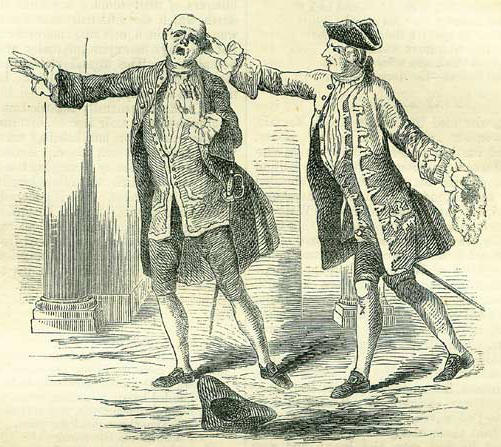

21st NovemberBorn: Edmund, Lord Lyons, British admiral, 1790, Christchurch. Died: Marcus Licinius Crassus, Roman triumvir, slain in Mesopotamia, 53 A. D.; Eleanor, queen of Edward I, 1291 A. D.; Sir Thomas Gresham, founder of the London State Papers. Feast Day: The Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. St. Gelasius, pope and confessor, 496. St. Columban, abbot and confessor, 615. SIR THOMAS GRESHAMThis eminent man was born in London in 1519, and was the second son of Sir Richard Gresham, a member of the Mercers' Company, a prosperous merchant, and lord mayor of London. Although destined for trade, young Gresham received a liberal education, and studied at Cambridge, where he was entered of Gonville College. Subsequently to this, he served an apprenticeship to his brother Sir John Gresham, also a member of the Mercers' Company. A few years after this, we find him employed by the crown in the reign of Edward VI, and afterwards in those of Mary and Elizabeth, in negotiating foreign loans. Thomas Gresham received the honour of knighthood in 1559. His enjoyment of the queen's confidence, the magnitude of his transactions, and his princely liberality, procured for him the title of the Royal Merchant; and so splendid was his style of living, that he occasionally entertained, at the queen's request, foreign visitors of high rank. Some years previous to his attainment of these honours, he had married Anne, daughter of William Ferneley of West Creting, Suffolk, then the widow of William Read, mercer, of London, by whom he had issue one child, Richard, who died at the age of sixteen in 1564. On the west side of Bishopsgate Street, in an airy and fashionable quarter, then almost in the fields, Sir Thomas Gresham built for himself a large mansion, which, with its gardens, seems to have extended into Broad Street, and to have occupied what is now the site of the Excise Office. The house was built of brick and timber, and appears to have consisted of a quadrangle enclosing a grass plot planted with trees; there were two galleries a hundred and forty feet long, and beneath them was an open colonnade. Sir Thomas destined his mansion to become a college, and to form the residence of the seven professors for whose salaries he provided by an endowment. In the Royal Exchange of London, however, he raised a more lasting memorial of his wealth and generosity. In 1566, the site on the north side of Cornhill was bought for £3500, and upon it Sir Thomas Gresham built the Exchange. Its materials, as well as its architect, are stated to have been brought from Flanders, and the Burse at Antwerp would seem to have suggested the model. The plan was a quadrangular arcade, with an interior cloister. On the Cornhill front, there was a tower for a bell, which was rung at noon and at six in the evening; and on the north side there was a Corinthian column, which, as well as the tower, was surmounted by a grasshopper the family crest. On the 23rd January 1570, Queen Elizabeth dined at Gresham's house, and visited this new building, which she was pleased to name 'The Royal Exchange.' The shops or stalls in the galleries above the cloister, and surrounding the open court, were, in Gresham's time, occupied by milliners and haberdashers (who sold mouse traps, bird cages, shoe horns, lanterns, and other heterogeneous commodities), armourers, apothecaries, booksellers, goldsmiths, and dealers in glass. The open court below must have presented a curious scene when it was filled by the merchants of different nations, in the picturesque dresses of their respective countries. On the 4th July 1575, Sir Thomas Gresham made a will whereby he bequeathed legacies to his nieces and other relations, and to several of his preantysses. He also directed black gowns, of 6s. 8d. the yard, to be given to a hundred poor men and a hundred poor women, to bring him to his grave in his parish church of St. Helen's. By another will, made on the following day, he skewed most memorably that he had never forgotten what he learned at the university, and that it was the wish of his heart to extend to others through all time the aids to learning which he had himself enjoyed. Accordingly, he bequeathed one moiety of his interest in the Royal Exchange to the Corporation of London, and the other moiety to the Mercers 'Company, and charged the corporation with the nomination and appointment of four persons to lecture in divinity, astronomy, music, and geometry. To each of these lecturers he directed an annual payment to be made of £50, and another yearly payment of £6, 13s. each, to eight almefolkes, to be appointed by the corporation, and who should inhabit his almshouses at the back of his mansion. For the prisoners in each of five London prisons, he provided the annual sum of ten pounds. The wardens and commonalty of the Mercers Company were charged: to nominate three persons to read in law, physic, and rhetoric, within Gresham's dwelling house; and out of the moiety vested in the company, to pay each lecturer £50 a year; to pay to Christ Church Hospital lately the Greyfriars, to St. Bartholomew's Hospital, to the Spital at Bedlam nere Bishopsgate Street, to the hospital for the poor in Southwark, and for the prisoners in the Countter in the Powlttrye, £10 each, annually, and to apply £100 a year, for four quarterly feasts or dynnars, for the whole company of the corporation in the Mercers Hall. The mansion house itself; with the garden, stables, and apprutenances, were vested in the mayor, commonalty, and citizens, and in the wardens and commonalty of mercers, in trust to allow the lecturers to occupy the same, and there to inhabit and study, and daily to read the several lectures. He appointed his wife executrix, in wyche behalffe (adds the testator) I doe holly put my trust in herr, and have no dowght but she will accomplishe the same accordingly, and all other things as shal be requisite or exspedieant for bothe our honnesties, fames, and good repportes in this transsitory world, and to the proffitt of the comen well, and relyffe of the carfull and trewe poore, according to the pleasseur and will of Allmyghttye God, to whom be all honnor and glorye, for ever and ever! This will was in the handwriting of Sir Thomas Gresham himself, and was proved on the 26th November 1579, five days after the testator's death. He was honourably interred in the church of St. Helen's, and there his sculptured altar tomb remains. In June 1597, the year after the death of Lady Anne, Sir Thomas's widow, the daily lectures commenced according to his will; and thenceforth, for a long course of years, his mansion house was known as Gresham College, and the chief part of the buildings were appropriated as the lodgings of the various professors. The house escaped the Great Fire of London; and when the Mansion House of London, and Gresham's Exchange, and the houses of great city companies lay in ruins after that event, Gresham College was for a time employed as the Exchange of the merchants, and afforded an asylum to the lord mayor, and the authorities of the Mercers' Company. But Gresham College acquired a more illustrious association, for it may be regarded as the cradle of the Royal Society, which, in the early part of its history, viz. from 1660 to 1710, held its meetings here, when it numbered among its associates the names of Newton, Locke, Petty, Boyle, Hooke, and Evelyn. In 1768, however, a legislative act of Vandalism put an end to the collegiate character of Gresham's foundation, and the mansion and buildings were sold to government, to form a site for the Excise Office. As compensation to the lecturers for the loss of their lodgings, their salaries were raised to £100 a year. The lectures were afterwards read for some time at the Royal Exchange, but a new college was erected and opened on the 2nd November 1843. Gresham's Royal Exchange was destroyed, as we all know, in the Great Fire. It was rebuilt on a larger scale, but similar plan. This building was accidentally destroyed by fire on the 10th January 1838, and replaced by the present stately structure which visibly perpetuates the memory of the renowned Sir Thomas Gresham. JOHN HILLBiography, combining instruction with amusement, not unfrequently exhibits, in one and the same character, examples of excellence to be fearlessly followed, and of weaknesses to be as sedulously shunned. As an instance of the advantages to be achieved by unwearied industry and rigid economy of time, the career of John Hill may be adduced as one well worthy of praise and emulation; while it also warningly spews the baleful and inevitable results of an unbridled vanity acting on a weak, malevolent, and contentious disposition. If Ishmael has his hand against every man, he must expect, as a natural consequence, that every man's hand will be against him. One of the various nicknames given to Hill by his contemporaries, was Dr. Atall, sufficiently illustrative of his character. For players, poets, philosophers, physicians, antiquaries, elides, commentators, free thinkers, and divines, were alternately selected by him as objects of satire or invective. And thus it happens, that while Hill's voluminous, and in many instances, useful works, are almost forgotten, and his valuable services to the then infant science of botany scarcely recognized at the present day, his name is principally preserved in the countless satirical squibs and epigrams launched at him by those whom he had wantonly provoked and insulted. Hill was the son of a worthy Lincolnshire clergyman, and having been educated as an apothecary, he opened a shop in St. Martin's Lane, London. Marrying before he had established a business, the res angusta domi obliged him to look for other means of support. The fame of Linnaeus, and the novelty of his sexual system of botany, then producing a great sensation throughout Europe, Hill determined to turn his attention to that science, for which he undoubtedly had a strong natural taste. Patronised by the Duke of Richmond and Lord Petro, he was employed by them to arrange their gardens and collections of dried plants. He then conceived a scheme of travelling over England to collect rare plants, a select number of which, prepared in a peculiar manner, and accompanied by descriptive letterpress, he proposed to publish by subscription. This plan failing, he tried the stage as an actor, but without success, failing even in the appropriate character of the half starved apothecary in Romeo and Juliet. Relinquishing the sock and buskin, he returned to the mortar and pestle, and while struggling for a living in his original profession, he turned his attention to literature. His first work was a translation of Theophrastus On Gems, which, being well and carefully executed, established his reputation as a scholar, and procured him fame, friends, and money. Having at last found the tide that leads to fortune, Hill was not slow to take advantage of it. He wrote travels, novels, plays; he compiled and translated with marvellous activity and industry: works on botany, natural history, and gardening in short, on every popular subject flowed, as it were, from his ready pen. From these sources he derived for several years an annual income of £1500. Obtaining a diploma in medicine from the College of St. Andrews, Hill, with this passport to society, set up his carriage, and entered on the gay career of a man of fashion. He commenced the British Magazine, and, in addition to his other labours, published a daily essay in the Advertiser, under the title of the 'Inspector.' Notwithstanding all this employment, he combined business with pleasure, by being a constant attendant at all places of public amusement, and thus procured the scandalous anecdotes which he so freely dispensed in his periodical writings. About this time he came into collision with Garrick, Hill having composed a farce called the Route, and presented it to a charitable institution as a piece written by a person of quality. The play was acted under Garrick's management, for the benefit of the charity, but received little favour; and, on the second night of its representation, it was hissed and hooted through every scene. Wild with rage and disappointment, the doctor disgorged his spite in venomous paragraphs against the manager. To which Garrick simply replied: For physic and farces, His equal there scarce is; His farces are physic, His physic a farce is! Hill returned to the attack with a paper, entitled A Petition from the Letters I and U to David Garrick. In this, these letters are made to complain bitterly of the grievances inflicted on them by the actor, through his inveterate habit of banishing them from their proper places, as in the words virtue, and ungrateful, which he pronounced vurtie and ingrateful. Garrick again replied with an epigram, in which he had decidedly the best of it: If tis true, as you say, that I've injured a letter, I'll change my note soon, and I hope for the better. May the right use of letters, as well as of men, Hereafter be fixed by the tongue and the pen; Most devoutly I wish, that they both have their due, And that I may be never mistaken for U. When all London was gulled by the story of Elizabeth Canning, Hill's natural shrewdness saw through the imposture. In a pamphlet he successfully opposed the current of popular opinion, and was, applauded by the discerning few, who had escaped that strange infatuation. One of his opponents in that and other controversies, was Henry Fielding, the goodness of whose heart made him, in this instance, the dupe of female artifice and cunning. When writing under the character of the 'Inspector,' Hill adopted a whimsically dishonest stratagem, to lash, without manifest inconsistency, some persons whom a little before he had eulogised. He published anonymously the first number of a periodical, entitled the Impertinent, in which he violently attacked the poet Smart; but took care, in the next 'Inspector' to defend him with faint praise, and rebuke the cruel treatment of him by the Impertinent. When Smart discovered this treacherous trick, he published a keen satire, entitled The Hilliad, in which he represents as follows a gipsy fortune teller inducing Hill to abandon the pestle for the pen: In these three lines athwart thy palm I see Either a tripod or a triple tree, For oh! I ken by mysteries profound, Too light to sink, thou never canst be drowned Whate'er thy end, the Fates are now at strife, Yet strange variety shall check thy life Thou grand dictator of each public show, Wit, moralist, quack, harlequin, and beau, Survey man's vice, self praised and self preferred, And be th' INSPECTOR of the infected herd; By any means aspire at any ends, Baseness exalts, and cowardice defends, The chequered world's before thee go farewell, Beware of Irishmen and learn to spell.  The allusion in the last line refers to an Irish gentleman, named Brown, who, having been libeled in the 'Inspector,' retorted by publicly beating the doctor in the rotunda at Ranelagh Gardens (see image to the right). Hill received the buffeting with humility, but to shew that such meekness of conduct was attributable rather to stoicism than to a want of personal courage, he immediately afterwards published an account of himself having once given a beating to a person, whom he named Mario. A wag, doubting this story, wrote: To heat one man, great Hill was fated. 'What man?' ' A man whom he created! Indeed, Hill did not claim for himself a high standard of truthfulness; he sometimes acknowledged in the 'Inspector' that he had told falsehoods, thus giving occasion for another epigram: What Hill one day says, he, the next, does deny, And candidly tells us it is all a lie: Dear doctor, this candour from you is not wanted For why should you own it? tis taken for granted. Hill, however, considered himself a moralist, a friend and supporter of piety and religion. He published a ponderous guinea quarto on God and Nature, written professedly against the philosophy of Lord Bolingbroke; and every Saturday's 'Inspector' was devoted to what he termed a lay sermon, written somewhat in the Orator Henley style, and affording subject matter for the following epigrammatic parody: Three great wise men, in the same era born, Britannia's happy island did adorn: Henley in care of souls, displayed his skill, Rock shone in physic, and in both John Hill; The force of nature could no further go, To make a third, she joined the former two. Rock was a notorious quack of the period. Being one day in a coffee house on Ludgate Hill, a gentleman expressed his surprise that a certain physician of great abilities had but little practice, while such a fellow as Rock was making a fortune. 'Oh!' said the quack, I am Rock, and I shall soon explain the matter to you. How many wise men, think you, are in the multitude that pass along this street? About one in twenty, replied the other. Well, then, said Rock, the nineteen come to me when they are sick, and the physician is welcome to the twentieth. And to the complexion of quackery did Hill come at last. His mind, from over production, became sterile; his slovenliness of compilation, and disregard for truth, sank his literary reputation as fast as it had risen. When his works found no purchasers, the publishers ceased to be his bankers. He had lived in good style on the malice and fear of the community, he now found resources in its credulity. He brought out certain tinctures and essences of simple plants, sage, valerian, bardana, or water dock, asserting that they were infallible panaceas for all the ills that flesh is heir to. Their sale was rapid and extensive, and whatever virtues they may have possessed, no one can deny that they were peculiarly beneficial to their author, enabling him to have a townhouse in St. James' Street, a country house and garden at Bayswater, and a carriage to ride in from one to the other. The quivers of the epigram writers were once more filled by these medicines, and thus some of their arrows flew: Thou essence of dock, of valerian, and sage, At once the disgrace and the pest of this age; The worst that we wish thee, for all of thy crimes, Is to take thy own physic, and read thy own rhymes. To this another wit added: The wish must be in form reversed, To suit the doctor's crimes, For, if he takes his physic first, He'll never read his rhymes. Hill, or some one in his name, replied: Ye desperate junto, ye great, or ye small, Who combat dukes, doctors, the devil, and all! Whether gentlemen scribblers or poets in jail, Your impertinent wishes shall never prevail; I'll take neither sage, clock, nor balsam of honey: Do you take the physic, and I'll take the money. The latter end of Hill's life was better than the beginning. Though his first wife was the daughter of a domestic servant, he succeeded in obtaining, as a second helpmate, a sister of Lord Ranelagh. At the parties of the Duchess of Northumberland, he was a frequent guest, and he acquired the patronage of the Earl of Bute. His last and most valuable work, a monument of industry and enterprise, was complete Vegetable System, in twenty four folio volumes, illustrated by 1600 copper plates, representing 26,000 plants, all drawn from nature. This work was in every respect far in advance of its period, and entailed a heavy pecuniary loss on its author. A copy of it, however, which he presented to the king of Sweden, was rewarded with the order of the Polar Star, and from thence forth the quondam apothecary styled himself Sir John Hill. Lord Bute appointed him to the directorship of the royal gardens, with a handsome salary, but it does not seem that the grant was ever confirmed. In spite of the efficacy of his Tincture of Bardana, which Hill warranted as a specific for gout, he died of that disease on the 21st of November 1775. The following is the last fling which the epigrammatists had at him: Poor Doctor Hill is dead! Good lack! Of what disorder? An attack Of gout. Indeed! I thought that he Had found a wondrous remedy. Why, so he had, and when he tried, He found it true the doctor died! MARY BERRYThis lady, who died in Curzon Street, Mayfair, on 21st November 1852, at the age of ninety, formed one of the last remaining links which connected the life and characters of the latter half of the last century with the present. Both she and her younger sister Agnes enjoyed the acquaintance and friendship of the celebrated Horace Walpole, Earl of Orford, who, after succeeding to that title, made a proffer, though an unaccepted one, of his hand and coronet to Mary Berry. These two ladies were the daughters of Mr. Robert Berry, a gentleman of Yorkshire origin, but resident in South Audley Street, London. Walpole first met them, it is said, at Lord Strafford's, at Wentworth Castle, in Yorkshire, and the friendship thus formed was a lasting one. The Misses Berry afterwards took up their abode at Twickenham, in the immediate neighbourhood of Strawberry Hill, with whose master a constant interchange of visits and other friendly offices was maintained. Horace used to call them his two wives, corresponded frequently with them, told them many stories of his early life, and what he had seen and heard, and was induced by these friends, who used to take notes of his communications, to give to the world his Reminiscences of the Courts of George I and II. On Walpole's death, the Misses Berry and their father were left his literary executors, with the charge of collecting and publishing his writings. This task was accomplished by Mr. Berry, under whose superintendence an edition of the works of Lord Orford was published in five volumes quarto. He died a very old man at Genoa, in 1817, and his daughters, for nearly forty years afterwards, continued to assemble around them all the literary and fashionable celebrities of London. Agnes, the younger Miss Berry, predeceased her sister by about a year and a half. Miss Berry was an authoress, and published a collection of Miscellanies, in two volumes, in 1844. She also edited sixty Letters, addressed to herself and sister by Horace Walpole; and came chivalrously forward to vindicate his character against the sarcasm and aspersions of Lord Macaulay in the Edinburgh Review. |