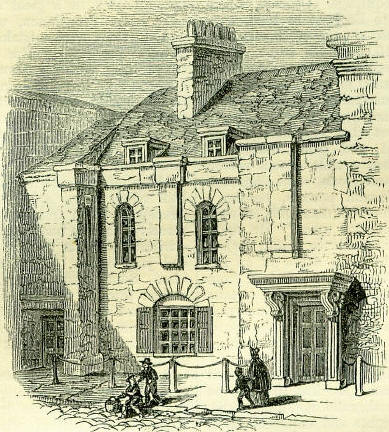

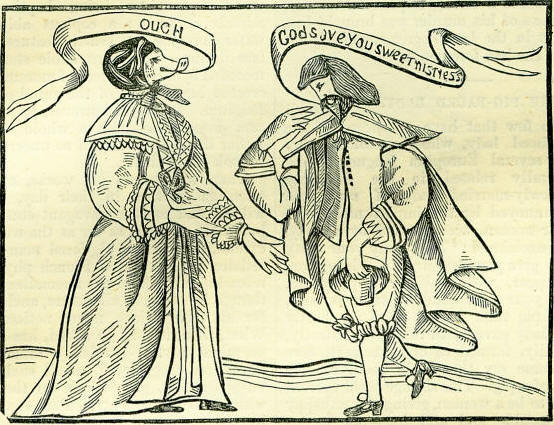

23rd AugustBorn: Louis XVI, king of France, 1754, Versailles; Sir Astley Cooper, eminent surgeon, 1768, Brooks, Norfolk; William Frederick I, king of the Netherlands, 1772; Friedrich Tiedemann, physiologist, 1781, Cassel; Frank Stone, artist, 1800, Manchester. Died: Flavius Stilicho, great Roman general, beheaded at Ravenna, 408; Sir William Wallace, Scottish hero, 1305, executed at Smithfield, London; William Warham, archbishop of Canterbury, 1532; George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, assassinated at Portsmouth, 1628; Jacques Vergier, poet and tale-writer, assassinated at Paris, 1720. Feast Day: Saints Claudius, Asterius, Neon, Domnina, and Theonilla, martyrs, 285. St. Theonas, archbishop of Alexandria, 300. St. Justinian, hermit and martyr, about 529. St. Apollinaris Sidonius, confessor, bishop of Clermont, 482. St. Eugenius, bishop in Ireland, 618. St. Philip Beniti, confessor, 1285. WILLIAM WALLACEEdward I of England having by craft and violence taken military possession of Scotland; the chief nobles of the land having submitted to him; it was left to a young gentleman of Renfrew-shire, the celebrated William Wallace, to stand forth in defence of the expiring liberties of his country. He was, in some respects, well fitted to be a guerilla chief, being of lofty stature and hardy frame, patient of fatigue and hardship, frank in his manners, and liberal to his associates, while at the same time of sound judgment and a lover of truth and justice. The natural ascendancy of such qualities quickly put him at the head of large, though irregular forces, and he won an important victory at Stirling over some of Edward's principal officers (Sept. 11th, 1297). A month later, he and Andrew of Moray are found, under the title of Daces exercitus regni Scotia, administering in national affairs-sending two eminent merchants to negotiate with the two Muse towns of Lubeck and Hamburg. Next year, in a public document, Wallace appears by himself under the title of Custos regni Scotia. During this interval of authority, acting upon a cruel though perhaps unavoidable policy, he executed a complete devastation of the three northern counties of England, leaving them a mere wilderness. Edward led an army against him in person, and gaining a victory over him at Falkirk (July 22nd, 1298), dispersed his forces, and put an end to his power. While most of the considerable men submitted to the English monarch, Wallace proceeded to France, to make interest with its king, Philip the Fair, in behalf of Scotland. Philip gave him some encouragement, and furnished. him (this fact has only of late become known) with a letter of recommendation to the pope. Afterwards, being glad to make peace with Edward for the sake of the recovery of his authority over Flanders, Philip entered into an agreement to deliver up the ex-governor of Scotland to his enemy. The fact, however, was not accomplished, and Wallace was able to return to his own country. Being there betrayed by Sir John Monteith into the hands of the English, he was led to London; subjected to a mock-trial at Westminster, as if he had been a traitor to his sovereign Edward I; and, on the 23rd of August 1305, put to a cruel death on Smithfield. The Scottish people have ever since cherished the memory of Wallace as the assertor of the liberties of their country-their great and ill-requited chief. What Tell is to the Swiss, and Washington to the Americans, Wallace is to them. It is true that he had little or no mercy for the English who fell into his hands, and that he ravaged the north of England. If, however, the English put themselves into the position of robbers and oppressors in a country which did not belong to them, they were scarcely entitled to much mercy; and, certainly, at a time so rude as the close of the thirteenth century, they were not very likely to receive it. GEORGE VILLIERS, FIRST DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM'Princes and lords are but the breath of kings.' Seldom has this sentiment been more strikingly exemplified than in the case of this nobleman. His rapid and unmerited advancement, effected solely by a sovereign's capricious will, stands almost, if not entirely, unparalleled in history. His father was Sir George Villiers of Brokesby, in Leicester-shire, who possessed but a moderate property, was twice married, and had nine children. The duke-his father's fourth son-was by his second wife, Mary, daughter of Anthony Beaumont of Glenfield, Leicestershire, and was born on the 20th of August 1592. He was educated at home in fencing, riding, dancing, and other gentlemanly accomplishments of the period, and, at the age of eighteen, went to France for his further improvement. After travelling there for about three years, he returned to England in 1613, and obtained an appointment at court as cup-bearer to King James I, 'who of all wise men living,' says Clarendon, 'was the most delighted and taken with handsome persons in fine clothes.' Young Villiers was remarkable for the beauty of his person, the gracefulness of his air, the elegance of his dress, the suavity and sprightliness of his conversation. The king was delighted with him, and, in token of his admiration, gave him the familiar name of Steenie, in allusion to a beautiful portrait in Whitehall representing St. Stephen, the proto-martyr. Honours now fell rapidly upon him. Here is a glance at his progress: 1615 - Knighted, and made one of the Gentlemen of the Bedchamber. 1616 - Master of the Horse; Knight of the Garter; Baron of Whaddon; Viscount Villiers. 1617 - Earl of Buckingham; Marquis of Buckingham; Lord High Admiral; Chief-justice in Eyre, south of Trent; Master of the King's Bench; High Steward of Westminster; Constable of Windsor Castle. 1623 - Earl of Coventry; Duke of Buckingham; Warden of the Cinque Ports; Steward of the Manor of Hampton Court. Thus, in the course of ten years, King James raised his favourite from a poor cup-bearer to the highest title a sovereign has to bestow. Nor did he lavish on him merely titles and lucrative appointments; he enriched him with magnificent grants from the royal domains; thus placing him not only among the highest, but among the wealthiest, noblemen in the land. The royal lordship of Whaddon alone, from which the duke derived his first title, contained four thousand acres and a chase sufficient for a thousand deer. To gratify his favourite still more, the king extended his patronage to his whole family. His mother was, in 1618, created Countess of Buckingham; his elder brother, John, was made Baron Villiers and Viscount Purbeck; his younger brother, Christopher, was, in 1623, created Earl of Anglesey and Baron of Daventry; his half-brother, William, was, in 1619, created a baronet; and his other half-brother, Edward, was knighted in 1616, and in 1622 was appointed president of Munster, in Ireland-a lucrative post of great honour, which had previously always been held by a nobleman. The duke's influence at court was not diminished by the death of King James, for he had become no less a favourite with the succeeding monarch, Charles I; so much so, indeed, that Clarendon, who, on the whole, speaks favourably of Villiers, asserts that 'all preferments in church and state were given by him; all his kindred and friends promoted to the degree in honour, or riches, or offices that he thought fit; and all his enemies and enviers discountenanced as he appointed.' To him the church, the realm, their powers consign; Through him the rays of regal bounty shine; Turned by his nod the stream of honour flows; His smile alone security bestows: Still to new heights his restless wishes tower, Claim leads to claim, and power advances power, Till conquest, unresisted, ceased to please, And rights submitted left him none to seize. Raised to this pinnacle of power, the duke displayed a presumption perfectly intolerable. One or two instances will amply illustrate this. When sent to France, by Charles I, to bring over Henrietta, his betrothed wife, the queen of France, being indisposed, was confined to her bed, and the duke was permitted to have an interview with her in her chamber. But, instead of approaching her as an ambassador, he had 'the insolence to converse with her as a lover!' The Marchioness of Sencey, the queen's lady of honour, who was present, gave the duke a severe reproof, saying: 'Sir, you must learn to be silent; it is not thus we address the queen of France!' Afterwards, when the duke would have gone on another embassy to the French court, it was signified to him, that for reasons well known to himself, his presence would not be agreeable to the king of France. The duke exclaimed: 'He would go and see the queen in spite of the French court!' 'And to this pretty affair,' remarks our authority, 'is to be ascribed the war between the two nations!' His insolence to Henrietta herself, when queen of England, was even more audacious. 'One day,' says Clarendon, 'when he unjustly apprehended that the queen had shewn some disrespect to his mother, in not going to her lodging at an hour she had intended to go, and was hindered by mere accident, he came into her chamber in much passion, and after some expostulations rude enough, he told her, she should repent it. Her majesty answering with some quickness, he thereupon replied insolently to her-that there had been queens in England who had lost their heads!' The duke had a strong passion for magnificence. In 1617, only three or four years after his first entrance at court, he gave a most sumptuous entertainment on his being created a marquis. The banquet, which was held in Whitehall, was served up in the French fashion, under the auspices of Sir Thomas Edmondes, who had recently returned from France. 'You may judge,' writes an eye-witness of the feast, 'by this scantling, that there were said to be seventeen dozens of pheasants, and twelve partridges in a dish; throughout which, methinks, were more spoil than largesse. In spite of many presents,' the feast cost six hundred pounds. Buckingham was equally excessive in the splendour of his equipage. Coaches, which were first introduced into England in 1580, were at first only used with a pair of horses, but Buckingham, about 1619, had his coach drawn by six horses, which was, says Wilson, 'wondered at as a novelty, and imputed to him as a mastering pride.' He was also remarkable for his extravagance in dress. 'He had twenty-seven suits of clothes made, the richest that embroidery, lace, silk, velvet, silver, gold, and gems could contribute; one of which was a white uncut velvet, set all over, both suit and cloak, with diamonds valued at fourscore thousand pounds, besides a great feather stuck all over with diamonds, as were also his sword, girdle, hat, and spurs.' He could also afford to have his diamonds so loosely tacked on, that when he chose to shake a few off on the ground, he obtained all the fame he desired from the pickers-up; for he never condescended to take back those which he had dropped. In the masques and banquets with which he entertained the court, he is said to have usually expended for the evening from one to five thousand pounds. The consequences of the duke's rise were most disastrous to the kingdom. He had little or no genuine patriotism, and either did not understand, or would not heed, the rights and requirements of his fellow-subjects. Indebted for his own position to mere favouritism, he, who was now sovereign all but in name, dispensed posts of importance and responsibility on the same baneful principles. Discontent became general. The ancient peers were indignant at having a man thrust over their heads with little to recommend him but his personal appearance and demeanour. The House of Commons were still more indignant at having measures, which they knew to be ruinous to the country, forced on them by a minister who, to gain his own ends, would not hesitate to hazard. the honour and prosperity of the whole nation. This was especially manifested in two of his proceedings. From a private pique of his own, he involved his country first in a war with Spain, and. afterwards with France, both of which wars brought discredit and perplexity on England. The House of Commons prepared a bill of impeachment against him, containing no less than sixteen charges; and the king only warded off the blow by suddenly dissolving parliament. This, as Clarendon admits, was not only irregular but impolitic. The country became exasperated, and Buckingham's life was known to be in danger. 'Some of his friends,' says Sir Symonds d'Ewes, 'had advised him how generally he was hated in England, and how needful it would be for his greater safety to wear some coat-of-mail, or some secret defensive armour, but the duke, sighing, said: 'It needs not-there are no Roman spirits left! 'Warnings and threatenings were alike unheeded, and the duke proceeded to head a new expedition, which he had planned to relieve the Protestants of Rochelle. Having engaged a house at Portsmouth, to superintend the embarkation of his forces, he passed the night there with the duchess, and others of his family, and on Saturday, August 23, 1628, 'he did rise up,' says Howell, 'in a well-disposed humour out of his bed, and cut a caper or two, and being ready, and having been under the barber's hands, he went to break-fast, attended by a great company,' among whom were some Frenchmen, whose eager tones and gesticulations were mistaken by some of the bystanders for anger. The duke, being in private conversation with Sir Thomas Fryar, was stooping down to take leave of him, when he was suddenly struck over his shoulder with a knife, which penetrated his heart. He exclaimed 'The villain has killed me!' and at the same moment pulling out the knife, which had been left in his breast, he fell down dead. Many of the attendants at first thought he had fallen from apoplexy, but, on seeing the effusion of blood from his breast and mouth, they perceived that he had been assassinated, and at once attributed the act to one of the Frenchmen who had just before been so eagerly conversing with him. Some hasty spirits, drawing their swords, rushed towards the Frenchmen, to take summary vengeance on them all, and were restrained with so much difficulty, that, according to Clarendon, 'it was a kind of a miracle that the Frenchmen were not all killed in that instant.' The Duchess of Buckingham and the Countess of Anglesey, having entered a gallery looking into the hall, beheld the lifeless body of the duke. 'Ah, poor ladies!' writes Lord Carlton, who was present at the murder, 'such were their screechings, tears, and distractions, that I never in my life heard the like before, and hope never to hear the like again.' Amid tins distracting scene, a man's hat was found near the door where the murder was committed, and in the crown of it was sewn a written paper containing these words: That man is cowardly base, and deserveth not the name of a gentleman or souldier, that is not willinge to sacrifice his life for the honor of his God, his Kinge, and his Countrie. Lett no man Commend me for doeinge of it, but rather discommend themselves as the cause of it, for if God had not taken away or hartes for or sinnes, he would not have gone so lunge unpunished. Jo: felton. Felton, the owner of the hat, was found, says Lord Carlton, ' standing in the kitchen of the same house, and after inquiry made by a multitude of captains and gentlemen, then pressing into the house and court, and crying out amain, ' Where is the villain? Where is the butcher?' he most audaciously and resolutely drawing forth his sword, came out, and went amongst them, saying boldly: I am the man; here I am I' Upon which divers drew upon him, with an intent to have then despatched him; but Sir Thomas Morton, myself, and some others used such means (though with much trouble and difficulty) that we drew him out of their hands,' and he was conveyed by a guard of musketeers to the governor's house. John Felton, who was a younger son of a Suffolk gentleman,' was by nature,' says Sir Henry Wotton, 'of a deep melancholy, silent, and gloomy constitution, but bred in the active way of a soldier, and thereby raised to the place of lieutenant to a foot company, in the regiment of Sir James Ramsay. On being questioned as to his motives for committing the murder, he replied, that he was dissatisfied, partly because his pay was in arrear, and partly because the duke had promoted a junior officer over him, but that his chief motive was to ' do his country a great good service;' and that he ' verily thought, in his soul and con-science, the re-monstrance of the parliament was a sufficient warrant for what he did upon the duke's person.' He under-went several examinations, always asserting that he had no accomplices; and when the Earl of Dorset threatened, in the king's name, to examine him on the rack; he said: I do again affirm, upon my salvation, that my purpose was known to no man living; and more than I have said before, I cannot. But if it be his majesty's pleasure, I am ready to suffer whatever his majesty will have inflicted upon me. Yet this I must tell you by the way, that if I be put upon the rack, I will accuse you, my Lord Dorset, and none but yourself. This bold resolve astounded the examiners. They hesitated, and consulted the judges, who unanimously replied, that 'torture was not justifiable according to the law of England.' So that by this firmness Felton did, indeed, 'great good service to his country.' He forced from the judges an avowal of a law which condemned all their former practice. He was imbued with fanaticism, had a revengeful spirit, and gloried in manifesting it. Having once been offended by a gentleman, he cut off a piece of his own finger, and enclosing it with a challenge, sent it to him, to shew how little he heeded pain provided he could have vengeance. He continued in prison till November, passing the time in deep penitence and devotion, and was executed at Tyburn towards the end of the month, and was afterwards hung in chains at Portsmouth. The Duke of Buckingham, who had married Catherine, daughter and sole heir of Francis, Earl of Rutland, was thirty-six years old at his death. His body was buried, by command of the king, in Westminster Abbey, and a sumptuous monument was erected within the communion rails of the church at Portsmouth; but it has recently been removed into the north aisle of the chancel. The house in which Buckingham was assassinated still exists, with but slight modern alterations, being marked No. 10 in the High Street of Ports-mouth. The kitchen to which Felton retired is a distinct building at the further end, according to our view.  The duke's murder is said to have been preceded by many supernatural warnings, the most curious of which was the reputed appearance of his father's ghost. The story, which is gravely and circumstantially related by Clarendon, is long and tedious, but the substance of it is as follows: About six months before the duke's murder, as one Mr. Towse, an officer of the king's wardrobe, was lying awake in his bed at Windsor, about midnight there appeared at his bedside, ' a man of a very venerable aspect, who drew the curtains of his bed, and fixing his eyes upon him, asked him, if he knew him. The poor man, half-dead with fear,' on being asked the second time, said, he thought he was Sir George Villiers, the father of the Duke of Buckingham. The ghost told him he was right; and then charged him to go to the duke, and assure him that if he did not endeavour to ingratiate him-self with the people, and abate their malice against him, he would not be suffered to live long. The next morning, Mr. Towse tried to persuade himself that his vision had been only a dream, and dismissed the subject from his mind. But at night the same apparition visited him, and, with an angry countenance, reproached him for not having attended to his charge, and told him he should have no peace till he did so. Mr. Towse promised to obey; but in the morning, not at all relishing the commission, he again treated it as a mere dream. On the third night, the same apparition again stood at his bed, and, with 'a terrible countenance, bitterly reproached him for not performing what he had promised to do.' Mr. Towse now ventured to address the spectre, and assure him that he would willingly execute his command, but that he knew not how to gain access to the duke, or if he did, how to convince him that the vision was anything more than the delusion of a distempered mind. The ghost replied, that he should have no rest till he had fulfilled his commission; that access to the duke was easy; and that he would tell him two or three particulars, in strict secrecy, to repeat to him, which would at once insure confidence in all he should say, 'and so repeating his threats, he left him. Mr. Towse obtained an interview with the duke, who, on being told ' the secret particulars,' changed colour, and swore no one could have come to that knowledge except by the devil; for that those particulars were known only to himself, and to one person more, who he was sure would never speak of it.' After this interview, the duke appeared unusually thoughtful, and in the course of the day he had a long conference with his mother. But he made no change in his conduct; nor is it known whether or not he gave any credit to the story of the apparition, though it is supposed that his repetition of it to his mother, made a strong impression on her, for when the news of his murder was brought her, ' she seemed not in the least degree surprised, but received it as if she had foreseen it.' THE PIG-FACED LADYThere can be few that have not heard of the celebrated pig faced lady, whose mythical story is common to several European languages, and is most generally related in the following manner: A newly-married lady of rank and fashion, being annoyed by the importunities of a wretched beggar-woman, accompanied by a dirty, squalling child, exclaimed: 'Take away your nasty pig, I shall not give you anything!' Whereupon, the enraged beggar, with a bitter imprecation, retorted: 'May your own child, when it is born, he more like a pig than mine!' And so, shortly afterwards, the lady gave birth to a girl, perfectly, indeed beautifully, formed in every respect, save that its face, some say the whole head, exactly resembled that of a pig. This strange child thrived apace, and grew to be a woman, giving the unhappy parents great trouble and affliction-not by its disgusting features alone, but by its hoggish manners in general, much easier to be imagined than minutely described. The fond and wealthy parents, however, paid every attention to this hideous creature, their only child. Its voracious and indelicate appetite was appeased by food, placed in a silver trough. To the waiting-maid, who attended on the creature, risking the savage snaps of its beastly jaws, and enduring the horrid grunts and squeaks of its discordant voice, a small fortune had to be paid as annual wages, yet seldom could a person be obtained to fill the disagreeable situation longer than a month. A still greater perplexity ever troubled the wealthy parents, namely, what would become of the unfortunate creature after their decease? Counsel learned in the law were consulted, and it was determined that she should be married, the father, besides giving a magnificent dowry in hand, settling a handsome annuity on the happy husband for as long as she should live. But experience proving, that after the first introduction, the boldest fortune-hunters declined any further acquaintance, another course was suggested. This was to found a hospital, the trustees of which were bound to protect and cherish the pig-faced damsel, until her death relieved them from the umpleasing guardianship. And thus it is that, after long and careful research on the printed and legendary histories of pig-faced ladies, the writer has always found them wanting either a husband or a waiting maid, or connected with the foundation of a hospital. But as there are exceptions to all general rules, so there is an exceptional story of a pig faced lady; according to which, it appears that a gentleman, whose religious ideas were greatly confused by the many jarring sects dining the Commonwealth, ended his perplexity by adopting the Jewish faith. And the first child born to him, after his change of religion, was a pig faced girl! Years passed, the child grew to womanhood before the wretched father perceived that her hideous countenance was a divine punishment, inflicted on him for his grievous apostasy. Then a holy priest reconverted the father, and on the daughter being baptized, a glorious miracle occurred; a copious ablution of holy-water changing the beastly features to the human face divine. This remarkable story is said to be recorded by a choice piece of monumental sculpture, erected in some one of the grand old cathedrals in Belgium. It might, however, be better to take it cum grano salis-with a whole bushel thereof-rather than go so far, on so uncertain a direction, to look for evidence. There are several old works, considered sound scientific treatises in their day, filled with the wildest and most extravagant stories of monsters, but none of them, as far as the writer's researches extend, mentions a pig faced man or woman. St. Hilaire, the celebrated French physiologist, in his remarkable work on the anomalies of organisation, though he ransacks all nature, ancient and modern, for his illustrations, never notices such a being. What, then, it may be asked, has caused this very prevalent myth? Probably some unhappy malformation, exaggerated, as all such things are, by vulgar report, gave origin to the absurd story; which was subsequently enlarged and disseminated by the agency of lying catch-penny publications of the chap-book kind. There was exhibited in London, a few years ago, a person who, at an earlier period, might readily have passed for a pig faced lady, though the lower part of her countenance resembled that of a dog more than a pig. This unfortunate creature, named Julia Pastorana, ' was said to be of Spanish-American birth. After being exhibited in London, she was taken to the continent, where she died; and such is the indecent cupidity of showmen, so great is the morbid curiosity of sight-seers, that her embalmed remains were re-exhibited in the metropolis during the last year! The earliest printed account of a pig-faced lady that the writer has met with, was published at London in 1641, and entitled A Certain Relation of the Hog-faced Gentlewoman. From this veracious production, we learn that her name was Tanakin Skinker, and she was born at Wirkham, on the Rhine, in 1618. As might be expected, in a contemporary Dutch work, which is either a translation or the original of the English one, she is said to have been born at Windsor on the Thames. Miss Skinker is described as having 'all the limbs and lineaments of her body well featured and proportioned, only her face, which is the ornament and beauty of all the rest, has the nose of a hog or swine, which is not only a stain and blemish, but a deformed ugliness, making all the rest loathsome, contemptible, and odious to all that look upon her.' Her language, we are further informed, is only 'the hoggish Dutch ough, ough! or the French owee, owee!' Forty thousand pounds, we are told, was the sum offered to the man who would consent to marry her, and the author says: ' This was a bait sufficient to make every fish bite at, for no sooner was this publicly divulged, but there came suitors of all sorts, every one in hope to carry away the great prize, for it was not the person but the prize they aimed at.' Gallants, we are told, came from Italy, France, Scotland, and England-were there no Irish fortune-hunters in those days?-but all ultimately refused to marry her.  The accompanying illustration is a facsimile of a wood-cut on the title-page of the work, representing a gallant politely addressing her with a 'God save you, sweet mistress,' while she replies only with the characteristic ' Ough!' Unlike some other pig-faced ladies, Miss Skinker always dressed well, and was 'courteous and kind in her way to all.' And the pamphlet ends by stating, that she has come to look for a husband in London, but whether she resides at Blackfriars or Covent Garden, the writer will 'say little,' lest the multitude of people who would flock to see her might, in their eagerness, pull the house down in which she resides. In the earlier part of this century, there was a kind of publication in vogue, somewhat resembling the more ancient broadside, but better printed, and adorned with a rather pretentious coloured engraving. One of those, published by Fairborn in 1815, and sold for a shilling, gives a portrait of the pi faced lady, her silver trough placed on a table beside her. In the accompanying letter-press, we are informed that she was then twenty years of age, lived in Manchester Square, had been born in Ireland, of a high and wealthy family, and on her life and issue by marriage a very large property depended. 'This prodigy of nature,' says the author, 'is the general topic of conversation in the metropolis. In almost every company you join, the pig-faced lady is introduced, and her existence is firmly believed in by thousands, particularly those in the west end of the town. Her person is most delicately formed, and of the greatest symmetry; her hands and arms are delicately modelled in the happiest mould of nature; and the carriage of her body indicative of superior birth. Her manners are, in general, simple and unoffending; but when she is in want of food, she articulates, certainly, something like the sound of pigs when eating, and which, to those who are not acquainted with her, may perhaps be a little disagreeable.' She seems, however, to have been disagreeable enough to the servant who attended upon her and slept with her; for this attendant, though receiving one thousand pounds per annum, as wages, left the situation, and gave the foregoing particulars to the publisher. And there can be little doubt that this absurd publication caused a poor simpleton to pay for the following advertisement, which appeared in the Times of Thursday, the 9th of February 1815: FOR THE ATTENTION OF GENTLEMEN AND LADIES.-A young gentlewoman having heard of an advertisement for a person to undertake the care of a lady, who is heavily afflicted in the face, whose friends have offered a handsome income yearly, and a premium for residing with her for seven years, would do all in her power to render her life most comfortable; an undeniable character can be obtained from a respectable circle of friends; an answer to this advertisement is requested, as the advertiser will keep herself disengaged. Address, post paid, to X. Y., at Mr. Ford's, Baker, 12 Judd. Street, Brunswick Square. Another simpleton, probably misled in the same manner, but aspiring to a nearer connection with the pig-faced lady, thus advertised in the Morning Herald of February 16, 1815: SECRECY.-A single gentleman, aged thirty-one, of a respectable family, and in whom the utmost confidence may be reposed, is desirous of explaining his mind to the friends of a person who has a misfortune in her face, but is prevented for want of an introduction. Being perfectly aware of the principal particulars, and understanding that a final settlement would be preferred to. a temporary one, presumes he would be found to answer the full extent of their wishes. His intentions are sincere, honourable, and firmly resolved. References of great respectability can be given. Address to M. D., at -Mr. Spencer's, 22 Great Ormond Street, Queen's Square. For oral relations of the pig faced lady, we must go to Dublin. If we make inquiries there respecting her, we shall be shewn the hospital that was founded on her account. We will be told that her picture and silver trough are to be seen in the building, and that she was christened Grisly, on account of her hideous appearance. Any further doubts, after receiving this information, will be considered as insults to common sense. Now, the history of Steevens's Hospital, the institution referred to, is simply this: In 1710, Dr. Steevens, a benevolent physician, bequeathed his real estate, producing £650 per annum, to his only sister, Grizelda, during her life; and, after her death, vested it in trustees for the erection and endowment of a hospital. Miss Steevens, being a lady of active benevolence-a very unusual character in those days, though happily not an uncommon one now-determined to build the hospital in her lifetime. Devoting £450 of her income to this purpose, she collected subscriptions and donations, and by dint of unceasing exertion, succeeded in a few years in opening a part of the building, equal to the accommodation of forty patients. Whether it was the uncommon name of Grizelda, or the uncommon benevolence of this lady, that gave rise to the vulgar notion respecting her face, will probably be never satisfactorily explained. But her portrait hangs in the library of the hospital, proving her to have been a very pleasant looking lady, with a peculiarly benevolent cast of countenance. A lady, to whom the writer applied for information, thus writes from Dublin: 'The idea that Miss Steevens was a pig-faced lady still prevails among the vulgar; when I was young, everybody believed it. When this century was in its teens, it was customary, in genteel society, for parties to be made up to go to the hospital, to see the silver trough and pig faced picture. The matron, or housekeeper, that shewed the establishment, never denied the existence of those curiosities, but always alleged she could not shew them, implying, by her mode of saying it, that she dared not, that to do so would be contrary to the stringent orders she had received. The housekeeper, no doubt, obtained many shillings and tenpennies by this equivocating mode of keeping up the delusion. Besides, many persons who had gone to the hospital to see the trough and picture, did not like to acknowledge that they had not seen them. I can form no opinion of the origin of the myth, but can give you another instance of its dissemination. Old Mr. B., whom you may just recollect, had an enormous silver punch-bowl, much bruised and battered by long service in the cause of Bacchus. The crest of a former proprietor, representing a boar's head, was engraved upon it; and my poor aunt, not inappropriately, considering the purposes for which the bowl was used and the scenes it led to, used to call it the pig trough. Every child and servant in the house believed that it was one of the pig faced lady's troughs; and the crest, her correct likeness. The servants always shewed it as a great curiosity to their kitchen-visitors, who firmly believed the stupid story. And I have always found, in the course of a long life, that ignorant minds accept fiction as readily as they reject truth.' The pig faced lady is not unfrequently exhibited, in travelling caravans, by showmen at fairs, country-wakes, races, and places of general resort. The lady is represented by a bear, having its head carefully shaved, and adorned with cap, 'bonnet, ringlets, flowers, &c. The animal is securely tied in an upright position, into a large arm-chair, the cords being concealed by the shawl, gown, and other parts of the lady's dress. |