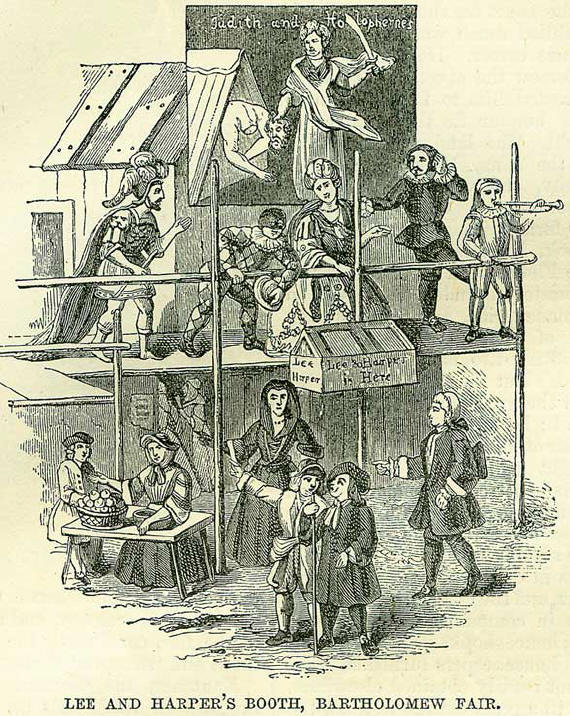

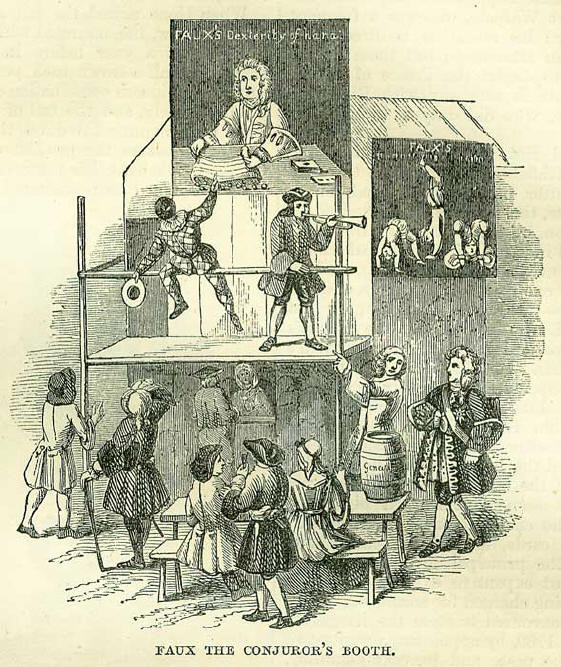

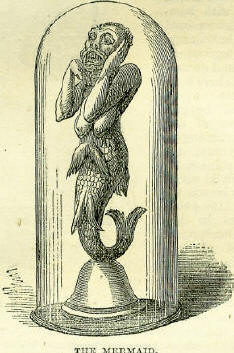

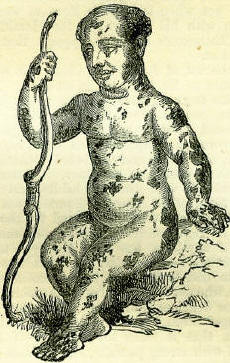

24th AugustBorn: Letizia Bonaparte (née Ramolini), mother of Napoleon, 1750, Ajaccio, Corsica; William Wilberforce, philanthropist and religious writer, 1759, Hull. Died: Cneius Julius Agricola, Roman general, 93, Rome; Alphonso V, of Portugal, 1481, Cintra; Admiral Gaspard de Coligni, murdered at Paris, 1572; Colonel Thomas Blood, noted for his attempt to steal the regalia from the Tower, 1680; John, Duke of Lauderdale, minister of Charles II, 1682; Dr. John Owen, eminent divine, 1683, Ealing; Theodore Hook, novelist, 1841. Feast Day: St. Bartholomew, apostle. The Martyrs of Utica, or The White Mass, 258. St. Ouen or Audoen, archbishop of Rouen, confessor, 683. St. Irchard or Erthad, bishop and confessor in Scotland, 10th century. ST. BARTHOLOMEWOne of the twelve apostles, is believed to have travelled on a mission into Armenia, and to have there suffered martyrdom by being flayed alive. A knife, consequently, became the emblem of St. Bartholomew, as may be seen on many of the old clog almanacks, described in a former part of this work. At the abbey of Croyland, there used to be a distribution of knives each St. Bartholomew's Day, in honour of the saint. The insetting of chilly evenings is noted at this season of the year, and has been expressed in a popular distich: St Bartholomew Brings the cold dew. THEODORE HOOKIf fine personal qualities, as a handsome figure and agreeable countenance, quick intelligence and brilliant wit, with an unfailing flow of animal spirits, were alone able to secure happiness, Theodore Hook ought to have been amongst the happiest and most fortunate of mankind, for he possessed them all. We know, however, that something more is needed-above all, conscientiousness, sense of duty, or at least common prudence-to make life a true success. No man could more thoroughly illustrate the vanity of all gifts where this is wanting, than Theodore Hook. His early days were spent in an atmosphere which naturally tended to foster and develop his peculiar genius. His father was a favourite musical composer, whose house was the resort of all the popular characters of the day-musical, theatrical, and otherwise. Theodore was found to have an exquisite ear for music, and soon became noted among his father's coteries as a first-rate singer and player on the pianoforte. One night he astonished the old gentleman by singing and accompanying on the instrument two songs, one serious and the other comic, which the latter had never heard before. On inquiry, they turned out to be original compositions, both as regarded words and music. Here an assistant was unexpectedly discovered, by the elder Hook, to aid him in his labours, as hitherto he had always been obliged to employ the services of some poetaster to furnish the libretto of his musical pieces. Thus encouraged, Theodore set to work, and produced The Soldier's Return; or, What can Beauty do? a comic opera, in two acts, first represented at Drury Lane in 1805. Its success was such as to stimulate him to further efforts, and at the age of sixteen he became a successful dramatist and songwriter, the pet of the coulisscs and green-room, to which he had a free entrée; and the recipient of a handsome income, rarely procurable by a man's personal exertions at so early an age. The pieces written by him at this period comprise Catch Him, Who Can; The Invisible Girl; Tekeli, or the Siege of Mongratz; Killing no Murder, and others; but few, if any, of these now keep possession of the stage. As may have been expected, the more solid branches of education seem to have been little attended to in the case of Hook. The first school to which he was sent, was a 'seminary for young gentlemen' in Soho Square, where, by his own account, he used regularly to play the truant, amusing himself by wandering about the streets, and devising all sorts of excuses to account to his teacher for his absence. On one occasion, unfortunately for him, he had remained at home, asserting to his parents that a general holiday had been granted to the scholars. His brother on the same day, which happened to be the rejoicing for the peace of Amiens, was passing Theodore's school, and seeing it open, was induced to go in and make inquiries, from which he learned that the young vagabond had not shown face there for the last three weeks. The result was his being locked up for the remainder of the day in the garret, and debarred from seeing the illuminations and fire-works in the evening. From this academy he was sent to a school in Cambridgeshire, and afterwards to Harrow, where he had Lord Byron and Sir Robert Peel for his companions, but made little progress in classic learning, study and application being to him a most irksome drudgery. On the death of his stepmother in 1802, he was pre-maturely withdrawn from school, and from this period remained at home, in the enjoyment of the congenial atmosphere of his father's house, and the reputation and more solid advantages which the brilliancy of his talents enabled him to secure. Hook's turn for quizzing and practical jokes was very early displayed; and innumerable anecdotes are recorded of this propensity. They are connected chiefly with the theatre, to which his occupations constantly led him, and where he was the soul and mirth-inspirer of the motley community behind the scenes. On one occasion he nearly frightened Dowton, the comedian, out of his wits, by walking up to him instead of the proper personator of the part, and delivering a letter. On another, when Sheridan was contesting the seat for Westminster, the cry of 'Sheridan for ever!' was heard by the astonished audience proceeding apparently from the evil spirit in the 'Wood-Demon,' and producing one of those incongruous effects which are so much relied on for raising a laugh in pantomime or burlesque. A mischievous trick of another kind, in which he was aided by Liston, may also be mentioned. A young gentleman of Hook's acquaintance had a great desire to witness a play, and also escort a fair cousin thither, but was terrified lest his going to a theatre should come to the knowledge of his father, a rigid Presbyterian, who held such places in abhorrence. He communicated his difficulties to his gay friend. 'Never mind the governor, my dear fellow,' was the reply; 'trust to me; I'll arrange everything -get you a couple of orders, secure places-front row; and nobody need know anything about it.' The tickets were procured, and received with great thankfulness by Mr. B-, who started with his relative for the playhouse, and the pair soon found themselves absorbed in an ecstasy of delight in witnessing the drolleries of Liston. But what was their confusion when the comedian, advancing to the foot-lights during a burst of laughter at one of his performances, looked round the dress-circle with a mock-offended air, and exclaimed: 'I don't understand this conduct, ladies and gentlemen! I am not accustomed to be laughed at; I can't imagine what you can see ridiculous in me; why, I declare' (pointing at the centre box with his finger), 'there's Harry B-, too, and his cousin Martha J-; what business have they to come here and laugh at me, I should like to know? I'll go and tell his father, and hear what he thinks of it! The consternation caused to the truant couple by this unexpected address, and the eyes of the whole audience being turned on them, may be more readily imagined than described, and they fled from the house in dismay. In the days of which we write, the abstraction of pump-handles and street-knockers was a favourite amusement of the young blades about town, some of whom prided themselves not a little in forming a museum of these trophies. Hook was behind no one in such freaks. One of them was the carrying off the figure of a Highlander, as large as life, from the door of a tobacconist, wrap-ping it up in a cloak, and tumbling it into a hackney-coach as ' a friend, a very respectable man, but a little tipsy,' with a request to the coachman to drive on. The following anecdote is related in the Ingoldsby Legends, but will well bear repetition. On the occasion of the trial of Lord Melville, Hook had gone with a friend to Westminster Hall to witness the proceedings. As the peers began to enter, a simple-looking lady from the country touched his arm, and said: 'I beg your pardon, sir, but pray who are those gentlemen in red now coming in?' 'Those, ma'am,' he replied, 'are the barons of England; in these cases, the junior peers always come first.' 'Thank you, sir, much obliged to you. Louisa, my dear (turning to her daughter, who accompanied her), tell Jane these are the barons of England; and the juniors (that's the youngest, you know) always goes first. Tell her to be sure and remember that when we get home.' 'Dear me, ma,' said Louisa, 'can that gentleman be one of the youngest? I am sure he looks very old.' This naivete held out an irresistible temptation to Theodore, who, on the old lady pointing to the bishops, who came next in order, with scarlet and lawn sleeves over their doctors' robes, and asking, 'What gentlemen are those?' replied: 'Gentlemen, ma'am! these are not gentlemen; these are ladies, elderly ladies-the dowager-peeresses in their own right.' His interrogator looked at him rather suspiciously, as if to find out whether or not he was quizzing her; but reassured by the imperturbable air of gravity with which her glance was met, turned round again to her daughter, and whispered: 'Louisa, dear, the gentleman says that these are elderly ladies and dowager-peeresses in their own right; tell Jane not to forget that.' Shortly afterwards, her attention was drawn to the speaker of the House of Commons, with his richly-embroidered robes. 'Pray, sir,' she exclaimed, 'who is that fine-looking person opposite?' 'That, ma'am, is Cardinal Wolsey.' 'No, sir!' was the angry rejoinder, 'we knows a good deal better than that; Cardinal Wolsey has been dead and buried these many years.' 'No such thing, my dear madam,' replied Hook, with the most extraordinary sang froid; 'it has indeed been so reported in the country, but with-out the least foundation in truth; in fact, these rascally newspapers will say anything!' The good lady looked thunderstruck, opened her eyes and mouth to their widest compass, and then, unable to say another word, or remain longer on the spot, hurried off with a daughter in each hand, leaving the mischievous wag and his friend to enjoy the joke. A well-known story is told of Hook and Terry the actor making their way into a gentleman's house with whom they had no acquaintance what-ever, but the appetising steams issuing from whose area gave indications of a glorious feast being in the course of preparation. The anecdote is perfectly true, though the real scene of the adventure was not, as commonly represented, a suburban villa on the banks of the Thames, but a town-mansion some-where in the neighbourhood of Soho Square. Hook caught at the idea suggested by Terry, that he should like to make one of so jovial a party; and arranging with his friend that he should call for him there that evening at ten o'clock, hurried up the steps, gave a brisk rap with the knocker, and was at once admitted to the drawing-room. The room being full, no notice was taken of him at first, and before the host discovered him, he had already made his way to the hearts of a knot of guests by his sallies of drollery. The master of the house at last perceiving a stranger, went up, and politely begged his name, as he felt rather at a loss. Hook replied with a perfect torrent of volubility, but expressed in the suavest and mostfascinating terms, and effectually preventing any interruption to his discourse. An explanation at last came out, that he had mistaken both the house and the hour at which he ought to have dined with a friend. The old gentleman's civility then could not allow him to depart, as his friend's dinner-hour must now be long past, and a guest with such a flow of spirits must prove a most agreeable acquisition to his own table. Hook professed great reluctance to trespass thus on the hospitality of a perfect stranger, but was induced, seemingly with much difficulty, to remain, and partake of dinner. So delightful a companion and so droll a fellow had never been met before, and so much mirth and jollity had never till now enlivened the mansion. At ten o'clock, Mr. Terry was announced, and Hook, who had seated himself at the pianoforte, in the performance of one of his famous extemporaneous effusions, brought his song to a close as follows: I am very much pleased with your fare; Your cellar's as prime as your cook; My friend's Mr. Terry the player, And I'm Mr. Theodore Hook! Nor was this by any means the only entertainment of the kind which his assurance and farcical powers enabled him to obtain. Passing one day in a gig with a friend by the villa of a retired chronometer-maker, he suddenly reined up, re-marked to his friend what a comfortable little box that was, and that they might do worse than dine there. He then alighted, rang the bell, and on being admitted to the presence of the worthy old citizen, said that he had often heard his name, which was celebrated throughout the civilised world, and that being in the neighbourhood, he could not resist the temptation of calling and making the acquaintance of so distinguished a public character. The good man was quite tickled with the compliment; pressed his admirer and friend to stay dinner, which was just ready; and a most jovial afternoon was spent, though on the way home the gig containing Hook and his companion was smashed to pieces by the refractory horse, and the two occupants had a narrow escape of their lives. Another of his adventures, in which he seems to have taken his cue from Tony Lumpkin, was driving up to an old gentleman's house, ordering the servant who appeared to take his mare to the stable and rub her down well, and then proceeding to the parlour, stretched himself at full-length on the sofa, and called for a glass of brandy and water. On the master of the house making his appearance and inquiring the business of his visitor, Hook became more vociferous than ever, declared that he had never before met with such treatment in any inn, or from any landlord, and ended by saying that his host must be drunk, and he should certainly feel it his duty to report the circumstance to the bench. The old gentleman was confounded, but in a short time Hook pretended to discover his blunder of having taken the house for an inn, and made ten thousand apologies, adding that he had been induced to commit the mistake by seeing over the entrance-gate a large vase of flowers, which, he imagined, indicated the sign of the Flower-pot. This said vase happened to be cherished by its owner with special complacency as a most unique and chaste ornament, and here was it degraded to the level of a pot-house sign! Another story is told of Hook, in which. he improved on a well-known device related of Sheridan. Getting into a hackney-coach one day, and being unable to pay the fare, he bethought himself of the plan adopted by the celebrated wit just mentioned on a similar occasion, and hailed a friend whom he observed passing along the street. He made him get into the carriage beside him, but on comparing notes he found his companion equally devoid of cash as himself, and it was necessary to think of some other expedient. Presently they approached the house of a celebrated surgeon. Hook alighted, rushed to the door, and exclaimed hurriedly to the servant who opened it: 'Is Mr. -- at home? I must see him immediately. For God's sake do not lose an instant.' Ushered into the consulting-room, he exclaimed wildly to the surgeon: ' Thank heaven! Pardon my incoherence, sir; make allowance for the feelings of a husband, perhaps a father-your attendance, sir, is instantly required-instantly-by Mrs. -. For mercy's sake, sir, be off.' 'I'll be on my way immediately,' replied the medical man. ' I have only to get my instruments, and step into my carriage.' 'Don't wait for your carriage,' cried the pseudo-distressed parent; 'get into mine, which is waiting at the door.' Esculapius readily complied, was hurried into the coach, and conveyed in a trice to the residence of an aged spinster, whose indignation and horror at the purport of his visit was beyond all bounds. The poor man was glad to beat a speedy retreat, but the fury of the old maiden-lady was not all he was destined to undergo, as the hackney-coachman kept hold of him, and mulcted him in the full amount of the fare which Hook ought to have paid. All these and similar escapades, however, were fairly eclipsed by the famous Berners-street hoax, which created such a sensation in London in 1809. By despatching several thousands of letters to innumerable quarters, he completely blocked up the entrances to the street, by an assemblage of the most heterogeneous kind. The parties written to had been requested to call on a certain day at the house of a lady, residing at No. 54 Berners Street, against whom Hook and one or two of his friends had conceived a grudge. So successful was the trick, that nearly all obeyed the summons. Coal-wagons, heavily laden, carts of upholstery, vans with pianos and other articles, wedding and funeral coaches, all rumbled through, and filled up the adjoining streets and lanes; sweeps assembled with the implements of their trade; tailors with clothes that had been ordered; pastry-cooks with wedding cakes; undertakers with coffins; fishmongers with cod-fishes, and butchers with legs of mutton. There were surgeons with their instruments; lawyers with their papers and parchments; and clergymen with their books of devotion. Such a babel was never heard before in London, and to complete the business, who should drive up but the lord mayor in his state-carriage; the governor of the Bank of England; the chair-man of the East India Company; and even a scion of royalty itself, in the person of the Duke of Gloucester. Hook and his confederates were meantime enjoying the fun from a window in the neighbourhood, but the consternation occasioned to the poor lady who had been made the victim of the jest, was nearly becoming too serious a matter. He never avowed himself as the originator of this trick, though there is no doubt of his being the prime actor in it. It was made the subject of a solemn investigation by many of the parties who had been duped, but so carefully had the precautions been taken to avoid detection, that the inquiry proved entirely fruitless. In 1813, Hook received the appointment, with a salary of £2000 a year, of accountant-general and treasurer of the Mauritius, an office which one would have supposed to be the very antipodes to all his capacities and predilections. How it came to be conferred on him, does not clearly appear; but it exhibits a memorable instance, among others, of the reckless selection, too often displayed in those days, in the choice of public officials. What might have been 'expected followed. The treasurer was about as fitted by nature for discharging the duties of such an office as a clown in a pantomime, and the five years spent by him in the island were little more than a round of merriment and festivities. An investigation of his accounts at last took place, and a large deficit, ultimately fixed at about £12,000, was discovered. There seems no reason for believing that Hook had been guilty of the least embezzlement or mat-appropriation of the government funds; but there can be no doubt that his negligence in regard to his duties was most reprehensible, trusting their performance entirely to a deputy, who committed suicide about the time of the inquiry being instituted. A criminal charge was made out against the unfortunate accountant-general, and in 1818, he was sent home under arrest. His buoyancy of spirits, however, never failed him, and meeting at St. Helena one of his old friends, who asked him if he was going home for his health, he replied: 'Yes, I believe there's something wrong with the chest!' On landing in England, it was found that there was no ground for a criminal action against him, but that as responsible for the acts of his deputy, his person and estate were amenable to civil proceedings. The whole of his property in the Mauritius and elsewhere was accordingly confiscated, and he underwent a long confinement, first in a sponging-house in Shire-Lane, and afterwards in the King's Bench Prison. Thrown again on his own resources, he produced several dramatic pieces, which achieved a respectable amount of success. The great event, however, at this period of his life, was his becoming editor of the John Bull news-paper, which, under his management, made itself conspicuous by its stinging and too often scurrilous attacks on the Whig party. An inexhaustible fund of metrical lampoon and satire was ever at the command of its conductor, and he certainly dealt out his sarcasm with no sparing hand. Some of the most famous of his effusions were directed against Queen Caroline and her party at the time of the celebrated trial. Whyttington and his Catte, the Hunting of the Hare, and Mrs. Muggins's Visit to the Queen, were reckoned in their day by the Tories as uncommonly smart things. Have you been to Brandenburgh? heigh! ma'am, ho! ma'am; Have you been to Brandenburgh! ho! 0 yes! I have been, ma'am, to visit the queen, ma'am, With the rest of the gallantee show. What did you see, ma'am? heigh! ma'am, ho! ma'am, What did you see, ma'am? ho! We saw a great dame, with a face as red as flame, And a character spotless as snow. Mrs. Muggins's Visit was a satire on Queen Caroline's drawing-room, at Brandenburgh House, and is said to be a very good specimen of Hook's style in improvisation, an art which he possessed in a wonderful degree. Some years before Hook's obtaining his disastrous appointment at the Mauritius, he had published, under an assumed name, a novel entitled The Man of Sorrow, but its success was very doubtful. It was not till after he had passed through the furnace of adversity, and undergone the pains of incarceration, that he gave to the world that series of works of fiction which, prior to the days of Dickens and Thackeray, had so unbounded a popularity as the exponents of middle-class life. With great smartness and liveliness of description, they partake eminently of the character of the author whose gifts were much more brilliant than solid. Deficient in the latter element, and possessing, in a great measure, an ephemeral interest, it becomes, therefore, doubtful whether they will be much heard of in a succeeding generation. The bons mots recorded of Theodore Hook are multifarious, but they have all more or less a dash of the flippancy and impudence by which, especially in early life, he was characterised. Walking along the Strand one day, he accosted, with much gravity, a very pompous-looking gentleman. 'I beg your pardon, sir, but may I ask, are you anybody particular?' and passed on before the astonished individual could collect himself sufficiently to reply. In the midst of his London career of gaiety, when a stripling, he was induced by his brother James, who was seventeen years his senior, to enter him-self at St. Mary's Hall, Oxford, where his sojourn, however, was but brief. On being presented for matriculation to the vice-chancellor, that dignitary inquired if he was prepared to sign the Thirty-nine Articles. 'O yes,' replied Theodore, 'forty, if you like!' It required all his brother's interest with Dr. Parsons to induce him to pardon this petulant sally. The first evening, it is said, of his arrival at Oxford, he had joined a party of old schoolfellows at a tavern, and the fun had become fast and furious. Just then the proctor, that terror of university evil-doers, made his appearance, and advancing to the table where Hook was sitting, addressed him with the customary question: 'Pray, sir, are you a member of this university?' 'No, sir,' was the reply (rising and bowing respectfully); 'pray, sir, are you?' Somewhat discomposed by this unexpected query, the proctor held out his sleeve, 'You see this, sir?' 'Ah,' replied the young freshman, after examining with much apparent interest for a few moments the quality of the stuff. 'Yes, I perceive, Manchester velvet; and may I take the liberty, sir, of inquiring how much you may have paid per yard for the article?' Discomfited by so much imperturbable coolness, the academical dignitary was forced to retire amid a storm of laughter. The Mauritius affair proved a calamity, from the effects of which Hook never recovered. With a crushing debt constantly suspended in terrorem over him, and an enfeebled frame, the result of his confinement in prison, and partly also of the unwholesome style of living, as regards food, in which he had indulged when abroad, his last years were sadly embittered by ill health, mental depression, and pecuniary embarrassment. Outwardly, he seemed still to enjoy the same flow of spirits; but a worm was gnawing at the heart, and his diary at this period discloses a degree of mental anguish and anxiety which few of those about him suspected. He died at Fulham, on 24th August 1841, in his fifty-third year. THE ST. BARTHOLOMEW MASSACREThe prodigious event bearing this well-known name, was mainly an expression of the feelings with which Protestantism was regarded in France in the first age after the Reformation; but the private views of the queen-mother, the atrocious Catherine de Medici, were also largely concerned. After the death of her husband, Henry II, she had an incessant struggle, during the reigns of the boy-kings, her sons, who succeeded, for the supreme power. It seemed within her grasp, but for the influence which the Protestant leader, the Admiral Coligni, had acquired over the mind of Charles IX. This young monarch was a semi-maniac. He was never happy but when taking the most violent exercise, riding for twelve or fourteen hours consecutively, hunting the same stag for two or three days, only stopping to eat, and reposing but a few hours in the night. He had, during the absence of Catherine, listened to Coligni, and agreed to an expedition against the Spaniards in alliance with the Prince of Orange. When the proud mother returned, she found herself supplanted by the chief of the Huguenot party, whose triumph in her eyes would be absolute ruin to her family. The king had accepted the idea of war with delight; he demanded the constant presence of the admiral, and kept him half the night in his bedroom, calculating the number of his armies, and laying down plans for marching. From this moment the death of the Protestant leader was determined on. The opportunity of the marriage between Henry of Navarre and the Princess Margaret, which took place on the 18th of August 1572, was seized upon; the Huguenots of rank had followed their leader to Paris; a gallery was erected for them outside Notre Dame, that their prejudices might not be wounded, and nothing was seen but festivity and concord between the disagreeing parties. But on the 22nd, Coligni was shot at from a window by a follower of the Duke de Guise, and wounded in two places; his party were highly indignant at the outrage, crowded round the house, and threats of vengeance were heard; these were used by the king's relatives to convince him that he and all about him were in danger of immediate destruction, if he did not permit a general massacre. The Dukes de Guise, Anjou, Aumale, and others agreed to carry out the dreadful decree; the bell of St. Germain de l'Auxerrois was to toll out the signal in the dead of the night. From a balcony in the Louvre, which opened out of the ball-room, and looked into the Seine, the guilty mother and trembling son watched the proceedings. The house where Coligni lay wounded was first attacked; he met his fate with the heroism of a Christian hero; his body was thrown from the window, and his followers shared the same fate. All the streets in Paris rang with the dreadful cry: 'Death to the Huguenot! kill every man! kill! kill!' Neither men, women, nor children were spared; some asleep, some kneeling in supplication to their savage assailants; about thirty thousand innocent persons were thus butchered by a furious mob, allowed to give vent to their fanatical passion. All that day it continued; towards evening the king sent out his trumpeter to command a cessation; but the people were not so easily controlled, and murders were committed during the two following days. Five hundred men of rank, with many ladies of equally high birth, and ministers of religion, were among the victims; every man, indeed, might kill his personal enemy without inquiry being made as to his religion, and Catholics suffered as well as Huguenots. The large cities of the provinces, Rouen, Lyon, &c., caught the infection, which the queen-mother took no steps to prevent, and France was steeped in blood and mourning. The king at first laid the blame on the Houses of Guise and Coligni, but he afterwards went to the parliament, and acknowledged himself as the author, claiming the merit of having given peace to France by the destruction of the Protestants. But his life was ever after one of bitter remorse and horror. Not many days after, he said to his surgeon: 'I feel like one in a fever, my body and mind are both disturbed; every moment, whether asleep or awake, visions of murdered corpses, covered with blood, and hideous to the sight, haunt me. Oh, I wish they had spared the innocent and imbecile!' In less than two years, the unfortunate young king had joined his victims; a prey to every mental and physical suffering that could be imagined. The black turpitude and wickedness of the Bartholomew Massacre is very obvious; but it is not less true that it was a great blunder. The facts were heard of all over Europe with a shudder of horror. They have been a theme of reproach against Catholics ever since. It may be considered as a serious misfortune for any code of opinions whatever to have such a terrible affair associated with it. THE BARTHOLOMEW ACT, 1662When High Church had the upper hand in the reign of Charles I, it did not scruple to pillory the Puritans, excise their ears, and banish them. When the Puritans got the ascendancy afterwards, they treated high-churchmen with an equally conscientious severity. At the Restoration, all the reforming plans of the last twenty years were found utterly worn out of public favour, and the public submitted very quietly to a reconstitution of the church under what was called the Act of Uniformity, which made things very unpleasant once more for the Puritans. By its provisions, every clergyman was to be expelled from his charge on the 24th of August 1662, if, by that time, he did not declare his assent to everything contained in the revised Book of Common Prayer; every clergy-man who, during the period of the Commonwealth, had been unable to obtain episcopal ordination, was commanded now to obtain that kind of sanction; all were to take an oath of canonical obedience; all were to give up the theory on which the old 'Solemn League and Covenant' had been based; and all were to accept the doctrine of the king's supremacy over the church. The result was, that two thousand of the clergy signalised this Bartholomew Day by coming out of the church. Baxter, Alleyne, Calamy, Owen, and Bates, were among them; while Milton, Banyan, and Andrew Marvell, were among the laymen who adhered to their cause. The act became the more harsh from its coming into operation just before one whole year's tithes were due. Two thousand families, hitherto dependent on stipends for support, were driven hither and thither in the search for a livelihood; and this was rendered more and more difficult by a number of subordinate statutes passed in rapid succession. The ejected ministers were not allowed to exercise, even in private houses, the religious functions to which they had been accustomed. Their books could not be published without episcopal sanction, previously applied for and obtained. A statute, called the 'Conventicle Act,' punished with fine, imprisonment, or transportation, every one present in any private house where religious worship was carried on-if the total number exceeded by more than five the regular members of the household. Another, called the 'Oxford Act,' imposed on these unfortunate ministers an oath of passive obedience and non-resistance; and if they refused to take it, they were prohibited from living within five miles of any place where they had ever resided, or of any corporate town, and from eking out their scanty incomes by keeping schools, or taking in boarders. A second and stricter version of the Conventicle Act deprived the ministers of the right of trial by jury, and empowered any justice of the peace to convict them on the oath of a single informer, who was to be rewarded with one-third of the fines levied; no flaw in the legal document, called the mittimus, was allowed to vitiate it; and the 'benefit of the doubt,' in any uncertain cases, was to be given to the accusers, not to the accused. Writers who take opposite sides on this subject naturally differ as to the causes and justification to be assigned for the ejection; but there is very little difference of opinion as to the misery suffered during the years intervening between 1662 and 1688. Those who, in one way or other, suffered homelessness, hunger, and penury on account of the Act of Uniformity and the ejection that followed it, have been estimated at 60,000 persons, and the amount of pecuniary loss at twelve or fourteen millions sterling. Defoe, Penn, and other contemporary writers, set down up-wards of 5000 Nonconformists as the number who perished within the walls of prisons; and many, like Baxter, were hunted from house to house, from chapel to chapel, by informers, whose only motive was to obtain a portion of the fines levied for infringement of numerous statutes. Considered as a historical fact, dissent may be said to have begun in England on this 24th August 1662, when the Puritans, who had before formed a body within the church, now ranged themselves as a dissenting or Nonconformist sect outside it. BARTHOLOMEW FAIRThe great London Saturnalia-the Smithfield fair on the anniversary of St. Bartholomew's Day -died a lingering death in 1855, after flourishing for seven centuries and a half. Originally established for useful trading purposes, it had long survived its claim to tolerance, and as London increased, had become a great public nuisance, with its scenes of riot and obstruction in the very heart of the city. When Rahere, minstrel and jester to Henry I, left the gaieties of the court for the proprieties of the cloister, he exhibited much worldly prudence in arranging his future career. He affirmed that he had seen Bartholomew the apostle in a vision, and that he had directed him to found a church and hospital in his honour in the suburbs of London, at Smithfield. The land was the more readily granted by the king, Henry II; for it was waste and marshy, and would be improved by the proposed foundation. Osier Lane (now spelled in Cockney form with an H) marks the site of a small brook, lined with osiers, which emptied itself in the Fleet River. The marsh was drained, and the monastery founded on its site in 1123; Rahere was made prior, and great success attended the shrine of St. Bartholomew, where many miracles were affirmed to have been effected in aid of the afflicted. But the new prior, having been an active man of the world, looked to temporal as well as spiritual aid; he therefore included the right to hold a great fair on the festival of his patron saint, and this brought traders from all parts to Smithfield, for they had the royal safeguard-' firm peace to all persons coming to and returning from the fair'-during the three days it was held. Cattle and merchandise were the staple of such fairs. The safe-guard given to traders in days when travelling was difficult and dangerous, and the ease with which men might combine to go in companies to them, made them generally useful; hence shopkeepers laid in their stock from them, and housekeepers furnished their homes with articles not readily obtained elsewhere. The pious might join in a great church-festival, the pleasure-seekers find amusement in the wandering minstrels and jesters who were drawn to the busy scene, or stare with wonder at some performing monkey or other 'outlandish beast,' who were sure to find favour with the sight-loving Londoners.  Several centuries elapsed, and the whole character of English life altered, before the trading fair became exclusively a pleasure-fair. It was not until the cessation of our civil wars, and the quiet establishment of the House of Tudor upon the throne, that trade assumed its important position, and commercial enterprise elevated and enlarged its boundaries. In the reign of Queen Elizabeth, Bartholomew Fair ceased to be a cloth-fair of any importance; but its name and fame is still preserved in the lane running parallel to Bartholomew Close, termed 'Cloth-fair,' which was generally inhabited by drapers and mercers' in the days of Strype, and which still preserves many antique features, and includes, in a somewhat modernised form, some of the old houses founded by Lord Rich and his successors, who obtained the grant f the hospital property in the reign of Henry VIII. The fair was always proclaimed bythe lord mayor, beneath the arch shown in our cut, to the very end of its existence; and its original connection with the cloth trade was also shown in a burlesque proclamation the evening before by a company of drapers and tailors, who met at 'the Hand and Shears,' a house-of-call for their fraternity in Cloth-fair, from whence they marched, shears in hand, to this archway, and announced the opening of the fair, concluding the ceremony by a general shout and 'snapping of shears.' Keutzner, the German traveller, who visited England in 1598, tells us, 'that every year, upon St. Bartholomew's Day, when the fair is held, it is usual for the mayor, attended by the twelve principal aldermen, to walk in a neighbouring field, dressed in his scarlet gown, and about his neck a golden chain.' A tent was pitched for their accommodation, and wrestling provided for their amusement. 'After this is over, a parcel of live rabbits are turned loose among the crowd, which are pursued by a number of boys, who endeavoured to catch them with all the noise they can make.' The next vivid picture of the fair we obtain from an eye-witness, shows how great the change in its character during the progress of the reign of Elizabeth. This photograph of the fair in 1614, we obtain in Ben Jonson's comedy, which takes its title from, and is supposed to be chiefly enacted in, the precincts of the fair. There was hardly a trace now left of its old business character-it was all eating, drinking, and amusement. It had become an established custom to eat roast-pig here; shows were established for the exhibition of 'motions' or puppet-plays, sometimes constructed on religious history, such as 'the Fall of Nineveh,' 'the History of the Chaste Susanna,' &c.; others were constructed in classic story, as the Siege of Troy,' or 'the Loves of Hero and Leander;' which is enacted in the last act of Ben Jonson's play, and bears striking resemblances to the burlesques so constantly played in our modern theatres. Shows of other kinds abounded, and zoology was always in high favour. One of Ben's characters says: 'I have been at the Eagle and the Black Wolf, and the Bull with the five legs, and the Dogs that dance the Morrice, and the Hare with the Tabor.' Some of these performances are. still popular 'sights:' the hare heating the tabor amused our Anglo-Saxon forefathers, as it may amuse generations yet unborn. Over-dressed dolls ('Bartholomew-Fair babies'), and `gilt gingerbread,' with drums, trumpets, and other toys were abundantly provided for children's' 'fairings. In 1641, the fair had increased greatly, and become solely devoted to pleasure -such as it was. In a descriptive tract of that date, we are told it was 'of so vast an extent that it is contained in no less than four several parishes-namely, Christ-church, Great and Little St. Bartholomew's, and St. Sepulehre's. Hither resort people of all sorts and conditions. Christ church cloisters are now hung full of pictures. It is remarkable, and worth your observation to behold, and hear the strange sights, and confused noise in the fair. here, a knave, in a fool's coat, with a trumpet sounding, or on it drum heating, invites you to see his puppets; there, a rogue like a wild woodman, or in an antic shape like an incubus, desires your company to view his motion; on the other side, Hocuspocus, with three yards of tape or ribbon in his hand, thews his art of legerdemain to the admiration and astonishment of a company of cockloaches. Amongst these, you shall. see a gray goose-cap (as wise as the rest), with a 'what do ye lacks.) 'in his month, stand in his booth, slinking it rattle or scraping a fiddle, with which children are so taken, that they presently cry out for these fopperies; and all these together make such a distracted noise, that you would think Babel not comparable to it.' In the reign of Charles II, the fair became a London carnival of the grossest kind. The licence was extended front three to fourteen days, the theatres were closed dining this time, and the actors brought to Smithfield. All classes, high and low, visited the place. Evelyn records his visit there, so does John Locke, and garrulous Pepys went often. On August 28, 1667, he notes that he 'went twice round Bartholomew Fair, which I was glad to see again: Two days afterwards, he writes: 'I went to Bartholomew Fair, to walk up and down; and there, among other things, find my Lady Castlemaine at a puppet-play (Patient Chisel), and a street full of people expecting her coming out.' This infamous woman divided her affections between the king, Charles II, and Jacob Hall, the rope-dancer, who was a great favourite at the fair, and salaried by her ladyship. In 1668, Pepys again notes two visits he paid to the fair, in company with Lord Brouncker and others, to see 'The mare that tells money, and many things to admiration-and then the dancing of the ropes, and also the little stage-play, which is very ridiculous.' In 1699, Ned Ward notes in his Laudon Spy, a visit he paid to the fair, viewing it from a public-house near the Hospital Gate, under the influence of a pipe. 'The first objects, when we were seated at the window, that lay within our observation, were the quality of the fair, strutting round their balconies in their tinsel robes, and golden leather buskins, expressing such pride in their buffoonery stateliness, that I could but reasonably believe they were as much elevated with the thought of their fortnight's pageantry, as ever Alexander was with the thought of a new conquest; looking with great contempt on their split deal-thrones upon the admiring mobility gazing in the dirt at our ostentatious heroes, and their most supercilious doxies, who looked as awkward and ungainly in their gorgeous accoutrements, as an alderman's lady in her stiff-bodied gown upon a lord-mayor's festival.' One of the most famous of these great theartrical booths was that owned by Lee and Harper, tell represented in the above engraving, copied. from a carious general view of the fair, designed to form a fan-mount, and probably published about 1728.  Here one of the old favourite sacred dramas is being performed on the history of Judith and Holophernes, and both these characters parade the stage in front; the hero in the stage-dress of a Roman general; the heroine in that of a Versailles court-masque, with a feathered head-dress, a laced stomacher, and a hooped petticoat of crimson silk, with white rosettes in large triangles over its ample surface. A few of these Bartholomew-fair dramas found their way into print, the most remarkable of the series being the Siege of Troy, by Elkanah Settle, once the favourite court-poet of Charles II, and the rival of Dryden; ultimately a poor writer for Mrs. Mynn's booth, compelled in old age to roar in a dragon of his own invention, in a play founded on the tale of St. George. These dramas are curously indicative of popular tastes, filled with bombast interspersed with buffoonery, and gorgeous in dress and decoration. There is an anecdote on re-cord of the proprietress of this show refusing to pay 0ram, the scene-painter, for a splendid set of scenes he was en-gaged to paint, becasue he had used Dutch metal instead of leaf gold in their decoration. Settle's Siege of Troy is a good specimen of these productions, and we are told in the preface, is no ways inferior to any one opera yet seen in either of the royal theatres.' One of the gorgeous displays offered to the sightseers is thus described: The scene opens and discovers Paris and Helen, fronting the audience, riding in a triumphant chariot, drawn by two white elephants, mounted by two pages in embroidered livery. The side-wings are ten elephants more, bearing on their backs open castles, umbrayed with canopies of gold; the ten castles filled with ten persons risibly drest, the retinue of Paris; and on the elephants' necks ride ten Inure pages in the like rich dress. Beyond and over the chariot is seen a Vistoeik of the city of Troy, in the walls of which stand several trumpeters, seen behind and over the head of Paris, who sound at the opening of the scene.' Of course such magnificent people talk 'brave words,' like Ancient Pistol. Paris declares: Now when the tired world's long discords cease, We'll time our Trumps of War to Songs of Peace. Where Hector dragg'd in blood, I'll drive around The walls of Troy; with love and laurels crown'd. All this magniloquence is relieved by comic scenes between a cobbler (with the appropriate name of Bristles) and his wife, one 'Captain Tom,' and ' a numerous train of Trojan mob.' The regular actors, as we have before observed, were transplanted to the fair during its continuance, and some of them were protent proprietors and managers of the great theatrical booths. Penkethman, Mills, Booth, and Doggett were of the number. The great novelist, Henry Fielding, commenced career as part-proprietor of one of these booths, continuing for nine years in company with Hippisley, the favourite comedian, and others. It was at his booth, in 1733, that the famous actress, Mrs. Pritchard, made her great success, in an adaptation by Fielding, of Moliere's Cheats of Scapin.  The fan-mount, already described, furnishes us with another representation of a booth in the fair; and it will be perceived that they were solid erections of timber, walled and roofed with planks, and perfectly weather-proof. In this booth 'Faux's dexterity of hand' is displayed, as well as a famous posture-master,' whose evolutions are exhibited iii a picture outside the show. Faux was the Robert Hondin of his day, and is recorded to have died worth £10,000, which he had accumulated during his career. The Gentleman's Magazine for February 1731, tells us that the Algerine ambassadors visited him, and at their request he skewed them a view of Algiers, ' and raised up all apple-tree which bore ripe apples in less than a minute's time, which several of the company tasted of.' There was abundance of other shows to gratify the great British public; wild beasts, monsters, learned pigs, dwarfs, giants, et hoc genius Quite abounded. 'A prodigious monster' is advertised, 'with one head and two distinct bodies;' and 'An admirable work of nature, a woman having three breasts.' Then there was to be seen, 'A child alive, about a year and a half old, that has three legs.' It appears that nobility and even royalty patronised these sights, thus ' The tall Essex woman,' in the reign of George I, 'had the honour to show herself before their Royal Highnesses the Prince and Princess of Wales, and the rest of the royal family, last Bartholomew Fair.' A distinguished visitor is seen in our last engraving decorated with the ribbon and star of the Garter. The figure is by some supposed to represent the premier, Sir Robert Walpole, who was a frequent visitor to the fair; his attention is directed to Faux's booth by an attendant; but these figures may be intended to depict the Prince of Wales, who visited the fair in company with Rich, the manager and actor, who did duty as cicerone on the occasion. The licence and riot which characterised the proceedings in Smithfield, at last aroused the civic authorities, and after much rioting and many ineffectual attempts, the fair was again limited to three days' duration, by a resolution of the court of common council in 1708. The theatrical booths were still important features in the fair, and in 1715, we hear of ' one great playhouse erected for the king's players-the booth is the largest that ever was built.' During the run of the Beggar's Opera, it was reproduced by Rayner and Pullen's company at the fair. In 1728, Lee and Harper produced a ballad-opera on the adventures of Jack Sheppard, and in 1730, another devoted to the popular hero-Robin Hood. Dramatic entertainments ultimately declined, but monstrosities never failed, and gratified the Londoners to the last day of the existence of the fair. Pig faced ladies were advertised, if not seen; but learned pigs were never wanting, who could do sums in arithmetic, tell fortunes by cards, &c. Wild-beast shows ended in being the principal attraction, though they were the most expensive exhibitions in the fair; a shilling being charged for admission. The mayor endeavoured to stem the irregularities of the fair in 1769, by appointing seventy-two officers to keep the peace and prevent gambling, as well as to hinder the performance of plays and puppet-shows. In 1776, the mayor refused per-mission to erect booths at all, which occasioned great rioting. Some years before this, the deputy-marshal lost his life in endeavouring to enforce order in the fair. The most dangerous rioters were a body of blackguards, who termed themselves ' Lady Holland's Mob,' and assembled to proclaim the fair after their own fashion, the night before the mayor did so. Hone says, 'the year 1822 was the last year wherein they appeared in any alarming force, and then the inmates of the houses they assailed, or before which they paraded, were aroused and kept in terror by their violence. In Skinner Street especially, they rioted undisturbed until between three and four in the morning: at one period that morning, their number was not less than five thousand, but it varied as parties went off or came in to and from the assault of other places. Their force was so overwhelming, that the patrol and watchmen feared to interfere, and the riot continued till they had exhausted their fury.' The last royal visit to the fair took place in 1778, when the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester rode through it. Flockton's puppets were at this time a great attraction. Mr. Lane, 'his majesty's conjuror,' and Mr. Robinson, 'conjuror to the queen,' divided the attention of amateurs of their art. Mite's 'Grand collection of wild beasts' were brought from Exeter Change; 'The famous ram with six legs,' The unicorn ram,' 'The performing serpents,' and other wonders in natural history, also invited visitors; as well as ' A surprising large fish,' affirmed to have 'had in her belly, when found, one thousand seven hundred mackerel.'  When Hone visited the fair in 1825, he saw, in a penny-show, the mermaid which had been exhibited about a year before in Piccadilly, at the charge of half-a-crown each person. This imposture was a hideous combination of a dried monkey's head and body, and the tail of a fish, believed to have been manufactured on the coast of China, and exhibited as the product of the seas there. George Cruikshank has preserved its features, and we are tempted to reproduce his spirited etching. 'A mare with seven feet' was a lusus naturae also then exhibited, giants and dwarfs of course abounded, as they ever do at fairs! Atkin's and Wombwell's menageries were the great shows of the fair in its expiring glory. They still charged the high price of one shilling admission. Richardson's theatre was the only successful rival in price and popularity-here was a charge of boxes 2s., pit ls., gallery 6d.; but the deluded exclusives who paid for box or pit seats, found on entering only a steep row of planks elevated above each other in front of the stage, without any distinction of parties, or anything to prevent those on the top row from falling between the supports to the bottom!  Here, in the course of a quarter of an hour, a melodrama, with a ghost and several murders-a comic song by way of interlude, and a pantomime-were all got through to admiring and crowded audiences; by which the manager died rich. Richardson was also proprietor of another 'show' in the fair; this was 'The beautiful spotted negro boy,' a child whose skin was naturally mottled with black, and whose form has been carefully delineated in a good engraving, here copied. He was a child of amiable manners, much attached to Richardson, who behaved with great kindness toward him; consequently both of them were in high favour with the public. He was the last of the great natural curiosities exhibited there, for the fair gradually dwindled to death, opposed by the civic authorities and all decent people. It was at one time resolved to refuse all permission to remove stones from pavement or roadway, for the erection of booths; but the showmen evaded the restriction by sticking their poles in large and heavy tubs of earth. Then high ground-rents were fixed, which proved more effectual; and in 1850, when the mayor went as usual to Clothfair-gate to proclaim the opening of the fair, he found nothing awaiting to make it worth that trouble. No mayor went after, and until 1855, the year of its suppression, the proclamation was read by a deputy. |