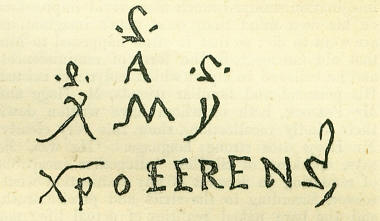

4th AugustBorn: Joseph Justus Sealiger, eminent critic, 1540, A yen, France; John Augustus Ernesti, classical editor, 1707, Tennstadt, in Thuringia; Percy Bysshe Shelley, poet, 1792, Field Place, near Horsham, Sussex. Died: Pope Martin III, 946; Henry I of France, 1060, Vitry en Brie; Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, killed at battle of Evesham, 1265; Wenceslaus V, king of Bohemia, stabbed at Olmutz, 1306; Jacques d'Armagnac, Due de Nemours, beheaded by Louis XI., 1477; William Cecil, Lord Burleigh, 1598; George Abbot, archbishop of Canterbury, 1633, Croydon; William Cave, eminent scholar and divine (Lives of the Apostles), 1713, Windsor; William Fleetwood, bishop of Ely, 1723, Tottenham; John Bacon, sculptor, 1799; Viscount Adam Duncan, admiral and hero of Camperdown, 1804; John Banim, Irish novelist, 1842, near Kilkenny. Feast Day: St. Luanus or Lugid, sometimes called Moles, abbot in Ireland, 622. St. Dominic, confessor, and founder of the Friar Preachers, 1221. ST. DOMINICThe Romish church has been for nothing more remarkable than the many revivals of energy within her pale under the impulse of particular enthusiasts. One of these took place at the beginning of the thirteenth century, through the zeal of a Spanish gentleman, named Dominic de Guzman, born at Calaruega, in Old Castile, in the year 1170. Had Dominic chosen an ordinary course of life, he would have been a man of station and dignity in the eye of the world. But, being from his infant years of a religious frame of mind, he was content to resign all worldly honour, that he might devote himself wholly to the service of God. Protestants hardly do justice to such men. Think of their objects as we will, we must own that, in confining themselves to a diet of pulse and a bed of boards, in giving away everything they had to the poor, in chastising themselves out of every earthly indulgence, and giving nearly their whole time to religious exercises, they established such a claim to popular admiration, that the influence they acquired was not to be wondered at. As an example of the self-devotion of Dominic, he offered to go as a slave into Morocco, that so he might purchase the liberation of another person. The purpose of all his devotions was to secure the eternal welfare of others. It was the 'Waldensian heresy' that first put him into great activity. His success in restoring many of the Vaudois to the church seems to have suggested to him that he, and others associated with him, might greatly advance the interests of religion by a practice of going about preaching and praying continually, while at the same time visibly abstaining in their own persons from every sort of indulgence. In the course of a few years, he had thus established a new order of religious called the Black or Preaching Friars, or shortly, from his own name, the Dominicans (the term black referred to the hue of the cloak and hood which they wore). This order was sanctioned by Pope Innocent III in 1215, and very soon it had its establishments in most European countries. There were in England, at the Reformation, forty-three monasteries of Blackfriars, and in Scotland fifteen. Dominic was unremitting in his exertions to extend, sustain, and animate his institution. He performed many journeys, always on foot, and on bare feet. He braved every sort of danger. He never shewed the slightest symptom of pride in his success: all with him was for the glory of God and the saving of men. The contemporary memoirs which describe his life are full of miracles attributed to him. He on several occasions restored to life persons believed to be dead. Often, in holy raptures at the altar, he appeared to the bystanders elevated into the air. It was his ardent desire to shed his blood for the cause he had espoused; but in this he was not gratified. The founder of the Dominicans calmly expired of a fever at Bologna, at the age of fifty-one. He was canonized by Gregory IX in 1234. SIMON DE MONTFORTSimon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester-the Cromwell of the thirteenth century-was a French noble possessed of English property and rank through his mother. We know little of the early years he spent in France; but, after establishing himself at the English court, he soon comes into notice. By the favour of the young king, Henry III, he was united to the monarch's widowed sister Eleanor, notwithstanding a difficulty arising from a vow of the lady's never to wed a second husband. This marriage involved De Montfort in many troubles, and lost him, for a time, the friendship of the king. After a temporary absence from England, he returned to raise the means of going on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Duly provided, he journeyed to Syria, where he greatly distinguished himself by his military talents and achievements, and became extremely popular with the Christians. He returned to England in 1241, and appeared to have recovered all the favour at court which he had formerly enjoyed. In 1242, he distinguished himself in the war against the French. But he had now become well known as a political reformer, and as a champion of popular liberties; and it is not improbable that his known principles had been partly the means of raising him enemies at court. His name stood second among the signatures to the bold remonstrance against papal extortion and oppression in 1246, and in 1248 the king was driven by his remonstrances into a temporary fit of economy. Earl Simon had formed a design to return to the Holy Land, but King Henry, embarrassed at this time by the turbulence of his subjects in Gascony, persuaded him to remain and undertake the government of that country, where he soon reduced the rebels to submission. In consequence of King Henry's imprudence, the rebellion broke out with more fury than ever, and it not only required all the earl's military talents to suppress it a second time, but he was obliged to raise money on his own estates to carry on the war, in consequence of the miserable condition of the royal treasury. The rebel leaders now sought to injure in another way the governor with whom they could no longer contend openly, and they sent a deputation to England, to accuse him to the king of tyranny and extortion in his administration-charges which seem, if true at all, to have been excessively exaggerated. Yet the king listened to them eagerly, and when Earl Simon arrived at court to plead his own cause, a violent scene took place, which shewed that the king could lose his dignity as easily as the earl his temper, and they were only reconciled by the interference of Prince Richard and the Earls of Gloucester and Hereford. From this moment the king no longer disguised his hatred to Simon de Montfort. Nevertheless, the latter consented to resume the command in Gascony, where he found affairs in greater confusion than ever. He was proceeding to execute his difficult task with his usual ability, when the king sent directions to his subjects in Gascony not to obey him, and appointed his young son, Edward, to govern in his stead. When the earl became aware of this treacherous conduct, he left Gascony and repaired to Paris, where he was held in such esteem that the regency of France, in the absence of its king, was offered him. But he remained steady in his duties to his adopted country, declined this great honour, and soon afterwards, when Gascony was nearly lost by the misconduct of King Henry's officers, he voluntarily offered his services in restoring it, which were gladly accepted. When the province was by his means reduced to obedience and order, the earl, now reconciled with the king, returned to England, where King Henry's misgovernment had brought the kingdom to the eve of a civil war. Such were the antecedents of the great baron who was now to assume a still more exalted character. The events of the Barons' War are given in every history of England, and can only be told very briefly here. At the parliament of Oxford in 1258, the barons of the popular party overpowered the court, and compelled the king to consent to statutes which took the government out of his hands and placed it in those of twenty-four persons, twelve of whom were to be chosen by each of the two parties. The first name on the baronial list was that of Simon de Montfort, whom the barons now looked upon as their leader. The insolent and oppressive foreigners, who, under Henry's favour, had eaten up the land, were now driven out of England, and the government was carried on with a degree of justice and vigour which was quite new. The king, meanwhile, was behaving basely and treacherously, and he had taken steps to induce the pope not only to absolve him from all oaths he had taken, or might take, but to interfere in his favour in a more direct manner. The pope's brief arrived in 1261, when the king, whose friends had gained over some of the less patriotic of the barons, ventured to throw off the mask, and proclaimed all to be null and void which had been done since the parliament of Oxford. The result of all this, after two or three years of turbulence and confusion, was the great battle of Lewes, Wednesday, May 14, 1264, in which the barons, under the command of Simon de Montfort, obtained so sanguinary and decisive a victory, that the king, his son Edward (afterwards Edward I), and the king's brother, Richard, King of the Romans, remained among the prisoners, and the royal cause was for the time utterly ruined. The principles now proclaimed by Earl Simon and the barons, involved principles of political freedom of the most exalted character; which we can only understand by supposing that they were founded partly on older Anglo-Saxon sentiments, and that they were moulded under the influence of men of learning who had studied not in vain the writers of the classic ages. A rather long Latin poem, written by one on the baronial side soon after the battle of Lewes, and intended, no doubt, to be recited among the clergy of that party, who were very numerous, in order to keep constantly before their minds the principles which the barons fought for, gives a complete exposition of the political doctrines of what we may call the constitutional party of the middle of the thirteenth century, and they are doctrines of which we need not be ashamed at the present day. This curious poem, which is printed in Mr. Wright's Political Songs (published by the Camden Society), lays it down very clearly, that the king derives his power from the people; that he holds it for the public good; and that he is under control, and responsible for his actions. Even feudalism is totally ignored in it, and it was the plebs plurima, the mass of the people, for whom Earl Simon and his barons fought, it was salutem communitatis, the weal of the community, he sought, and the king's defeat was a just judgment upon him, because he was 'a transgressor of the laws.' 'For,' we are here told, 'every king is ruled by the laws.' The nobles are spoken of as placed between the people and the king as guardians of their liberties, to watch over the exercise of the royal power and prevent its abuse. ' If the king should adopt measures destructive to the kingdom, or should nourish the desire of setting his own power above the laws-if thus or otherwise the kingdom should be in danger-then the magnates of the kingdom are bound to look to it, ' that the land be purged of all errors.' The constraint to which a king is rightly subjected, is only a just power held over him to prevent his doing wrong, or choosing bad ministers-it is not making him a slave. 'He who should be in truth a king,' the poem says, 'he is truly free if he rule rightly himself and the people; let him know that all things are permitted him which are in governing convenient to the kingdom, but not such as are injurious to it. It is one thing to rule according to a king's duty, and another to destroy by resisting the law.' 'If,' it goes on to say, 'a king is less wise than he ought to be, what advantage will the kingdom gain by his reign? If he alone has the right to choose, he will be easily deceived, since he is not capable of knowing who will be useful. Therefore, let the community of the kingdom advise; and let it be known what the generality thinks, to whom their own laws are best known ... it concerns the community to see what sort of men ought justly to be chosen for the utility of the kingdom It is a thing which concerns the whole community, to see that miserable wretches be not made the leaders of the royal dignity, but that they be good and chosen men, and the most approved that can be found.' In accordance with these sentiments, a summons was issued, dated from Worcester, on the 14th of December 1264, calling a parliament to meet on the 20th of January following, addressed to the barons, both lay and ecclesiastic, and two representatives from each county. Ten days later, on the 24th of December, new writs were issued, calling upon each city and town in the kingdom 'to choose and send two discreet, loyal, and honest men,' to represent them in the same parliament. This second summons was dated from Woodstock, and is the first instance in which the commons, properly speaking, were ever called to sit in an English parliament. If there were nothing else for which we have reason to be grateful to Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, we certainly have reason to be thankful to him for laying the foundation of the English House of Commons. This great revolution was too advanced for an age in which feudalism, though in a weakened form, was established in our island, and physical force was distributed into too few hands to remain united. Success only made place for personal jealousies, and selfish motives led many of the barons to desert the popular cause, while others were quarrelling among themselves. A succession of intrigues followed, and new leagues were formed among the barons, until, on the 4th of August 1265, the decisive battle of Evesham was fought, in which Simon de Montfort was slain, and the barons sustained a ruinous defeat. The joy of the royalists was shewn in the indignities which they heaped upon the body of the great statesman, but his work remained, and none of the substantial advantages of the baronial war of the middle of the thirteenth century have ever been lost. The short period of the battles of Lewes and Evesham stands as a marked division between two periods of English constitutional history. CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUSAt the hour of eight, on the morning of Friday, 3rd of August 1492, Columbus, with his little squadron of three ships, sailed from the port of Palos, in Spain, with the object of reaching India by a westerly course. The result of this voyage was, as is well known, the discovery of the continent now termed America; and thus the remarkable prediction of the old pagan philosopher and poet, Seneca, was almost literally fulfilled: Venient annis secula seris, Quibus Oceanus vincula rerum Laxet, et ingens pateat tellus, Tethysque novos detegat orbes; Nee sit terris ultima Thule. The life and voyages of Columbus, being matters of history, are without the pale of our limited sphere. It is not generally known, however, thata very obscure point in the history of his first voyage, has lately been most satisfactorily cleared up, Captain Becher, of the Royal Navy, aided by the practical skill of a thorough seaman, and the scientific acquirements of an accomplished hydrographer, having clearly proved that Watling's Island, one of the Bahamas, was the first land, in the New World, seen by Columbus, and not the Island of Guanahini, as had previously been generally supposed. The precise meaning of the curious form of signature, adopted by the great navigator, is still a subject for doubtful speculation; that he himself considered it to be of weighty importance, is evident from the following injunction in his will: 'Don Diego, my son, or any other, who may inherit this estate, on coining into possession of the inheritance, shall sign with the signature which I now make use of; which is an S, with an X under it, and an M, with a Roman A over it, and over that an S, and a great Y, with an S over it, with its lines and points as is my custom, as may be seen by my signature, of which there are many, and it will be seen by the present one. He shall only write The Admiral, whatever titles the king may have conferred upon him. This is to be understood, as respects his signature; but not the enumeration of his titles, which he can make at full length if agreeable; only the signature is to be The Admiral'-El Almirante. The signature thus specified, is the following:  The Xpo, signifying Christo, is in Greek letters; and, indeed, it is not unusual at the present day, in Spain, to find a mixture of Greek and Roman letters and languages in signatures and inscriptions. This signature of Columbus exemplifies the peculiar character of the man, who, considering himself selected and set apart from all others, by the will of Providence, for the accomplishment of a great purpose-great in a temporal, greater still in a spiritual point of view-adopted a correspondent formality and solemnity in all his actions. Named after St. Christopher, whose legendary history is comprised in his name Christophorus-the bearer of Christ-being said to have carried the infant Saviour on his shoulders over an arm of the sea-Columbus felt that he, too, was destined to carry over the sea the glad tidings of the gospel, to nations dwelling in the darkness of paganism. Spotorno, commencing with the lower letters of the mysterious signature, and connecting them with those above, conjectures them to represent the words Xristus Sancta Maria Josephus. Captain Becher, however, has given a much simpler, and, in all probability, the correct solution of the enigma. It was from Queen Isabella that Columbus, after many disappointments, first received the welcome intelligence, that he should be sent on his voyage, and that his son would be received into the royal service during his absence. Moved to tears of joy and gratitude at the prospect of realising the grand object of his life, and the advancement and protection offered to his son, the great man, as soon as his feelings allowed utterance, exclaimed: ' I shall ever be the servant of your majesty!' We may readily believe that Columbus would retain this sentiment of devoted service, and bequeath it as a sacred heir-loom to his successors; and assuming that the concealed words are Spanish, and the letters are to be read in their regular order, they, in all probability, signify: SERVIDOR SUS ALTEZAS SACRAS JESUS MARIA ISABEL. Or iii English and in full: THE SERVANT OF THEIR SACRED HIGHNESSES JESUS MARY AND ISABELLA, CHRIST BEARING. THE ADMIRAL. SHELLEYIt would be difficult to point out a career, as recent and familiar to us as that of Shelley, involved in so many obscurities. From some peculiar bias of temperament, or constitutional irregularity, his imagination stamped much more vivid impressions on his own mind than most men's imaginations are wont to do; so that it often happened to him that old fancies took the form of reminiscences, and he believed in a past which had never existed. His personal and familiar friends, Mr. Hogg and Mr. Peacock, both of whom have written down their kindly recollections, skew this very clearly. Mr. Hogg uses strong language. 'He was,' he says, speaking of Shelley, 'altogether incapable of rendering an account of any transaction whatsoever, according to the strict and precise truth, and the bare naked realities of actual life; not through an addiction to falsehood, which he cordially detested, but because he was the creature -the unsuspecting and unresisting victim-of his irresistible imagination. Had he written to ten different individuals the history of some proceeding in which he was himself a party and an eye-witness, each of his ten reports would have varied from the rest in essential and important particulars.' Though this statement looks somewhat exaggerated, Mr. Peacock, who quotes it, does not contradict it, and many of his anecdotes go to shew that it is, in the main, true; and the result is, that many stories, confidently reported-many tragic histories of nightly attempts to assassinate the poet, or mysterious visitants to his abode, or singular events in his ordinary life, resting only on his own testimony-will have to be quietly, though often, doubtless, reluctantly, passed over by a cautious biographer. Concerning Shelley, already much error has been corrected, and probably more remains to correct; even as many more particulars have still to be revealed. Strictly speaking, Shelley's life is still unwritten, and at present it will remain so, though the leading events are well known. Percy Bysshe Shelley came of an aristocratic stock. At the time of his birth, the 4th of August 1792, his grandfather was a baronet, and before Shelley was many years old, his father succeeded to the title, as also did. Shelley's son, Sir Percy, after the poet's death. At ten years old, he was sent to Zion House Academy, near Brentford, and in his fifteenth year he went to Eton. Being of a sensitive nature, he had to pass through many troubles, and his eccentricities brought him into more, before he had been at Oxford many terms. He and Mr. Hogg, a college-friend, concocted a little pamphlet on religious subjects, and printed it for private circulation; and the master and fellows of University College saw good, in a fit of rigid orthodoxy, to expel both of them. Men who think little are often severely orthodox, but deep thinkers are mostly lenient towards the scruples of others. Nevertheless, we must admit that Shelley went far enough to startle more than mediocrity. Even at Zion House Academy he was given to raising the devil, and throughout his life he remained, let us say, a philosopher. That earnestness and love of truth which made comedy repulsive to him, conspired, with independent and original thinking, to make him very fearless in expressing and maintaining his many eccentric opinions. Young thinkers are generally sanguine and self-important; they seem to fancy that the world never existed till they themselves set eyes on it, and deem them-selves inspired apostles specially raised up to set truth on its feet again. Shelley's circumstances, after his expulsion from Oxford, became straitened. His father, who was never kind to him, refused supplies, and he had to live on secret remittances from his kind-hearted sisters. They sent them to his lodging in London by the willing hand of a school-fellow, Harriet Westbrook, and the sympathy she shewed won the heart of the grateful youth. The two children, as we may call them, came to an understanding, and eloped to Scotland, and their marriage-ceremony was performed at Edinburgh in August 1811, Shelley being nineteen, and his wife not so old. Matters went on pleasantly for a time, and Harriet Shelley made an affectionate wife; but she did not prove exactly the partner fully to correspond to her husband. Love cannot do all the household-work, but requires some handmaidens. There was still a void, as the future revealed, ungraciously enough. Shelley did not allow it to himself, and in 1814, the marriage-ceremony was performed again, according to the English form; but soon afterwards he met with Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, and the strong current of his feelings changed. Mary Godwin was a woman of great intellectual energy and congenial tastes; and so, at once-let no man judge him!-he left his wife without her consent; he left her sister, whom he disliked intensely; and his children, whom he loved to carry in his arms, singing a strange lullaby of 'Ya'hmani, Ya'hmani, Ya'hmani, Ya'hmani;' and went abroad with the other lady. Harriet drowned herself in the Serpentine two years later, and Miss Godwin became Mrs. Shelley. Shelley's children by his first wife were taken from him, on the plea that their father held, and acted upon, opinions with respect to marriage 'injurious to the best interests of society.' It is not correct, as usually stated, that this deprivation was made because of his heterodox religious opinions. His first wife's tragical end, as well as the loss of his little ones, affected Shelley with the most lively grief; although the same considerations, which will make many readers smile at the statement, sealed his lips. Much of the rest of Shelley's short life was spent in Italy. His father had finally arranged to allow him a thousand a year, so that anxiety on that score was taken away. Surrounded with the grand features and exquisite beauties of prodigal nature, he fed the unceasing stream of his spiritual fancy, and filled the world with the luxurious music of strains, wild as Anion's; all the time drawing visibly nearer-so say some who knew him, though. not all-to the evident catastrophe, premature death. Inevitable as early death was to his failing constitution, it came before the expected time; for a squall sank his boat in the bay of Spezzia, and the waves received him, together with his friend, Captain Williams. After long search, the bodies were found and burned-that of Captain Williams on August 15, 1822, and that of Shelley on the following day-according to the requirements of quarantine regulations. Byron, Leigh Hunt, and Trelawny performed the last obsequies, and Trelawny and Hunt have left us an account of them. His ashes were interred in the Protestant cemetery at Rome. Shelley had three children by his second wife; William and Clara, who died before him, and the one who was afterwards Sir Percy. Mrs. Shelley survived him many years, and lived to publish his Memorials. The poet's lines on his little boy are worthy of a place in this brief sketch: TO WILLIAM SHELLEY (With what truth I may say- Roma! Roma! Roma! Non 'e piu come era prima!) My lost William, thou in whom Some bright spirit lived, and did That decaying robe consume Which its lustre faintly hid, Here its ashes find a tomb, But beneath this pyramid Thou art not-if a thing divine Like thee can die, thy funeral shrine Is thy mother's grief and mine. Where art thou, my gentle child? Let me think thy spirit feeds, With its life intense and mild, The love of living leaves and weeds, Among these tombs and ruins wild; Let me think that through low seeds Of the sweet flowers and sunny grass, Into their hues and scents may pass A portion' Let the reader decide why the verse is left unfinished. A familiar acquaintance existed between Shelley and Byron. They made an excursion together round the Lake of Geneva, and afterwards saw a great deal of each other in Italy. Shelley believed implicitly in Byron's genius, yet their natures were not, in many respects, congenial. Byron was a problem to Shelley, and sometimes a source of amusement. We meet with a playful instance of his quiet sarcasm in a letter to Peacock, written in August 1821, which will also afford a curious illustration of their manner of life: 'Lord Byron gets up at two. I get up, quite contrary to my usual custom, but one must sleep or die, like Southey's sea-snake in Kehama, at twelve. After breakfast, we sit talking till six. From six till eight we gallop through the pine-forests which divide Ravenna from the sea; then come home and dine, and sit up gossiping till six in the morning. I do not think this will kill me in a week or fortnight, but I shall not try it longer. Lord B.'s establishment consists, besides servants, of ten horses, eight enormous dogs, three monkeys, five cats, an eagle, a crow, and a falcon; and all these, except the horses, walk about the house, which every now and then resounds with their unarbitrated quarrels, as if they were the masters of it .... P.S.-After I have sealed my letter, I find that my enumeration of the animals in this Circean palace was defective, and that in a material point. I have just met on the grand staircase five peacocks, two guinea-hens, and an Egyptian crane. I wonder who all these animals were before they were changed into these shapes.' A most brotherly and affectionate friendship existed between Shelley and Leigh Hunt. Leigh Hunt went to Italy at Shelley's instigation, to share in the preparation of a quarterly magazine-The Liberal-which Shelley, Byron, and Hunt were mainly to support: he lost his friend soon after his arrival. Leigh Hunt well knew-knew perhaps better than any one-the generous, kind, and noble, and loving nature so tragically taken from the earth. Shelley was a genius in the highest sense of the word. His spiritual, impressible soul was little fitted to be penned up in a common-place world. Though he lived but a brief period, his pen was prolific, wild, and musical, beyond anything written since, if not before. His poems will maintain a place in the literature of his country, although, from their subtlety, and their philosophic tendency, many of them are tiresome to read, and will remain unread except by a few. His earliest effort, Queen Mab, was inspired by Southey's Thalaba, and contains much speculative matter. The Revolt of Islam is his longest poem: it met with virulent censure in its first form, and under its earlier title of Lam and Cythna. The Cenci was one of the few productions of his pen which were popular in his own time. A drama, harrowing in its details, taking for its subject the horrible story of Beatrice Cenci, it is less mystical than most of Shelley's writings, and possesses more human interest, though it cannot be considered in any sense fit for the stage. The Adonais, or lament for Keats, is a favourite with every one; and many of his smaller poems, such as The Skylark, The Invitation, and others, figure in every selection of English poetry. Had he lived longer, it is more than probable he would have acquired a firmer tone, and a more popular and enduring manner. We may append, in conclusion, Shelley's own lines: Music, when soft voices die, Vibrates on the memory Odours, when sweet violets sicken, Live within the sense they quicken. Rose leaves, when the rose is dead, Are heaped for the beloved's bed; And so thy thoughts, when thou art gone, Love itself shall slumber on. It would not be right to omit Robert Browning's beautiful tribute to the memory of the poet: Memorabilia Ah, did you once see Shelley plain, And did he stop and speak to you? And did you speak to him again? How strange it seems, and new! But you were living before that, And you are living after, And the memory I started at My starting moves your laughter! I crossed a moor with a name of its own, And a use in the world, no doubt, Yet a hand's-breadth of it shines alone 'Mid the blank miles round about For there I picked up on the heather, And there I put inside my breast A moulted feather, an eagle feather- Well, I forget the rest. ARCHBISHOP ABBOT'S LAST HUNTOn the 4th of August 1621, Mr. John Chamberlain writing, as he was accustomed to do, to Sir Dudley Carleton, adverted to a strange accident which had just fallen out in the hands of the Archbishop of Canterbury (George Abbot). In those days, when hunting was the favourite and almost the only amusement of the English nobility, the gay train of huntsmen, falconers, verderers, and rangers seldom left the courtyard without ecclesiastics among them. The purity of ' the cloth' was not thought to be in the least stained by partaking in such sport. Even the Arch-bishop of Canterbury of the time above indicated-all Calvinist as he was-did not scruple to join in the pleasures of the chase. He was now on the borders of sixty, and his declining health made such recreation the more desirable. Paying a visit to Lord Zouch, at his seat of Bramshill, in Hampshire, the archbishop accompanied a hunting party to the field, furnished with a cross-bow, the weapon then usually employed against deer. A buck being started, his Grace discharged an arrow, which, instead of hitting the animal, struck the arm of Peter Hawkins, one of Lord Zouch's gamekeepers. An artery was divided, and the poor man bled to death in half an hour, to the inexpressible grief and distress of the archbishop, although the bystanders acquitted him of everything save awkwardness. His Grace made all the reparation in his power by settling an annuity on the widow and children of the deceased. He also thenceforth held a monthly fast on account of the sad event. Casualty as the act obviously was, there were not wanting some who urged that the archbishop should be tried for it as a crime. King James knew too well the chances of the hunting-field to allow of any such course being taken. He remarked that he had once himself shot a keeper's horse under him; the queen, too, had on another occasion killed him one of the best braches (hounds) he ever possessed. It was a mere misfortune which might befall any man. In this light the accident was viewed by the inquest held on the body of Hawkins; nay, in their verdict, they found that the man's death came 'per infortunium suâ propriâ culpâ' It was, nevertheless, an accident not easily to be passed over in an archbishop. Many doubted if, with blood on his hands, he could henceforth exercise the functions of a prelate. To settle this point, a mixed commission was appointed by the king, and this court sat five months deliberating on the many subtleties connected with the question, at length pronouncing that the archbishop required both a royal pardon, and a re-instatement in his metropolitan authority. After all this was done, Laud and three other clergymen, elected to bishoprics, refused to accept consecration from Abbot, and the rite was accordingly performed by a congregation of prelates in the Bishop of London's chapel. There can be little doubt that dislike for the archbishop's puritanic leanings actuated these scrupulous divines fully as much as a horror for the blood of Hawkins. Archbishop Abbot was of humble extraction, his father being a cloth-worker at Guildford, in Surrey. It is told that his mother, a short while before his birth, dreamed that if she could have a pike or jack to eat, the baby she was expecting would rise to greatness. Some time after, fetching water from the river, a jack came into her pail, which she immediately cooked and ate. Some persons of rank hearing of this, offered themselves as sponsors to the child; and a gentleman one day passing over Guildford Bridge, noticed George and his brother Robert playing, and struck with their appearance, offered to put them to school, and then sent them to the university. In 1599, George was installed Dean of Winchester; ten years after, advanced to the see of Lichfield, thence to London, and the year after to the Primacy. He took a leading part in completing the Reformation; assisted materially in the translation of the Bible; counselled his king wisely in many difficult matters; opposing him fearlessly in his declaration of sports and pastimes on Sunday, and in the divorce which was granted to the Countess of Essex. He died on the 4th of August 1633, at the age of seventy-one, and was buried in the old church at Guildford: an altar tomb, with a canopy supported by six black marble pillars, under which is his full-length figure in his robes, marks the spot: at the west end is a curious representation of a sepulchre filled with skulls and bones, and a grating before it carved in the stone. DISSOLUTION OF THE PRIORY, WALSINGHAM AUGUST 4, 1538Give me my scallop-shell of quiet, Let us hope that these beautiful lines of Sir Walter Raleigh were the sincere feelings of many a pious soul, on pilgrimage to the far-famed shrine of our Ladye at Walsingham; a little spot in Norfolk, lying a few miles distant from the sea, which was the rival of our Ladye of Loretto, or St. James of Compostella, in the number of pilgrims who were yearly attracted to it; indeed, the town was created and subsisted solely upon these travellers, being nothing but a collection of inns and hostelries for their accommodation. Walsingham Chapel was founded in 1061, by the widow of Ricoldie de Faverches, and owed its reputation to the fact of its being an exact facsimile of the Santa Casa, or home of the Virgin Mary, at Nazareth; which house was, three hundred years after, said to have been carried by angels to Loretto.My staff of faith to walk upon, My scrip of joy, immortal diet, My bottle of salvation, My gown of glory (hope's true gage), And then I'll take my pilgrimage. The Crusaders and pilgrims to Palestine transferred their affections to the Norfolk shrine, after the Mohammedans had conquered Nazareth; believing that the Virgin had deserted her real home, and established herself in England, when the infidels desecrated the Holy Land. The splendid priory which soon arose beside the chapel was founded by Godfrey de Faverches, and granted to the order of St. Augustine; and in 1420, a large and handsome church was built at the side of the low-roofed shrine of which Erasmus speaks in his famous Colloquy upon Pilgrimages. He says, 'The church is splendid and beautiful, but the Virgin dwells not in it; that veneration and respect is only granted to her Son. She has her church so contrived as to be on the right hand of her Son, but neither in that cloth she live, the building not being finished.' The original shrine he describes as being 'built of wood, pilgrims are admitted through a narrow door at each side. There is but little or no light in it, but what proceeds from wax-tapers yielding a most pleasant and odoriferous smell; but if you look in, you will say it is the seat of the gods, so bright and shining as it is all over with jewels, gold, and silver.' That the treasures of the place, arising from gifts and benefactions, were very great, we have abundant evidence. Lord Burghersh, K.G., left in his will, in 1369, that a statue of himself on horseback should be made in silver, and offered to the Virgin; Henry VII had the same kind of image made, above three feet high, of his own effigy, kneeling on a table, with 'a brode border, and in the same graven and written with large letters, blake enameled, these words: ' Sancte Thoma, intercede pro me.'' The Plantagenet kings were great benefactors to it. Henry III, Edwards I and II, were among those who made the Walsingham pilgrimage. Charles V, when He came secretly, to gain Wolsey's ear, made this pilgrimage his ostensible reason. At no time was it more popular than just before its destruction: Henry VIII walked there barefoot, to present a costly necklace to the Virgin, and made it his favourite place of devotion, with Catharine of Aragon, perhaps partly induced by his minister Wolsey's great affection for the neighbourhood of his birth: yet the caprice, which is perhaps a truer word than principle, of this monarch induced him not long after to order this famous chapel to be desecrated. The dying tyrant is said to have felt this sin lie more heavily on his conscience than many others, and, after all, unable to throw off his early superstitions, he left his soul in charge of the Lady of Walsingham: his poor divorced Catharine did the same with much more sincerity, and ordered two hundred nobles to be given by a pilgrim in charity on his way there. Erasmus gives us a very amusing account of the wonders of the place, and the miracle performed there. 'On the north side there is a gate, which has a very small wicket, so that any one wanting to enter is obliged first to subject his limbs to attack, and then must stoop his head. Our reverend guide related that once a knight, seated on his horse, escaped by this door from the hands of his enemy, who was at the time closely pressing upon him. The wretched man, thinking himself lost, by a sudden aspiration commended his safety to the Virgin who was so near; and, lo!-the unheard of occurrence!-on a sudden the man and horse were together within the precincts of the church, and the pursuer fruitlessly storming without. 'And did he make you swallow such a wonderful story?' 'Unquestionably. He pointed out a brass-plate nailed to the gate, representing the scene; the knight had a beard as long as a goat's, and his dress fitted tightly without a wrinkle.' 'It would be wrong to doubt any longer. 'To the east of this is a chapel full of wonders. A joint of a man's finger is exhibited to us: I kiss it, and then ask: ' Whose relics were these?' He says: 'St Peter's.' Then observing the size of the joint, which might have been that of a giant, I remarked: 'Peter must have been a man of very large size.' At this one of my companions burst into a laugh, which I certainly took ill, and pacified the attendant by offering him a few pence. Before the chapel was a shed, under which are two wells full to the brink; the water is wonderfully cold and efficacious in curing pains in the head. They affirm that the spring suddenly burst from the earth at the command of the most holy Virgin.' (These still exist, and are called the Wishing-wells, as it was believed that the Virgin granted to the pilgrims what they desired when drinking.) 'I asked how many years it might be since that little house was brought thither. He answered: 'Some centuries.' 'But the walls,' I remarked, 'do not bear any signs of age.' He did not dispute the matter. 'But the wooden posts, the roof, and the thatch are new, how, then, do you prove that this was the cottage which was brought from a great distance?' He immediately shewed us a very old bear's skin fixed to the rafters, and almost ridiculed our dulness in not having observed so manifest a proof.' In a more satirical spirit Erasmus goes on to speak of the heavenly milk of the blessed Virgin, which had been brought from the Holy Land through many dangers, making the canon to look aghast at him as if possessed by fury and horrified at his blasphemous inquiries. He next saw the wonderful jewel at the feet of the Virgin, which the French named toad-stone, because it so imitates the figure of a toad as no art could do the like; and what snakes the miracle greater, the stone is very small, the figure does not project, but shines as if enclosed in the jewel itself.'  Among other superstitions belonging to the place, was one that the Milky-way pointed directly to the home of the Virgin, in order to guide pilgrims on their road, hence it was called the Walsingham-Way, which had its counterpart on earth in the broad road which led through Norfolk: at every town that it passed through a cross was erected, pointing out the path to the holy spot; some of these elegant structures still remain. Let us now take a glance at the pilgrims themselves; a class of persons who played no unimportant part in the social life of the middle ages. An example of the corps was clad in a long coat of russet hue, a sort of broad flapped hat, which was as often thrown back as worn on the head, with a long staff in his hand, and silver scallop-shells embroidered on his coat; an armorial bearing, supposed, in the first instance, to have been assumed, because these shells were used as drinking cups and dishes in Palestine. Tin and leaden images were stuck all over his hat and dress, to mark what holy shrines he had visited; this is alluded to in a poem ascribed to Chaucer: Then as manere and custom is, signes there they bought, For men of contre' should knowe whome they had sought, Echo man set his silver in such thing as they liked. And in the meen while the millar had y-picked His bosom full of signys of Caunterbury brochis. They set their signys upon their hedes and some oppon their capp, And sith to the dyner ward they gan for to stapp. The reader will remember the hat of Louis XI of France, described in Quentin Durward as full of these leaden images of the Virgin. In addition to these, the rosary was always hung over the arm, that name being given in consequence of the legend which relates that the Virgin presented her chaplet of beads to St. Dominic, and that it was scented with the sweet perfume of roses. It ought to contain one hundred and fifty beads, in which one Pater-noster comes after every ten Ave-Marias. It was often made of jet or wood, but those of Cordova were exquisitely worked in gold-filigree. A bottle slung at the back, and a pouch in front, completed the orthodox costume. The abuses of these pilgrimages occupy many a page in the old writers; they led to lying, idleness, and mendicancy. A sermon of the year 1407 thus remarks upon them: 'Also I knowe well that when divers men and women will goe thus after their own wines and finding out on pilgrimage, they will ordaine with them before to have with them both men and women that can well sing wanton songs, and some other pilgrimes will have with them bagge-pipes; so that everie town that they come through, what with the noise of their singing and with the sound of their piping, and with the jangling of their Canturburie-bells, and with the barking out of dogges after them, that they make more noice then if the king came there away with all his clarions and many other minstrels. And if these men and women be a moneth out in their pilgrimage, many of them shall be a halfe yeare after great janglers, tale-tellers, and liers.' All which is borne out by mine Host of the Tabarde: Ye gon to Caunterbury; God you spede, The blisful martir quyte you youre mode! And wel I wet, as ye gon by the way Ye sehapen you to talken and to play, For trewely comfort ne mirthe is non, To ryden by the way dumb as a ston: And therefore wold I maken you disport. It will be readily imagined how great was the distress when Henry despoiled this valuable shrine. The people of Norfolk rose in insurrection, as they gained so great a profit from the travellers who passed through the county, and who would now be prevented coming. 'Indeed,' says one, 'it would have made a heart of flint to have melted and wept, to have seen the breaking up of the house, and the sorrowful departure of the monks, every person bent himself to filch and spoil what he could.' The abbey became the property of Thomas Sydney, whose son married the sister of Sir Francis Walsingliam, and died very wealthy. In the Bodleian library there is a poem, entitled a Lament for Walsingham, from which we take a short specimen. Bitter, bitter oh to behoulde, The grasse to growe, Where the walles of Walsingham So stately did shewe Oules doe strike where the sweetest himmes Lately wear songe, Toades and serpents hold their dennes Where the palmers did throng. Weepe, weepe, 0 Walsingham, Whose dayes are nightes, Blessings turned to blasphemies, Holy deedes to despites. Sinne is where our Lady sate, Heaven turned is to helle, Sathan sitte where our Lord did swaye, Walsingham, 0 farewell! But few ruins remain of this once ' holy laude of blessed Walsingham.' A part of the east front of the priory church, with a circular window of flowing tracery, and four windows of the refectory, are standing in the prettily laid-out grounds of the present owner of the estate, the Lee-Warners, by whom it was purchased in 1766. HARROW SHOOTINGS AND HARROW SPEECHESThe 4th of August is associated with a very old custom at Harrow School-now obsolete, and superseded by a celebration of another kind. The practice of archery was coeval with the establishment of this celebrated institution. Indeed, by the rules laid down by John Lyon, the founder of the school, the necessary implements for the proper exercise of this amusement were required to be furnished by the parents of every boy on his entering the school. 'You shall allow your child,' said the ordinances drawn up in 1592, 'at all times bow-shafts, bow-strings, and a bracer.' The Butts at Harrow was, in former days, a beautiful spot a little to the west of the London road, backed by a lofty insulated knoll, crowned with trees, and having rows of grassy seats, cut on the slopes, for spectators. In the early ages of the school, it was customary for the boys to contend for the prize of a silver arrow; the number of competitors being at first six, but afterwards increased to twelve. The competitors were attired in fancy-dresses, white, green, or red satin, decked with spangles; with green silk sashes and caps. In the Harrow Calendar it is stated that one of these dresses is still preserved in the school-library, where it has been for nearly a hundred years. Whoever shot within the three circles which surrounded the bull's-eye, was saluted with a concert of French-horns; and he who first shot twelve times nearest the mark, was proclaimed victor, and marched back in triumph from the Butts to the town, at the head of a procession of boys, carrying and waving the silver arrow. The entertainments of the day were concluded with a ball, given by the winner, in the school-room, to which all the neighbouring families were invited. The late master, the Rev. Dr. Drury, spoke of an old print or drawing of the Butts on the day of celebration, in these terms: 'The village barber is seen walking off, like one of Homer's heroes, with an arrow in his eye, stooping forward, and evidently in great pain, with his hand applied to the wound. It is perfectly true that this Tom of Coventry was so punished; and I have somewhere a ludicrous account of it in Dr. Parr's all but illegible holograph.' Scattered through the early volumes of the Gentleman's Magazine are many notices of the Harrow shootings, with the names of the successful competitors. The gossip of the school comprises a story that, in the last century, three brothers successively carried off three silver arrows, which their father stuck up in three corners of his drawing-room; it became a matter of family pride to fill up the fourth corner; and this was effected by the success of a fourth brother in 1766. Another anecdote was communicated to the Dean of Peter-borough by the Hon. Archibald Macdonald. On one particular 4th of August, two boys, Merry and Love, were equal or nearly so, and both of them decidedly superior to the rest. Love, having shot his last arrow into the bull's eye, was greeted by his school-fellows with a shout, 'Omnia vincit Amor.' 'Not so,' said Merry in an under voice, 'Nos non cedamus Asnori;' and carefully adjusting his shaft, shot it into the bull's eye, a full inch nearer to the centre than his exulting competitor. So he gained the day. The Harrow Shootings were abolished in 1771. Dr. Heath, the head-master at that time, was dissatisfied with the frequent exemptions from the regular business of the school, which those who practised as competitors for the prize claimed as a privilege not to be infringed upon. He also observed, as other masters had done before him, that the contest usually brought down a band of profligate and disorderly persons from the metropolis, to the demoralisation of the village. The Harrovians deeply regretted the ending of their old amusement; and, as a record of it, they still preserve the silver arrow made for 1772, but not used. The annual shootings were succeeded by annual speeches, which, under many modifications, have continued ever since. |