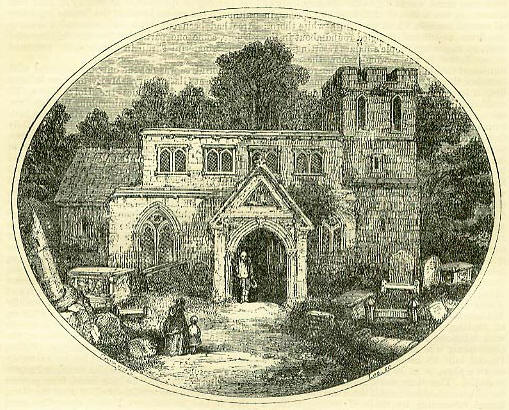

25th December (part 3)THE CHRISTIAN AND OTHER ERAS IN CHRONOLOGYThe Christian Era adopts a particular year as a commencement or starting-point, from which any subsequent year may be reckoned. It has no particular connection with Christmas-day, but it may suitably be noticed in this place as associated with that great festival. All nations who have made any great advance in civilization, have found it useful to adopt some particular year as a chronological basis. The Romans adopted for this purpose the year, and even the day, which some of their historians assigned as the date for the foundation of Rome. That particular date, designated according to our present chronology, was the 21st of April, in the year 754 B.C. They were wont to express it by the letters A.U.C., or Ab urbe condita, signifying 'from the foundation of the city.' The change effected in the calendar by the first two Caesars, and which, with the alteration afterwards rendered necessary by the lapse of centuries, forms, to the present day, the standard for computing the length and divisions of the year, took place 47 B.C. or 707 A.U.C. The Olympiads were a Greek mode of computing time, depending on chronological groups, each of which measured respectively four years in length. They began in 776 B.C., in commemoration of an event connected with the Olympic Games. Each period of four years was called an Olympiad; and any particular date was denoted by the number of the Olympiad, and the number of the year in it; such as the third year of the first Olympiad, the first year of the fourth Olympiad, and so on. The Greeks, like the Romans, made in ancient times their civil years a little longer or a little shorter than the true year, and were, like them, forced to reform their calendar occasionally. One of these reforms was made by Meton in 432 B.C., a year which corresponded to the fourth year of the eighty-sixth Olympiad; and another in 330 B.C. When the power of Greece sank to a shadow under the mighty influence of that of Rome, the mode of reckoning by Olympiads gradually went out of use. The Christian Era, which is now adopted by all Christian countries, dates from the year in which Christ was born. According to Greek chronology, that year was the fourth of the 194th Olympiad; according to Roman, it was the year 753 A.U.C.-or 754, if the different dates for beginning the year be rectified. It is remarkable, however, that the Christian era was not introduced as a basis of reckoning till the sixth century; and even then its adoption made very slow progress. There is an ambiguity connected with the Christian era, which must be borne in mind in comparing ancient elates. Some chronologists reckon the year immediately before the birth of Christ, as 1 B.C.; while others call it O.B.C., reserving 1 B.C. for the actual year of the birth. There is much to be adduced in favour of each of these plans; but it suffices to say that the former is the one most usually adopted. The Julian Period is a measure of time proposed by Joseph Scalier, consisting of the very long period of 7980 years. It is not, properly speaking, a chronological era; but it is much used by chronologists on account of its affording considerable facilities for comparing different eras with each other, and in marking, without ambiguity, the years before Christ. The number of years (7980) forming the Julian period, marks the interval after which the sun, moon, and earth will come round to exactly the same positions as at the commencement of the cycle. The exact explanation is too technical to be given here; but we may mention the following two rules:-To convert any date B.C. into the Julian system, subtract the year B.C. from 4714, and the remainder is the corresponding year in the Julian period; to convert any date A.D. into the Julian system, add 4713 to the year of the Christian era. The Mohammedan Era, used by most or all Mohammedan nations, dates from the flight of Mohammed to Medina-the 15th of July, 622 A.D. This date is known as the Hegira, or flight. As the Christian era is supposed to begin on the 1st of January, year 0, a process of addition will easily transfer a particular date from the Mohammedan to the Christian era. For some purposes, it is useful to be able to transfer a particular year from the Roman to the Christian era. The rule for doing so is this: If the given Roman year be less than 754, deduct it from 754; if the given Roman year be not less than 754, deduct 753 from it; the remainder gives the year B.C. in the one case, and A. D. in the other. In like manner it may be useful to know how to convert years of the Greek Olympiads to years of the Christian era. It is done thus: Multiply the next preceding Olympiad by 4, and add the odd years; subtract the sum from 777 if before Christ, or subtract 776 from the sum if after Christ; and the remainder will be the commencement of the given year-generally about the middle of July in the Christian year. In regard to all these five eras (and many others of less importance), there is difficulty and confusion in having to count sometimes backwards and some-times forward, according as a particular date is before or after the commencement of the era. To get over this complexity, the Creation of the World has been adopted, by Christians and Jews alike, as the commencement of a universal era. This would be unexceptionable, if authorities agreed as to the number of years which elapsed between that event and the birth of Christ; but so far are they from agreeing, that, according to competent authorities, there are one hundred and forty different computations of this interval! The one most usually adopted by English writers is 4004 years; but they vary from 3616 up to 6484 years. The symbol A.M., or Anno Mundi, signifying 'year of the world,' is arrived at by adding 4004 to the Christian designation for the year-that is, if the popular English chronology be adopted. There are, however, three other calculations for the year of the world that have acquired some historical note; and the best almanacs now give the following among other adjustments of eras-taking the year 1863 as an example. SIR ISAAC NEWTON AND THE APPLEThe Christmas-day of 1642 was marked by the birth of one of the world's greatest men-one who effected more than any other person in rendering the world familiar to us, in an astronomical point of view. During his long and invaluable life, which extended to the 20th of March 1727 (he presided at the meeting of the Royal Society so late as the 28th of February in that year, when more than eighty-four years of age), his researches extended over an illimitable domain of science, and are imperishably written on the page of philosophy. One or two incidents connected with his life will be found narrated in a previous article; but we may suitably notice, in this place, the remarkable way in which the grandest and most sublime of all his discoveries has become popularly associated with a very trivial circumstance-the fall of an apple. It is curious to trace the manner in which this apple-story has been told by different writers, and the different opinions formed concerning it. Pemberton, who received from Newton himself the history of his first ideas of gravitation, does not mention the apple, but speaks simply of the idea having occurred to the philosopher 'as he sat alone in a garden.' Voltaire says: One day, in the year 1666, Newton went into the country, and seeing fruit fall from a tree (as his niece, Madame Conduit, has informed me), entered into a profound train of thought as to the causes which could lead to sucha drawing-together or attraction.' Martin Folkes speaks of the fruit being an apple. Hegel, referring to this subject, alludes contemptuously to the story of the apple, as a modern version of the history of the tree of knowledge, with whose fruit the serpent beguiled Eve. Gauss, 'a great mathematician, who believes that a philosopher worthy of the name would not need to have his attention drawn to the subject by so trivial an incident, says: 'The history of the apple is too absurd. Whether the apple fell or not, how can any one believe that such a discovery could in that way be accelerated or retarded? Undoubtedly, the occurrence was something of this sort. There comes to Newton a stupid importunate man, who asks him how he hit upon his great discovery. When Newton had convinced himself what a noodle he had to do with, and wanted to get rid of the man, he told him that an apple fell on his nose; and this made the matter quite clear to the man, and he went away satisfied.' Sir. David Brewster, in his Life of Newton, does not expressly declare either his acceptance or rejection of the apple-legend; but his tone denotes the former rather than the latter. He considers the date to have been more probably 1665 than 1666, when: the apple is said to have fallen from the tree at Woolsthorpe, and suggested to Newton the idea of gravity. When sitting alone in the garden, and speculating on the power of gravity, it occurred to him that as the same power by which the apple fell to the ground was not sensibly diminished at the greatest distance from the centre of the earth to which we can reach, neither at the summits of the loftiest spires, nor on the tops of the highest mountains, it might extend to the moon and retain her in her orbit, in the same manner as it bends into a curve a stone or a cannon ball, when projected in a straight line from the surface of the earth. If the moon was thus kept in her orbit by gravitation to the earth, or, in other words, its attraction, it was equally probable, he thought, that the planets were kept in their orbits by gravitating towards the sun. Kepler had discovered the great law of the planetary motions, that the squares of their periodic times were as the cubes of their distances from the sun; and hence Newton drew the important conclusion, that the force of gravity or attraction, by which the planets were retained in their orbits, varies as the square of their distances from the sun. Knowing the force of gravity at the earth's surface, he was, therefore, led to compare it with the force exhibited in the actual motion of the moon, in a circular orbit; but having assumed that the distance of the moon from the earth was equal to sixty of the earth's semi-diameters, he found that the force by which the moon was drawn from its rectilineal path in a second of time was only 13.9 feet, whereas, at the surface of the earth it was 16.1 feet. This great discrepancy between his theory and what he then considered to be the fact, induced him to abandon the subject, and pursue other subjects with which he had been previously occupied. In a note, Sir. David adverts to the fact that both Newton's niece and Martin Folkes (who was at that time president of the Royal Society) had mentioned the story of the apple; but that neither Whiston nor Pemberton had done so. He speaks of a proceeding of his own, which denotes an affection towards Newton's tree at Woolsthorpe, such as might be felt by one who believed the story: We saw the apple-tree in 1814, and brought away a portion of one of its roots. The tree was so much decayed that it was taken down in 1820, and the wood of it carefully preserved by Mr. Turner of Stoke Rocheford. Professor De Morgan, in a discussion which arose on this subject a few years ago in the pages of Notes and Queries, points out somewhat satirically, that the fact of such a tree having stood in Newton's garden, goes very little way towards proving that the fall of an apple from that tree suggested the mighty theory to the philosopher; and he illustrates it by the story of a man who once said: Sir, he made a chimney in my father's house, and the bricks are alive to this day to testify it; therefore deny it not. Mr. De Morgan believes that the current story grew out of a conversation, magnified in the way of which we have such a multitude of instances. Sir. Isaac, in casual talk with his niece, may have mentioned the fall of some fruit as having once struck his mind, when he was pondering on the moon's motion; and she, without any intention of deceiving, may have retailed this conversation in a way calculated to give too much importance to it. The story of the apple is pleasant enough, and would need no serious discussion, if it were not connected with a remarkable misapprehension. As told, the myth is made to convey the idea that the fall of an apple put into Newton's mind what had never entered into the mind of any one before him-namely, the same kind of attraction between several bodies as exists between an apple and the earth. In this way, the real glory of such men as Newton is lowered. It should be known that the idea had been for many years floating before the minds of physical inquirers, in order that a proper estimate may be formed of the way in which Newton's power cleared away the confusion, and vanquished the difficulties which had prevented very able men from proceeding beyond conjecture. Mr. De Morgan proceeds to shew that Kepler, Bouillard, and Huyghens, had all made discoveries, or put forth speculations, relating to the probable law by which the heavenly bodies attract each other; and that Newton, comparing those partial results, and bringing his own idea of universal gravitation to bear upon them, arrived at his important conclusions, without needing any such aid as the fall of an apple. It may be mentioned as a curious circumstance, that a controversy arose, a few years ago, on the question whether or not Cicero anticipated Newton in the discovery or announcement of the great theory of gravitation. The matter is worthy of note, because it illustrates the imperfect way in which that theory is often understood. In the Tusculan Disputations of Cicero, this passage occurs: 'Qud omnia delata gravitate medium mundi locum semper expetant.' The meaning of the passage has been regarded as somewhat obscure; and in some editions In qud occurs instead of Qua; nevertheless the idea is that of a central point, towards which all things gravitate. In all probability, others preceded Cicero in enunciating this theory. But Newton's great achievement was to dismiss this idea of a fixed point altogether, and to substitute the theory of universal for that of central gravitation; that is, that every particle gravitates towards every other. If this principle be admitted, together with the law that the force of the attraction varies inversely as the square of the distance, then the whole of the sublime system of astronomy, so far as concerns the movements of the heavenly bodies, becomes harmonious and intelligible. Assuredly Cicero never conceived the Newtonian idea, that when a ball falls to meet the earth, the earth rises a little way to meet the ball-which is one consequence of the law, that the ball attracts the earth, as well as being attracted by it. We may expect, in spite of all the arguments of the sages, that the story of the apple will continue in favour. In the beautiful new museum at Oxford, the statue of Newton is sculptured with the renowned pippin at the philosopher's feet. LEGEND OF THE GLASTONBURY THORNThe miraculous thorn-tree of Glastonbury Abbey, in Somersetshure, was stoutly believed in until very recent times. One of the first accounts of it in print was given in Hearse's History and Antiquities of Glastonbury, published in 1722; the narration consists of a short paper by Mr. Euston, called 'A little Monument to the once famous Abbey and Borough of Glastonbury, .. . with an Account of the Miraculous Thorn, that blows still on Christmas-day, and the wonderful Walnut-tree, that annually used to blow upon St. Barnaby's Day.' 'My curiosity,' he says, 'having led me twice to Glastonbury within these two years, and inquiring there into the antiquity, history, and rarities of the place, I was told by the innkeeper where I set up my horses, who rents a considerable part of the enclosure of the late dissolved abbey, that St. Joseph of Arimathea landed not far from the town, at a place where there was an oak planted in memory of his landing, called the Oak of Avalon; that he (Joseph) and his companions marched thence to a hill near a mile on the south side of the town, and there being weary, rested themselves; which gave the hill the name of Weary-all-Hill; that St. Joseph stuck on the hill his staff, being a dry hawthorn-stick, which grew, and constantly budded and Mowed upon Christmas-day; but, in the time of the Civil Wars, that thorn was grubbed up. However, there were, in the town and neighborhood, several trees raised from that thorn, which yearly budded and blowed upon Christmas-day, as the old root did. Eyston states that he was induced, by this narration, to search for printed notices of this famous thorn; and he came to a conclusion, that whether it sprang from St. Joseph of Arimathea's dry staff, stuck by him in the ground when he rested there, I cannot find, but beyond all dispute it sprang up miraculously! 'This tree, growing on the south ridge of Weary-all-Hill (locally abbreviated into Werrall), had a double trunk in the time of Queen Elizabeth; 'in whose days a saint-like Puritan, taking offence at it, hewed down the biggest of the two trunks, and had cut down the other body in all likelihood, had he not been miraculously punished by cutting his leg, and one of the chips flying up to his head, which put out one of his eyes. Though the trunk cut off was separated quite from the root, excepting a little of the hark which stuck to the rest of the body, and lay above the ground above thirty years together, yet it still continued to flourish as the other part of it did which was left standing; and after this again, when it was quite taken away, and cast into a ditch, it flourished and budded as it used to do before. A year after this, it was stolen away, not known by whom or whither. We are then, on the authority of a Mr. Broughton, told how the remaining trunk appeared, after its companion had been lopped off and secretly carried away. The remaining trunk was as big as the ordinary body of a man. It was a tree of that kind and species, in all natural respects, which we term a white thorn; but it was so cut and mangled round about in the bark, by engraving people 's names resorting hither to see it, that it was a wonder how the sap and nutriment should be diffused from the root to the branches thereof, which were also so maimed and broken by comers thither, that I wonder how it could continue any vegetation, or grow at all; yet the arms and boughs were spread and dilated in a circular manner as far or further than any other trees freed from such impediments of like proportion, bearing haws as fully and plentifully as others do. The blossoms of this tree were such curiosities beyond seas, that the Bristol merchants carried them into foreign parts. 'But this second trunk-which bore the usual infliction of the names of silly visitors-was in its turn doomed to destruction. This trunk was likewise cut down by a military saint, as Mr. Andrew Paschal calls him, in the rebellion which happened in King Charles I's time. However, there are at present divers trees from it, by grafting and inoculation, preserved in the town and country adjacent; amongst other places, there is one in the garden of a currier, living in the principal street; a second at the White Hart Inn; and a third in the garden of William Strode, Esquire. Then ensues a specimen of trading, by no means rare in connection with religious relics: There is a person about Glastonbury who has a nursery of them, who, Mr. Paschal tells us he is informed, sells them for a crown a piece, or as he can get. Nothing is more probable. That there was a thorn-tree growing on the hill, is undoubted; and if there was any religious legend concerning its mode of getting there, a strong motive would be afforded for preparing for sale young plants, after the old one had disappeared. Down to very recent times, thorn-trees have been shewn in various parts of Somersetshire, each claiming to be the Glastonbury thorn. In Withering's Arrangement of British Plants, the tree is described botanically, and then (in the edition of 1818) the author says: 'It does not grow within the abbey at Glastonbury, but in a lane beyond the churchyard, on the other side of the street, by the side of a pit. It appears to be a very old tree: an old woman of ninety (about thirty years ago) never remembers it otherwise than it now appears. There is another tree of the same kind, two or three miles from Glastonbury. It has been reported to have no thorns; but that I found to be a mistake. It has thorns, like other hawthorns, but which also in large trees are but few. It blossoms twice a year. The winter blossoms, which are about the size of a sixpence, appear about Christmas, and sooner if the winter be severe.' Concerning the alleged flowering of the tree on Christmas-day especially, there is a curious entry in the Gentleman's Magazine for January 1753, when the public were under some embarrassment as to dates, owing to the change from the old style to the new. 'Glastonbury.-A vast concourse of people attended the noted thorn on Christmas-day, new style; but, to their great disappointment, there was no appearance of its blowing, which made them watch it narrowly the 5th of January, the Christmas-day, old style, when it blowed as usual.' Whether or not we credit the fact, that the tree did blossom precisely on the day in question, it is worthy of note that although the second trunk of the famous legendary tree had been cut down and removed a century before, some one particular tree was still regarded as the wonderful shrub in question, the perennial miracle. A thorn-tree was not the only one regarded with reverence at Glastonbury. Mr. Eyston thus informs us of another: Besides the Holy Thorn, Mr. Camden says there was a miraculous Walnut-Tree, which, by the marginal notes that Mr. Gibson hath set upon Camden, I found grew in the Holy Churchyard, near St. Joseph's Chappel. This tree, they say, never budded forth before the Feast of St. Barnabas, which is on the eleventh of June, and on that very day shot out leaves and flourish 't then as much as others of that kind. Mr. Broughton says the stock was remaining still alive in his time, with a few small branches, which continued yearly to bring forth leaves upon St. Barnabas 's Day as usual. The branches, when he saw it, being too email, young, and tender to bring forth fruit, or sustain their weight; but now this tree is likewise gone, yet there is a young tree planted in its place, but whether it blows, as the old one did, or, indeed, whether it was raised from the old one, I cannot tell. Doctor James Montague, Bishop of Bath and Wells in King James I's days, was so wonderfully taken with the extraordinariness of the Holy Thorn, and this Walnut-Tree, that he thought a branch of these trees was worthy the acceptance of the then Queen Anne, King James I's consort. Fuller, indeed, ridicules the Holy Thorn; but he is severely reproved for it by Doctor Heylin (another Protestant writer), who says 'he hath heard from persons of great worth and credit, dwelling near the place, that it had budded and blowed upon Christmas Day,' as we have above asserted. A flat stone, with certain initials cut in it, at the present day marks the spot where the famous tree once stood, and where, according to the legend, Joseph of Arimathea stuck his pilgrim's staff into the ground. CHRISTMAS CUSTOM AT CUMNORThere is a pleasant Christmas custom connected with the parish of Cumnor, in Berkshire, the church of which is a vicarage, and a beautiful specimen of the venerable parochial edifices of that kind in England. On Christmas-day, after evening-service, the parishioners, who are liable to pay any tithes, repair to the vicarage, and are there entertained with bread, cheese, and ale. It is no benefaction on the part of the vicar, but claimed as a right on the part of the parishioners, and even the quantity of the good things which the vicar brings forward is specified. He must have four bushels of malt brewed in ale and small-beer, two bushels of wheat made into bread, and half a hundredweight of cheese; and whatever remains unconsumed by the vicarage-payers is distributed next day, after morning prayers, among the poor.  In connection with this parish, there is another curious custom, arising from the fact that Cassenton, a little district on the opposite side of the Thames, was once a part of it. The Cassenton people had a space on the north side of the church set apart fortheir burials, and on this account paid sixpence a year to Cumnor. They had to bring their dead across the Thames at Somerford Mead, where the plank stones they used in crossing remained long after visible; thence they came along a 'riding' in Cumnor Wood, which they claimed as their church-way, beginning the psalm-singing at a particular spot, which marked the latter part of, the ceremonial. Not less curious is the perambulation performed in this parish during Rogation week. On arriving at Swinford Ferry, the procession goes across and lays hold of the twigs on the opposite shore, to mark that they claim the breadth of the river as within the bounds of the parish. The ferryman then delivers to the vicar a noble (6s. 8d.), in a bowl of the river-water, along with a clean napkin. The vicar fishes out the money, wipes his fingers, and distributes the water among the people in commemoration of the custom. It seems a practice such as the Total Abstinence Society would approve of; but we are bound to narrate that the vicarage-dues collected on the occasion, are for the most part diffused, in the form of ale, among the thirsty parishioners. THE SEVERE CHRISTMAS OF 1860: INTENSE COLD AND ITS EFFECTSThe Christmas of 1860 is believed to have been the severest ever experienced in Britain. At nine o'clock in the morning of Christmas-day in that year, the thermometer, at the Royal Humane Society's Receiving House, in Hyde Park, London, marked 15° Fahrenheit, or 17° below the freezing-point, but this was a mild temperature compared with what was prevalent in many parts of the country during the preceding night. Mr. E. J. Lowe, a celebrated meteorologist, writing on 25th December to the Times, from his observatory at Beeston, near Nottingham, says: This morning the temperature at four feet above the ground was 8° below zero, and on the grass 13.8° below zero, or 45.8° of frost. The maximum heat yesterday was only 2°, and from 7 P.M. till 11 A.M. the temperature never rose as high as zero of Fahrenheit's thermometer. At the present time (12.30 P.M.), the temperature is 7°above zero at four feet, and 2.5° above zero on the grass. Other observations recorded throughout England correspond with this account of the intensity of the cold, by which, at a nearly uniform rate, the three days from the 24th to the 26th December were characterized. The severity of that time must still be fresh in the memory of our readers. In the letter of Mr. Lowe, above quoted, he speaks of having: just seen a horse pass with icicles at his nose three inches in length, and as thick as three fingers. Those who then wore mustaches must remember how that appendage to the upper-lip became, through the congelation of the vapour of the breath, almost instantaneously stiff and matted together, as soon as the wearer put his head out of doors. What made this severity of cold the more remarkable, was the circumstance that for many years previously the inhabitants of the British Islands had experienced a succession of generally mild winters, and the present generation had almost come to regard as legendary the accounts which their fathers related to them of the hard frosts and terrible winters of former times. Here, therefore, was an instance of a reduction of temperature unparalleled, not only in the recollection of the oldest person living, but likewise in any trustworthy record of the past. During the three days referred to, the damage inflicted on vegetation of all kinds was enormous. The following account of the effects of the frost in a single garden, in a well-wooded part of the county of Suffolk, may serve as a specimen of the general damage occasioned throughout England. The garden referred to is bounded on the west by a box-hedge, and on the south by a low wall, within which was a strip of shrubbery consisting of laurels, Portugal laurels, laurustinus, red cedar, arbor vitae, phillyrea, &c. Besides these, there stood in the garden some evergreen oaks, five healthy trees of some forty years 'growth, two yews (which were of unknown age, but had been large trees beyond the memory of man), and a few younger ones between thirty and forty years old. All these, with the exception of the young yew-trees, the red cedars, the box, some of the arbor vitae and some little evergreen oaks, were either killed outright, or else so injured that it became necessary to cut them down. Nor was this done hastily without waiting to see whether they would recover themselves; ample time was given for discovering whether it was only a temporary check from which the trees and shrubs were suffering, or whether it was an utter destruction of that part of them which was above ground. In some cases, it was found that the root was still alive, and this afterwards sent forth fresh shoots, but in other cases it turned out to be a destruction literally 'root and branch.' Some of the trees, indeed, after having been cut down level with the ground, made a desperate attempt to revive, and sent up apparently healthy shoots; but the attempt was unsuccessful, and the shoots withered. Nor was the damage confined to the evergreens: fruit-trees suffered also; for instance, apple-trees put forth leaves and flowers, which looked well enough for a time, but, before the summer was over, these withered, as if they had been burned; while one large walnut-tree, half a century old, not only had its young last year's shoots killed, but lost some of its largest branches. Beyond the limits of the garden referred to, the effects of this frost were no less remarkable. Elm-trees were great sufferers; they, along with the very oaks, had many of their outer twigs killed; and a magnificent, perhaps unique, avenue of cedars of Lebanon, which must have been among the oldest of their kind in the kingdom (they were only introduced in Charles II's reign) was almost entirely ruined. Notwithstanding this unexampled descent of temperature, the nadir, as it may be termed, of cold yet experienced in Britain, the period during which it continued to prevail was of such short duration that there was no time for it to effect those wonderful results which we read of in former times as occasioned by a severe and unusually protracted frost. In a former part of this work, we have given an account of several remarkably hard frosts, which are recorded to have taken place in England. From a periodical work we extract the following notice of similar instances which occurred chiefly on the continent of Europe in past ages. In the year 401, the Black Sea was entirely frozen over. In 452, the Danube was frozen, so that Thredmare marched on the ice to Swabia, to avenge his brother 's death. In 642, the cold was so intense that the Strait of Dardanelles and the Black Sea were entirely frozen over. The snow, in some places, drifted to the depth of 90 feet, and the ice was heaped in such quantities on the cities as to cause the walls to fall down. In 85°, the Adriatic was entirely frozen over. In 892 and 898, the vines were killed by frost, and cattle died in their stalls. In 981, the winter lasted very long and was extremely severe. Everything was frozen over, and famine and pestilence closed the year. In 1207, the cold was so intense that most of the travelers in Germany were frozen to death on the roads. In 1233, it was excessively cold in Italy; the Po was frozen from Cremona to the sea, while the heaps of snow rendered the roads impassable; wine-casks burst, and trees split by frost with an immense noise. In 1234, a pine-forest was killed by frost at Ravenna. In 1236, the frost was intense in Scotland, and the Cattegat was frozen between Norway and Jutland. in 1282, the houses in Austria were covered with snow. In 1292, the Rhine was frozen; and in Germany 600 peasants were employed to clear the way for the Austrian army. In 1314, all the rivers in Italy were frozen. In 1384, the winter was so severe that the Rhine and Scheldt were frozen, and even the sea at Venice. In 1467, the winter was so severe in Flanders that the wine was cut with hatchets to be distributed to the soldiery. In 1580, the frost was very intense in England and Denmark; both the Little and Great Belt were frozen over. In 1694, many forest-trees and oaks in England were split with the frost. In 1592, the cold was so intense, that the starved wolves entered Vienna, and attacked both mien and cattle. The cold of 1540 was scarcely inferior to that of 1692, and the Zuyder-Zee was entirely frozen over. In 1776 much snow fell, and the Danube bore ice five feet thick below Vienna. In the winter of 1848-1849, the public journals recorded that the mercury, on one occasion, froze in the thermometers at Aggershuus, in Sweden. Now, as mercury freezes at 39° below zero, marked scientifically as -39°, that is, 71°below the freezing-point, we know that the temperature must have been at least as low as this-perhaps several degrees lower. And yet, as we shall afterwards shew, lower degrees of temperature even than this have been experienced by the Arctic voyagers. As might be expected, it is from the latter voyagers that we obtain some of the most interesting information concerning low temperatures. In the long and gloomy winter of the polar regions, the cold assumes an intensity of which we can form little conception. Mercurial thermometers often become useless; for when the mercury solidifies, it can sink no further in the tube, and ceases to be a correct indicator. As a more available instrument, a spirit-thermometer is then used, in which the place of mercury is supplied by rectified spirit of wine. With such thermometers, our Arctic explorers have recorded degrees of cold far below the freezing-point of mercury. Dr. Kane, the American Arctic explorer, in his narrative of the Grinnell Expedition in search of Franklin, records having experienced -42°on the 7th February 1851; that is, 74° of frost, or 3° below the freezing point of mercury. Let us conceive what it must have been to act a play, in a temperature only a few degrees above this! A week after the date last mentioned, the crew of the ship engaged in the expedition referred to, performed a farce called The Mysteries and Miseries of New York! The outside temperature on that evening was -36°; in the 'theater' it was -25° behind the scenes, and -2°in the audience department. One of the sailors had to enact the part of a damsel with bare arms; and when a cold flat-iron, part of the 'properties' of the theatre, touched his skin, the sensation was like that of burning with a hot-iron. But this was not the most arduous of their dramatic exploits. On Washington's birthday, February 22nd, the crew had another performance. The ship's thermometer outside was at -46° ; inside, the audience and actors, by aid of lungs, lamps, and hangings, got as high as -3°, only 62° below the freezing point-perhaps the lowest atmospheric record of a theatrical representation. It was a strange thing altogether. The condensation was so excessive, that we could barely see the performers; they walked in a cloud of vapour. Any extra vehemency of delivery was accompanied by volumes of smoke. Their hands steamed. When an excited Thespian took off his coat, it smoked like a dish of potatoes. Dr. Kane records having experienced as low a temperature as -53°, or 85° below the freezing point; but even this is surpassed in a register furnished by Sir Edward Belcher, who, in January 1854, with instruments of unquestioned accuracy, endured for eighty-four consecutive hours, a temperature never once higher than -5°. One night it sank to -591/4°; and on another occasion the degree of cold reached was -621/2°, or 941/2° below the freezing-point! Such narratives excite a curiosity to know how such intense cold can be borne by the human frame. All the accounts obtainable tend to shew that food, clothing, activity, and cheerfulness, are the four chief requisites. Dr. E. D. Clarke, the celebrated traveler, told Dr. Whiting that he was once nearly frozen to death-not in any remote polar region, but in the very matter-of-fact county of Cambridge. After performing divine service at a church near Cambridge, one cold Sunday afternoon in 1818, he mounted his horse to return home. Sleepiness came upon him, and he dismounted, walking by the head of his horse; the torpor increased, the reins dropped from his hand, and he was just about sinking probably never again to rise-when a passing traveler rescued him. This torpor is one of the most perilous accompaniments of extreme cold, and is well illustrated in the anecdote related of Dr. Solander in a previous article. Sir Edward Parry remarks, in reference to extremely low temperatures: Our bodies appeared to adapt themselves so readily to the climate, that the scale of our feelings, if I may so express it, was soon reduced to a lower standard than ordinary; so that after being for some days in a temperature of -15° or -20°, it felt quite mild and comfortable when the thermometer rose to zero that is, when it was 32 'below the freezing-point. On one occasion, speaking of the cold having reached the degree of-55°, he says: Not the slightest inconvenience was suffered from exposure to the open air by a person well clothed, so long as the weather was perfectly calm; but in walking against a very light air of wind, a smarting sensation was experienced all over the face, accompanied by a pain in the middle of the forehead, which soon became rather severe. As a general remark, Parry on another occasion said: We find it necessary to use great caution in handling our sextants and other instruments, particularly the eye-pieces, of telescopes, which, if suffered to touch the face, occasioned an intense burning pain. Sir Leopold M'Clintock, while sledging over the ice in March 1859, trudged with his men eight hours at a stretch, over rough hummocks of ice, without food or rest, at a temperature of -48°, or eighty degrees below the freezing-point, with a wind blowing too at the time. In one of the expeditions a sailor incautiously did some of his outdoor work without mittens; his hands froze; one of them was plunged into a basin of water in the cabin, and the intense cold of the hand instantly froze the water, instead of the water thawing the hand! Poor fellow: his hand required to be chopped off. Dr. Kane, who experienced more even than the usual share of sufferings attending these expeditions, narrates many anecdotes relating to the cold. One of his crew put an icicle at-28° into his mouth, to crack it; one fragment stuck to his tongue, and two to his lips, each taking off a bit of skin-burning it off, if this term might be used in an inverse sense. At -25°: the beard, eyebrows, eye-lashes, and the downy pubescence of the ears, acquire a delicate, white, and perfectly enveloping cover of venerable hoar-frost. The moustache and under-lip form pendulous beads of dangling ice. Put out your tongue, and it instantly freezes to this icy crusting, and a rapid effort, and some hand-aid will be required to liberate it. Your chin has a trick of freezing to your upper jaw by the luting aid of your beard; my eyes have often been so glued, as to shew that even a wink may be unsafe. In reference to the torpor produced by extreme cold, Dr. Kane further remarks: 'Sleepiness is not the sensation. Have you ever received the shocks of a magneto-electric machine, and had the peculiar benumbing sensation of 'Can't let go,' extending up to your elbow joints? Deprive this of its paroxysmal character; subdue, but diffuse it over every part of the system-and you have the so-called pleasurable feelings of incipient freezing.' One day he walked himself into 'a comfortable perspiration, 'with the thermometer seventy degrees below the freezing -point. A breeze sprang up, and instantly the sensation of cold was intense. His beard, coated before with icicles, seemed to bristle with increased stiffness; and an unfortunate hole in the back of his mitten 'stung like a burning coal. 'On the next day, while walking, his beard and moustache became one solid mass of ice. 'I inadvertently put out my tongue, and it instantly froze fast to my lip. This being nothing new, costing only a smart pull and a bleeding afterwards, I put up my mittened hands to 'blow hot,' and thaw the unruly member from its imprisonment. Instead of succeeding, my mitten was itself a mass of ice in a moment; it fastened on the upper side of my tongue, and flattened it out like a batter-cake between the two disks of a hot gridle. It required all my care with the bare hands to release it, and then not without laceration.' The following remarkable instances of the disastrous results of extreme cold in Canada are related by Sir Francis Head: 'I one day inquired of a fine, ruddy, honest-looking man, who called upon me, and whose toes and insteps of each foot had been truncated, how the accident happened? He told me that the first winter he came from England, he lost his way in the forest, and that after walking for some hours, feeling pain in his feet, he took off his boots, and from the flesh immediately swelling, he was unable to put them on again. His stockings, which were very old ones, soon wore into holes, and as rising on his insteps he was hurriedly proceeding he knew not where, he saw with alarm, but without feeling the slightest pain, first one toe and then another break off, as if they had been pieces of brittle stick; and in this mutilated state he continued to advance till he reached a path which led him to an inhabited log-house, where he remained suffering great pain till his cure was effected. On another occasion, while an Englishman was driving, one bright beautiful day, in a sleigh on the ice, his horse suddenly ran away, and fancying he could stop him better without his cumbersome fur-gloves than with them, he unfortunately took them off. As the infuriated animal at his utmost speed proceeded, the man, who was facing a keen northwest wind, felt himself gradually, as it were, turning into marble; and by the time he stopped, both his hands were so completely and so irrecoverably frozen, that he was obliged to have them amputated.' Englishmen, take them one with another, bear up against intense cold better than against intense heat, one principal reason being, that the air is in such circumstances less tainted with the seeds of disease. They are then more lively and cheerful, feel themselves necessitated to active and athletic exertion, and become, consequently, better able to combat the adverse influences of a low degree of temperature. |