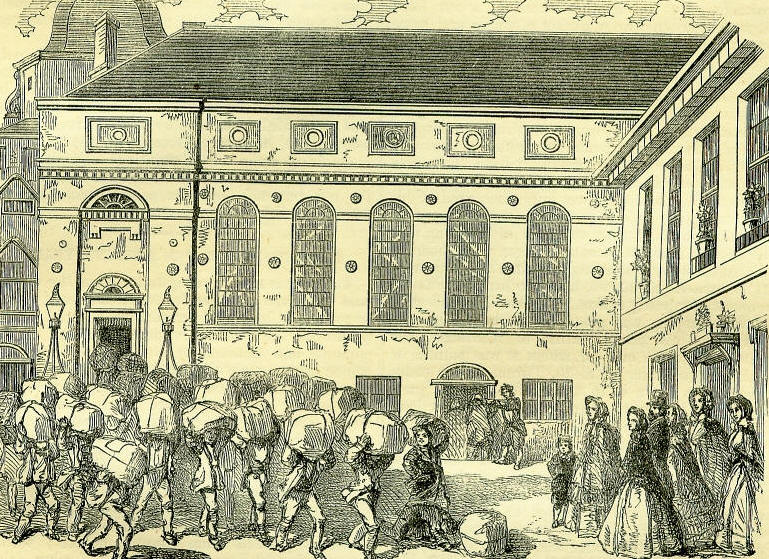

19th DecemberBorn: Charles William Scheele, distinguished chemist, 1742, Stralsund; Captain William Edward Parry, Arctic navigator, 1790, Bath. Died: Frederick Melchior, Baron Grimm, statesman and wit, 1807, Gotha; Benjamin Smith Barton, American naturalist, 1815; Augustus Pugin, architectural draftsman, 1832; Joseph Mallord William Turner, painter, 1851, Chelsea. Feast Day: St. Nemesion, and others, martyrs, 250. St. Samthana, virgin and abbess, 738. J. M. W. TURNERJoseph Mallord William Turner, R.A., was the son of a barber, and was born at his father's shop, in Maiden Lane, in London, in 1775. The friendly chat of the celebrities of the time in that room of frizzling and curling, persuaded Turner, the father, that his son would become a great man; so he gave him a very fair education, and in his rude way encouraged the lad's taste for art. The son formed a close friendship with a clever young artist like himself, Girtin, who would have been, had he lived, some critics say, his great rival. Turner himself used good-naturedly to assert: If poor Tom had lived, I should have starved. In 1789, Turner entered the Royal Academy as a student. After remaining there in that capacity for five years, and working actively at his profession for other five, during which periods he sent to the exhibition no less than fifty-nine pictures, he was elected in 1799 an associate of the Royal Academy. In the two following years he exhibited fourteen pictures, and in 1802 was elected an academician. Till this date he had chiefly been known as a landscape painter in water-colours, but thenceforth he turned his attention to oil-painting, and in the ensuing half-century produced at the Academy exhibitions upwards of two hundred pictures. In 1807, he was elected professor of perspective in the Royal Academy, and the following year appeared his Liber Studiorum, or Book of Studies, which Charles Turner, Mr. Lupton, and others, engraved. Other engraved works by him are his illustrations of Lord Byron's and Sir Walter Scott's poems; Roger's Italy and Poems; The Rivers of England; The Rivers of France, and Scenery of the Southern Coast. To enumerate the different paintings of Turner would be impossible. They have established him as the greatest of English landscape painters, and earned for him the appellation of the 'English Claude,' to whom, indeed, many of his admirers pronounce him superior. Among his more famous pictures, reference may specially be made to his Kilchurn Castle, Loch Awe;' 'The Tenth Plague of Egypt;' 'The Wreck of the Minotaur;' 'Calais Pier;' 'The Fighting Temeraire Tugged to her Last Berth;' 'The Grand Canal, Venice;' ' Dido and Eneas;' 'The Golden Bough;' 'Modern Italy;' 'The Fall of Carthage,' and 'The Building of Carthage.' The sea in all its varied aspects, but chiefly under that of gloom or tempests; bright sunny landscapes and noble buildings, lighted up by the glowing rays of the setting sun; and generally nature in her weird-like and unwonted moods, form the favourite themes of this great artist. Through all his productions the genius of a poet declares itself, impressing us with the same mysterious feeling of ineffable grandeur that we experience in reading the works of Dante or Milton. The eccentricity of his colouring and indefiniteness of his figures, rendering many of his later pictures, to ordinary observers, nothing more than a splash or unmeaning medley, have been frequently animadverted on; and with respect to the pictures executed during the last twenty years of his life, it cannot be denied, notwithstanding their unfailing suggestiveness, that much of this censure is well founded. The Royal Academy treated Turner well, and he, in return, adhered to it devotedly to his death, But the prime of his life was spent in struggles with poverty, in unmerited obscurity, and battles with his employers. He had a rigid sense of justice, and a proud consciousness of his own merits and the dignity of his art. The pertinacity with which he exacted the last shilling in all cases made him seem mean. The natural way in which he continued to retain the simple, we might say uncouth, habits which poverty taught him, after he became wealthy, caused him to be branded as a miser. His gruff and peculiar ways, his honesty, as well as his proficiency, made him many enemies. But he lived to reach a high pinnacle of popularity, and to know himself fairly appreciated. Turner's life is a strange story, a narrative at once painfully and pleasingly interesting. Many seeds of human frailty, many taints of a vulgar origin were never uprooted, though ever kept in check by a truly noble soul. Turner was emphatically a child of nature. His faults were natural frailties not restrained, his virtues rather good impulses than acquired principles. When he rudely dismissed a beggar-woman, and then ran after her with a five-pound note, he furnished a key which unlocks his whole life. We must set one thing against another. Turner was rough and blunt; yet of how many could it be said, that 'he was never known to say an ill word of any human being, never heard to utter one word of depreciation of a brother-artist's work?' Let the reader learn to wonder at Turner's greatness, by applying to himself such a test. A curious tale is told of his obstinacy. He was visiting at Lord Egremont's. He and his host quarrelled so desperately as to whether the number of windows in a certain building was six or seven, that the carriage was ordered, and Turner driven to the spot, to count them for himself, and be convinced of his mistake. But on another occasion, when Lord Egremont ordered up a bucket of water and some carrots, to settle a question about their swimming, Turner proved to be in the right. He was fond of privacy, and on this subject Chantrey's stratagem, by which he got into the artist's studio, long remained a standing joke against Turner. There were some things, unhappily, connected with his private life, which were wisely kept concealed; and when, to an unknown residence, which he had at Chelsea, the old man retired at last to die, he was only discovered by his friends the day before his final journey. Undoubtedly, Turner was fond of hoarding, but he was too great to become a miser. He hoarded his sketches even more eagerly than his sixpences. If he amassed £140,000, it was to leave it to found a charity for needy artists. This was his life's wish. If his grasping was great, his pride was greater. For when his grand picture of 'Carthage' was refused by some one, for whom it was painted to order, at the price of £100, Turner, in his pride, resolved to leave it to the nation. 'At a great meeting at Somerset House, where Sir Robert Peel, Lord Hardinge, and others were present, it was unanimously agreed to buy two pictures of Turner, and to present them to the National Gallery, as monuments of art for eternal incitement and instruction to artists and all art-lovers. A memorial was drawn up, and presented to Turner by his sincere old friend, Mr. Griffiths, who exulted in the pleasant task. The offer was £5000 for the two pictures, the 'Rise,' and 'Fall of Carthage.' Turner read the memorial, and his eyes brightened. He was deeply moved: he shed tears; for he was capable, as all who knew him well knew, of intense feeling. He expressed the pride and delight he felt at such a noble offer from such men, but he added sternly, directly he read the word 'Carthage'-'No, no; they shall not have it,' at the same time informing Mr. Griffiths of his prior intention. All his friends loved him, and he was really, as we have stated, no miser. There was silver found under his pillow, when he left any place he had been staying at; but this was because he was too sensitive to offer it to the servants in person. We read of him paying, of his own accord, for expensive artist-dinners, of his giving a merry picnic, of his sending upwards of £20,000 secretly to the aid of a former patron. Turner was generous-hearted, too, in other than pecuniary matters. He pulled his own picture down, to find a place for the picture of some insignificant young artist, whom he wished to encourage. He blackened a bright sky in one of his academy pictures, which hung between two of Lawrence's, so as to cast its merits into the shade. In this befouled condition, he allowed his own production to remain throughout the exhibition; and whispered to a friend, to allay his indignation: 'Poor Lawrence was so distressed; never mind, it'll wash off; it 's only lampblack!' His genuine affections were never drawn out. The history of his first love is a sad story of disappointment, enough to darken a life. He always stuck close to his old 'dad,' as he called him; but quitted, much to the old man's disappointment, a pleasant country-house and garden, for a dull house in town. The reason for this proceeding oozed out one day in conversation with a friend: 'Dad would work in the garden, and was always catching cold.' This great artist's will, after all, was so loosely expressed, that its intentions were to a great extent frustrated, and the bulk of his property, which he had bequeathed for national and artistic purposes, was successfully claimed by his relatives. By a compromise, however, effected with the latter, the magnificent series of oil-paintings and drawing,, known as the Turner Collection, have been secured for our national galleries as the most exalted trophies of British art. ALMANACS FOR THE ENSUING YEARThe year is now drawing to its close, the Christmas festivities are in active preparation, and almost every one is looking forward with cheerful anticipation to the welcome variety from the regular pursuits and monotonous routine of ordinary life, which characterises the death of the Old year, and the birth of the New one. Youngsters at school are looking eagerly forward to the delights of home and the holidays-the intermission from study and scholastic restraint; the sliding, skating, and other sports of the season; the mince-pies, the parties, and the pantomimes. A universal bustle and anticipation everywhere prevails. Hampers with turkeys, geese, bacon, and other substantial provisions are coming up in shoals to town as presents from country friends; whilst barrels of pickled oysters, and boxes of cakes, dried fruits, and bonbons find their way in no less force to the provinces. Nor in thus providing for material and gastronomic enjoyment, are the more refined and intellectual cravings of humanity neglected. Christmas-books of all shapes, sizes, and subject-matter blaze forth magnificently in booksellers' windows, decked in all the colours of the rainbow, resplendent in all the gorgeousness of modern bookbinding, and displaying the grandest trophies of typographic and illustrative skill. The publishers of the various popular periodicals now put forth the 'extra Christmas number,' and the interest and curiosity excited by this last are shared with the graver and more business-like 'almanacs for the ensuing year.' The time-honoured street-cry just quoted, may still be heard echoing through many of our public thoroughfares, though it is probably much less common now than it used to be, when itinerant venders of all kinds found a greater toleration from the authorities, and a far readier market with the public for their wares. In the present day, people generally resort to the regular book-sellers or stationers for their almanacs. Here purchasers of all means and tastes may be suited, whether they desire a large and comprehensive almanac, which, in addition to the mere calendar, may furnish them with information on all matters of business and general utility throughout the year, or whether they belong to that class whose humble wants in this direction are satisfied by the expenditure of a penny. It is well known that the Stationers' Company of London enjoyed, in former times, a monopoly of the printing of all books; and long after this privilege had gradually been withdrawn from them, they continued to assert the exclusive right of publishing almanacs; but this claim was successfully contested in 1775 by Thomas Carnan, a book-seller in St. Paul's Churchyard, who obtained a decision against the company in the Court of Common Pleas, and this judgment was subsequently concurred in by parliament, after an animated discussion. The Stationers' Company continued the publication of almanacs with considerable profit to themselves, notwithstanding this infringement of what they deemed a vested right; and to the present day this branch of trade, the sole relic of a business which formerly comprehended the whole world of literature, forms, in spite of competition, a most profitable source of revenue to the association.  Almanac Day' at Stationer's Hall The day on which the Stationers' Company issue their almanacs to the public (on or near the 22nd November) presents a very animated and exciting scene, and is delineated in the accompanying engraving. We quote the following description from Knight's London: Let us step into Ludgate Street, and from thence through the narrow court on the northern side to the Hall. The exterior seems to tell us nothing, to suggest nothing, unless it be that of a very commonplace looking erection of the seventeenth century, and therefore built after the fire which destroyed everything in this neighbourhood; so we enter. Ha! here are signs of business. The Stationers cannot, like so many of its municipal brethren, be called a dozing company; indeed it has a reputation for a quality of a somewhat opposite kind. All over the long tables that extend through the hall, which is of considerable size, and piled up in tall heaps on the floor, are canvas bales or bags innumerable. This is the 22nd of November. The doors are locked as yet, but will be opened presently for a novel scene. The clock strikes, wide asunder start the gates, and in they come, a whole army of porters, darting hither and thither, and seizing the said bags, in many instances as big as themselves. Before we can well understand what is the matter, men and bags have alike vanished-the hall is clear; another hour or two, and the contents of the latter will be flying along railways, east, west, north, and south; yet another day, and they will be dispersed throughout every city and town, and parish and hamlet of England; the curate will be glancing over the pages of his little book to see what promotions have taken place in the church, and sigh as he thinks of rectories, and deaneries, and bishoprics; the sailor will be deep in the mysteries of tides and new moons that are learnedly expatiated upon in the pages of his; the believer in the stars will be finding new draughts made upon that Bank of Faith, impossible to be broken or made bankrupt-his superstition as he turns over the pages of his Moore-but we have let out our secret. Yes, they are all almanacs-those bags contained nothing but almanacs: Moore's and Partridge's, and Ladies' and Gentlemen's, and Gold-smiths', and Clerical, and White's celestial, or astronomical, and gardening almanacs-the last, by the way, a new one of considerable promise, and we hardly know how many others. It is even so. The-at one time-printers and publishers of everything, Bibles, prayer-books, school-books, religion, divinity, politics, poetry, philosophy, history, have become at last publishers only of these almanacs and 'prognostications,' which once served but to eke out the small means of their poorer members. And even in almanacs they have no longer a monopoly. Hundreds of competitors are in the field. And, notwithstanding, the Stationers are a thriving company. In the general progress of literature, the smallest and humblest of its departments has become so important as to support in vigorous prosperity, in spite of a most vigorous opposition, the company, in which all literature-in a trading sense-was at one time centered and monopolised! ' It is not necessary here to enter into the history of almanacs, a subject which has already been thoroughly discussed in the introduction to this work. We may remark, nevertheless, that till a comparatively recent period, the general subject-matter of which the majority of almanacs was composed, reflected little credit, either on the general progress of the nation in intelligence, or the renowned company by whom these books were supplied. The gross superstitions and even indecencies which disfigured Poor Relict's Almanac, and the predictions and other absurdities of the publications bearing the names of Partridge and Moore, continued to flourish with unimpaired vigour up to 1828. In that year, the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge issued in the British Almanac a quiet protest against the worthless pabulum hitherto supplied to the public. This new work both found extended favour with the public, and produced a signal reform in most of the popular almanacs. In the following year, Poor Robin disappeared altogether from the stage; a great portion of the astrology which pervaded the other almanacs was retrenched; and since that period the publications of the Stationers' Company have kept pace with the growing requirements and improved tastes of the age. LONDON STREET NOMENCLATUREThe sponsors of Old London performed their duties more conscientiously than most of their successors; as a consequence, the names of the older streets of the capital serve not only as keys to their several histories, but as landmarks by which we can measure the changes wrought by time in the topographical features of the city. The streams which once murmured pleasantly near the abodes of the Londoners have long since been degraded into sewers, but their memory is pre-served in the streets of Fleet, Walbrook, and Holborn (old bourne), the ward of Lanz bourne, and the parish of St. Marylebone-a corruption of St. Mary-le-bourne. The favourite trysting-places of the youthful citizens, the wells to which. they flocked in the sweet summer-time, have left their names to Clerkenwell, Holywell Street, Bridewell, and Monkwell Street; as the mineral springs have to Spafields and Bagnigge Wells Road. The wall that encompassed the city has disappeared, with all its gates, but London Wall, Aldgate, Aldersgate, Moorgate, Bishopsgate, Newgate, Cripplegate, and Ludgate, are still familiar words. Barbican marks the site of the ancient burgh-kenning or watch-tower. Covent Garden and Hatton Garden remind us that trees bore fruit and flowers once bloomed. in these now stony precincts, while Vine Street (the site of the vineyard of the royal palace at Westminster), and Vinegar Yard, Drury Lane (originally Vine-garden Yard), speak of the still more distant day when the grape was cultivated successfully in town. Cheapside was the principal market or chepe in London; the fish-market was held in Fish Street, the herb-market in Grass (Grace) Church Street, corn-dealers congregated in Cornhill, bakers in Bread Street, and dairymen in Milk Street. Friday Street takes its name from a fish-market opened there on Fridays. Goldsmith's Row, Silver Street, Hosier Street, Cordwainer Street (now Bow Lane), and the Poultry, were inhabited respectively by goldsmiths, silversmiths, stocking-sellers, boot-makers, and poulterers. Garlick Hill was famous for its garlic. In Sermon, or Shermonier's Lane, dwelt the cutters of the metal to be coined into pence. Ave-Maria Lane, Creed Lane, and Paternoster Row, were occupied principally by the writers and publishers of books containing the alphabet, ayes, creeds, and paternosters. Cloth-fair was the resort of drapers and clothiers, and the Haymarket justified its name until 1830, when the market was removed to another quarter. The Northumberland lion still looks over Charing Cross, and a peer of the realm resides, or did reside a few years ago, in Islington, yet no one would look for a duke in Clerkenwell, or expect to find aristocratic mansions just out of the lord mayor's jurisdiction. Such associations were not always incongruous, the town-houses of the Earls of Aylesbury and the Dukes of Newcastle stood on the ground now occupied by Aylesbury and Newcastle Streets, Clerkenwell; Devonshire House did not give way to the square of that name (Bishopsgate Without) till the year 1690, and in earlier times the kingmaker feasted his dependents where Warwick Lane abuts on Newgate Street. Succumbing to fashion's constant cry of 'Westward ho!' the old mansions of the nobility have been pulled down one by one, bequeathing their names to the houses erected on their sites. To this aristocratic migration London owes its squares of Bedford, Berkeley, Leicester, and Salisbury, and the streets rejoicing in the high-sounding names of Exeter, Grafton, Newport, Albemarle, Montague, Arundel, Argyll, Brooke, Burleigh, Chesterfield, and Coventry. Clare-market tells where the town-house of the Earls of Clare stood. Essex Street (Strand) takes its name from the mansion of Elizabeth's ill-fated favourite; Dorset Court (Fleet Street), from that of the poetical earl; and Scotland Yard marks the site of the lodging used by the kings of Scotland and their ambassadors. Bangor Court (Shoe Lane), Durham Street (Strand), Bonner's Fields, Ely Place (Holborn), and York Buildings (Strand) are called after long-vanished episcopal palaces. The religious houses of the Dominican, Augustine, White and Crouched Friars, have their memory preserved in Blackfriars, Austin-friars, Whitefriars, and Crutched-friars. Mincing-lane derived its name from certain tenements belonging to the nuns or minchuns of St. Helen, and Spitalfields took its appellation from the neighbouring priory of St. Mary Spital. Euston Square, Fitzroy Square, Russell Square, Tavistock Street, Portland Place, and Portman Square, are named after the titles of the ground-landlords; one celebrated nobleman has thus commemorated both name and dignity in George Street, Villiers Street, Duke Street, Of Alley, and Buckingham Street. Woburn Square, Eaton Square, and Ecclestown Street, Pimlico, were named after the country-seats of the landowners who built them. Sometimes street names have been conferred in compliment to individuals more or less famous. Charles, King, and Henrietta Streets, Covent Garden, and Queen's Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields, were so styled in honour of Charles I. and his consort; Charles Street, James Square, was named after the Merry Monarch; York and James Streets (Covent Garden), after his brother. Rupert Street (Haymarket) was so designated after fiery Rupert of the Rhine; Princes Street, Wardour Street, after James I's eldest son, whose military garden occupied a portion of the site; Nassau Street, Soho, was so called in compliment to William III; Queen's Square (Bloomsbury), after Queen Anne; and Hanover Square, in honour of her successor. Later, still, we have Regent Street, King William Street, Adelaide Street, with Victoria and Albert Streets without number. Theobald's Road was James I's route to his Hertfordshire hunting-seat; King's Road, Chelsea, George III's favourite road to Kew. The famous 'Mr. Harley,' afterwards Earl of Oxford, gave Oxford Street its name; Denvill Street (Clare Market) was called after one of the five members whose attempted arrest by Charles I was the commencement of the momentous struggle between King and Commons. The list of 'In Memoriam' streets is a long one; among them are Greville Street, Holborn-from Fulke Greville, the friend of Sir Philip Sidney; Hans Place and Sloane Street-after Sir Hans Sloane, the architect of the Bank of England, and Lord of Chelsea Manor; Southampton Street, Strand-in honour of Lady Rachel Russell, the model-wife, who was a daughter of the Earl of Southampton; Suffolk Street, Southwark-after Brandon, the earl of that name, who married Henry VIII's sister, Mary; Stafford Row, Pimlico-from Lord Stafford, one of Oates's victims; Throgmorton Street-from Sir Nicholas Throgmorton, said to have been poisoned by the Earl of Leicester; Hare Court Temple--after Sir N. Hare, Master of the Rolls in the reign of Elizabeth; Cumberland Street and Gate-after the victor of Culloden Field. Literary celebrities come in for but a small share of brick-and-mortar compliments. Mrs. Montagu, the authoress, lives in Montagu Place (Portman Square); Killigrew, the wit, has given his name to a court in Scotland Yard; and Milton has received the doubtful compliment of having the notorious Grub Street of the Dunciad days rededicated to him. The founder of the Foundling Hospital is justly commemorated in Great Comm Street; and Lamb, the charitable cloth-worker, who built a conduit at Holborn in 1577, has his munificence recorded in Lamb's Conduit Street. Downing Street takes its name from Sir George Downing, secretary to the treasury in 1667; and the once fashionable Bond Street was called after Henrietta Maria's comptroller of the household. Barton Booth, the Cato of Addison's tragedy, has left his name in Barton Street, Westminster; the adjacent Cowley Street, being called after his birthplace. These are not the only thoroughfares connected with the drama; the site of the old Fortune Theatre is marked by Playhouse Yard (Central Street); and that of the Red Bull Theatre, by Red Bull Yard (St. John's Street Row). Globe Alley and Rose Alley are mementoes of those famous playhouses; while the Curtain Theatre is represented by the road of that name. Apollo Court, Fleet Street, reminds us of Jonson's glorious sons of Apollo. Spring Gardens (Charing Cross) was a favourite resort of pleasure-seekers in Pepy's time, but nought but its name is left now to recall its fame, a fate that has befallen its rival Vauxhall. Old Street was the old highway to the north-eastern parts of the country. Knight Rider Street was the route of knights riding to take part in the Smithfield tournaments. Execution Dock, Wapping, was the scene of the last appearance of many a bold pirate and salt-water thief. Bowl Yard (St Giles's) was the spot where criminals were presented with a bowl of ale on their way to Tyburn. Finsbiuy and Moorfields were originally fens and moors; Houndsditch was an open ditch noted for the number of dead dogs cast into it; Shoreditch was known as Soersditch long before the goldsmith's frail wife existed. Paul's Chain owes its name to a chain or barrier that used to be drawn across St. Paul's Churchyard, to insure quietness during the hours of divine worship. The Great and Little Turnstiles were originally closed by revolving barriers, in order to keep the cattle pastured in Lincoln's Inn Fields from straying into Holborn. The Sanctuary (Westminster) was once what its name implies. The Birdcage-Walk (St James's Park) derived its name from an aviary formed by James I. The aristocratic neighbourhood of May Fair is so called from the annual fair of St. James, which was held there till the year 1809. Corruption has done its work with street-names. The popular love of abbreviation has transformed the Via de Alwych (the old name for Drury Lane) into Wych Street, and Gatherum into Gutter Lane, while vulgar mispronunciation has altered Desmond into Deadman's Place, Sidon into Sything and Seething Lane, Candlewick into Cannon Street, Strypes Court (named after the historian's father) into Tripe Court, St. Olave's into Tooley Street, Golding into Golden Square, Birch over into Birchin Lane, Blanche-Appleton into Blind-chapel Court, and Knightenguild Lane (so called from tenements pertaining to the knighten-guild created by Edgar the Saxon) into Nightingale Lane. Battersea figures in Domesday Book as Patricesy, passing to its present form through the intermediate ones of Baltrichsey and Battersey; Chelsea, known to the Saxons as Cealchylle, and to Sir Thomas More as Chelcith, is, according to Norden, 'so called from the nature of the place, whose strand is like the diesel, coesel or cesol, which the sea casteth up, of sand and pebble stones, thereof called. Cheselsey, briefly Chelsey.' In the fourteenth century, Kentish-town was known as Kamiteloe; Lambeth assumes the various shapes of Lamedh, Lamhee, Lamheth, and Lambyth; Stepney was once Stebenhede, and afterwards Stebenhytlie; Islington took the form of Isendune, Iseldon or Eyseldon; Kensington was Chenesitune, and Knightsbridge appears in the reign of Edward. III as 'the town of Knighbrigg.' Other changes have been wrought by mere caprice. There may have been reasons for converting Petty Prance into New Broad. Street, Dirty Street into Abingdon Street, Stinking Lane, otherwise Chick Lane, otherwise Blow-bladder Lane, otherwise Butcher-hall Lane, into King Edward Street, Knave's Acre into Poultney Street, Duck Lane into Duke Street, and Pedlar's Acre into Belvedere Road; but Cato Street (the scene of Thistlewood's conspiracy), Monmouth Street (celebrated for its frippery and second-hand garments), Dyot Street, and Shire Lane (which marked the line of boundary between the city and the county), might well have been left in possession of these old names; nothing has been gained by rechristening them Homer Street, Dudley Street, George Street, and Lower Searle's Place. |