picture of this 'gaudy day' in the city. Afterwards Mr. Barclay's house, opposite Bow Church, was chosen for the same purpose. Some few modern attempts have been made to resuscitate the old pageants. In 1837, two colossal figures of the Guildhall Giants walked in the procession. In 1841, a ship fully rigged and manned was drawn through the streets on wheels; the sailors were personated by boys from the naval school at Greenwich. But the most ambitious, and the last of these attempts, was made in 1853, when Mr. Fenton, the scenic artist of Sadler's Wells Theatre, and Mr. Cooke of Astley's, under the superintendence of Mr. Bunning, the city architect, reproduced the old allegorical cars, with modern improvements. First came a 'Chariot of Justice,' drawn by six horses; followed by standard-bearers of all nations on horseback; an Australian cart drawn by oxen, and containing a gold-digger employed in washing quartz; then came attendants carrying implements of industry; succeeded by an enormous car drawn by nine horses, upon which was placed a terrestrial globe, with a throne upon its summit, on which sat Peace and Prosperity, represented by two young ladies from Astley's. Good as was the intention and execution of this pageant, it was felt to be out of place in this modern age of utilitarianism; and this 'turning of Astley's into the streets,' will probably never be again attempted. Soon after this the city barges were sold, and the water-pageant abolished. The yearly procession to Westminster is now shorn of all dignity or significance. The banquet in Guildhall is now the great feature of the day. The whole of the cabinet ministers are invited, and their speeches after dinner are expected to explain the policy of their government. The cost of this feast is estimated at £2500. Half of this sum is paid by the mayor, the other half is divided between the two sheriffs. The annual expense connected with the office of mayor is over £25,000. To meet this there is an income of about £8000; other sums accrue from fines and taxes; but it is expected, and is indeed necessary, that the mayor and sheriffs expend considerable sums from their own purses during their year of office; the mayor seldom parting with less than £10,000. |