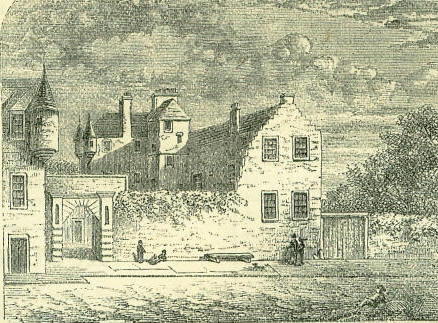

5th AugustBorn: John, Lord Wrottesley, distinguished astronomer, and president of the Royal Society, 1798. Died: Xerxes I, king of Persia, murdered by Artabanus 465 B.C.; Louis III of France, 882 A. D.; Sir Reginald Bray, architect, 1503; John, Earl of Gowrie, slain at Perth, 1600; Frederick, Lord North, statesman, 1792; Richard, Lord Howe, naval hero, 1799; Charles James Blomfield, bishop of London, 1857, Fulham. Feast Day: St. Memmius or Menge, first bishop and apostle of Chalons-sur-Marne, end of 3rd century. St. Afra and her companions, martyrs, 304. St. Oswald, king and martyr, 642. The Dedication of St. Mary ad Nives, about 435. THE ARM OF St. OSWALDIncredible sums were sometimes given by the monastic bodies, in the dark ages, for relics of saints. Amongst such valuables, the arm of St. Oswald, preserved in Peterborough Cathedral, was in especial esteem, insomuch that King Stephen once came to see it; on which occasion, besides presenting his ring, he remitted a debt of forty marks to the abbey. 'The story told of the arm is, that Oswald, who was king of Northumberland, and a very liberal benefactor to the poor, sitting at meat one day, a great number of beggars came to the gate for relief, upon which Oswald sent them meat from his own table, and there not being enough to serve them all, he caused one of his silver dishes to be cut in pieces, and distributed among the rest; 'which Aidanus, a bishop who came out of Scotland to instruct and convert these northern parts of England, beholding, took the king by the right hand, saying: Nunquam inveterascat haec manus!' Poor Oswald, however, quarrelling with one of his neighbours, Pender, king of Murcia, and encountering his army at Oswestre, or as others say at Burne, was vanquished and slain, when some, remembering Bishop Aidanus's blessing, took care to preserve his arm, which was finally treasured up at Peterborough.'-Bliss's Notes to Hearne's Diary. THE GOWRIE CONSPIRACYIt is little known that the 5th of August was once observed in England as a holiday, exactly in the same manner as the 5th of November, and for a cause of the same nature. On that day, in the year 1600, King James, then ruling Scotland alone, narrowly escaped death at the hands of two conspirators of his own people-the Earl of Gowrie, and his brother Alexander Ruthven. It was a strange confused affair, which the death of the two conspirators prevented from being thoroughly cleared up; and there have not been wanting individuals, both at the time and since, to doubt the reality of the alleged design against the king. It is, however, not difficult for an unprejudiced person to accept the conspiracy as real, and to comprehend even its scope and drift.  The king, on that August morning, was mounting his horse at Falkland, to go out a-hunting-his almost daily practice-when Alexander Ruthven, who was a youth barely twenty, came up and entered into private conversation with him. The young man told a wild-looking story, about a vagrant Highlander who knew of a secret treasure, and who might be conversed with at Gowrie House, in Perth. The king's curiosity and love of money were excited, and he agreed to go to Perth after the hunt. He then rode from the field in company with Ruthven, followed by some of his courtiers, to one of whom (the Duke of Lennox) he imparted the object in view. It appears that Lennox did not like the expedition, and he told the king so; but the king, nevertheless, proceeded, only asking the duke to have an eye upon Alexander Ruthven, to keep close, and be ready to give assistance, if needful. The king and his followers, about a dozen in number, came to Gowrie House in time for the early dinner of that age, and, after the meal was concluded, he allowed himself to be conducted by Alexander Ruthven through a series of chambers, the doors of which the young man locked behind him, till they came to a small turret closet, connected with an upper room at the end of the house, where James found, instead of the man with 'the pose' he had expected, one completely armed, a servant of the earl. Ruthven now clapped his hat upon his head, and snatching a dagger from the armed man, said to the king: 'Sir, ye maun be my prisoner! Remember on my father's deid [death]!' alluding to the execution of his father for a similar treason to this, sixteen years before. The king remonstrated, showing that he, as a minor at the time, was not concerned in his father's death, and had of his own accord restored the family to its rank and estates; and he asked meekly of the young man what he aimed at by his present proceedings. Ruthven said he would bring his brother to tell what they wanted: meanwhile the king must promise to stay quietly there till he returned. During his brief absence, the king induced the armed man to open one of the windows, looking to the neighbouring street; and while the man was proceeding to open the other, which looked to the courtyard below, Ruthven rushed in, crying there was no remede, and attempted to bind the king's hands with a garter. A struggle ensued, in which the armed servant gave the king some useful help, and James was just able to get near the window, and call out 'Treason!' It appeared from the deposition of the servant, that he had been placed there by his master, without any attempt to prepare him for the part he was to play, or to ascertain if he could be depended upon. In point of fact, the sight of the king and of Alexander Ruthven's acts filled him with terror. He opened the door, and let in Sir John Ramsay, one of the royal attendants, who immediately relieved his struggling master by stabbing Ruthven, and thrusting him down the stair. As the conspirator descended, wounded and bleeding, he was met by two or three others of the king's attendants coming up upon the alarm, and by them was despatched, saying as he fell: 'Alas! I had not the wyte [blame] of it!' Immediately after the king left the dining-room, an officer or friend of the Earl of Gowrie had raised a sudden report among the royal attendants, that their master was gone home-was by this time past the Mid Inch (an adjacent public green)-so that they all rushed forth to follow him. The porter, on being asked by some of them if the king had gone forth, denied it; but the earl called him liar, and insisted that his highness had departed. It was while they were hurrying to mount and follow, that the king was heard to cry 'Treason!' from the turret-window. The earl now drew his sword, and, summoning his retinue, about eighty in number, to follow him, he entered the house, and appeared in the room where his brother had just received his first wound. The four gentlemen of the royal train, having first thrust the king for his safety into the little closet, encountered the earl and the seven attendants who entered with him, and in brief space Gowrie was pierced through the heart by Ramsay, and his servants sent wounded and discomfited down stairs. Soon after, the Earl of Mar and other friends of the king, who had been trying for some time to force an entrance by the locked-up gallery, came in, and then James knelt down on the bloody floor, with his friends about him, and returned thanks to God for his deliverance. It was a wild and hardly intelligible scene. Gowrie and his brother were accomplished young men, in good favour at court, and popular in Perth; they had the best prospects for their future life; it seemed unaccountable that, without giving any previous hint of such a design, they should have plunged suddenly into a murderous conspiracy against their sovereign, and yet been so ill provided with the means of carrying it out successfully. Yet the facts were clear and palpable, that the king had been trained, first to their own town of Perth, and then into a remote part of their house, and there murderously assaulted. Evidence afterwards came out, to shew that they had been led to frame a plan for the seizure of the royal person, though whether for the sake of the influence they could thereby exercise in the government, or with some hazy design of taking vengeance for their father's death, cannot be ascertained. It also appeared that, at Padua University, whence they were only of late returned, they had studied necromancy, which they continued to practise in Scotland. It seems not unlikely that they were partly incited by some response, paltering with them in a double sense, which they conceived they had obtained to some ambitious question. Their attainder-nay, the attainder of the whole family-followed. The people generally rejoiced in the king's deliverance, and his popularity was manifestly increased by the dangers he had passed. Yet a few of the clergy professed to entertain doubts about the transaction; and one of eminence, named Robert Bruce, underwent a banishment of thirty years rather than give these up. His spirit has reappeared in a few modern writers, of the kind who habitually feel a preference for the side of a question which has least to say for itself. That a king, constitutionally devoid of physical courage, should have gone with only a hunting-horn hanging from his neck, and a handful of attendants in the guise of the chase, to attack the life of a powerful noble in his own house, and in the midst of armed retainers and an attached burgal populace; that he should have adventured solitarily into a retired part of his intended victim's house, to effect this object, while none of his courtiers knew where he was or what he was going to do; meets an easy faith with this party; while in the fact of Alexander Ruthven coining to conduct the king to Perth, in the glaring attempt of the earl, by false reports and lies, to send away the royal train from his house; in the fact that the two brothers and their retainers were armed, while the king was not; and in the clear evidence which the armed man of the turret-chamber gave in support of the king's statements; they can see no manner of force. Minds of this kind are governed by prejudices, and not by the love of truth, and it is vain to reason with them. LONDON SHOEBLACKSTen years before the cry of 'Clean your boots, sir!' became familiar to the ears of the present generation of Londoners, Mr. Charles Knight described 'the last of the shoeblacks,' as a short, large-headed son of Africa, rendered melancholy by impending bankruptcy, who might he seen, about the year 1820, plying his calling in one of the many courts on the north side of Fleet Street, till driven into the workhouse by the desertion of his last customer. This unfortunate was probably the individual alluded to by a correspondent of Mr. Hone as sitting under the covered entrance of Red Lion Court. He attributes the ruin of the fraternity to Messrs Day and Martin, and says he remembered the time when they were to be seen, as now, at the corner of every street. Their favourite pitches then were the steps of St. Andrew's Church, Holborn, and the site of Finsbury Square, at that period a large open space of ground. Instead of the square box used by our scarlet-coated brigade, their predecessors employed a tripod, or three-legged stool, and carried their implements in a large tin kettle. Their stock in trade consisted of an earthen-pot filled with blacking (compounded of ivory black, brown sugar, vinegar, and water), a knife, two or three brushes, a stick with a piece of rag at the end, and an old wig; the latter being used to whisk the dust or wipe the wet dirt from the shoes. The operation, in those days of shoes and shoebuckles, was one requiring some dexterity to avoid soiling the stocking or buckle. Some liberal shoeblackers, as Johnson calls them, provided an old pair of shoes and yesterday's paper for the convenience and entertainment of their patrons while the foot grew 'black that was with dirt embrowned.' The author of the Art of Living in London (1784) counsels his readers to Avoid the miser's narrow care, Which robs the shoeblack of his early fare; No-let some son of Fleet Street or the Strand, Some sooty son, with implements at hand, Who hourly watches with no other view, Than to repolish the bespattered shoe; Earn by his labour the offensive gains, Nor grudge the trifle that rewards his pains. A writer in The World for the 31st January 1754, humorously exalts the shoeblack's calling above his own. He complains that 'once an author, always an author,' is the dictum of the world- 'A man convicted of being a wit is disqualified for business during life; no city apprentice will trust him with his shoes, nor will the poor beau set a foot upon his stool, from an opinion that for want of skill in his calling his blacking must be bad, or for want of attention be applied to the stocking instead of the shoe. That almost every author would choose to set up in this business, if he had wherewithal to begin with, must appear very plainly to all candid observers, from the natural propensity which he discovers towards blackening.' Shoeblacks were also known as japanners. Pope says: The poor have the same itch; They change their weekly barber, weekly news, Prefer a new japanner to their shoes. Gay, not content with telling how The black youth at chosen stands rejoice, And 'clean your shoes' resounds from every voice, seeks to make the shoeblack of more importance, by giving him a goddess, though an unsavoury one, for a mother. According to the poet, this deity, shocked at finding her son grow up a beggar, entreated the gods to teach him some art: The gods her suit allowed, And made him useful to the walking crowd. To cleanse the miry feet, and o'er the shoe, With nimble skill the glossy black renew. Each power contributes to relieve the poor; With the strong bristles of the mighty boar Diana forms his brush; the god of clay A tripod gives, amid the crowded way To raise the dirty foot and ease his toil; Kind Neptune fills his vase with fetid oil, Pressed from the enormous whale; the god of fire, From whose dominions smoky clouds aspire, Among these generous presents joins his part, And aids with soot the new japanning art. The art, however, was scarcely new in Gay's time, for Middleton, in his Roaring Girl (1611), speaks of shoes 'stinking of blacking;' and Kitely, in Every Man in his Humour, exclaims: Mock me all over, From my flat cap unto my shining shoes. In 1851, some gentlemen connected with the Ragged Schools determined to revive the brother-hood of boot-cleaners for the convenience of foreign visitors to the Exhibition, and commenced the experiment by sending out five boys in the now well-known red uniform. The scheme succeeded beyond expectation; the boys were patronised by natives as well as aliens, and the Shoeblack Society and its brigade were regularly organised. During the Exhibition season, about twenty-five boys were kept constantly employed, and cleaned no less than 101,000 pair of boots. The receipts of the brigade during its first year amounted to £656. Since that time, thanks to a wise combination of discipline and liberality, the Shoeblack Society has gone on and prospered, and proved the parent of other societies. Every district in London now has its corps of shoeblacks in every variety of uniform, and while the number of boys has increased from tens to hundreds, their earnings have increased from hundreds to thousands. Numbers of London waifs and strays have been rescued from idleness and crime, and metropolitan pedestrians deprived of any excuse for being dirtily shod. |