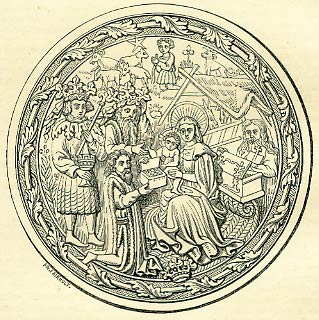

25th December (part 2)The Three MagiIn connection with the birth of the Saviour, and as a pendant to the notice under Twelfth Day, or the Epiphany of the observances commemorative of the visit of the Wise Men of the East to Bethlehem, we shall here introduce some further particulars of the ideas current in medieval times on the subject of these celebrated personages. The legend of the Wise Men of the East, or, as they are styled in the original Greek of St. Matthew's gospel, Μλσι (the Magi), who visited the infant Savor with precious offerings, became, under monkish influence, one of the most popular during the middle ages, and was told with increased and elaborated perspicuity as time advanced. The Scripture nowhere informs us that; these individuals were kings, or their number restricted to three. The legend converts the Magi into kings, gives their names, and a minute account of their stature and the nature of their gifts. Melchior (we are thus told) was king of Nubia, the smallest man of the triad, and he gave the Savior a gift of gold. Balthazar was king of Chaldea, and he offered incense; he was a man of ordinary stature. But the third, Jasper, king of Tarshish, was of high stature, 'a black Ethiope,' and he gave myrrh. All came with 'many rich ornaments belonging to king's array, and also with mules, camels, and horses loaded with great treasure, and with multitude of people, 'to do homage to the Saviour, 'then a little childe of xiii dayes olde.'  The offering of the Magi The barbaric pomp involved in this legend made it a favourite with artists during the middle ages. Our engraving is a copy from a circular plate of silver, chased in high-relief, and partly gilt, which is supposed to have formed the centre of a morse, or large brooch, used to fasten the decorated cope of an ecclesiastic in the latter part of the fourteenth century. The subject has been frequently depicted by the artists subsequent to this period. Van Eyck, Durer, and the German schools were particularly fond of the theme-the latest and most striking work being that by Rubens, who reveled in such pompous displays. The artists of the Low Countries were, probably, also biased by the fact, that the cathedral of Cologne held the shrine in which the bodies of the Magi were said to be deposited, and to which the faithful made many pilgrimages, greatly to the emolument of the city, a result which induced the worthy burghers to distinguish their shield of arms by three crowns only, and to designate the Magi as 'the three kings of Cologne.' It was to the Empress Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, that the religious world was indebted for the discovery of the place of burial of these kings in the far east. She removed their bodies to Constantinople, where they remained in the church of St. Sophia, until the reign of the Emperor Emanuel, who allowed Eustorgius, bishop of Milan, to transfer them to his cathedral. In 1164, when the Emperor Frederick conquered Milan, he gave these treasured relics to Raynuldus, archbishop of Cologne, who removed them to the latter city. His successor, Philip von Heinsberg, placed them in a magnificent reliquary, enriched with gems and enamels, still remaining in its marble shrine in the cathedral, one of the chief wonders of the noble pile, and the principal 'sight' in Cologne. A heavy fee is exacted for opening the doors of the chapel, which is then lighted with lamps, producing a dazzling effect on the mass of gilded and jeweled sculpture, in the centre of which may be seen the three skulls, reputed to be those of the Magi. These relics are enveloped in velvet, and decorated with embroidery and jewels, so that the upper part of each skull only is seen, and the hollow eyes which, as the faithful believe, once rested on the Savior. The popular belief in the great power of intercession and protection possessed by the Magi, as departed saints, was widely spread in the middle ages. Any article that had touched these skulls was believed to have the power of preventing accidents to the bearer while traveling, as well as to counteract sorcery, and guard against sudden death. Their names were also used as a charm, and were inscribed upon girdles, garters, and finger- rings. We engrave two specimens of such rings, both works of the fourteenth century. The upper one is of silver, with the names of the Magi engraved upon it; the lower one is of lead simply cast in a mould, and sold cheap for the use of the commonalty. They were regarded as particularly efficacious in the case of cramp. Traces of this superstition still linger in the curative properties popularly ascribed to certain rings. Bishop Patrick, in his Reflections on the Devotions of the Roman Church, 1674, asks with assumed naivete how these names of the three Wise Men-Melchior, Balthazar, and Jasper-are to be of service, 'when another tradition says they were Apellius, Amerus, and Damascus; a third, that they were Megalath, Galgalath, and Sarasin; and a fourth calls them Ator, Sator, and Peratoras; which last I should choose (in this uncertainty) as having the more kingly sound.' CHRISTMAS CHARITIESWe have already, in commenting on Christmas-day and its observances, remarked on the hallowed feelings of affection and good-will which are generally called forth at the celebration of this anniversary. Quarrels are composed and forgotten, old friendships are renewed and confirmed, and a universal spirit of charity and forgiveness evoked. Nor is this charity merely confined to acts of kindness and generosity among equals; the poor and destitute experience the bounty of their richer neighbors, and are enabled like them to enjoy themselves at the Christmas season. From the Queen downwards, all classes of society contribute their mites to relieve the necessities and increase the comforts of the poor, both as regards food and raiment. Even in the work-houses--those abodes of short-commons and little ease-the authorities, for once in the year, become liberal in their housekeeping, and treat the inmates on Christmas-day to a substantial dinner of roast-beef and plum-pudding. It is quite enlivening to read the account in the daily papers, a morning or two afterwards, of the fare with which the inhabitants of the various work-houses in London and elsewhere were regaled on Christmas-day, a detailed chronicle being furnished both of the quality of the treat and the quantity supplied to each individual. Beggars, too, have a claim on our charity at this season, mange all maxims of political economy, and must not be turned from our doors unrelieved. They may, at least, have their dole of bread and meat; and to whatever bad uses they may possibly turn our bounty, it is not probable that the deed will ever be entered to our discredit in the books of the Recording Angel. Apropos of these sentiments, we introduce the following monitory lines by a well-known author and artist: SCATTER YOUR CRUMBS BY ALFRED CROWQUILL Amidst the freezing sleet and snow, The timid robin comes; In pity drive him not away, But scatter out your crumbs. And leave your door upon the latch For whosoever comes; The poorer they, more welcome give, And scatter out your crumbs. All have to spare, none are too poor, When want with winter comes; The loaf is never all your own, Then scatter out the crumbs. Soon winter falls upon your life, The day of reckoning comes: Against your sins, by high decree, Are weighed those scattered crumbs. In olden times, it was customary to extend the charities of Christmas and the New Year to the lower animals. Burns refers to this practice in 'The Auld Farmer's Address to his Mare,' when presenting her on New-Year's morning with an extra feed of corn: A guid New-year, I wish thee, Maggie! Hae, there's a ripp to thy auld baggie! The great-grandfather of the writer small proprietor in the Carse of Falkirk, in. Scotland, and an Episcopalian-used regularly himself, every Christmas-morning, to carry a special supply of fodder to each individual animal in his stable and cow-house. The old gentleman was wont to say, that this was a morning, of all others in the year, when man and beast ought alike to have occasion to rejoice. CHRISTMAS DECORATIONSThe decking of churches, houses, and shops with evergreens at Christmas, springs from a period far anterior to the revelation of Christianity, and seems proximately to be derived from the custom prevalent during the Saturnalia of the inhabitants of Rome ornamenting their temples and dwellings with green boughs. From this latter circumstance, we find several early ecclesiastical councils prohibiting the members of the church to imitate the pagans in thus ornamenting their houses. But in process of time, the pagan custom was like others of a similar origin, introduced into and incorporated with the ceremonies of the church itself. The sanction of our Saviour likewise came to be pleaded for the practice, he having entered Jerusalem in triumph amid the shouts of the people, who strewed palm-branches in his way. It is evident that the use of flowers and green boughs as a means of decoration, is almost instinctive in human nature; and we accordingly find scarcely any nation, civilized or savage, with which it has not become more or less familiar. The Jews employed it in their Feast of Tabernacles, in the month of September; the ancient Druids and other Celtic nations hung up the mistletoe and green branches of different kinds over their doors, to propitiate the woodland sprites; and a similar usage prevailed, as we have seen, in Rome. In short, the feeling thus so universally exhibited, is one of natural religion, and therefore not to be traced exclusively to any particular creed or form of worship. Stow, that invaluable chronicler, informs us in his Survey of London, that: against the feast of Christmas every man's house, as also their parish churches, were decked with holme [the evergreen oak], ivy, bayes, and whatsoever the season of the year afforded to be green. The conduits and standards in the streets were likewise garnished: among the which I read, that in the year 1444, by tempest of thunder and lightning, towards the morning of Candlemas-day, at the Leadenhall, in Cornhill a standard of tree, being set up in the midst of the pavement, fast in the ground, nailed full of holme and ivie, for disport of Christmass to the people, was tome up and cast downe by the malignant spirit (as was thought), and the stones of the pavement all about were cast in the streets, and into divers houses, so that the people were sore aghast at the great tempest The favorite plants for church decoration at Christmas are holly, bay, rosemary, and laurel. Ivy is rather objectionable, from its associations, having anciently been sacred to Bacchus, and employed largely in the orgies celebrated in honour of the god of wine. Cypress, we are informed, has been sometimes used, but its funereal relations render it rather out of place at a festive season like Christmas. One plant, in special, is excluded -the mystic mistletoe, which, from its antecedents, would be regarded as about as inappropriate to the interior of a church, as the celebration of the old Druidical rites within the sacred building. A solitary exception to this universal exclusion, is mentioned by Dr. Stukeley, who says that it was one time customary to carry a branch of mistletoe, in procession to the high-altar of York Cathedral, and thereafter proclaim a general indulgence and pardon of sins at the gates of the city. 'We cannot help suspecting that this instance recorded by Stukeley, is to be referred to one of the burlesques on the services of the church, which, under the leadership of the Boy-bishop, or the Lord of Misrule, formed so favourite a Christmas-pastime of the populace in bygone times. A quaint old writer thus spiritualists the practice of Christmas decorations. So our churches and 100 houses decked with bayes and rosemary, holly and ivy, and other plants which are always green, winter and summer, signify and put us in mind of His Deity, that the child that now was born was God and man, who should spring up like a tender plant, should always be green and flourishing, and live for evermore. Festive carols, we are informed, used to be chanted at Christmas in praise of the evergreens, so extensively used at that season. The following is a specimen: Holly Here comes holly that is so gent To please all men is his intent. Allelujah! Whosoever against holly do cry, In a rope shall be hung full high. Allelujah! Whosoever against holly do sing, He may weep and his hands wring, Allelujah! Ivy Ivy is soft and meek of speech, Against all bale she is bliss, Well is he that may her reach. Ivy is green, with colours bright, Of all trees best she is, And that I prove will now be right. Ivy beareth berries black, God grant us all his bliss, For there shall be nothing lack. The decorations remain in the churches from Christmas till the end of January, but in accordance with the ecclesiastical canons, they must all be cleared away before the 2nd of February or Candlemas-day. The same holds good as a custom with regard to private dwellings, superstition in both cases rendering it a fatal presage, if any of these sylvan ornaments are retained beyond the period just indicated. Herrick thus alludes to the popular prejudice. Down with the rosemary, and so Down with the bales and mistletoe; Down with the holly, ivie, all Wherewith ye drest the Christmas hall; That so the superstitious find No one least branch there left behind; For look, how many leaves there be Neglected there, maids trust to me, So many goblins you shall see. Aubrey informs us that in several parts of Oxford-shire, it was the custom for the maid-servant to ask the man for ivy to decorate the house; and if he refused or neglected to fetch in a supply, the maids stole a pair of his breeches, and nailed them up to the gate in the yard or highway. A similar usage prevailed in other places, when the refusal to comply with such a request incurred the penalty of being debarred from the well-known privileges of the mistletoe. OLD ENGLISH CHRISTMAS FARE

The 'brave days of old' were, if rude and unrefined, at least distinguished by a hearty and profuse hospitality. During the Christmas holidays, open-house was kept by the barons and knights, and for a fortnight and upwards, nothing was heard of but revelry and feasting. The grand feast, however, given by the feudal chieftain to his friends and retainers, took place with great pomp and circumstance on Christmas-day. Among the dishes served up on this important occasion, the boar's head was first at the feast and foremost on the board. Heralded by a jubilant flourish of trumpets, and accompanied by strains of merry minstrelsy, it was carried-on a dish of gold or silver, no meaner metal would suffice-into the banqueting-hall by the sewer; who, as he advanced at the head of the stately procession of nobles, knights, and ladies, sang: Caput apri defero, Reddens Laudes Domino. The boar's head in hand bring I With garlands gay and rosemary; I pray you all sing merrily, Quid estis in convivio. The boar's head, I understand, Is the chief service in this land; Look wherever it be found, Service cum cantico. Be glad, both more and less, For this hath ordained our steward. To cheer you all this Christmas The boar's head and mustard! Caput apri defero, Reddens laudes Domino. The brawner's head was then placed upon the table with a solemn gravity befitting the dignity of such a noble dish: Sweet rosemary and bays around it spread; His foaming tusks with some large pippin graced, Or midst those thundering spears an orange placed, Sauce, like himself, offensive to its foes, The roguish mustard, dangerous to the nose. The latter condiment was indispensable. An old book of instruction for the proper service of the royal table says emphatically: First set forth mustard with brawn; take your knife in your hand, and cut brawn in the dish as it lieth, and lay on your sovereign's trencher, and see there be mustard. When Christmas, in the time of the Commonwealth, was threatened with extinction by act of parliament, the tallow-chandlers loudly complained that they could find no sale for their mustard, because of the diminished consumption of brawn in the land. Parliament failed to put down Christmas, but the boar's-head never recovered its old supremacy at the table. Still, its memory was cherished in some nooks and corners of Old England long after it had ceased to rule the roast. The lessee of the tithes of Horn Church, Essex, had, every Christmas, to provide a boar's-head, which, after being dressed and garnished with bay, was wrestled for in a field adjoining the church. The custom of serving up the ancient dish at Queen's College, Oxford, to a variation of the old carol, sprung, according to the university legend, from a valorous act on the part of a student of the college in question. While walking in Shot over forest, studying his Aristotle, he was suddenly made aware of the presence of a wild-boar, by the animal rushing at him open-mouthed. With great presence of mind, and the exclamation, 'Greacum est,' the collegian thrust the philosopher's ethics down his assailant's throat, and having choked the savage with the sage, went on his way rejoicing. The Lord Jersey of the Walpolian era was a great lover of the quondam Christmas favourite, and also-according to her own account-of Miss Ford, the lady whom Whitehead and Lord Holdernesse thought so admirably adapted for Gray's friend, Mason, 'being excellent in singing, loving solitude, and full of immeasurable affectations. 'Lord Jersey sent Miss Ford a boar's head, a strange first present, at which the lady laughed, saying she 'had often had the honour of meeting it at his lordship's table, and would have ate it had it been eatable! 'Her noble admirer resented the scornful insinuation, and indignantly replied, that the head in question was not the one the lady had seen so often, but one perfectly fresh and sweet, having been taken out of the pickle that very morning; and not content with defending his head, Lord Jersey revenged himself by denying that his heart had ever been susceptible of the charms of the fair epicure. Next in importance to the boar's-head as a Christmas-dish came the peacock. To prepare Argus for the table was a task entailing no little trouble. The skin was first carefully stripped off, with the plumage adhering; the bird was then roasted; when done and partially cooled, it was sewed up again in its feathers, its beak gilt, and so sent to table. Sometimes the whole body was covered with leaf-gold, and a piece of cotton, saturated with spirits, placed in its beak, and lighted before the carver commenced operations. This 'food for lovers and meat for lords' was stuffed with spices and sweet herbs, basted with yolk of egg, and served with plenty of gravy; on great occasions, as many as three fat wethers being bruised to make enough for a single peacock. The noble bird was not served by common hands; that privilege was reserved for the lady-guests most distinguished by birth or beauty. One of them carried it into the dining-hall to the sound of music, the rest of the ladies following in due order. The bearer of the dish set it down before the master of the house or his most honoured guest. After a tournament, the victor in the lists was expected to shew his skill in cutting up inferior animals. On such occasions, however, the bird was usually served in a pie, at one end of which his plumed crest appeared above the crust, while at the other his tail was unfolded in all its glory. Over this splendid dish did the knights-errant swear to undertake any perilous enterprise that came in their way, and succour lovely woman in distress after the most approved chevalier fashion. Hence Justice Shallow derived his oath of 'By cock and pie!' The latest instance of peacock-eating we can call to mind, is that of a dinner given to William IV. when Duke of Clarence, by the governor of Grenada; when his royal highness was astonished by the appearance of the many-hued bird, dressed in a manner that would have delighted a medieval de or Sober. Geese, capons, pheasants drenched with amber-grease, and pies of carps-tongues, helped to furnish the table in bygone Christmases, but there was one national dish-neither flesh, fowl, nor good red herring-which was held indispensable. This was furmante, frumenty or furmety, concocted-according to the most ancient formula extant-in this wise: 'Take clean wheat, and bray it in a mortar, that the hulls be all gone off, and seethe it till it burst, and take it up and let it cool; and take clean fresh broth, and sweet milk of almonds, or sweet milk of kine, and temper it all; and take the yolks of eggs. Boil it a little, and set it down and mess it forth with fat venison or fresh mutton. 'Venison was seldom served without this accompaniment, but furmety, sweetened with sugar, was a favorite dish of itself, the 'clean broth' being omitted when a lord was to be the partaker. Mince-pies were popular under the name of 'mutton-pies,' so early as 1596, later authorities all agreeing in substituting neats-tongue in the place of mutton, the remaining ingredients being much the same as those recommended in modern recipes. They were also known as shred and Christmas pies: Without the door let sorrow lie, And if for cold it hap to die, We'll bury it in a Christmas-pie, And evermore be merry! In Herrick's time it was customary to set a watch upon the pies, on the night before Christmas, lest sweet-toothed thieves should lay felonious fingers on them; the jovial vicar sings: Come guard the Christmas-pie, That the thief, though ne'er so sly, With his flesh-hooks don't come nigh, To catch it, From him, who all alone sits there, Having his eyes still in his ear, And a deal of nightly fear, To watch it. Selden tells us mince-pies were baked in a coffin-shaped crust, intended to represent the cratch or manger in which the Holy Child was laid; but we are inclined to doubt his statement, as we find our old English cookery-books always style the crust of a pie 'the coffin.' When a lady asked Dr. Parr on what day it was proper to commence eating mince-pies, he answered, 'Begin on O. Sapientia (December 16th), but please to say Christmas-pie, not mince-pie; mince-pie is puritanical. 'The doctor was wrong at least on the last of these points, if not on both. The Christmas festival, it is maintained by many, does not commence before Christmas Eve, and the mince-pie was known before the days of Praise-God Barebones and his strait-laced brethren, for Ben Jonson personifies it under that name in his Masque of Christmas. Likely enough, the name of 'Christmas-pie' was obnoxious to puritanical ears, as the enjoying of the dainty itself at that particular season was offensive to puritan taste: All plums the prophet's sons deny, And spice-broths are too hot; Treason's in a December-pie, And death within the pot. Or, as another rhymster has it: The high-shoe lords of Cromwell's making Were not for dainties-roasting, baking; The chief est food they found most good in, Was rusty bacon and bag-pudding; Plum-broth was popish, and mince-pie- O that was flat idolatry! In after-times, the Quakers took up the prejudice, and some church-going folks even thought it was not meet for clergymen to enjoy the delicacy, a notion which called forth the following remonstrance from Bickerstaffe.-'The Christmas-pie is, in its own nature, a kind of consecrated cake, and a badge of distinction; and yet it is often forbidden, the Druid of the family. Strange that a sirloin of beef, whether boiled or roasted, when entire is exposed to the utmost depredations and invasions; but if minced into small pieces, and tossed up with plumbs and sugar, it changes its property, and forsooth is meat for his master.' Mortifying as Lord Macartney's great plum-pudding failure may have been to the diplomatist, he might have consoled himself by remembering that plum-porridge was the progenitor of the pride and glory of an English Christmas. In old times, plum-pottage was always served with the first course of a Christmas-dinner. It was made by boiling beef or mutton with broth, thickened with brown bread; when half-boiled, raisins, currants, prunes, cloves, mace and ginger were added, and when the mess had been thoroughly boiled, it was sent to table with the best meats. Sir. Roger de Coverley thought there was some hope of a dissenter, when he saw him enjoy his porridge at the hall on Christmas-day. Plum-broth figures in Poor Robin's Almanac for 1750, among the items of Christmas fare, and Mrs. Frazer, 'sole teacher of the art of cookery in Edinburgh, and several years 'colleague, and afterwards successor to Mrs. M'Iver,' who published a cookery-book in 1791, thought it necessary to include plum-pottage among her soups. Brand partook of a tureenful of 'luscious plum-porridge' at the table of the royal chaplain in 1801, but that is the latest appearance of this once indispensable dish of which we have any record. As to plum-pudding, we are thoroughly at fault. Rabisha gives a recipe in his Whole Body of Cookery Dissected (1675), for a pudding to be boiled in a basin, which bears a great resemblance to our modern Christmas favorite, but does not include it in his bills of fare for winter, although 'a dish of stewed broth, if at Christmas,' figures therein. It shared honours with the porridge in Addison's time, however, for the Tatter tells us: 'No man of the most rigid virtue gives offence by an excess in plum-pudding or plum-porridge, because they are the first parts of the dinner;' but the Mrs. Frazer above mentioned is the earliest culinary authority we find describing its concoction, at least under the name of 'plumb-pudding.' While Christmas, as far as eating was concerned, always had its specialities, its liquor carte was unlimited. A carolist of the thirteenth century sings (we follow Douce's literal translation): Lordlings, Christmas loves good drinking, Wines of Gascoigne, France, Anjou, English ale that drives out thinking, Prince of liquors, old or new. Every neighbour shares the bowl, Drinks of the spicy liquor deep; Drinks his fill without control, Till he drowns his care in sleep. And to attain that end every exhilarating liquor was pressed into service by our ancestors. |