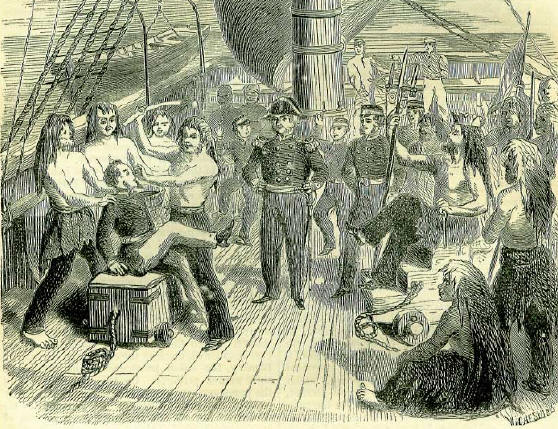

3rd DecemberBorn: Luigi Pulci, Italian poet, 1431, Florence; John Grater, eminent scholar and critic, 1560, Antwerp; Matthew Wren, bishop of Ely, 1585, London; Samuel Crompton, inventor of the mule for spinning cotton, 1753, Firwood, near Bolton; Robert Bloomfield, poet, 1766, Honington, Suffolk. Died: Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, distinguished commander, 1592; Giovanni Belzoni, explorer of Egyptian antiquities, 1823, Gate, in Guinea; John Flaxman, sculptor, 1826, London; Frederick VI, king of Denmark, 1839; Robert Montgomery, poet, 1855, Brighton; Christian Rauch, sculptor, 1857, Dresden. Feast Day: St. Lucius, king and confessor, end of second century. St. Birinus, bishop and confessor, 650. St. Sola, hermit, 790. St. Francis Xavier, Apostle of the Indies, confessor, 1552. SAMUEL CROMPTONMuslins, until near the close of last century, were all imported from India. English spinners were unable to produce yarn fine enough for the manufacture of such delicate fabrics. Richard Arkwright had invented spinning by rollers, and Hargreaves the spinning jenny, when, in 1779, Crompton succeeded in combining both inventions in his mule. He thereby enabled spinners to draw out long threads, in large numbers, to more than Hindu tenuity, and helped Lancashire effectually to her high and lucrative office of cotton-spinner-in-chief to the world. Samuel Crompton was born on the 3rd of December 1753, at Firwood, near Bolton. His father was a farmer, and the household, after the custom of Lancashire in those days, employed their leisure in carding, spinning, and weaving. While Samuel was a child, his father died. Shortly before his death, he had removed to a portion of an ancient mansion called Hall-in-the-Wood, about a mile from Bolton. It was a large rambling building, built in different styles and at different periods, and full of rooms, large and small, connected by intricate stairs and corridors. The picturesque site and appearance of Hall-in-the-Wood has made it a favourite subject with artists, and it has been painted and engraved again and again. Seldom Has a mechanical invention had a more romantic birthplace. Widow Crompton was a strong-minded woman, and carried on her husband's business with energy and thrift. She was noted for her excellent butter, honey, and elderberry wine. So high was her repute for management, that she was elected an overseer of the poor. Her boy Samuel she ruled straitly. He used to tell that she beat him occasionally, not for any fault, but because she so loved him. He received an ordinary education at a Bolton day-school, and when about sixteen, his mother set him to earn his living by spinning at home, and she exacted from him a certain amount of work daily. His youth at Hall-in-the-Wood was passed in comparative seclusion. All day he was alone at work, his mother doing the bargaining and fighting with the outer world. He was very fond of music, and managed to construct a violin, on which he learned to play with proficiency. His evenings he spent at a night-school in the study of mathematics. A virtuous, reserved, and industrious youth was Crompton's. At Hall-in-the-Wood lived his uncle, Alexander Crompton, a remarkable character. He was so lame that he could not leave the room in which he slept and worked. On his loom he wove fustians, by which he earned a comfortable living. Like the rest of the family, his piety was somewhat austere; and as he was unable to go to church, he was accustomed on Sundays, as soon as he heard the bells ringing, to put off his working -coat and put on his best. This done, he slowly read from the prayer-book the whole of the morning-service and a sermon, concluding about the same time as the church was coming out, when his good coat was laid aside, and the old one put on. In the evening, the same solitary solemnity was gone through. With one of Hargreaves's jennies, Crompton span. The yarn was soft, and was constantly breaking; and if the full quantity of allotted work was not done, Mrs. Crompton scolded, and the time lost in joining broken threads kept the gentle spinner from his books and his darling fiddle. Much annoyance of this kind drove his ingenuity into the contrivance of some improvements. Five years-from his twenty-first year, in 1774, to his twenty-sixth in 1779-were spent in the construction of the mule. 'My mind,' he relates, 'was in a continual endeavour to realise a more perfect principle of spinning; and though often baffled, I as often renewed the attempt, and at length succeeded to my utmost desire, at the expense of every shilling I had in the world.' He was, of course, only able to work at the mule in the leisure left after each day's task of spinning, and often in hours stolen from sleep. The purchase of tools and materials absorbed all his spare cash; and when the Bolton theatre was open, he was glad to earn eighteen-pence a night by playing the violin in the orchestra. The first mule was made, for the most part, of wood, and to a small roadside smithy he used to resort, 'to file his bits o' things.' Crompton proceeded very silently with his invention. Even the family at Hall-in-the-Wood knew little of what he was about, until his lights and noise, while at work in the night-time, excited their curiosity. Besides, inventors of machinery stood in great danger from popular indignation. The Blackburn spinners and weavers had driven Hargreaves from his home, and destroyed every jenny of more than twenty spindles for miles round. When this storm was raging, Crompton took his mule to pieces, and hid the various parts in a loft or garret near the clock in the old Hall. Meanwhile, he created much surprise in the market by the production of yarn, which, alike in fineness and firmness, surpassed any that had ever been seen. It immediately became the universal question in the trade, How does Crompton make that yarn? It was at once perceived that the greatly-desired muslins, brought all the way from the East Indies, might be woven at home, if only such yarn could be had in abundance. At this time Crompton married, and commenced housekeeping in a cottage near the Hall, but still retained his work-room in the old place. His wife was a first-rate spinner, and her expertness, it is said, first drew his attention to her. Orders for his fine yarn, at his own prices, poured in upon him; and though he and his young wife span their hardest, they were quite unable to meet a hundredth part of' the demand. Hall-in-the-Wood became besieged with manufacturers praying for supplies of the precious yarn, and burning with desire to penetrate the secret of its production. All kinds of stratagems were practised to obtain admission to the house. Some climbed up to the windows of the work-room, and peeped in. Crompton set up a screen to hide himself, but even that was not sufficient. One inquisitive adventurer is said to have hid himself for some days in the loft, and to have watched Crompton at work through a gimlet hole in the ceiling. If Crompton had only possessed a mere trifle of worldly experience, there is no reason why, at this juncture, he might not have made his fortune. Unhappily his seclusion and soft disposition placed him as a babe at the mercy of sharp and crafty traders. He discovered he could not keep his secret. 'A man,' he wrote, 'has a very insecure tenure of a property which another can carry away with his eyes. A few months reduced me to the cruel necessity either of destroying my machine altogether, or giving it to the public. To destroy it, I could not think of; to give up that for which I had laboured so long, was cruel. I had no patent, nor the means of purchasing one. In preference to destroying, I gave it to the public.' Many, perhaps the majority of inventors, have lacked the means to purchase a patent, bat have, after due inquiry, usually found some capitalist willing to provide the requisite funds. There seems no reason to doubt, that had Crompton had the sense to bestir himself, he could easily have found a friend to assist him in securing a patent for the mule, or the Hall-i'-th'-Wood-Wheel, as the people at first called it. He says he 'gave the mule to the public;' and virtually he did, but in such a way that he gained no credit for his generosity, and was put to inexpressible pain by the greed and meanness of those with whom he dealt. Persuaded to give up his secret, the following document was drawn up. We, whose names are hereunto subscribed, have agreed to give, and do hereby promise to pay unto, Samuel Crompton, at the Hall-in-the-Wood, near Bolton, the several sums opposite our names, as a reward for his improvement in spinning. Several of the principal tradesmen in Manchester, Bolton, &c., having seen his new machine, approve of it, and are of opinion that it would be of the greatest public utility to make it generally known, to which end a contribution is desired from every well-wisher of trade. To this were appended fifty-five subscribers of one guinea each, twenty-seven of half a guinea, one of seven shillings and sixpence, and one of five shillings and sixpence-making, together, the munificent sum of £67, 6s. 6d., or less than the cost of the model-mule which Crompton gave up to the subscribers! Never, certainly, was so much got for so little. The merciless transaction receives its last touch of infamy, from the fact recorded by Crompton in these words: Many subscribers would not pay the sums they had set opposite their names. When I applied for them, I got nothing but abusive language to drive me from them, which was easily done; for I never till then could think it possible that any man could pretend one thing and act the direct opposite. I then found it was possible, having had proof positive. Deprived of his reward, Crompton devoted himself steadily to business. He removed to Oldhams, a retired place, two miles to the north of Bolton, where he farmed several acres, kept three or four cows, and span in the upper story of his house. His yarn was the best and finest in the market, and brought the highest prices; and, as a consequence, he was plagued with visitors, who came prying about under the idea that he had effected some improvement in his invention. His servants were continually bribed away from him, in the hope that they might be able to reveal something that was worth knowing. Sir Robert Peel (the first baronet) visited him at Oldhams, and offered him a situation, with a large salary, and the prospect of a partnership; but Crompton had a morbid dislike to Peel, and he declined the overtures, which might have led to his lasting comfort and prosperity. In order to provide for his increasing family, he moved into Bolton in 1791, and enlarged his spinning operations. In 1800, some gentlemen in Manchester commenced a subscription on his behalf, but, what with the French war, the failure of crops, and suffering commerce, their kindly effort stuck fast between four and five hundred pounds. The amount collected was handed over to Crompton, who sunk it in the extension of his business. Aided by the mule, the cotton manufacture prodigiously-developed itself; but thirty years elapsed are any serious attempt was made to recompense the ingenuity and perseverance to which the increase was owing. At last, in 1812, it was resolved to bring Crompton's claims before parliament. It was proved that 4,600,000 spindles were at work on his mules, using up 40,000,000 lbs. of cotton annually; that 70,000 persons were engaged in spinning, and 150,000 more in weaving the yarn so spun; and that a population of full half a million derived their daily bread from the machinery his skill had devised. The case was clear, and Mr. Perceval, the chancellor of the exchequer, was ready to propose a handsome vote of money, when Crompton's usual ill-luck intervened in a most shocking manner. It was the afternoon of the 11th of May 1812, and Crompton was standing in the lobby of the House of Commons conversing with Sir Robert Peel and Mr. Blackburne, when one of them observed: 'Here comes Mr. Perceval.' The group was instantly joined by the chancellor of the exchequer, who addressed them with the remark: You will be glad to know that I mean to propose £20,000 for Crompton; do you think it will be satisfactory? Hearing this, Crompton moved off from motives of delicacy, and did not hear the reply. He was scarcely out of sight when the madman Bellingham came up, and shot Perceval dead. This frightful catastrophe lost Crompton £15,000. Six weeks intervened before his case could be brought before parliament, and then, on the 24th June, Lord Stanley moved that he should be awarded £5000, which the House voted without opposition. Twenty thousand pounds might have been had as easily, and no reason appears to have been given for the reduction of Mr. Perceval's proposal. All conversant with Crompton's merits felt the grant inadequate, whether measured by the intrinsic value of his service, or by the rate of rewards accorded by parliament to other inventors. With the £5000 Crompton entered into various manufacturing speculations with his sons; but none turned out well, and as he advanced in years some of his friends found it necessary to subscribe, and purchase him an annuity of £63. A second application to parliament on his behalf was instituted, but it came to nothing. Worn out with cares and disappointments, Crompton died at his house in King Street, Bolton, on the 26th of June 1827, at the age of seventy-four. The unhappiness of Crompton's life sprung from the absence of those faculties which enable a man to hold equal intercourse with his fellows. 'I found to my sorrow,' he writes, 'that I was not calculated to contend with men of the world; neither did I know there was such a thing as protection for me on earth!' When he attended the Manchester Exchange to sell his yams or muslins, and any rough-and-ready manufacturer ventured to offer him a less price than he had asked, he would invariably wrap up his samples, put them into his pocket, and quietly walk off. During a visit to Glasgow, the manufacturers invited him to a public dinner; but he was unable to muster courage to go through the ordeal, and, to use his own words, 'rather than face up, I first hid myself, and then fairly bolted from the city.' One day a foreign count called on him in Bolton. Crompton sent a message that he was in bed, and could not be seen. A friend, who accompanied the count, thereon ran up stairs, and proposed to Crompton that they should pay their visit in the bedroom; but he would not be persuaded, and vowed that if the count was brought up, he would hide under the bed! His excessive pride made him extremely sensitive to the very appearance of favour or patronage. To ask what was due to him always cost him acute pain. When in London, in 1812, prosecuting his claims, he wrote to Mr. Giddy, one of his most steadfast supporters in parliament, 'Be assured, sir, there will be no difficulty in getting rid of me. The only anxiety I now feel is, that parliament may not dishonour themselves. Me they cannot dishonour. All the risk is with them. I conceived it to be the greatest honour I can confer on them, to afford them an opportunity of doing me and themselves justice. I am certain my friends and family would be ashamed of me, were I to consider myself come here a-begging, or on the contrary demanding. I only request that the case may have a fair and candid hearing, and be dealt with according to its merits.' Crompton's habits were simple and frugal in the extreme, and by his industry he readily procured every comfort he cared to possess. Well would it have been for him when he lost the ownership of his invention, if he had been able to sweep every expectation connected with it into oblivion. The operation of these hopes were even less mischievous on him than on his sons and daughters, who unhappily were deprived of the guidance of their mother's good sense in their childhood. Before their eyes was continually dangling the possibility of their father being raised to affluence; and when poor Crompton came back to Bolton with £5000 instead of a great fortune, he heard the bitterest reproaches in his own household. His family he loved very tenderly, and we can fairly imagine that it was goaded by desire to satisfy them, that he spent five weary months in London in 1812, dancing attendance on members of parliament. Crompton has been described by those who knew him in the strength and beauty of manhood, as a singularly handsome and prepossessing man; all his limbs, and particularly his hands, were elegantly formed, and possessed great muscular power. He could easily lift a sack of flour by the head and tail, and pitch it over the side of a cart. His manners and motions were at all times guided by a natural politeness and grace, as far from servility as rudeness. His portrait displays a beautiful face and head, in which. none can fail to discern a philosopher and gentleman. Crompton's memory, until lately, has been strangely neglected. In 1859, Mr. Gilbert J. French, of Bolton, published an excellent biography of his townsman, from which work our facts have been drawn. A statue of Crompton, in bronze, by Mr. W. Calder Marshall, was erected in the market-place of Bolton in 1862. GIOVANNI BATTISTA BELZONIIn 1778, a son was born to a poor barber in the ancient city of Padua. There was little room for this novel addition to an impoverished family of fourteen, and the youth's earliest aspirations were to push his fortune far distant from his father's house. A translation of Robinson Crusoe falling into the lad's hands, excited an adventurous spirit, that clung to him through life; for, strange to say, Defoe's wonderful romance, though seemingly written with a view to deter and discourage wandering spirits, has ever had the contrary effect. When quite a boy, the barber's son ran away from home, but, after a few days' poverty, hardship, and weary travelling, he was fain to return to the shelter of the parental roof. He now settled for a season, learned his father's business, and, becoming an able practitioner with razor and scissors, he once more set off with the determination of improving his fortunes in the city of Rome. There a love disappointment induced him to enter a Capuchin convent, where he remained till the arrival of the French army threw the monks homeless and houseless on the world. Of an almost gigantic figure, and endowed with commensurate physical power, the barber-monk now endeavoured to support himself by exhibiting feats of strength and dexterity. The old inclination for wandering returning with increased force, he travelled through Germany to Holland and England, reaching this country in 1802. In the same year he performed at Sadler's Wells Theatre, in the character of the Patagonian Samson, as represented in the accompanying engraving, copied from a very rare character portrait of the day. His performance is thus described in a contemporary periodical: Signor Belzoni's performance consists in carrying from seven to ten men in a manner never attempted by any but himself. He clasps round him a belt, to which are affixed ledges to support the men, who cling round him; and first takes up one under each arm, receives one on either side, one on each of his shoulders, and one on his back; the whole forming a kind of a pyramid. When thus encumbered, he moves as easy and graceful as if about to walk a minuet, and displays a flag in as flippant a manner, as a dancer on the rope. In some unpublished notes of Ellar, the Harlequin and contemporary of Grimaldi, the pantomimist observes that he saw Belzoni in 1808, performing in Sander's Booth, at Bartholomew Fair, in the character of the French Hercules. In 1809, he continues: Belzoni and I were jointly engaged at the Crow Street Theatre, Dublin, in the production of a pantomime-I as Harlequin, he as artist to superintend the last scene, a sort of hydraulic temple, that, owing to what is frequently the case, the being overanxious, failed, and nearly inundated the orchestra. Fiddlers generally follow their leader, and Tom Cook, now leader at Drury Lane, was the man; out they ran, leaving Columbine and myself, with the rest, to finish the scene in the midst of a splendid shower of fire and water. The young lady who played the part of Columbine was of great beauty, and is now the wife of the celebrated Thomas Moore, the poet. Signor Belzoni was a man of gentlemanly but very unassuming manners, yet of great mind. There are few towns in England, Scotland, or Ireland in which Belzoni did not exhibit about this period. The following is an exact copy of one of his hand-bills, issued in Cork early in 1812. The GRAND CASCADE, mentioned in the bill, was in all probability the splendid shower of fire and water recorded in the preceding passage from Ellar's note-book. Theatre,Patrick Street. CUT A Man's Head Off!!! AND PUT IT ON AGAIN! This present Evening MONDAY, Feb. 24, 1812, And positively and definitively the LAST NIGHT SIG. BELZONI RESPECTFULLY acquaints the Public, that by the request of his Friends, he will Re-open the above Theatre for one night more-i. e., on MONDAY Feb. 24, and although it has been announced in former Advertisements, that he would perform for Two Nights -he pledges his word that this present Evening, will be positively and definitively the last night of his Re-presentations, and when he will introduce a FEAT OF LEGERDEMAIN, which he flatters himself will astonish the Spectators, as such a feat never was attempted in Great Britain or Ireland. After a number of Entertainments, he will CUT A Man's Head 0ff! And put it on Again!!! ALSO THE GRAND CASCADE. Belzoni married in Ireland, and continuing his wandering life, exhibited in France, Spain, and Italy. Realizing a small capital by his unceasing industry, he determined to visit Egypt, a country that for ages has been the El Dorado of the Italian race. Belzoni's object in visiting Egypt was to make a fortune by instructing the natives to raise water, by a very dangerous method, now abandoned-a kind of tread-wheel, formerly known to English mechanics by the technical appellation of 'the monkey.' Being unsuccessful in this endeavour, he turned his attention to removing some of the ancient Egyptian works of art, under the advice and patronage of Mr. Salt, the British consul. The various adventures he went through, and how he ultimately succeeded, are all detailed by Belzoni in the published account of his travels, entitled Narrative of the Operations and recent Discoveries in the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs, and Cities of Egypt and Nubia. Scarcely four years' exertions in Egypt had made Belzoni comparatively wealthy and famous. On his way to England, to publish his book, he visited Padua, and was received with princely honours. The authorities met him at the city gates, presented him with an address, and ordered a medal to be struck in his honour. Arriving in London, he became the fashionable lion of the day; and with a pardonable reticence, Belzoni took care not to allude to the character he had formerly sustained when in England. On this point the late Mr. Crofton Croker tells an interesting story, published in Willis's Current Notes. He says: I remember meeting Belzoni, the last day of 1821, at the late Mr. Murray's, in Albemarle Street, where we saw the New Year in, and 'glorious John' brewed a special bowl of punch, for the occasion. Beside the juvenile family of our host, the whole D'Israeli family were present. We all played a merry game of Pope Joan, and when that was over, Murray presented to each a pocket-book, as a New-year's gift. Murray was engaged, at a side-table, making the punch, upon tasting the excellence of which he uttered something like the sounds made by a puppet-showman, when about to collect an audience. The elder D'Israeli thereupon took up my pocket-book, and wrote with his pencil the following impromptu: Gigantic Belzoni at Pope Joan and tea, What a group of mere puppets, we seem beside thee; Which our kind host perceiving, with infinite jest, Gives us Punch at our supper, to keep up the jest. Indifferent as the epigram itself was, I smiled at it, and observed: 'Very true-excellent!' Which Belzoni perceiving, said: 'Will you permit me to partake of your enjoyment?' 'Certainly,' I replied, handing him the book. Never shall I forget his countenance after he had read the four lines. He read the last line twice over, and then his eyes actually flashed fire. He struck his forehead, and muttering: 'I am betrayed! ' abruptly left the room At a subsequent interview between Mr. Croker and Belzoni, the latter accounted for his strange conduct by stating that he had considered the lines to be an insulting allusion to his early life as a show-man. On Mr. Croker explaining that they could not possibly have any reference to Min, Belzoni requested the former to accompany him to Mr. Murray, with the view of making an explanation. They went, and then the great publisher knew, for the first time, that the celebrated Egyptian explorer had been an itinerant exhibitor. The active mind of Belzoni soon tired of a mere London existence. In 1822, he determined to embark in the too fatal field of African adventure. In the following year, when passing from Benin to Houssa, on his way to Timbuctoo, he was stricken with dysentery, carried back to Gato, and put on board an English vessel lying off the coast, in hopes of receiving benefit from the sea-air. He there died, carefully attended by English friends, to whom he gave his amethyst ring, to be delivered to his wife, with his tender affection and regrets that he was too weak to write his last adieux. The kindly sailors, among whom he died, carried his body ashore, and buried it under an arsamatree, erecting a monument with the following inscription: HERE LIE THE REMAINS OF G. BELZONI, Esq. Who was attacked with dysentery on the 20th Nov. at Benin, on his way to Houssa and Timbuctoo, and died at this place on the 3rd December 1823. 'The gentlemen who placed this inscription over the remains of this celebrated and intrepid traveller, hope that every European visiting this spot, will cause the ground to be cleared and the fence around repaired if necessary. The people of Padua have since erected a statue to the memory of their townsman, the energetic son of a poor barber; but it was not till long after his death that the government of England bestowed a small pension on the widow of Belzoni. 'CROSSING THE LINE'Among the festivals of the old Roman calendar, in pagan times, we find one celebrated on the 3rd of December, in honour of Neptune and Minerva. In connection with the former of these deities, we may here appropriately introduce the account of a well-known custom, which, till recently, prevailed on board ship, and was regarded as specially under the supervision of Neptune, who, in propriâ, was supposed to act the principal part in the ceremony in question. We refer to the grand marine saturnalia which used to be performed when crossing the line:' that is, when passing from north to south latitude, or vice versâ. The custom, in some form or other, is believed to be very ancient, and to have been originally instituted on the occasion of ships passing out of the Mediterranean into the Atlantic, beyond the 'Pillars of Hercules.' It had much more absurdity than vice about it; but sometimes it became both insulting and cruel. When the victims made no resistance, and yielded as cheerfully as they could to the whim of the sailors, the ceremony was performed somewhat in the following way, as related by Captain Edward Hall, and quoted by Hone: The best executed of these ceremonies I ever saw, was on board a ship of the line, of which I was lieutenant, bound to the West Indies. On crossing the line, a voice, as if at a distance, and at the surface of the water, cried: 'Ho, ship ahoy! I shall come on board!' This was from a person slung over the bows, near the water, speaking through his hands. Presently two men of large stature came over the bows. They had hideous masks on. One represented Neptune. He was naked to the waist, crowned with the head of a large wet swab, the end of which reached to his loins, to represent flowing locks; a piece of tarpaulin, vandyked, encircled the head of the swab and his brows as a diadem; his right hand wielded a boarding-pike, manufactured into a trident; and his body was smeared with red ochre, to represent fish-scales. The other sailor represented Amphitrite, having locks formed of swabs, a petticoat of the same material, with a girdle of red bunting; and in her hand a comb and looking-glass. They were followed by about twenty fellows, naked to the waist, with red ochre scales, as Tritons. They were received on the forecastle with much respect by the old sailors, who had provided the carriage of an eighteen-pounder gun as a car, which their majesties ascended: and were drawn aft along the gangway to the quarter-deck by the sailors. Neptune, addressing the captain, said he was happy to see him again that way; adding that he believed there were some 'Johnny Raws' on board who had not paid their dues, and whom he intended to initiate into the salt-water mysteries. The captain answered, that he was happy to see him, but requested he would make no more confusion than was necessary. They then descended to the main-deck, and were joined by all the old hands, and about twenty ' barbers,' who submitted the shaving-tackle to inspection.' This shaving tackle consisted of pieces of rusty hoop for razors, and very unsavoury compounds as shaving-soap and shaving-water, with which the luckless victim was bedaubed and soused. If he bore it well, he was sometimes permitted to join in per-forming the ceremony upon other 'Johnny Raws.'  It was not always, however, that neophytes conformed without resistance to such rough christening ceremonies. A legal action, instituted in 1802, took its rise from the following circumstances. When the ship Soleby Castle was, in the year mentioned, crossing the equator on the way to Bombay, the sailors proceeded to the exercise of their wonted privilege. On this occasion, one of the passengers on board, Lieutenant Shaw, firmly resisted the performance of the ceremony. He offered to buy off the indignity by a present of money or spirits; but this was refused by the men, and it then became a contest of one against many. Shaw shut himself up in his cabin, the door of which he barricaded with trunks and boxes; and he also barred the port or small window. After he had remained some time in this voluntary imprisonment, without light or air, during the hottest part of the day, and 'under the line,' the crew, dressed as Neptune and his satellites, came thundering at his cabin-door, and with oaths and imprecations demanded admission. This he refused, but at the same time renewed his offer of a compromise. Mr. Patterson, the fourth mate, entreated the crew, but in vain, to accept the offer made to them. The men, becoming chafed with the opposition, resolved now to obtain their way by force, regardless of consequences. They tried to force the door, but failed. Mr. Raymond, third mate, sanctioned and approved the conduct of the men; and suggested that while some were engaged in wrenching the door off its hinges, others should effect an entry through the port. A sailor, armed with a sword and bludgeon, was lowered by a rope down the outside of the ship; and he succeeded in getting into the cabin, just at the moment when the other sailors forced open the door. Lieutenant Shaw defended himself for a time with his sword, and fired off his pistols-more for the sake of summoning assistance than to do injury, for they were not loaded. The whole gang now pressed round him, and after wresting the sword from his hand, dragged him upon deck. There he clung for some time to the post of the Cuddy-door; and, finding the first and third mates to be abetting the seamen, he called out loudly for the captain. The captain's cabin-door, however, was shut, and he either did not or would not hear the appeal. So impressed was the sensitive mind of the lieutenant with the indignity in store for him, that he actually endeavoured to throw himself overboard, but this was prevented by Mr. Patterson. Unmoved by all his entreaties, the crew proceeded with the frolic on which they had set their hearts, and which, after the resistance they had encountered, they resolved not to forego on any terms. They seized the lieutenant, dragged him along the quarter-deck to the middle of the ship, and placed him sitting in a boat half-filled with filthy liquid. His eyes being bandaged with a dirty napkin, a nauseous composition of tar and pitch was rubbed over his face, as 'Neptune's shaving soap,' and scraped off again by means of a rusty hoop, which constituted 'Neptune's razor.' He was then pushed back with violence into the boat, and there held struggling for some seconds, with his head immersed in the noisome liquid. Injured in body by this rough treatment, he was much more wounded in his mental feelings; and when the ship arrived at Bombay, he brought an action against the first and third mates. The fourth mate bore witness in his favour; and the captain, as a witness, declared that he did not hear the cry for assistance; but it is known that captains, at that time, were mostly unwilling to interfere with the sailors on such occasions. The damages of 400 rupees (£40), though more than the mates relished being called upon to pay, could scarcely be deemed a very satisfactory recompense for the inflictions which the lieutenant had undergone. The improvement wrought among seafaring-men during the last few years, has tended to lessen very much the frequency of this custom. Not only naval officers, but officers in the mercantile marine, are better educated than those who filled such posts in former times; and the general progress of refinement has led them to encourage more rational sports among the crew. The sailors themselves are not much more educated than formerly; but improvement is visible even here; and the spirit which delighted in the coarse fun of this equatorial shaving,' is now decidedly on the wane. |