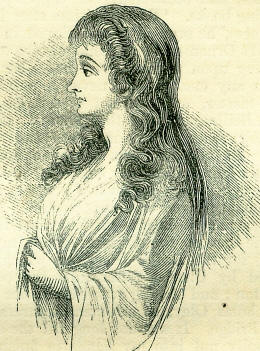

8th NovemberBorn: Edward Pocock, oriental scholar, 1604, Oxford; Captain John Byron, celebrated navigator, 1723, Newstead Abbey. Died: Pope Boniface II, 532; Louis VIII, king of France, 1226, Montpensier; Dums Scotus, theologian and scholar, 1308, Cologne; Cardinal Ximenes, governor of Spain during minority of Charles V, 1517; John Milton, great English poet and prose writer, 1674, London; Madame Roland, revolutionist, guillotined at Paris, 1793; Thomas Bewick, wood-engraver, 1828, Gateshead; George Peacock, dean of Ely, mathematician, 1858, Ely. Feast Day: The Four Crowned Brothers, martyrs, 304. St. Willehad, confessor, bishop of Bremen, and apostle of Saxony, end of 8th century. St. Godfrey, bishop of Amiens, confessor, 1118. MADAME ROLAND The terrible French Revolution brought many women as well as men into prominence-some for their genius, some for their crimes, and some for their misfortunes. Among the number was Madame Roland. She was born at Paris in 1756; her maiden name being Manon Philipon. Her father was an artist of moderate talent; her mother a woman of superior understanding and great sweetness of disposition. Manon made rapid progress in painting, music, and general literature, and became an accomplished girl. She was very religious at first, but afterwards adopted the views then so prevalent in France, and allowed her imagination to get the better of her religion. Plutarch's Lives gave her an almost passionate longing for the fame of the great men of past ages; and at the age of fourteen she is said to have wept because she was not a Roman or Spartan woman. In 1781, she married M. Roland, a man twenty years her senior, and much respected for his ability and integrity. During several years, she divided her time between the education of her young daughter, and assisting her husband in his duties as inspector of manufactures. Together they visited England, Switzerland, and other countries, and imbibed a taste for many liberal institutions and usages which were denied to France under the old Bourbon régime. At length the outburst came -the French struggle for liberty in 1789- so soon to degenerate into ruthless anarchy. The Rolands accepted the new order of things with great avidity. M. Roland was elected representative of Lyon to the National Assembly; and he and his wife soon formed at Paris an intimacy with Mirabeau and other leading spirits, at a time when the Revolution was still in its best days. There was a party among the Revolutionists, called the Girondists, less violent and sanguinary than the Jacobins; and to this moderate party the Rolands attached themselves. When a Girondist ministry was formed, Roland became Minister of the Interior, or what we should call Home Secretary. He appeared at the court of the unfortunate Louis XVI in a round hat, and with strings instead of buckles in his shoes-a departure from court-costume which was interpreted by many as symbolic of the fall of the monarchy; while his plain uncompromising language gave further offence to the court. Madame Roland assisted her husband in drawing up his official papers; and to her pen is attributed the famous warning-letter to the king, published in May 1792. It occasioned the dismissal of M. Roland from the ministry, but the dreadful doings on the 10th of August terrified the court, and Roland was again recalled to office. By this time, however, the Revolution had passed into its hideous phase; the populace had tasted blood, and, urged on by the Jacobins, had entered upon a course distasteful to the, Rolands and the Girondists generally. When the massacres of the 2nd of September took place, Roland boldly denounced them in the National Convention; but Robespierre, Marat, Danton, and the other Jacobins, were now becoming too powerful for him. Especially bitter was the wrath of these men towards Madame Roland, whose boldness, sagacity, and sarcasm had often thwarted them. The lives of herself and her husband were not considered safe; and arrangements were made for them to slip away from their regular home, the Hotel of the Interior, without making the change publicly known. But this deception was little suited to the high spirit of Madame Roland. She said on one occasion: 'I am ashamed of the part I am made to play. I will neither disguise myself nor leave the house. If they wish to assassinate me, it shall be in my own house.' The crisis came. On the 31st of May 1793, nearly forty thousand of the rabble were marched against the National Convention by the Jacobins, as the most effectual means of putting-down the Girondists. In the evening of the same day, Madame Roland was cast into prison-her husband being at the time away from Paris, for his own safety. She never again obtained her liberty, or saw her husband. Her demeanour was firm and admirable; while ardently advocating 'what she deemed reasonable individual and national freedom, she never hesitated to denounce the men who, by their sanguinary deeds, were sending a thrill of horror through Europe; but in her more silent hours she grieved for her husband and daughter, and for the many friends who were falling under the guillotine. All her jailers she converted into friends by her fascinating manner and general amiability; but they could do nothing to avert her fate. She devoted all her leisure hours in prison to the composition of her Mérnoires; in which she delineated, with much sprightliness and grace, the events of her happy youth, and with. great judgment and mournful pathos, the fearful turmoil of her later years. At one time, during her three months' imprisonment, she almost determined to take poison, like many miserable creatures around her; but her better nature came to her aid, and she resolved to meet her fate bravely. It was a horrible time. On the 16th of October, the unfortunate Marie Antoinette was guillotined. Later in the same month, twenty of the leading Girondists-all personal friends of the Rolands shared the same fate. And then came the turn of Madame Roland. After being successively imprisoned in the Abbaye, Sainte Pélagie, and the Conciergerie, she was brought to trial as an accomplice of the Girondists. A few days previous to this, Chauvieu, Madame Roland's advocate, visited her in prison, to confer respecting her defence. Interrupting him in his observations, she took a ring off her finger, and said: 'Do not come tomorrow to the Tribunal; you would endanger yourself without saving me. Accept this ring as a simple token of my gratitude. Tomorrow, I shall cease to exist.' At the trial, she appeared dressed carefully in white, with her beautiful black hair descending to her waist. Unmoved. by the insults to which she was subjected by her brutal judges, she maintained unruffled a dignity of demeanour which might have suited a Roman matron of old; but her death was a predetermined matter, and she was remorselessly condemned. On the fatal day, and at the same hour and place with herself, a man was to be guillotined. To die first on such an occasion had become a sort of privilege among the wretched victims, as a means of avoiding the agony of seeing others die. Madame Roland waived this privilege in favour of her less courageous companion. The executioner had orders to guillotine her before the man; but she entreated him not to shew the impoliteness of refusing a woman's last request. As she passed to the scaffold, she gazed on a gigantic statue of Liberty erected near it, and exclaimed: '0 Liberty! how many crimes are committed in thy name!' The guillotine then took the life of one who was, perhaps, the most remarkable woman of the French Revolution. The fate of M. Roland was scarcely less romantically tragical. He had lain concealed for some time in Rouen, but on hearing of his wife's death, he set out on the road to Paris, and walked as far as Baudouin. Here he quitted the highway, entered an avenue leading to a private mansion, and sitting down at the foot of a tree, passed a cane-sword through his body. A paper was found beside him with the following inscription: 'Whoever you are who find me lying here, respect my remains; they are those of a man who devoted his whole life to being useful, and who died as he had lived, virtuous and honest.' BEWICK, THE ENGRAVERThomas Bewick owes his celebrity to his know-ledge of animals, and the admirable manner in which he applied this knowledge to the production of illustrated works on natural history. Born at Cherryburn, in Northumberland, in 1753, he has left us in his autobiography an interesting account of his introduction to the world of art. Exhibiting some indications of taste in this direction, he was, in 1767, apprenticed to Mr. Ralph Beilby, of Newcastle-on-Tyne, an engraver of door-plates and clock-faces, and occasionally of copper-plates for illustrating books. 'For some time after I entered the business,' he says, 'I was employed in copying Copeland's Ornaments; and this was the only kind of drawing upon which I ever had a lesson given me from any one. I was never a pupil to any drawing master, and had not even a lesson from William Beilby, or his brother Thomas, who, along with their other profession, were also drawing-masters. In the later years of my apprenticeship, my master kept me so fully employed that I never had any opportunity for such a purpose, at which I felt much grieved and disappointed. The first jobs I was put to do was blocking out the wood about the lines on the diagrams (which my master finished) for the Lady's Diary, on which he was employed by Charles (afterwards the celebrated Dr) Hutton; and etching sword-blades for William and Nicholas Oley, sword manufacturers, &c., at Shotley Bridge. It was not long till the diagrams were wholly put into my hands to finish. After these, I was kept closely employed upon a variety of other jobs; for such was the industry of my master that he refused nothing, coarse or fine. He undertook everything, which he did in the best way he could. He fitted up and tempered his own tools, and adapted them to every purpose; and taught me to do the same. This readiness brought him in an overflow of work; and the workplace was filled with the coarsest kinds of steel stamps, pipe moulds, bottle moulds, brass-clock faces, door-plates, coffin-plates, bookbinders' letters and stamps, steel, silver, and gold seals, mourning-rings, &c. He also under-took the engraving of arms, crests, and cyphers on silver, and every kind of job from the silversmiths; also engraving bills of exchange, bank - notes, invoices, account-heads, and cards. These last he executed as well as did most of the engravers of the time; but what he excelled in was ornamental silver engraving. This, of course, was a strange way of introduction to the higher departments of art; but it was not a bad one for such a person as Bewick, who had the germs of a true artist within him. While we were going on in this way,' his narrative proceeds, ' we were occasionally applied to by printers to execute wood-cuts for them. In this branch my master was very defective. What he did was wretched. He did not like such jobs. On this account they were given to me; and the opportunity this afforded of drawing the designs on the wood was highly gratifying to me. It happened that one of these, a cut of the 'George and Dragon' for a bar-bill, attracted so much notice, and had so many praises bestowed upon it, that this kind of work greatly increased. Orders were received for cuts for children's books; chiefly for Thomas Saint, printer, Newcastle, and successor of John White, who had rendered himself famous for his numerous publications of histories and old ballads. . . My time now became greatly taken up with designing and cutting a set of wood-blocks for the Story Teller, Gay's Fables, and Select Fables; together with cuts of a similar kind for printers. Some of the Fable cuts were thought so well of by my master, that he, in my name, sent impressions of a few of them to be laid before the Society for the Encouragement of Arts; and I obtained a premium. This I received shortly after I was out of my apprenticeship, and it was left to my choice, whether I would have it in a gold medal or money (seven guineas). I preferred the latter; and I never in my life felt greater pleasure than in presenting it to my mother. Once favoured with the good opportunity thus afforded to him, Bewick did not fail to make use of it. Authors and publishers found him to be useful in wood engraving generally, and he earned a living at this while preparing for higher labours in art. In 1773, he engraved cuts for Dr. Hutton's Mathematics, and for Dr. Horsley's edition of Sir Isaac Newton's works. Coming to London in 1776, he executed work for various persons; but he did not like the place nor the people. Wherever I went,' he says in the work already quoted, 'the ignorant part of the Cockneys called me ' Scotch-man.' At this I was not offended; but when they added other impudent remarks, I could not endure them; and this often led me into quarrels of a kind I wished to avoid, and had not been used to engage in. It is not worth while noticing these quarrels, but only as they served to help out my dislike to London. Having returned to the north, Bewick applied himself to his favourite pursuit of designing and engraving wood-cuts in natural history, and eking out his income meanwhile by what may be termed commercial engraving. Æsop's Fables, History of Quadrupeds, History of Birds, Hutchinson's History of Durham, Parnell's Hermit, Goldsmith's Deserted Village, Liddell's Tour in Lapland-all engaged his attention by turn, whilst at the same time he employed himself in a totally different department of the engraver's art--that of executing copper-plates for bank-notes. It may be worth mentioning here, that cottages, in Bewick's early days, seem to have been adorned with large wood-cuts, as they are now with cheap coloured lithographs. I cannot help lamenting,' he observes, 'that, in all the vicissitudes which the art of wood engraving has undergone, some species of it is lost and done away. I mean the large blocks with the prints from them, so common to be seen when I was a boy, in every cottage and farmhouse throughout the country. These blocks, I suppose, from their appearance, must have been cut on the plank way on beech, or some other kind of close-grained wood; and from the immense number of impressions from them, so cheaply and extensively spread over the whole country, must have given employment to a great number of artists in this inferior department of wood-cutting; and must also have formed to them an important article of traffic. These prints, which were sold at a very low price, were commonly illustrative of some memorable exploits; or were, perhaps, the portraits of eminent men who had distinguished themselves in the service of their country, or in their patriotic exertions to serve mankind. Bewick has acquired a deserved reputation as well for the lifelike correctness of his drawing, as the allegorical and imaginative charm with which he has invested all his productions. His sense of humour was also remarkably strong, and manifests itself very prominently in the vignettes and tail-pieces with which his History of Quadrupeds is embellished, though it is to be regretted that he has not unfrequently allowed this propensity to conduct him beyond the limits of decorum. The amiability and domesticity of his temper is very pleasingly shewn in a letter, addressed to a friend in 1825, of which the following is an extract: I might fill you a sheet in dwelling on the merits of my young folks, without being a bit afraid of any remarks that might be made upon me, such as, 'Look at the old fool, he thinks there is nobody has sic bairns as he has!' In short, my son and three daughters do everything in their power to make their parents happy. A visitor to the South Kensington Museum will find a series of Bewick's designs, illustrative of the progress of wood engraving. This reviver of the art in modern times, died in 1828, at the age of seventy-six. |