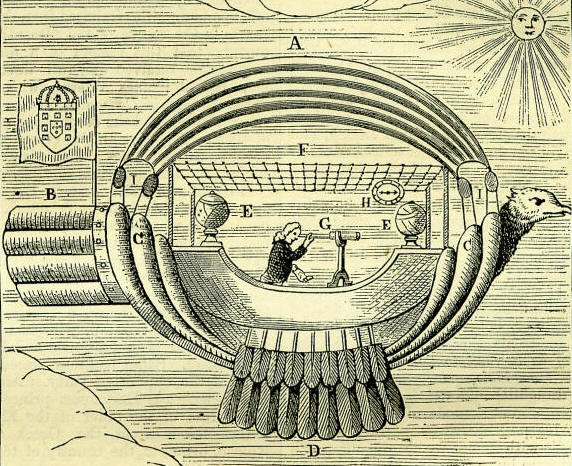

20th DecemberBorn: John Wilson Croker, reviewer and miscellaneous writer, 1780, Galway. Died: Ignatius, bishop of Antioch, martyred at Rome, 107 A.D.; Bernard de Montfaucon, French antiquary, 1741; Louis the Dauphin, father of Louis XVI, 1765; Thomas Hill, patron of literary men, and prototype of Paul Pry, 1840, Adelphi, London. Feast Day: St. Philogonius, bishop of Antioch, confessor, 322. St. Paul of Latrus, or Latra, hermit, 956. THE SUPPRESSION OF STAGE-PLAYSOn December 20, 1649, 'some stage-players in St. John Street were apprehended by troopers, their clothes taken away, and themselves carried to prison.' Whitelocke's Memorials. When England was torn by civil strife, the drama had a hard struggle for existence. Its best supporters had more serious matters to attend to, and while its friends were scattered far and wide, its foes were in authority, and wielded their newly-won power without mercy. When the civil warbroke out, one of the first acts of parliament was the issuing, in September 1642, of the following: Ordinance of the Lords and Commons concerning Stage-plays. Whereas the distressed estate of Ireland, steeped in her own blood, and the distracted estate of England, threatened with a cloud of blood by a civil war, call for all possible means to appease and avert the wrath of God appearing in these judgments; amongst which fasting and prayer, having been often tried to be very effectual, have been lately, and are still, enjoined; and whereas public sports do not well agree with public calamities, nor public stage-plays with the seasons of humiliation, this being an exercise of sad and pious solemnity, and the other being spectacles of pleasure too commonly expressing lascivious mirth and levity; it is therefore thought fit, and ordered by the Lords and Commons in this Parliament assembled, that while these sad causes and set times of humiliation do continue, public stage-plays shall cease and be forborne. Instead of which are recommended to the people of this land the profitable and seasonable consideration of repentance, reconciliation, and peace with God, which probably will produce outward peace and prosperity, and bring again times of joy and gladness to these nations. It was not to be expected that this unwelcome ordinance would be submitted to in silence. The Actors' Remonstrance soon appeared, complaining of the inconsistency of parliament in closing well-governed theatres, used only by the best of the nobility and gentry, while it permitted the bear-gardens to remain unmolested, patronised, as they were, by boisterous butchers, cutting cobblers, hard-handed masons, and the like riotous disturbers of the public peace; and gave uncontrolled allowance to puppet-shows. After defending the play-houses against sundry charges of their assailants, the pamphleteer promises, on behalf of the poor disrespected players, that if they are re-invested in their houses, they will not admit any female whatsoever unless accompanied by her husband or some near relative; that they will reform the abuses in tobacco, and allow none to be sold, even in the threepenny galleries, except the pure Spanish leaf; that all ribaldry shall be expelled the stage; and for the actors: we will so demean ourselves as none shall esteem us of the ungodly, or have cause to repine at our actions or interludes; we will not entertain any comedian that shall speak his part in a tone as if he did it in derision of some of the pious, but reform all our disorders and amend all our amisses. The author of Certain Propositions offered to the Consideration of the Honourable Houses of Parliament, advises that (as there must necessarily be amusements at Christmas, whether parliament likes it or not) the authorities should declare they merely intended to reform, and not abolish the actor's calling, and to that end confine the plots of plays to scriptural subjects. He is evidently a royalist, and satirically suggests: Joseph and his brethren would make the ladies weep; that of David and his troubles would do pretty well for the present; and, doubtless, Susannah and the elders would be a scene that would take above any that were ever yet presented. It would not be amiss, too, if, instead of the music that plays between the acts, there were only a psalm sung for distinction sake. This might be easily brought to pass, if either the court playwriters be commanded to read the Scriptures, or the city Scripture-readers be commanded to write plays. One half-serious argument used in favour of re-opening the theatres was that, by so doing, the ranks of the royal army would be materially weakened. Most of the leading actors of the clay had, in fact, exchanged their stage-foils for weapons of a deadlier sort. Prince Rupert's regiment had in its ranks three of the most popular representatives of feminine parts-Burt being a cornet, Hart a lieutenant, and Shatterel quartermaster. Mohun became captain in another regiment; and Allen of the Cockpit was quartermaster-general at Oxford. Other players contrived, spite of the law, to eke out a precarious living by practising their profession by stealth. In 1644, the sheriffs dispersed an audience assembled at the Salisbury Court Theatre to witness Beaumont and Fletcher's King and No King; but the poor players still found such encouragement in defying the law, that a second ordinance was issued, instructing the civic authorities to seize all actors found plying their trade, and commit them to the common jail, to be sent to the sessions, and punished as rogues. This proving inefficacious, in 1647 a more stringent act was passed, by which it was enacted 'that all stage-players, and players of interludes, and common plays are, and shall be, taken for rogues, whether they be wanderers or no, and notwithstanding any licence whatsoever from the king, or any other person or persons, to that purpose. The lord mayor, the sheriffs, and the justices of the peace were ordered to have all galleries, boxes, and seats, in any building used for theatrical representations, at once pulled down and demolished. A fine of five shillings was inflicted upon any person attending such illegal performances, all money taken at the doors was to be confiscated for the benefit of the poor of the parish; and last, but not least, any player caught in the act was to be publicly whipped, and compelled to find sureties for future good-behaviour. If he dared to offend a second time, he was to be considered an incorrigible rogue, 'and dealt with as an incorrigible rogue ought to be. For a time parliament seems to have attained its object in completely suppressing the drama, but as soon as the war was over, the actors who had passed through it unscathed returned to their old haunts; and these waifs and strays of the various old companies, uniting their forces in the winter of 1648, obtained possession of the Cockpit in Drury Lane, and attempted, in a quiet way, to supply the town with its favourite recreation. For a few days they were allowed to act without interference, but one afternoon, during the performance of The Bloody Brother, a troop of soldiers entered the house, turned the disappointed playgoers out, and carried the actors to prison in their stage-clothes. To prevent further infraction of the law, a provost-marshal was appointed, who was expressly instructed to seize all ballad-singers, and suppress all stage-plays. Under the Protectorate, this stringency seems to have been relaxed. Plays were acted privately a little way out of town, and at Christmas and Bartholomew-tide, the players managed, by a little bribery, to have performances at the Red Bull, in St. John Street. Friendly noblemen, too, often allowed them to make use of their houses; Goffe, the woman-actor of the Blackfriars theatre, being employed to notify the time and place to all persons whom it might concern. As soon as Cromwell was dead, and the signs of the time gave augury of a restoration of the monarchy, the players grew bolder. Several plays were acted at the above-mentioned theatre in 1659, and by June 1660, the Cockpit was again opened by Rhodes, and the Salisbury Court Theatre by Beeston. When Charles was fairly seated on the throne, the drama was soon legalised by the granting of two patents, one to Sir William Davenant, and the king's servants at Drury Lane, and the other to Killigrew and the duke's servants at Dorset Gardens-and so ended the puritanical suppression of stage-plays. In the reign of Elizabeth, somewhere about the year 1580, there had been a partial suppression of theatres. Certain 'godly citizens and well-disposed gentlemen of London,' brought such a pressure to bear upon the city magistrates, that the latter petitioned her majesty to expel all players from London, and permit them to destroy every theatre within their jurisdiction. Their prayer was granted, and the several playhouses in Gracechurch Street, Bishopsgate Street, Whitefriars, Ludgate Hill, and near St. Paul's, 'were quite put down and sup-pressed by these religious senators.' The houses outside the city-boundaries were, fortunately, in no way molested, or English literature would have been the poorer by some of Shakspeare's greatest works. Whenever the plague made its appearance in London, the drama went to the wall; and as long as it stayed in town, the players were forced to be idle. Sir Henry Herbert's office-book contains the following memorandum: On Thursday morning the 23rd of February, the bill of the plague made the number of forty-four, upon which decrease the king gave the players their liberty, and they began the 24th February 1636. The plague increasing, the players lay still until the 2nd of October, when they had leave to play. Of course the closing of the theatres was rigidly enjoined during the Great Plague, but the court was only too glad to seize the earliest opportunity of opening them again. Pepys says, in his Diary, under date 20th November 1666.-' To church, it being Thanksgiving day for the cessation of the plague; but the town do say, that it is hastened before the plague is quite over, there being some people still ill of it; but only to get ground of plays to be publicly acted, which the bishops would not suffer till the plague was over.' A FLYING SHIP IN 1709In No. 56 of the Evening Post, a newspaper published in the reign of Queen Anne, and bearing date 20th-22nd December 1709, we find the following curious description of a Flying Ship, stated to have been lately invented by a Brazilian priest, and brought under the notice of the king of Portugal in the following address, translated from the Portuguese: Father Bartholomew Laurent says that he has found out an Invention, by the Help of which one may more speedily travel through the Air than any other Way either by Sea or Land, so that one may go 200 Miles in 24 Hours; send Orders and Conclusions of Councils to Generals, in a manner, as soon as they are determined in private Cabinets; which will be so much the more Advantageous to your Majesty, as your Dominions lie far remote from one another, and which for want of Councils cannot be maintained nor augmented in Revenues and Extent. Merchants may have their Merchandize, and send Letters and Packets more conveniently. Places besieged may be Supply'd with Necessaries and Succours. Moreover, we may transport out of such Places what we please, and the Enemy cannot hinder it: The Portuguese have Discovered unknown Countries bordering upon the Extremity of the Globe: And it will contribute to their greater Glory to be Authors of so Admirable a Machine, which so many nations have in vain attempted. Many Misfortunes and Shipwrecks have happened for want of Maps, but by this Invention the Earth will be more exactly Measur'd than ever, besides many other Advantages worthy of your Majesty's Encouragement. But to prevent the many Disorders that may be occasioned by the Usefulness of this Machine, Care is to be taken that the Use and full Power over the same be committed to one Person only, to whom your Majesty will please to give a strict Command, that whoever shall presume to transgress the Orders herein mentioned shall be Severely punished. May it please your Majesty to grant your humble Petitioner the Priviledge that no Person shall presume to Use, or make this Ship, without the Express Licence of the Petitioner, and his Heirs, under the Penalty of the loss and Forfeiture of all his Lands and ,Goods, so that one half of the same may belong to the Petitioner, and the other to the Informer. And this to be executed throughout all your Dominions upon the Transgressors, without Exception or Distinction of Persons, who likewise may be declared liable to an Arbitrary punishment, &c. Of this much-vaunted invention an engraving is given in the same newspaper, and is here presented to the reader, who may probably be equally amused by the figure delineated, and the explanation of its uses, as subjoined.  An Explanation of the Figure. This extraordinary aerial locomotive is perhaps one of the most curious of these apparatuses for the purpose of flying, of which we find numerous instances from the middle ages downwards. A more extended knowledge of the laws of gravity, and the relations subsisting between us and the atmosphere surrounding our globe, has induced us to discard all such attempts at emulating the powers of the feathered tribes of creation as chimerical. By means of balloons, indeed, first made available by Montgolfier in the latter half of the eighteenth century, we have been enabled to overcome, in a limited, degree, the obstacles which prevent us from soaring above the surface of the earth. But it is very significant, that whilst in all other means of locomotion we have made such rapid strides within the last hundred years, the science of aeronautics has advanced little beyond the point which it attained in the days of our grandfathers. In connection with this subject, we may allude to a well-known story of an Italian charlatan who visited Scotland in the reign of James IV, and insinuated himself so successfully into the good graces of that monarch, as to be created abbot of Tungland. The following account of his proceedings is thus quaintly given by Bishop Lesley, and quoted by Mr. Wilson in his Prehistoric Annals of Scotland. He causet the king believe that he, be multiplyinge and utheris his inventions, wold make fine golde of uther metall, quhilk science he callit the quintassence; quhairupon the king maid greit cost, bot all in vain. This Abbott tuik in hand to flie with wingis, and to be in Fraunce befoir the saidis ambassadouris; and to that effect he causet mak ane pair of wingis of fedderis, quhilkis beand fessenit apoun him, he flew of the Castell wall of Striveling [Stirling], hot shortlie he fell to the ground and brak his thee-bane. Bot the wyt [blame] thairof he ascryvit to that thair was sum hen fedderis in the wingis, quhilk yarnit and covet the mydding [dunghill] and not the skyis. How far this very philosophical mode of accounting for the failure of his project was successful in maintaining his credit with James we are not informed, but we opine it were but a sorry solace for a broken limb. It is a little curious that, in the year 1777, a similar experiment is recorded to have been made at Paris, on a convict from the galleys. The man was surrounded with whirls of feathers, curiously interlaced, and extending gradually at suitable distances, in a horizontal direction from his feet to his neck. Thus accoutred, he was let down from a height of seventy Paris feet, descended slowly, and fell on his feet uninjured, in the presence of an immense body of spectators. He complained of a feeling like sea-sickness, but experienced no pain otherwise. THE COMMONWEALTH OF HADESThe aberrations of the human intellect have, perhaps, never assumed more extraordinary forms than in the history of magic and witchcraft. The belief in demons has existed in all ages of known history, and among the pagan peoples, it was almost a more important part of the vocation of the priesthood to control the evil spirits than to conduct the worship of the beneficent deities; at all events, it was that ascribed faculty which gave them the greatest influence over their ignorant votaries. The introduction of Christianity did not discourage the belief in demons, but, on the contrary, it was the means of greatly increasing their numbers. Not only were the multiform spirits of the then popular creeds, such as satyrs, wood-nymphs, elves, &c., accepted as demons, but all the false gods of the pagans were placed in the same category, and thus was introduced into medieval magic a host of names of individual demons, taken from all countries, to the effect, necessarily, of creating very confused ideas on a subject which, in the olden time, had been tolerably clear even to the vulgar. When the learned men of the middle ages began to take demonology into their hands, they sought to reduce this confusion into order by arranging and classifying, and they soon produced an elaborate system of orders and ranks, and turned the infernal regions into a regular monarchy, modelled upon the empires of this world, with offices and dignities imitated from the same pattern. It was in the course of the fifteenth and sixteenth century that this system of a demoniacal commonwealth received its full development; and men like Johannes Wierus, who published his Pseudomonarchia Daemonum in the latter of these two centuries, and the other writers of his class and of that period, were able to give a minute account of all its details. They are amusing enough, and the subject is, in many points of view, very interesting. According to these writers, the emperor of the demons was Belzebuth or Belzebub. He is said to have been worshipped by the people of Canaan under the form of a fly, and hence he is said to have founded the Order of the Fly; the only order of knighthood which appears to have existed among the demons. When these writers became acquainted with Hades, a revolution had taken place there, and Satan, who had formerly been monarch, had been dethroned and Belzebub raised to his place. Satan had now placed himself at the head of the opposition party. Among the great princes were: The ministers of state of Belzebuth's court were: Belzebuth had his ambassadors also, and their different appointments were, perhaps, intended to convey a little satire on the different countries to which they were sent. They were: Among other high officers were, Lucifer, who was grand - justiciary and minister of justice; and Alastor, who held the distinguished office of executioner. The officers of the household of the princes were: There were also certain ministers or officers of the privy-purse of Belzebuth, such as: With a court so complicated in its arrangements, and numerous in its officers, we might, perhaps, like to know what was the population of Belzebuth's empire. Wierus has not left us without full information, for he tells us that there are in hell, 6666 legions of demons, each legion composed of 6666 demons, which, therefore, makes the whole number amount to 44,435,556. Whoever wishes for further information, need only have recourse to Johannes Wierus, and he may obtain as much as he can possibly desire. It must not be forgotten that these statements were at one time fully believed in by men of education and intellect. |