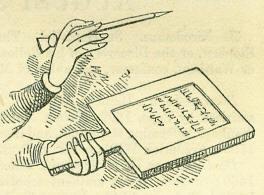

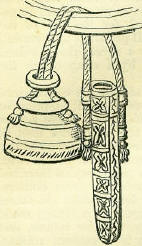

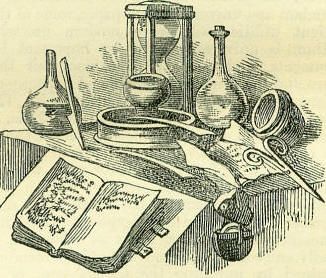

2nd AugustBorn: Pope Leo XII, 1760; Cardinal Nicholas Wiseman, 1802, Seville. Died: Archidamus III, king of Sparta, son of Agesilaus, B.C. 338, Lucania, in Italy; Quintilius Varus, Roman governor in Germany, A.D. 10; William II (Rufus) of England, killed in the New Forest, Hampshire, 1100; Henry III, king of France, stabbed the previous day by Jacques Clement, 1589, St. Cloud; Etienne Bonnet de Condillac, abbe, author of Traitĕ des Sensations, Cows d'Etudcs, &c., 1780, Flux, near Beaugenci; Thomas Gainsborough, great landscape painter, 1788; Mehemet Ali, paella of Egypt, 1849; Lord Herbert of Lea, British statesman, 1861, Wilton House, Salisbury. Feast Day: St. Stephen, pope and martyr, 257; St. Etheldritha or Alfrida, virgin, about 834. DEATH OF WILLIAM RUFUSFew Englishmen of the nineteenth century can realize a correct idea of the miseries endured by their forefathers, from the game-laws, under despotic princes. Constant encroachments upon private property, cruel punishments-such as tearing out the offender's eyes, or mutilating his limbs-inflicted for the infraction of forest law; extravagant payments in the shape of heavy tolls levied by the rangers on all merchandise passing within the purlieus of a royal chase; frequent and arbitrary changes of boundary, in order to bring offences within the forest jurisdiction, were only a portion of the evils submitted to by the victims of feudal tyranny. No dogs, however valuable or dear to their owners-except mastiffs for household defence -were allowed to exist within miles of the outskirts, and even the poor watch-dog, by a 'Court of Regard' held for that special purpose every three years, was crippled by the amputation of three claws of the forefeet close to the skin-an operation, in woodland parlance, termed expeditation, intended to render impossible the chasing or otherwise incommoding the deer in their coverts. Of all our monarchs of Norman race, none more rigorously enforced these tyrannous game-laws than William Rufus; none so remorselessly punished his English subjects for their infraction. Even the Conqueror himself, who introduced them, was more indulgent. No man of Saxon descent dared to approach the royal preserves, except at the peril of his life. The old forest rhyme: Dog draw-stable stand, Back berand-bloody hand, provided for every possible contingency; and the trespasser was hung up to the nearest convenient tree with his own bowstring. The poor Saxons, thus worried, adopted the impotent revenge of nicknaming Rufus 'Wood-keeper,' and 'Herdsmen of wild beasts.' Their minds, too, were possessed with a rude and not unnatural superstition, that the devil in various shapes, and under the most appalling circumstances, appeared to their persecutors when chasing the deer in these newly-formed hunting -grounds. Chance had made the English forests-the New Forest especially-fatal to no less than three descendants of their Norman invader, and the popular belief in these demon visitations received additional confirmation from each recurring catastrophe; Richard, the Conqueror's eldest son, hunting there, was gored to death by a stag; the son of Duke Robert, and nephew of Rufus, lost his life by being dashed against a tree by his unruly horse; and we shall now shew how Rufus himself died by a hunting casualty in the same place. Near Chormingham, and close to the turnpike-road leading from Lymington to Salisbury, there is a lovely secluded dell, into which the western sun alone shines brightly, for heavy masses of foliage encircle it on every other side. It is, indeed, a popular saying of the neighbourhood: that in ancient days a squirrel might be hunted for the distance of six miles, without coming to the ground; and a traveller journey through a long July day without seeing the sun. Long avenues open away on all sides into the deep recesses of those dark woods; and, altogether, it forms just the spot where the hunter following his chase after the ancient Norman fashion of woodcraft, would secrete himself to await the passing game-a fashion which Shakspeare has thus graphically described: Enter SKINKLO and HUMPHREY, with cross-bows in their hands. Skinklo. Under this thick grown brake we'll hide ourselves, For through this laund anon the deer will come; And in this covert we will take our stand, Cullng the principal of all the deer. Humphrey. I'll stay above the hill, so both may shoot. Skinklo. That cannot be-the noise of thy cross-bow Will scare the herd, and so my shot is lost. Here stand we both and shoot we at the best. His friends had dispersed to various coverts, and there remained alone with Rufus, Sir Walter Tyrrel, a French knight, whose unrivalled adroitness in archery raised him high in the Norman Nimrod's favour. That morning, a workman had brought to the palace six cross-bow quarrels of superior manufacture, and keenly pointed, as an offering to his prince. They pleased him well, and after presenting to the fellow a suitable guerdon, he handed three of the arrows to Tyrrel-saying, jocosely, 'Bon archer, lionises flèshes.' The Red King and his accomplished attendant now separated, each stationing himself, still on horseback, in some leafy covert, but nearly opposite; their cross-bows bent, and with an arrow upon the nut. The deep mellow cry of a stab hound, mingled with the shouts of attendant foresters, comes freshening on the breeze. There is a crash amongst the underwood, and out bounds 'a stag of ten,' that after listening and gazing about him, as deer are wont to do, commenced feeding behind the stem of a tall oak. Rufus drew the trigger of his weapon, but, owing to the string breaking, his arrow fell short. Enraged at this, and fearful the animal would escape, he exclaimed, Tirez done, Walter! tirez done! si mĕme cètoit le diablé-Shoot, Walter! shoot! even were it the devil. His behest was too well obeyed; for the arrow glancing off from the tree at an angle, flew towards the spot where Rufus was concealed. A good arrow, and moreover a royal gift, is always worth the trouble of searching for, and the archer went to look for his. The king's horse, grazing at large, first attracted attention; then the hounds cowering over their prostrate master; the fallen cross-bow; and, last of all, the king himself prone upon his face, still struggling with the arrow, which he had broken off short in the wound. Terrified at the accident, the unintentional homicide spurred his horse to the shore, embarked for France, and joined the Crusade then just setting for the East. About sun-down, one Purkiss, a charcoal-burner, driving homewards with his cart, discovered a gentleman lying weltering in blood, with an arrow driven deep into his breast. The peasant knew him not, but conjecturing him to be one of the royal train, he lifted the body into his vehicle, and proceeded towards Winchester Palace, the blood all the way oozing out between the boards, and leaving its traces upon the road. There is a tradition, that for this service he had some rods of land, to the amount of an acre or two, given to him; and it is very remarkable that a lineal descendant of this charcoal-burner, bearing the same name, does now live in the hut, and in possession of the land, and is himself a charcoal-man; that all the family, from the first, have been of the same calling, and never richer or poorer, the one than the other; always possessed of a horse and cart, but never of a team; the little patrimony of land given to their celebrated ancestor having descended undiminished from father to son.  This family, therefore, is rightly esteemed the most ancient in the county of Hants. A Purkiss of the last century, kept suspended in his hovel the identical axletree made of yew, which had belonged to the aforesaid cart; but which, in a fit of anger, on its accidentally falling on his foot, he reduced to a bag of charcoal, much to the chagrin of the late Duke of Gloucester, who, when appointed ranger of New Forest, was desirous of purchasing it. As to the famous Rufus Oak, after being reduced to a stump by the mutilations of relic-seekers, it was privately burned by one William House from mere wantonness. The circumstance was unknown until after his death, otherwise his safety would have been endangered, so highly did the foresters prize the tree, on account of the profits accruing from a host of sight-seekers. Some fragments of the root were preserved, one of which is still extant, inscribed-'Deer 16th, 1751; part of the oak under which King Rufus died, Aug, 2nd, 1100; given me by Lord de la War, C. Lyttleton, Nov. 30th, 1768; given by C. Lyttleton, bishop of Carlisle, to Hen. Baker.' In the year 1745, Lord de la War being head-ranger of New Forest, erected a triangular pillar, bearing suitable inscriptions, on the site of this historical tree, in one of which he states that he had seen the oak growing there. But his lordship's erection has proved a far more evanescent memorial than the oak, it having also been chipped and defaced by relic-hunters; so that it is now as silent on all points of history as the quondom tree. MEHEMET ALIOriental history presents us with numerous instances of men, who have ascended to the highest stations from the humblest grades of society. The throne itself has been attained by individuals, whose antecedents did not differ greatly from those of the Arabian Nights hero, Aladdin. And just as strange and sudden as was their elevation, has often been their downfall. The life of Mehemet Ali, viceroy of Egypt, affords a striking illustration of the first of these remarks, though his success in establishing himself and descendants as hereditary rulers of the country, furnishes an exception to the general slipperiness of the tenure of power in the East. He was of Turkish origin, being a native of the town of Cavalla, in Roumelia, the ancient Macedonia, where he was born about the year 1769. He adopted the trade of a tobacconist, but after carrying it on for a time, abandoned it to enter the army. By his bravery and military skill, he soon received promotion, and on the death of his commander, was appointed his successor, and after-wards married his widow. During the French invasion of Egypt, he was sent thither as the second in command of a contingent of 300 furnished by the town of Cavalla, and greatly distinguished himself in the various engagements with the troops of Bonaparte. For several years after the evacuation of the country by the French, Egypt was distracted by contending factions, Mehemet Ali uniting himself to that of the Mainelukes. At last, in an outbreak at Cairo in 1806, the viceroy, Khoorshid Pasha, was deposed by the populace, who insisted on Mehemet Ali taking the vacant post. This tumultuary election was ratified by a firman from the sultan, who probably saw that the only means of preserving the tranquillity of the country, was by placing Mehemet at the head of affairs. It was wholly disregarded, however, by the old allies of the latter, the Mameluke Beys, and with them, for several years, Mehemet was engaged in a perpetual struggle for supremacy. What he might perhaps have found some difficulty in accomplishing by open hostilities, he determined to effect by treachery. During an interval of tranquillity between the contending parties, the Mamelukes were invited to attend the ceremony of the investiture of Toussoon, Mehemet Ali's son, with the command of the army. About 470 of them, with their chief Ibrahim Bey, responded to the summons, and entered the citadel of Cairo. At the conclusion of the ceremony, they mounted their horses and were proceeding to depart, when a murderous fire of musketry was opened upon them by the viceroy's soldiers, stationed on various commanding positions. The unfortunate Mameluke guests were shot down to a man, for literally only one effected his escape, and that was by the extraordinary feat of leaping his horse over the ramparts. The gallant steed was killed by the fall, but his rider managed, though, it is said, with a broken ankle, to escape to a place of safety. The whole affair leaves an indelible blot on the memory of Mehemet Ali. After this act of treachery, he proceeded to consolidate his power, and gradually became undisputed master of Egypt and its dependencies, though still with nominal recognition of the supremacy of the Sublime Porte. So powerful a vassal might well excite the apprehensions of his superior. In 1831, on the pretext of vindicating a claim against Abdallah Pasha, governor of Acre, he despatched a strong army into Syria, under the command of his son, Ibrahim Pasha, who, in the course of a few months, effected a complete subjugation of the country. The sultan thereupon declared Mehemet Ali a rebel, and sent troops against him into Syria, but the result was only further discomfiture. The powers of Europe then interfered, and through their mediation a treaty of peace was signed, by which Syria was made over to Mehemet Ali, to be held as a fief of the Sublime Porte. After a few years, hostilities were resumed with the sultan, who sought to expel the viceroy from Syria, a project in which he had the countenance of the four European powers-Great Britain, Austria, Russia, and Prussia. Against so formidable a combination Mehemet Ali had no chance, and accordingly, after sustaining a signal defeat near Beyrout, and the blockade of Alexandria by an English squadron, he found himself compelled to come to terms and evacuate Syria in favour of Turkey, the latter power recognising formally the hereditary right to the pashalie of Egypt as vested in him and his family. This agreement was concluded in 1841, eight years before the death of Mehemet All, and was the last public event of importance in his life. That Syria was a gainer by the change of masters, is very doubtful. The vigorous administration of the Egyptian potentate was succeeded by the effete imbecility of the Turkish sway, which in recent years found itself unable to avert the atrocious massacres of Damascus and the Lebanon. As an Oriental and a Mohammedan, Mehemet Ali displays himself wonderfully in advance of the views and tendencies generally characteristic of his race and sect. Instead of superciliously ignoring the superior progress and attainments of European nations, he made it his sedulous study to cope with and derive instruction from them, in all matters of commercial and social improvement. Through the liberal-minded policy carried into practice by him, Egypt, after the slumber and decay of ages, has again taken her place as a flourishing and well-ordered state, and regained in some measure the prestige which she enjoyed in ancient times. Trade with foreign countries has been encouraged and extended, financial and military affairs placed on an organised and improved footing, the cultivation of cotton and mulberries introduced and fostered, and various important public works, such as canals and railways, successfully executed. With the view of initiating his subjects in the arts of European civilisation, young men of intelligence were sent by him to Britain and other countries, and maintained there at his expense, for the purpose of studying the arts and sciences. A perfect toleration in religious matters was observed by him, and under his government Christians were frequently raised to the highest offices of state, and admitted to his intimate friendship. In personal appearance Mehemet All was of short stature, with features so intelligent and agreeable as greatly to prepossess strangers in his favour. He enjoyed till the year before his death an iron constitution, but was so enfeebled by a severe illness which attacked him then, that the duties of government had to be resigned by him to his son Ibrahim Pasha, who survived the transfer little more than two months. In disposition Mehemet All is said to have been frank and open, though the treacherous massacre of the Mamelukes militates strongly against his character in this respect. His magnanimity, as well as commercial discernment, was conspicuous in his permission of the transit of the Indian mails through Egypt, whilst he himself was at war with Britain. The undoubted abilities and sagacity which he displayed, were almost entirely the results of the exertions of an unaided vigorous mind, as even the elementary acquirement of reading was only attained by him at the age of forty-five. In the earlier years of his government, Mehemet employed an old lady of his seraglio to read any writing of importance that came to him, and it was only when left without that confidential secretary by her death, that he had himself instructed in a knowledge of writing. DEATH OF JOHN PALMER, THE ACTOROnce now and then the stage has witnessed the death of some of its best ornaments in a very affecting way. This was especially so in the case of Mr. John Palmer, who, during the latter half of the last century, rose to high distinction as an actor, identifying himself with a greater variety of characters than any who had preceded him, except David Garrick. Palmer had a wife and eight children, and indulged in a style of living that kept him always on the verge of poverty. The death of his wife affected him deeply; and when, shortly afterwards, the death of a favourite son occurred, his system received a shock from which he never fully recovered. He was about that time, in 1798, performing at Liverpool. On the 2nd of August, it fell to his duty to perform the character of the Stranger, in Kotzebue's morbid play of the same name. He went through the first and second acts with his usual success; but during the third he became very much depressed in spirits. Among the incidents in the fourth act, Baron Steinfort obtains an interview with the Stranger, discovers that he is an old and valued friend, and entreats him to relate the history of his career-especially in relation to his (the Stranger's) moody exclusion from the world. Just as the children began to be spoken of, the man overcame the actor; poor Palmer trembled with agitation, his voice faltered; he fell down on the stage, breathed a convulsive sigh, and died. He had just before had to utter the words: Oh, God! oh, God! There is another and a better world! The audience, supposing that the intensity of his feeling had led him to acting a swoon, applauded the scene, though it was a painful one; but when the real truth was announced, a mournful dismay seized upon all. The above two lines were afterwards engraved on Palmer's tombstone, in Walton church-yard, near Liverpool. ANCIENT WRITING-MATERIALSSculptured records on stone are the earliest memorials of history we possess. When portable manuscripts became desirable, the skins of animals, the leaves or membraneous tissues of plants, even fragments of stone and tile, were all pressed into the service of the scribe. Notwithstanding the abundant and universal use of paper, some of these ancient utilities still serve modern necessities. Vellum is universally used for important legal documents, and many bibliomaniacs put them-selves and the printer to trouble and expense over vellum-printed copies of a favourite book. There is a peculiarly sacred tree grown in China, the leaves of which are used to portray sacred subjects and pious inscriptions upon; other eastern nations still make use of fibrous plants upon which to write, and sometimes to engrave, with a sharp finely-pointed implement, the words they desire to record. The ancient Egyptians wrote upon linen, or wood, with a brush or reed pen, but chiefly and commonly used the delicate membrane obtained by unrolling the fibrous stem of the papyrus; a water-plant once abundant, but now almost extinct in the Nile. Fragile as this material may at first thought appear, it is very enduring; European museums furnish abundant specimens of manuscripts executed in these delicate films three thousand years ago, that appear less changed than many do that were written with ordinary modern ink in the last century. It was usual with these early scribes to make use of fragments of stone and tile, upon which to write memorandums of small importance, or to cast up accounts; to use them, indeed, as we use 'scribbling paper.' The abundance of potsherds usually thrown in the streets of eastern towns, afforded a ready material for this purpose; and the mounds of antique fragments of tiles, &c., in the island of Elephantine, on the Nile, opposite Assouan (the extreme limit of ancient Egypt), has furnished more than a hundred specimens to our British museums, consisting chiefly of accountants' memoranda. The use of papyrus as a writing-material, descended to the Greeks and Romans. The thin concentric coats of this useful rush were carefully dried and pasted cross-ways over each other, to give firmness to the whole; the surface was then burnished smooth with a polishing stone, and written upon with a reed cut to a point similar to the modern pen. The ink was made from lamp-black or the cuttle-fish, like the Indian ink of our own era. Indeed, it is curious to reflect on the little change that occurs in articles of simple utility in the course of ages, and how slightly the terms have altered by which we distinguish them; thus the papyrus-reed gives the name to paper, and the roll or volume of manuscript is the origin of the term volume applied to a book. These rolls were packed away on the library shelves, and to one end was attached a label, telling of its contents. When the excavations at Pompeii were first conducted, many of these charred rolls were thought to be half-burned sticks, and disregarded; now, by very careful processes they are gradually unrolled, and have furnished us with very valuable additions to classic literature. Boxes of these rolls were carried from place to place as wanted, and representations of them, packed for the use of the student, are seen in the wall-paintings of Pompeii; they were cylindrical, with a cover (like a modern hat-box), and were slung by a strap across the shoulders. The Romans greatly advanced the convenience of the scribe, by the more general adoption of tablets of wood, metal, and ivory. These square tablets exactly resembled the slates now used in schools; having a raised frame, and a sunk centre for writing upon; which centre was coated with wax, and upon this an iron pen or stylus inscribed the writing; which was preserved from obliteration by the raised edge or frame when the tables were shut together. Hinges, or a string, could readily unite any quantity of these tablets, and form a very near approach to a modern volume. In excavating for the foundation of the Royal Exchange, in London, some of these tablets of the Roman era were found, and are now to be seen in the library at Guildhall.  The semi-barbaric nations that flourished after the fall of Rome, could do no better than follow the fashions set by the older masters of the world. A curious drawing in a fine manuscript, once the property of Charlemagne, and now preserved in the public library of the ancient city of Treves, on the Moselle, furnishes the annexed representation of a tabula held by a handle in the left hand of a scribe, exactly resembling the old horn-book of our village schools; the surface is covered with wax, partly inscribed by the metal style held in the right hand. These styli sometimes were surmounted by a knob, but frequently were beaten out into a broad, flat eraser, to press down the waxen surface for a new inscription. The style in our cut combines both. Useful as these tablets might be, their clumsiness was sufficiently apparent; books composed of vellum leaves superseded them soon after the Carlovingian era. The finest medieval manuscripts we possess, we owe to the unwearied assiduity of the clergy, whose 'learned leisure' was insured by monastic seclusion. Books that demanded a life-long labour to complete, were patiently worked upon, and often decorated with initial letters and ornament of the most gorgeous and elaborate kind. Enriched often by drawings, which give us living pictures of past manners, they are the most valuable relics of our ancestry, justly prized as the gems of our national libraries.  Attached to all large monasteries was a scriptorium, or apartment expressly devoted to the use of such persons as worked upon these coveted volumes. The scribes of the middle ages frequently carried their writing-materials appended to their girdles, consisting of an ink-pot, and a case for pens; the latter, usually formed of cuirboulli (leather softened by hot water, then impressed with ornament, and hardened by baking), which was strong as horn, of which latter material the ink-pot was generally formed. Hence the old term, 'ink-horn phrases,' for learned affectations in discourse. The incised brass to the memory of a notary of the time of Edward IV., in the church of St. Mary Key, at Ipswich, furnishes us with the excellent representation here given of a penner and ink-horn, slung across the man's girdle; they are held together by cords, which slip freely through loops at the side of each implement, the knob and tassel at each end preventing them from falling.  When book-learning was rare, and the greatest and wisest sovereigns, such as Charlemagne and our William, could do no more than make a mark as an autograph that now would shame a common peasant, the possession of knowledge gave an important position to a man, and granted him many immunities; hence was derived 'the benefit of clergy' as a plea against the punishment of crime; and the scraps of Latin a criminal was sometimes taught to repeat, was termed his neck-verse,' as it saved him from hanging. The printing press put all these notions aside, and a very general spread of knowledge broke down the exclusiveness of monastic life altogether. Books multiplied abundantly, and produced active thinking. The laborious process of producing them by hand-writing had gone for ever, and we take leave of this subject with a representation of the working - table of a scribe, contemporary with the invention of printing. The pages upon which he is at work lie upon the sloping desk; on the flat table above he has stuck his penknife; the pens lie on the standish in front of him. Bottles for ink of both colours are seen, and an hour-glass to give him due note of time. A pair of scissors, and a case for a glass to assist his eyes, are on the right side. This interesting group is copied from a picture in the gallery of the Museo Borbonico, at Naples. |