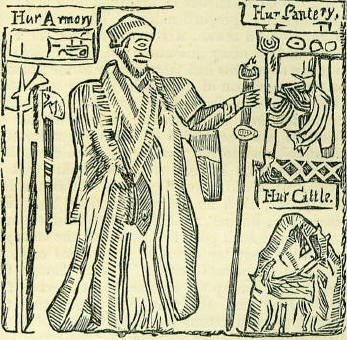

7th AugustBorn: Adam von Bartsch, engraver, 1757, Vienna; Princess Amelia, daughter of George III of England, 1783; John Ayrton Paris, distinguished physician, 1785, Cambridge. Died: Leonidas, Spartan hero, slain at Thermopylm, 480 B.C.; Herod Agrippa, persecutor of the Apostles, 44 A.D., Caesarea; Henry VI the Great, Emperor of Germany, 1106, Liege; Caroline of Brunswick, consort of George IV 1821, Hammersmith. Feast Day: St. Donatus, bishop of Arezzo, in Tuscany, martyr, 361. St. Cajetan of Thienna, confessor, 1547. QUEEN CAROLINEOn the 7th of August 1821, expired the ill-starred Caroline of Brunswick, stricken down, as was generally alleged, by vexation at being refused admission to Westminster Abbey in the previous month of July, when she desired to participate in the coronation ceremonies of her consort George IV. The immediate cause, however, was an illness by which she was suddenly attacked at Drury Lane Theatre, and which ran its course in the space of a few days. The marriage of the Prince of Wales with his cousin Caroline Amelia Elizabeth, daughter of the Duke of Brunswick, was essentially one of those unions in which political motives form the leading element, to the almost entire exclusion of personal affection and regard. By his reckless prodigality and mismanagement, he had contracted debts to the amount nearly of £650,000, after having had only a few years before obtained a large parliamentary rant for the discharge of his obligations. His father, George III, who was determined that he should contract this alliance, had engaged that, on his complying with this requisition, another application would be made to the Commons, and a release effected for him out of his difficulties. The prince, thus beset, agreed to complete the match, though he used frequently to intimate his scorn of all mariages de convénance. A more serious impediment, such as in the case of an ordinary individual, would have acted as an effectual bar to the nuptials, existed in the union which, a few years before, he had contracted with Mrs. Fitzherbert, a Roman Catholic lady, but which the Royal Marriage Act rendered in his case nugatory. This circumstance in his history was long a matter of doubt, but is now known to be a certainty. With such antecedents, it is easy to understand how his new matrimonial connection would be productive of anything but happiness. Caroline herself is said to have unwillingly consented to the match, her affections being already engaged to another, but is reported to have expressed an enthusiastic admiration of the personal graces and generous qualities of her cousin. Her portrait had been forwarded to him, and he showed it to one of his friends, asking him at the same time what he thought of it. The answer was that it gave the idea of a very handsome woman. Some joking then followed about 'buyin a pig in a poke;' but, observed the prince, 'Lennox and Fitzroy have seen her, and they tell me she is even handsomer than her miniature.' The newspapers lauded her charms to the skies, descanting on the elegance of her figure, style of dress, her intelligent eyes and light auburn hair, and the blended gentleness and majesty by which her demeanour was characterised. They also extolled her performance on the harpsichord, and remarked that, as the prince was passionately fond of music, the harmony of the pair was insured. Great talk was made of the magnificent dressing-room fitted up for the young bride at a cost of twenty-five thousand pounds, and of a magnificent cap, presented by the bridegroom, adorned with a plume in imitation of his own crest, studded with brilliants. Her journey from her father's court to England was beset by many ill-omened delays and mischances, and not less than three months were consumed from various causes on the route. On the noon of Sunday, the 5th of April 1795, she landed at Greenwich, after a tempestuous voyage from Cuxhaven. An enthusiastic ovation attended her progress to London, where she was conducted in triumph to St. James's Palace, and received by the Prince of Wales. On his first introduction to her, his nerves are reported to have received as great a shock as Henry VIII experienced on meeting Anne of Cleves, and according to a well-known anecdote, he turned round to a friend, and whispered a request for a glass of brandy. Outwardly, however, he manifested the most complete satisfaction, and the rest of the royal family having arrived to pay their respects, a domestic party, such as George III delighted in, was formed, and protracted till midnight. Three days afterwards, on the 8th of April, the marriage took place, evidently to the immense gratification of the king, who ever testified the utmost respect for his daughter-in-law, and acted through life her guardian and champion. But this blink of sunshine was destined to be sadly evanescent. The honeymoon was scarcely over ere rumours began to be circulated of disagreements between the Prince and Princess of Wales, and at the end of a twelvemonth, a formal and lasting separation took place. One daughter had been born of the marriage, the Princess Charlotte, whose untimely end, twenty-two years afterwards, has invested her memory with so melancholy an interest. The circumstances attending the disunion of her parents have never been thoroughly explained, and by many the blame has been laid exclusively on the shoulders of her husband. That he was ill fitted for enjoying or preserving the felicities of domestic life, is indisputable; but there can now be no doubt, however much party zeal may have denied or extenuated the fact, that Caroline was a woman of such coarseness of mind, and such vulgarity of tastes, as would have disgusted many men of less refinement than the Prince of Wales. Her personal habits were even filthy, and of this well-authenticated stories are related, which dispose us to regard with a more lenient eye the aversion, and in many respects indefensible conduct, of her husband. His declaration on the subject was, after all, a gentle one: 'Nature has not made us suitable to each other.' Through all her trials, her father-in-law proved a powerful and constant friend, but her own levity and want of circumspection involved her in meshes from which she did not extricate herself with much credit. On quitting her husband's abode at Carlton House, she retired to the village of Charlton, near Blackheath, where she continued for many years. Here her imprudence in adopting the child of one of the labourers in the Deptford dockyard, gave rise to many injurious suspicions, and occasioned the issue of a royal commission, obtained at the instance of the prince, for the investigation of her conduct in regard to this and other matters. The results of this inquiry were to clear her from the imputation of any flagitious conduct; but the commissioners who conducted it, passed a censure in their report on the 'carelessness of appearances' and ' levity' of the Princess of Wales. On being thus absolved from the serious charges brought against her, the paternal kindness of George III was redoubled, and he assigned her apartments in Kensington Palace, and directed that at court she should be received with marked attention. With old Queen Charlotte, however, who is said to have been thwarted from the first in the project of wedding her son to Princess Louisa of Mecklenburg, afterwards the amiable and unfortunate queen of Prussia, Caroline never lived on cordial terms. In 1814, the Princess of Wales quitted England for the continent, where she continued for six years, residing chiefly in Italy. Her return from thence in 1820, on hearing of the accession of her husband to the throne, and the omission of her name from the liturgy of the English Church, with her celebrated trial on the charge of an adulterous intercourse with her courier or valet de place, Bartolomo Bergami, are matters of history. The question of her innocence or guilt is still a disputed point, and will probably ever remain so. She was certainly, in many respects, an ill-used woman, but that the misforttmes and obloquy which she underwent were in a great measure traceable to her own imprudent conduct and want of womanly delicacy, there can also exist no reasonable doubt. In considering the history of Queen Caroline, an impressive lesson is gained regarding the evils attending ill-assorted marriages, and more especially those contracted from motives of state policy, where all questions of suitability on the ground of love and affection are ignored. As a necessary result of such a system, royal marriages have been rarely productive of domestic happiness. It is satisfactory, however, to reflect that in the case of our beloved sovereign, Queen Victoria and her family, a different procedure has been followed, and the distinct and immutable laws of God, indicated by the voice of nature, accepted as the true guides in the formation of the nuptial tie. The legitimate consequence has been, the exhibition of an amount of domestic purity and happiness on the part of the royal family of Great Britain which leaves nothing to be desired. Whilst we write, the marriage festivities of England's future king are being celebrated through the length and breadth of the land. Long may our young Prince, with the partner of his choice, enjoy that true happiness and serenity which can only spring from the union of two loving and virtuous hearts! THE FENMEMThe Fenmen, or inhabitants of the Fens lying along the east coast of England, were notorious for their obstinate opposition to all schemes of drainage. The earliest inhabitants would break down embankments, because the exclusion of the water damaged their fishing; and the more enlightened landowners of later days invariably dreaded trouble, and change, and risk of expense, more than annual destruction of property. The fact affords a curious illustration of that indolent spirit, apparently inherent in human nature, which clings, at any cost, to what is familiar. In one of those schemes for improving matters, which were set on foot from time to time, so far back as the time of the Romans, and which usually assumed considerable importance whenever a more destructive flood than ordinary had produced more than ordinary complaints, we find James I writing from Theobald's, and urging the undertakers of the work to do their utmost; describing the cause as one in which he himself was much interested, and enjoining them, among other things, to inform him of 'any mutinous speeches which might be raised concerning this business, so generally intended for the public good.' In any attempt of this kind, it seems, a fair amount of opposition was of course anticipated. On this occasion the undertakers, four in number, began operations on the 7th of August 1605, with so important a person as Sir John Popham, Lord. Chief-Justice, as one of the four; yet, although the scheme was carefully organised, and regularly arranged with the proper commissioners, the Fenmen, after all, brought it to nothing. The undertakers engaged to drain 307,242 acres, in seven years, and to accept in payment 130,000 acres, 'to be taken out of the worst sort of every particular fen proportionably.' The prospect of so handsome a reward was too much for the Fenmen; and so many grievances did they make out, so many objections had they to raise to the scheme, that a commission of inquiry had to be appointed. This commission decided against them; declaring, amongst other plain truths, that 'whereas an objection had been made of much prejudice that might redound to the poor by such draining, they had information by persons of good credit, that in several places of recovered grounds, within the Isle of Ely, &c., such as before that time had lived upon alms, having no help but by fishing and fowling, and such poor means, out of the common fens while they lay drowned, were since come to good and supportable estates.' Yet, although the king had taken up the scheme, and the good of it was self-evident, the plan duly laid, and the operations even commenced, the work had to be discontinued; chiefly because of 'the opposition which divers perverse-spirited people made thereto, by bringing turbulent suits in law, as well against the commissioners as those whom they employed therein, and making of libellous songs to disparage the work.' This instance of the Fenmen's stupid opposition was not peculiar: the following song, which went under the title of The Powte's Complaint, will afford a specimen of the 'libellous' effusions above alluded to: Come, brethren of the water, and let us all assemble, To treat upon this matter, which makes us quake and tremble; For we shall rue it, if 't be true, that the Fens be undertaken, And where we feed in Fen and reed, they'll feed both beef and bacon. They'll sow both beans and oats, where never man yet thought it, Where men did row in boats, ere undertakers bought it: But Ceres, thou behold us now, let wild-oats be their venture, Oh let the frogs and miry bogs destroy where they do enter! Away with boats and rudders; farewell both boots and skatches, No need of one nor th' other, men now make better matches; Stilt-makers all and tanners shall complain of this disaster For they will make each muddy lake for Essex calves a pasture. Wherefore let us entreat our ancient winter nurses, To shew their power so great as t' help to drain their purses; And send us good old Captain Flood to lead us out to battle, Then Twopenny Jack, with skales on's back, will drive out all the cattle. This noble captain yet was never known to fail us, But did the conquest get of all that did assail us; His furious rage who could assuage? but, to the world's great wonder, He bears down banks, and breaks their cranks and whirlygigs asunder. Great Neptune (god of seas!), this work must need provoke thee, They mean thee to disease, and with fen-water choke thee: But with thy mace do thou deface and quite confound this matter, And send thy sands to make dry lands, when they shall want fresh water. GENERAL PUTNAM'S TREATMENT OF A SPYIn the course of the transactions of the second year of the American war of independence, General Putnam caught a man lurking about his post at Peekskill, on the Hudson. A flag of truce came from Sir Henry Clinton, claiming the prisoner as a lieutenant in the British service. The answer of the old general was equally brief, and to the point: HEAD-QUARTERS, 7th August 1777. 'Edmund Palmer, an officer in the enemy's service, was taken as a spy lurking within our lines. He has been tried as a spy, condemned as a spy, and shall be executed as a spy; and the flag is ordered to depart immediately. ISRAEL PUTNAM. P. S.-He has, accordingly, been executed.' Diction somewhat similar to this regarding the treatment of an offender in Scotland fifty years earlier, is on record. It proceeded from the Earl of Islay, who ruled Scotland for Sir Robert Walpole, in the reign of George II, and was, amongst other things, an extraordinary lord of session: EDINBURGH, February 28, 1728. 'I, Archibald, Earl of Islay, do hereby prorogate and continue the life of John Ruddell, writer in Edinburgh, to the term of Whitsunday next, and no longer, by . ISLAY, I.P.D.' The letters following the signature mean, 'In presentia Dominorum,' in the presence of the Lords; i. e., the judges of the criminal court over which Islay presided; so that we must presume this trenchant rescript to have been produced in sufficiently dignified circumstances. LADY CLERK'S DREAM-STORYLady Clerk, of Penicuick, neè Mary Dacre, who spent a long widowhood in Edinburgh where some little singularities of dress made her extremely well known, used to relate (and ultimately communicated to Blackwood's Magazine) a dream-story, of the general truth of which she was well assured. It represented her father, a Cumberland gentleman, as attending classes in Edinburgh about the year 1731, and residing under the care of an uncle, Major Griffiths, of the regiment then stationed in the castle. The young man, who was accustomed to take rambles with some companions, announced to his uncle and aunt one night, that he and his friends had agreed to join a fishing party, which was to go out in a boat from Leith the next morning at six o'clock. No objection being made, they separated for the night; but during her sleep Mrs. Griffiths screamed out: 'The boat is sinking; save, oh save them!' To pursue Lady Clerk's relation: 'The major awaked her, and said, 'Were you uneasy about the fishing-party?' 'Oh, no,' she said, 'I had not once thought of them.' She then composed herself, and soon fell asleep again; in about another hour, she cried out, in a dreadful fright: 'I see the boat is going down! 'The major again awoke her, and she said: 'It has been owing to the other dream I had; for I feel no uneasiness about it.' After some conversation, they both fell sound asleep; but no rest could be obtained for her; in the most extreme agony, she again exclaimed: 'They are gone-the boat is sunk I' When the major awaked her, she said: 'Now I cannot rest: Mr. Dacre must not go, for I feel, should he go, I would be miserable till his return; the thoughts of it would almost kill me.'' In short, on the strength of this dream, Mrs. Griffiths induced her nephew to send a note of apology to his companions, who, going out, were caught in a sudden storm, and perished. Unlike many stories of the same kind, this one can be traced to an actual occurrence, which was duly chronicled in the brief records of the time. On the 7th of August 1734 (Lady Clerk's suggested date being three years too early), five men of respectable positions in life, including Patrick Cuming, a merchant, and Colin Campbell, a shipmaster, accompanied by two boys, one of whom was 'John Cleland, a nephew of Captain Campbell's,' went out in a boat with two sailors, to fish in the Firth of Forth. All was well till eleven o'clock, when a squall came on from the south-west, and they were forced to run for Prestonpans. On their way, Captain Campbell, observing a fan coming on, called to a sailor to loose the sail; but the man failed to acquit himself rightly, and the boat went over on its side. The party clung to it for a while, but one after another fell off, or sunk in trying to swim to land, all except Captain Campbell, who was taken up by a boat, and brought ashore nearly dead with fatigue, after being five hours in the water. THE WELSH MAN'S INVENTORY In one of the miscellaneous collections of the British Museum Library, there is a quaint old broadside, adorned with a coarse wood-cut, designed to burlesque the goods and chattels of a Welsh gentleman or yeoman, at the same time raising mirth at his style of language and pronunciation. It is remarkable how strong a resemblance the whole bears to the jeux d'esprit indulged in by the Lowland Scots at the expense of the simple mountaineers of the north, who are a people kindred to the Welsh. The Infentory and its quaint vignette are here reproduced: This Infentory taken Note in the Presence of hur own Cusen Rowland Merideth ap Howel, and Lewellin Morgan ap William, in 1749, upon the Ten and Thirtieth of Shun. The above-named William Morgan dyed when hur had threescore-and-twenty years, thirteen months, one week, and seven days. A Note of some Legacy of a treat deal of Goods bequeathed to hur Wife and hur two Shad, and all hur Cusens, and Friends, and Kindred, in manner as followeth: Imprimis-Was to give hur teer wife, Shone Morgan, all the coeds in the ped-room. Dealed and deilveed in the presence of Eban ap Richard ap Shinkin ap Shone hur Cusen the day and year above written London: Licensed, entered, printed, &c.' W.E. |