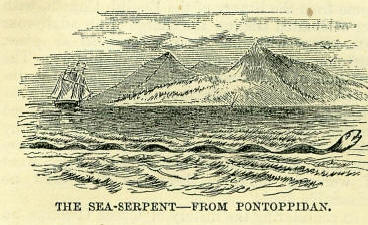

6th AugustBorn: Matthew Parker, archbishop of Canterbury, eminent divine, 1504, Norwich; Bulstrode Whitelock, eminent parliamentarian, 1605, London; Nicholas Malebranche, distinguished French philosopher (Recherche de la Veritè), 1638, Paris; Francois-de-Salignac-de-Lamothe Fenelon, archbishop of Cambray, and author of Telemnaque, 1651, Clädteau de Fenelon, Perigord; Jean Baptiste Bessières, French general, 1768, Preissac, near Cahors; Dr. William Hyde Wollaston, chemist, 1776. Died: St. Dominic de Guzman, founder of the Dominicans, 1221, Bologna; Anne Shakspeare, widow of the dramatist, 1623, Stratford-upon-Avon; Ben Jonson, dramatist, 1637, London; Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velasquez, celebrated Spanish painter, 1660, Madrid; James Petit Andrews, author of History of Great Britain, 1797, London. General Robert Cunningham, Baron Rossmore, eminent public character in Ireland, 1801. East Day: The Transfiguration of our Lord. St. Xystus or Sixtus II, pope and martyr, about 258. Saints Justus and Pastor, martyrs, 304. SHAKSPEARE'S WIFEObscure as are many of the points in Shakspeare's life, it is known that his wife's maiden name was Anne Hathaway, and that her father was a substantial yeoman at Shottery, near Stratford-on-Avon. Shakspeare was barely nineteen, and his bride about six-and-twenty, when they married. The marriage-bond has been brought to light, dated November 1582. Singularly little is known of their domestic life; and it is only by putting together a number of small indications that the various editors of Shakspeare's works have arrived at any definite conclusions concerning the family. One circumstance seems rather to tell against the supposition of strong affection on his side: Shakspeare drew out his whole will without once mentioning his wife, and then put in a few words interlined. The will points out what shall be bequeathed to his daughter Judith (Mrs. Quiney), his daughter Susanna (Mrs. Hall), his sister Joan Hart, her three sons, William, and Thomas, and Michael, and a considerable number of friends and acquaintances at Stratford; but the sole mention of Anne Shakspeare is in the item: 'I give unto my wife my second-best bed, with the furniture.' Malone accepted this interlined bequest as a proof that Shakspeare had, in making his will, forgot his wife, and then only remembered her with what was equivalent to an insult. Mr. Knight has, on the other hand, pointed out that Mrs. Shakspeare would, by law, have a third part of her husband's means; so that there was presumably the less reason to remember her with special gifts of affection. She died on the 6th of August 1623, and was buried on the 8th, in Stratford church. Her gravestone is next to the stone with the doggrel inscription, but nearer to the north wall, upon which Shakspeare's monument is placed. The stone has a brass-plate, with the following inscription: Heere lyeth interred the body of Anne, wife of William Shakespeare, who dep.ted this Life the 6th day of Avgv. 1623, being of the age of 67 Yeares. Vbera tu mater, tu lac vitamque dedisti; Yae mihi! pro tanto munere saxa dabo. Quam mallem amoveat lapidem bonus Angelus ore', Exeat [ut] Christi corpus, imago tua; Sed nil vota valent, venias cito, Christe, resurget, Clausa licet tumulo, mater, et astra petet. Mr. Knight considers this as a strong evidence of the love in which Shakspeare's wife was regarded by her daughter, with whom, he thinks it probable, she lived during her latter years. BEN JONSON Ben Jonson occupies a prominent position on the British Parnassus; yet his works are little read, because there is something of roughness and boldness in his style, which repels that class of readers who read poetry for recreation, rather than critically. But hundreds, who find little pleasure in reading his verses, feel an interest in his personal history. Jonson's poetical career was one of great activity. His was a prolific muse: his pen was seldom still. Much of his writing is lost, and yet his surviving works may be described as voluminous. All that labour which he expended in dramatic composition, in conjunction with brothers of the craft, many poems, some plays, and most of his prose, have passed into oblivion; yet there still remain to us upwards of twenty plays, about forty masques, a book of epigrams, many small poems, epistles, and translations, a book of Discoveries, as he calls a collection of prose scraps, and an unfinished Grammar of the English Language, written in English and Latin. Much of Jonson's life is involved in obscurity; partly from the usual neglect of his age in recording contemporary history, but still more from the scandals and misrepresentations of those numerous maligners, which his fame or his bluntness raised up against him. For Ben spoke out his whole mind, whether others liked it or not; and probably, like his great namesake in later times, somewhat overpowered and oppressed the lesser wits. Ben, or Benjamin Jonson, was born in Westminster, in 1574, a month after the death of his father, but his family was of Scotch extraction. They came of the Johnston of Annandale, the name having been so far changed in its migration southwards. The dramatist's mother married again, and, whatever might have been his father's position in life, his step-father was a master-bricklayer. This second parent allowed him to obtain a good education; he went to Westminster school, and in due time proceeded to Cambridge. But before he had been long at the university, the necessary funds were found wanting, and Ben returned home with a heavy heart, to become a brick-layer. This employment, of which, in after-years, he was often derisively reminded, proved uncongenial. He 'could not endure,' he tells us, 'the occupation of a bricklayer:' so he tried the military profession, and joined the army in Flanders. Before long our valiant hero sickened of the sword, and returned home, ' bringing with him,' says Gifford, ' the reputation of a brave man, a smattering of Dutch, and an empty purse.' At this critical juncture, being a good scholar, and passionately devoted to learning and literature, Jonson commenced writing for the stage. Before he had acquired any great literary notoriety, he attained to one less satisfactory, by getting into prison, for killing a man in a duel. While he remained in confinement, a priest drew him over to the Roman Catholic church, which he conscientiously persisted in for twelve years, in the meantime marrying a Roman Catholic wife. Gradually his fame became established, and for many years-after the death of Shakspeare-he retained undisputed possession of the highest poetic eminence. He grew into great favour with James I, and found constant employment in writing the court masques, and similar compositions for great occasions, which among the nobility and public 'bodies, in those days afforded occupation for the pens of poets. He also went to France for a short time in 1613, as tutor to the son of Sir Walter Raleigh, with whom, as with many other great ones, Ben lived on intimate and honourable terms. About the time of Jonson's visit to France, the king. among other proofs of kindness, made him poet-laureate, with a life-pension of a hundred marks. Learned James, Who favoured quiet and the arts of peace, Which in his halcyon-days found large increase, Friend to the humblest, if deserving, swain, Who was himself a part of Phoebus' train, Declared great Jonson worthiest to receive The garland which the Muses' hands did weave; And though his bounty did sustain his days, Gave a most welcome pension to his praise. In 1618, the poet made a pedestrian tour into Scotland, mainly, it has been surmised, to visit his friend the poet Drummond. Taylor, the so-called Water-poet, had come to Scotland at the same time on a tour, designed to prove whether he could peregrinate beyond the Tweed without money; a question which he solved in the affirmative, as the well-known Penniless Pilgrimage avouches. He found his 'approved good friend,' Jonson, living with Mr. John Stuart at Leith, and received from him a gold piece of the value of twenty-two shillings; a solid proof of the kind feelings of honest Ben towards his brethren of Parnassus. Jonson, on this occasion, spent some time with the Duke of Lennox in the west, and formed a design of writing a piscatorial play, with Loch Lomond as its scene. He passed the winter in Scotland, and in April was for three weeks the guest of Drummond at his romantic seat of Hawthornden, on the Esk. Here he drank freely-perhaps the bacchanalian habits of the north had somewhat corrupted him-indulged in the hearty egotism of a roysterer, and spoke disparagingly of many of his contemporaries, a little to the disgust of the modest Scottish poet, who took memoranda of his conversation, since published. On this subject there has been, in our day, a good deal of unnecessary discussion, to which it would be use-less further to advert. It is observable how little Jonson cared for worldly dignity. James had a wish to knight him, but he eluded the honour. He liked the love of men better. A jovial boon-companion, an affectionate friend, he was ever as open-handed as he was open-hearted. When he had money, his friends shared it, or feasted on it. Towards the close of his life, when sickness overtook him, and his popularity somewhat declined, after the death of James, he fell into poverty. He was even reduced so far as to have to ask for assistance; but he did it in a manly way. There is nothing unworthy of a man in the following letter; how superior is it to the meanness of other scribblers in those days! MY NOBLEST LORD AND BEST PATRON I send no borrowing epistle to provoke your lordship, for I have neither fortune to repay, nor security to engage, that will be taken; but I make a most humble petition to your lordship's bounty, to succour my present necessities this good time of Easter, and it shall conclude all begging-requests hereafter on the behalf of your Truest Beadsman and most Humble Servant, B. J. To THE EARL OF NEWCASTLE. The Earl of Newcastle was now Jonson's chief patron. Hearing of the poet's distress, Charles I., who had gradually taken him into favour, sent him a hundred pounds. He also willingly renewed the pension bestowed by his father, increasing the one hundred marks to one hundred pounds, adding from his own stores a tierce of Canary (Pen's favourite wine). Ben's sickness grew upon him, and he died on the 6th of August 1637, and was buried in Westminster Abbey on the 9th. The curious inscription, by which his grave was marked: 'O RARE BEN JONSON!' and which formed the concluding words of the verses written and displayed in the celebrated club-room of Ben's clique, is said to have been a temporary memorandum, until such time as a fitting monument could be erected. The story says that one of Ben's friends gave a mason, who was on the spot, eighteenpence to cut it. The troubles of the civil wars prevented the execution of a more ambitious memorial. Some have spoken of the brief legend as if it were a thing profane in that sacred place of tombs; we must confess that we think otherwise. By whatever accident or freak it came to be placed there, we fancy that it contains a true vein of pathos, and feel it to exercise a thrilling influence over us each time we look at it and read it. If Ben, by his freeness, as well as his greatness, made enemies, he secured to himself innumerable friends by the same means. No man possessed more loving friends than he among the great or among the umregarded; no man wrote more loving verses to those whom he loved. The club at the Mermaid was the meeting-place of all those brothers of song; there they held their jovial literary orgies, which have made the Mermaid a place and a name never to be forgotten. Souls of poets dead and gone, What Elysium have ye known, Happy field, or mossy cavern, Choicer than the Mermaid Tavern? So Keats expresses the unanimous feeling of all who loved Ben. Shakspeare, Sir Walter Raleigh, the learned Selden, Dr. Donne, Beaumont, Fletcher, Carew, Cotton, Herrick, and innumerable other worthies, waited religiously on the far-famed oracle; and the recollection of their meetings, and of Ben's oracular utterances, dwelt in their minds when all was over, like the remembrance of a lost Eden, as Herrick, in conclusion, shall bear witness: AN ODE FOR BEN JONSON Ah, Ben! Say how, or when Shall we thy guests Meet at those lyric feasts, Made at the Sun, The Dog, the Triple Ton? Where we such clusters had, As made us nobly wild, not mad; And yet each verse of thine Outdid the meat, outdid the frolic wine. My Ben, Or come agen, Or send to us Thy wit's great overplus: But teach us yet Wisely to husband it; Lest we that talent spend: And having once brought to an end That precious stock; the store Of such a wit: the world should have no more. A CABINET OF GEMS, FROM BEN JONSON'S DISCOVERIESVery few books contain as much wisdom in as little space as Ben Jonson's book of Discoveries. And yet, as we never hear it spoken of or quoted, it seems very clear that no one ever reads it. We grace our store-house of useful curiosities with one or two specimens of the bright golden ore hid in abundance in this unexplored mine. As the extracts are made as short as possible, the reader will observe that the words at the head of each are not always our author's, but often merely our own nomenclature for the gems in our little cabinet: DEATH OF LORD ROSSMORELord Rossmore, who, for many years in the latter part of the last century, was commander-in-chief of the forces in Ireland, died suddenly during the night, between the 5th and 6th of August 1801, at his house in Dublin, having attended a viceregal drawing-room at the Castle till so late as eleven o'clock on the preceding evening. Sir Jonah Barrington, who was Lord Rossmore's neighbour in the country, relates, in his Personal Sketches of his Own Times, an occurrence connected with his lordship's unlooked-for death, which he frankly calls 'the most extraordinary and inexplicable' of his whole existence. It may be premised that his lordship was a remarkably healthy old man, and Sir Jonah states that he ' never heard of him having a single day's indisposition.' Lady Barrington had met Lord Rossmore at the drawing-room, and received a cheerful message from him for her husband, regarding a party they were invited to at his country-house of Mount Kennedy, in the county of Wicklow. Sir Jonah. and Lady Barrington retired to their chamber about twelve, and 'towards two,' says Sir Jonah: I was awakened by a sound of a very extraordinary nature. I listened: it occurred first at short intervals; it resembled neither a voice nor an instrument; it was softer than any voice, and wilder than any music, and seemed to float in the air. I don't know wherefore, but my heart beat forcibly; the sound became still more plaintive, till it almost died away in the air; when a sudden change, as if excited by a pang, altered its tone: it seemed descending. I felt every nerve tremble: it was not a natural sound, nor could I make out the point whence it came. At length I awakened Lady Barrington, she heard it as well as myself, and suggested that it might be an Eolian harp: but to that instrument it bore no similitude: it was altogether a different character of sound. She at first appeared less affected than myself, but was subsequently more so. We now went to a large window in our bed-room, which looked directly upon a small garden underneath: the sound, which first appeared descending, now seemed obviously to ascend from a grassplot immediately below our window. It continued; Lady Barrington requested that I would call up her maid, which I did, and she was evidently much more affected than either of us. The sounds lasted for more than half an hour. At last a deep, heavy, throbbing sigh seemed to issue from the spot, and was as shortly succeeded by a sharp but low cry, and by the distinct exclamation, thrice repeated, of 'Rossmore! Rossmore! Rossmore.' I will not attempt to describe my own sensations; indeed I cannot. The maid fled in terror from the window, and it was with difficulty I prevailed on Lady Barrington to return to bed: in about a minute after, the sound died gradually away, until all was silent. Lady Barrington, who is not superstitious, as I am, attributed this circumstance to a hundred different causes, and made me promise that I would not mention it next day at Mount Kennedy, since we should thereby be rendered laughing-stocks. At length, wearied with speculations, we fell into a sound slumber. About seven the ensuing morning, a strong rap at my chamber-door awakened me. The recollection of the past night's adventure rushed instantly upon my mind, and rendered me very unfit to be taken suddenly on any subject. 'It was light: I went to the door, when my faithful servant, Lawler, exclaimed on the other side: ' Oh Lord, sir!' 'What is the matter? ' said I hurriedly. 'Oh, sir! ' ejaculated he, 'Lord Rossmore's footman was running past the door in great haste, and told me in passing that my lord, after coming from the Castle, had gone to bed in perfect health, but that, about half after two this morning, his own man, hearing a noise in his master's bed (he slept in the same room), went to him, and found him in the agonies of death; and before he could alarm the other servants, all was over! ' I conjecture nothing. I only relate the incident as unequivocally matter of fact. Lord Rossmore was absolutely dying at the moment I heard his name pronounced!' Sir Jonah was very much quizzed for publishing this story; many letters were sent to him on the subject, some of them abusing him as an enemy to religion. He consequently, in a third volume of his Sketches, published five years afterwards, thus referred to his former narration: 'I absolutely persist unequivocally as to the matters therein recited, and shall do so to the day of my death, after which I shall be able to ascertain individually the matter of fact to a downright certainty, though I fear I shall be enjoined to absolute secrecy.' It may be interesting to Scottish readers to know, that Lord Rossmore was identical with a youth named Robert Cunningham, who makes some appearance in the history of 'the Forty-five.' Having attached himself, with some other young men, as volunteers to General Cope's army, on its landing at Dunbar, he and a Mr. Francis Garden acted as scouts to ascertain the movements of the approaching Highlanders, but, in consequence of tarrying to solace themselves with oysters and sherry in a hostelry at Fisherrow, were captured by a Jacobite party. They were at first threatened with the death due to spies, but ultimately allowed to slip away, and lived to be, the one an Irish peer, the other a Scotch judge. THE SEA-SERPENTOn the 6th of August 1848, H. M. S. Dcedalus, on her way from the Cape of Good Hope to St. Helena, came near a singular-looking object in the water. Captain M'Quhae attempted to wear the ship close up to it, but the state of the wind prevented a nearer approach than two hundred yards. The officers, watching carefully through their glasses, could trace eye, mouth, nostril, and form, in the floating mass to which their attention was directed. The general impression produced was, that the animal belonged rather to the lizard than to the serpent tribe; its movement was steady, rapid, and uniform, as if propelled by fins rather than by undulating power. The size appeared to be very great; but as only a portion of the animal was above water, no exact estimate of dimensions could be made. Neither officers nor seamen ever saw anything similar to it before.  The report of this incident caused a stir among the British naturalists, who were eager to meet the popular fancy of the sea-serpent with facts shewing the extreme improbability of the existence of any such creature. Captain M'Quhae, nevertheless, insisted on the correctness of his report, and many professed to attach little consequence to the merely negative evidence brought against it. On the 12th of December 1857, the ship Castilian, bound from Bombay to Liverpool, was, at six in the evening, about ten miles distant from St. Helena. A monster that suddenly appeared in the water was described by the three chief officers of the ship-Captain G. H. Harrington, Mr. W. Davies, and Mr. E. Wheeler; the description was entered by Captain Harrington in his Official Meteorological Journal, and was forwarded to the Board of Trade. Nothing can be more plain than the honest good faith in which the narrative is written. The chief facts, in the captain's own words, are as follows: 'While myself and officers were standing on the lee-side of the poop, looking towards the island, we were startled by the sight of a huge marine animal, which reared its head out of the water, within twenty yards of the ship; when it suddenly disappeared for about half a minute, and then made its appearance in the same manner again-shewing us distinctly its neck and head, about ten or twelve feet out of the water. Its head was shaped like a long nun-buoy; and I suppose the diameter to have been seven or eight feet in the largest part, with a kind of scroll, or tuft of loose skin, encircling it about two feet from the top. The water was discoloured for several hundred feet from its head: so much so, that on its first appearance my impression was that the ship was in broken water, produced, as I supposed, by some volcanic agency since the last time I passed the island; but the second appearance completely dispelled those fears, and assured us that it was a monster of extraordinary length, which appeared to be moving slowly towards the land. The ship was going too fast, to enable us to reach the mast-head in time to form a correct estimate of its extreme length; but from what we saw from the deck, we conclude that it must have been over two hundred feet long. The boatswain and several of the crew who observed it from the top-gallant fore-castle, state that it was more than double the length of the ship, in which case it must have been five hundred feet. Be that as it may, I am convinced that it belonged to the serpent tribe; it was of a dark colour about the head, and was covered with several white spots.' Captain Harrington, some time afterwards, strengthened his testimony by that of other persons. These are but examples of many confident reports made by persons professing to have seen the sea-serpent. Between 1844 and 1846, there were reported several appearances of this monster, in the seas fronting the United States and Canada. About the same time, a similar creature was stated to have presented itself near the shores of Norway, considered as identical with one depicted in Pontoppidan's Natural History of Norway (1752), of which a transcript is here given. Twenty years earlier, the sea-serpent was repeatedly seen on the coasts of the United States, also about 1818, and in 1806. It is remarkable with what distinctness, and with what confidence, the observers state their notions of what they saw-not meaning, we suppose, to deceive, but in all good faith taking hasty and excited impressions for serious and exact observation. It chances that a creature, described by the beholders in as wonderful terms as were employed in any of the above instances, came ashore on the coast of Orkney in the year 1808. Even then exaggerated and most erroneous accounts of its decaying carcass were transmitted to scientific persons in Edinburgh, so that Dr. Barclay, the ablest anatomist of his day, was completely misled in regard to the nature of the animal. Some of the bones of the vertebral column having fortunately been sent to Sir Everard Home, in London, he was able to determine that the creature was a shark, of the species Squalus Maximus, but one certainly of uncommon size, for it had been carefully measured by a carpenter with a foot-rule, and found to be fifty-five feet long. It is not, however, the prevalent belief of naturalists, that the sea-serpent has been in all cases the Squalus Maximus. It seems to be now concluded, that the animal actually seen by M'Quhae and Harrington was more probably a certain species of seal known to inhabit the South Seas. The creature so often seen on the American coasts, was in all probability a shark, similar to that stranded in Orkney. |