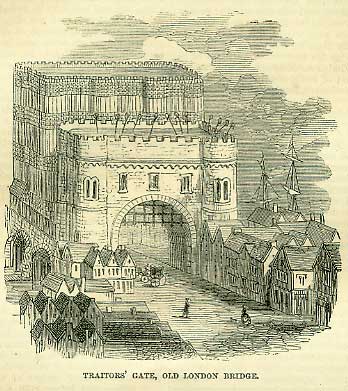

1st AugustBorn: Tiberius Claudius Drusus, Roman emperor, uncle and successor of Caligula, B.C. 11, Lyons. Died: Marcus Ulpius Trajanus Crinitus (Trojan), Roman emperor, 117, Minus, in Cilicia; Pope Celestine I, 432; Louis VI, surnamed he Gros, king of France, 1137; Stephen Marcel, insurrectionary leader, slain at Paris, 1358; Cosmo de Medici, the elder, grandfather of Lorenzo the Magnificent, 1464, Florence; Lorenzo Valla, distinguished Latin scholar, 1457 or 1465, Rome; Anne, queen of England, 1714; Jacques Boileau, theologian, brother of the satirist, 1716, Paris; Admiral Sir John Leake, great naval commander, 1720, Greenwich; Richard Savage, poet and friend of Johnson, 1743, Bristol; Bernard Siegfried Albinus, celebrated anatomist, 1770, Leyden; Dr. Shebbcare, notorious political writer, 1788; Mrs. Elizabeth Inchbald, actress and dramatist, 1821; Rev. Robert Morrison, D.D., first Protestant missionary to China, 1834, Canton; Harriet Lee, novelist, 1851, Clifton; Bayle St. John, miscellaneous writer, 1859, London. Feast Day: St. Peter ad Vincula, or St. Peter's Chains. The Seven Machabees, brothers, and their mother, martyrs. Saints Faith, Hope, and Charity, virgins and martyrs, 2nd century. St. Pellegrini or Peregrinus, hermit, 643. St. Ethelwold, bishop of Winchester, confessor, 984. LAMMASThis was one of the four great pagan festivals of Britain, the others being on 1st November, 1st February, and 1st May. The festival of the Gule of August, as it was called, probably celebrated the realisation of the first-fruits of the earth, and more particularly that of the grain-harvest. When Christianity was introduced, the day continued to be observed as a festival on these grounds, and, from a loaf being the usual offering at church, the service, and consequently the day, came to be called Half-mass, subsequently shortened into Lammas, just as hlaf-dig (bread-dispenser), applicable to the mistress of a house, came to be softened into the familiar and extensively used term, lady. This we would call the rational definition of the word Lammas. There is another, but in our opinion utterly inadmissible derivation, pointing to the custom of bringing a lamb on this day, as an offering to the cathedral church of York. Without doubt, this custom, which was purely local, would take its rise with reference to the term Lammas, after the true original signification of that word had been forgotten. It was once customary in England, in contravention of the proverb, that a cat in mittens catches no mice, to give money to servants on Lammas-day, to buy gloves; hence the term Glove-Silver. It is mentioned among the ancient customs of the abbey of St. Edmund's, in which the clerk of the cellarer had 2d.; the cellarer's squire, 11d.; the granger, 11d.; and the cowherd a penny. Anciently, too, it was customary for every family to give annually to the pope on this day one penny, which was thence called Denarius Sancti Petri, or Peter's Penny.'-Hampson's Medii AEvi Kalendarium. What appears as a relic of the ancient pagan festival of the Gule of August, was practised in Lothian till about the middle of the eighteenth century. From the unenclosed state of the country, the tending of cattle then employed a great number of hands, and the cow-boys, being more than half idle, were much disposed to unite in seeking and creating amusement. In each little district, a group of them built, against Lammas-day, a tower of stones and sods in some conspicuous place. On Lammas-morning, they assembled here, bearing flags, and blowing cow-horns-breakfasted together on bread and cheese, or other provisions-then set out on a march or procession, which usually ended in a foot-race for some trifling prize. The most remarkable feature of these rustic fetes was a practice of each party trying, before or on the day, to demolish the sod fortalice of some other party near by. This, of course, led to great fights and brawls, in which blood was occasionally spilt. But, on the whole, the Lammas Festival of Lothian was a pleasant affair, characteristic of an age which, with less to gain, had perhaps rather more to enjoy than the present COSMO DE MEDICISThe Florentine family of the Medicis, which made itself in various ways so notable in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries, may be said to have been founded by Cosmo, who died in 1464. This gentleman, for he was of no higher rank, by commerce acquired wealth comparable to that of kings, which enabled him to be the friend of the poor, to enrich his friends, to ornament his native city with superb edifices, and to call to Florence the Greek savans chased out of Constantinople. His counsels were, during thirty years, the laws of the republic, and his benefactions its sole intrigues. Florence, by common consent, inscribed his tomb with the noble legend: 'THE FATHER OF HIS COUNTRY.' MRS. INCHBALDBiography does not perhaps afford a finer example of industry, prudence, self-denial, and beneficence, than the story of Mrs. Inchbald. Starting in life with the merest rudiments of education, she managed to make a living in literature; her personal expenditure she governed with a severity which Franklin's 'Poor Richard' might have applauded; her charity she dispensed with a lavish generosity; her path lay through scenes proverbial for their dangers, yet she preserved a spotless name; and the world's copious flattery of her beauty and abilities-an intoxication which but few of the strongest heads can wholly withstand-left the even tenor of her conduct unaffected. It was not that she was a block of indifference; she was a woman of warm affections and delicate sensibilities; but a lively common-sense, cultivated by much experience in the hard school of adversity, ruled supreme in her mind, and when success and honour fell to her lot, she stood proof to all their wiles. Elizabeth Inchbald was the daughter of Simpson, a Suffolk farmer, and was born at Standingfield, near Bury St. Edmunds, on the 15th of October 1753. She very early took a fancy for the stage, and when about eighteen, she eloped from her mother's care, and made her way to London in search of an engagement as an actress. After sundry perilous adventures among the theatres, she married, in 1772, Mr. Inchbald, a second-rate actor, twice her own age. With him she strolled for seven years from city to city of the three kingdoms, sometimes in the enjoyment of plenty, and some-times in such poverty that they were glad to make a dinner by the roadside out of a turnip-field. In 1779, Mr. Inchbald died suddenly at Leeds, leaving his young widow with funds in hand to the amount of £350. She started for London, and was engaged at Covent Garden for 26s. 8d. a week, and subsequently by Colman at the Haymarket for 30s. Whilst acting for Colman in 1784, she took it into her head to write a farce, The Mogul Tale, which not only pleased the town, but drew from Colman the grateful assurance that, as a dramatist, she might earn as much money as she wanted. Thus encouraged, she went on writing play after play to the number of about a score, and for some of which she received large sums. Every One has His Fault brought her £700, and To Marry or Not to Marry, £600. She was a favourite performer, but she owed her popularity more to her piquant beauty than to her histrionic powers. She had, moreover, an impediment in her speech, which only with great difficulty she could conceal. Having there-fore discovered an easier means of livelihood, she retired from the stage in 1789. She next tried her hand as a novelist, and in 1791, published. A Simple Story, and in 1796, Nature and Art, which carried her fame into regions where her dramas were unknown. Respected by all, and loved by those who intimately knew her, she died in Kensington on the 1st of August 1821, leaving a little fortune in the funds which had been yielding her £260 a year. Mrs. Inchbald's relations were poor, and some unfortunate, and she ministered to their necessities with a liberality which, measured by her income, was really extraordinary. To a widowed sister, Mrs. Hunt, she allowed a pension of .£100 a year. To meet such sacrifices, she pinched herself to a degree that would have done credit to a saint of the Catholic church, to which church, by birth and conviction, she belonged. On the death of Mrs. Hunt, she wrote to a friend: 'Many a time this winter, when I cried with cold, I said to myself-but, thank God, my sister has not to stir from her room: she has her fire lighted every morning; all her provisions bought, and brought to her ready cooked: she would be less able to bear what I bear; and how much more should. I have to suffer but for this reflection! It almost made me warm when I thought that she suffered no cold.' To save money for the use of others, she lived in cheap lodgings, migrating from one neighbourhood to another, in the hope of discomforts as amusing as pitiful. With a milliner in the Strand she stayed some years, and she thus depicts the accommodation she enjoyed: 'My present apartment is so small, that I am all over black and blue with thumping my body and limbs against my furniture on every side; but, then, I have not far to walk to reach anything I want, for I can kindle my fire as I lie in bed, and put on my cap as I dine, for the looking-glass is obliged to stand on the same table with my dinner. To be sure, if there was a fire in the night, I must inevitably be burned, for I am at the top of the house, and so removed from the front part of it, that I cannot hear the least sound of anything from the street; but, then, I have a great deal of fresh air, more daylight than most people in London, and the enchanting view of the Thames and the Surrey Hills.' She was accustomed to wait on herself and clean out her room, as the following passage from one of her letters will prove: 'I have been very ill indeed, and looked worse than I was; but since the weather has permitted me to leave off making my fire, scouring the grate, sifting the cinders, and all the et cetera of going up and down three pair of long stairs with water and dirt, I feel quite another creature.' And again: 'Last Thursday morning, I finished scouring my bed-chamber, while a coach with a coronet and two footmen waited at the door to take me an airing.' Money, so precious to her, she was able to decline when its purchase was at the cost of good taste. She had written her Memoirs, and twice was offered. £1000 for the manuscript; but it seemed to her that its publication would cause suffering and irritation, and she took counsel with her spiritual adviser. Her diary thus records her heroic decision: 'Query. What I should wish done at the instant of death? Dr. Pointer. Do it now. Four volumes destroyed.' Mrs. Inchbald was rather tall, and of a striking figure. She was fair, slightly freckled, and her hair of a sandy-auburn hue. Her face was lovely, and full of spirit and sweetness. ' Her dress,' records one of her admirers, 'was always becoming, and very seldom worth so much as eightpence.' She had many suitors, young, rich, and noble, but none among them did she care to accept. She fell in love with her physician, Dr. Warren, but he was a married man; and whilst, like a true woman, she suppressed her feelings, she sometimes yielded so far as to pace Sackville Street at night, for the pleasure of seeing the light in his window. With all her prudence she was frank in speech, and loved gaiety and frolic. Here is what Leigh Hunt calls 'a delicious memorandum' from her diary: 'On Sunday, dined, drank tea, and supped with Mrs. Whitfield. At dark, she, and I, and her son William walked out; and I rapped at doors in New Street and King Street, and ran away.' This was in 1788, when she was five-and-thirty. 'But,' says Leigh Hunt, 'such people never grow old. Imagine what the tenants would have thought, could anybody have told them that the runaway-knocks were given by one of the most respectable of women-a lady midway between thirty and forty, and authoress of the Simple Story!' GREAT FIRES A CAUSE OF RAIN: ESPY'S THEORYThere is extant a letter, dated the 1st of August 1636, from the Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery to the high-sheriff of Staffordshire, stating that the king was about to pass through that county, and having heard there was an opinion in it that the burning of fern brought down rain, he desired that such practice should be forborne for the time, 'that the country and himself may enjoy fair weather as long as he remains in those parts.' In Scotland, it is customary in spring to burn large tracts of heather, in order that herbage may grow in its place; and there also it is a common remark that the moor-burn, as it is called, generally brings rain. The idea looks very like a piece of mere folklore, devoid of a foundation in truth; but it is very remarkable that, in our own age, a scientific American announced a theory involving this amongst other conclusions, that extensive fires on the surface of the earth were apt to produce rainy weather. He was a simple-hearted man, named James P. Espy, who for many years before his death in 1860 had occupied a post under the American government at Washington. It is undoubted that he made an immense collection of facts in support of his views, and though most of his scientific friends thought he was too ready to adopt conclusions, and too little disposed to review and test them, yet it must be admitted that his law of storms,' as he called it, was entitled to some measure of consideration. It may be thus briefly stated: When a body passes from a solid to a fluid state, it absorbs a large amount of caloric. In passing from a liquid to a solid state, this caloric of fluidity is given out. In the same manner liquids passing into vapour absorb, and vapours condensed to liquids give out the caloric of elasticity. The former is 140°, the latter no less than 103°. The evaporation of water cools the earth, by its absorption of this caloric of elasticity. The condensation of vapour into clouds sets free this latent caloric, which rarefies the surrounding atmosphere, and produces an upward current of air. When the atmosphere is well charged with vapour, an ascending current, however produced, causes condensation, by exposing the vapour to cold. This condensation, setting free latent caloric, produces a further upward movement and condensation. The air rushes in on every side to fill the partial vacuum. This air takes the upward movement, with the accompanying phenomena of condensation and the attendant rarefaction, until the clouds so formed are precipitated in rain; or where the movement is more powerful, in hail, sometimes accompanied by water-spouts and tornadoes. All storms, Mr. Espy held, have these characteristics. There is a central upward movement, with condensation of vapour, forming clouds. The wind blows from every side toward the centre. When the movement is very powerful, in level countries and hot climates, it has the character of a tornado, in the track of which he always found trees fallen in every direction, but always toward the centre. The water-spout forms the centre of the tornado at sea. The formation of hail has long puzzled men of science. Why should drops of water, falling from a cloud, be frozen while passing through a still warmer atmosphere, and even in hot climates? Mr. Espy's upward current solves the difficulty. The rain-drops are first carried up into the region of congelation, and being thrown outward, fall to the earth. So great masses of water, carried up in water-spouts, fall in a frozen state, in lumps which have sometimes measured fifteen inches in circumference. In the same manner Mr. Espy accounts for the occasional raining of frogs, fishes, sand, seeds, and stranger substances; but he does not account for such matters being kept in the clouds for several days, and carried over hundreds of miles' distance from the place where they were carried up in tornado or water-spout. They may have been carried up by the force of aërial currents, but it does not appear that they could be kept up for any length of time by such currents. Thousands of tons of water are swept into the clouds by water-spouts, but what power prevents it from pouring down again in torrents? Still the theory of Mr. Espy is very ingenious, and has the merit of affording a reasonable explanation to many, if not all, phenomena. The committee of the French Academy called his attention to the connection of electricity with meteoric phenomena, but he does not appear to have pursued that branch of investigation. It is our opinion that a certain electrical condition of bodies in the atmosphere gives them a repulsion to the earth, and that gravitation has no effect upon such bodies, until there is a change in their electrical condition. The earth is a magnet which may either attract or repel bodies, as they are positive or negative to it. Only in this, or in some such way, can we account for solid bodies, often of considerable density, being sustained for days in the atmosphere. It may be admitted, in conformity with Mr. Espy's theory, that such bodies may have been carried upward in a tornado, and it may be that the atmospheric movements may develop their electrical condition. It was to these matters, doubtless, that the French Academy wished to direct his attention. Mr. Espy was very anxious that the American government should make appropriations to test the utility of a practical application of his theory. He always asserted that, in a certain condition of the atmosphere, as of a high dew-point in a season of drouth, it was practicable to make it rain by artificial means. Nothing was necessary but to make an immense fire. This would produce an upward current, vapour would condense, the upward movement would thereby be increased, currents of air would flow in, with more condensation, until clouds and rain would spread over a great surface of country, so that for a few thousands of dollars a rain would fall worth millions. Mr. Espy had observed that the burning of forests and prairies in America is often followed by rain. He believed that the frequent showers in London and other large cities have a similar origin. Rains have even been supposed to be caused by great battles. There is little doubt that they are caused by volcanic eruptions. An eruption in Iceland has been followed by rains over all Europe. In 1815, during an eruption of a volcano in one of the East India Islands, of a population of 12,000, all but 26 were killed by a series of terrific tornadoes. In this case there were phenomena strongly corroborative of Mr. Espy's theory. Large trees, torn up by the tornadoes, appear to have been carried upward by an ascending current formed first by the heat of the volcano, and then by the rush of winds from every quarter, for these trees, after being carried up to a vast height, were thrown out-ward and descended, scorched by the volcanic fires. INSTITUTION OF THE ORDER OF St. MICHAEL AUGUST 1, 1469There had been an order of the Star in France, but it had fallen into oblivion. When Louis XI resolved that it was necessary there should be an order of knighthood in his kingdom, he reflected that it was easier to create a new, than to revive the lustre of an old one. As to a name for his proposed fraternity, there was no being of reality held in greater esteem in that age than the archangel Michael. It was believed that this celestial person-age had fought visibly for the French at Orleans. The superstitious king worshipped him probably more vehemently than he did his God. Accordingly, he chose for his new order the name of St. Michael. The knights, thirty-six in number, all men of name and of birth, could only be degraded for three crimes-heresy, treason, and cowardice. THOMAS DOGGET AND THE WATERMEN'S ROWING-MATCHAnnually, on the 1st of August, there takes place one of the great rowing matches, or races, on the Thames. The competitors are six young watermen, whose apprenticeship ends in the same year-the prize, a waterman's coat and silver badge. The distance rowed extends from the Old Swan at London Bridge, to the White Swan at Chelsea, against an adverse tide; so none but men of great strength, skill, and endurance need attempt the arduous struggle. The prize, though not of much intrinsic value, may be termed the Red Ribbon of the river, being an important step towards the grand Cordon Bleu-the championship of the Thames. The founder of this annual contest was one Thomas Dogget, a native of Dublin, and a very popular actor in the early part of the eighteenth century. He is described as ' a little, lively, spract man, who danced the Cheshire Rounds full as well as the famous Captain George, but with more nature and nimbleness.' Tony Aston, in the rarest of theatrical pamphlets, tells us that he travelled with Dogget when the latter was manager of a strolling-company, and he gives a very different idea of a stroller's life, as it was then, from that generally entertained. Each member of the company wore a brocaded waistcoat, kept his own horse, on which he rode from town to town, and was everywhere respected as a gentleman-seemingly better off than even those in the old ballad quoted by Hamlet, when he says: 'Then came each actor on his ass.' Colley Cibber describes Dogget as the most original and the strictest observer of nature of all his contemporaries. He borrowed from none, though he was imitated by many. In dressing a character to the greatest exactness, he was remark-ably skilful; the least article of whatever habit hewore, seemed in some degree to speak and mark the different humour he represented. He could be extremely ridiculous without stepping into the least impropriety, and knew exactly when and where to stop the current of his jokes. He could, with great exactness, paint his face to resemble any age from manhood to extreme senility, which caused Sir Godfrey Kr-teller to say that Dogget excelled him in his own art; for he could only copy nature from the originals before him, while the actor could vary them at pleasure, and yet always preserve a true resemblance. Dogget was an ardent politician, and an enthusiastic advocate of the Hanoverian succession. It was in honour of this event that he gave a water-man's coat and badge to be rowed for on the first anniversary of the accession of the First George to the British throne. And at his death he bequeathed a sum of money, the interest of which was to be appropriated annually, for ever, to the purchase of a like coat and badge, to be rowed for on the 1st of August, in honour of the day. And with the minute attention to matters of dress which distinguished him as an actor, and in accordance with his political principles, he directed that the coat should be of an orange colour, and the badge should represent the white horse of Hanover. Almost as we write, on the 12th of February 1863, the Prince of Wales visits the worshipful company of Fishmongers, in their own magnificent hall at London Bridge. And a newspaper paragraph, describing the festival, says, ' With singular appropriateness and good taste, eighteen watermen, who had at various periods, since the year 1824, been winners of Dogget's coat and badge, arrayed in the garb which testifies to their prowess, and of which the Fishmongers' Company are trustees, were substituted for the usual military guard of honour in the vestibule.' A more stalwart set of fellows, in more quaintly antique costume, could scarcely be found in any country, to serve as an honorary guard on 'the expectancy and rose of the fair state.' LONDON BRIDGE-NEW AND OLDOn the day when William IV and Queen Adelaide opened New London Bridge (August 1, 1831), the vitality of the old bridge may be said to have ceased; a bridge which had had more commerce under and over it perhaps than any other in the world. Eight centuries at least had elapsed since the commencement of that bridge-traffic. There were three or four bridges of wood successively built at this spot before 1176 A.D., in which year the stone structure was commenced; and this was the veritable 'Old London Bridge,' which served the citizens for more than six hundred and fifty years. A curious fabric it was, containing an immense quantity of stone arches of various shapes and sizes, piers so bulky as to render the navigation between them very dangerous, and (until 1754) a row of buildings a-top. The bridge suffered by fire in 1212, again in 1666, and again in 1683. So many were the evils which accumulated upon, around, and under it, that a new bridge was resolved upon in 1823 -against strong opposition on the part of the corporation. John Rennie furnished the plans, and his son, Sir John, carried them out. The foundation-stone was laid in 1825 by the Duke of York and the lord mayor; and the bridge took six years in building. The cost, with the approaches at both ends, was not less than two millions sterling, and was defrayed by a particular application of the coal-tax. The ceremonial attending the opening, on the 1st of August 1831, comprised the usual routine of flags, music, procession, addresses, speeches, &c. The old bridge finally disappeared towards the end of 1832; and then began in earnest the career of that noble structure, the new bridge, which. is now crossed every day by a number of persons equal to the whole population of some of our largest manufacturing towns. Strictly, the Old London Bridge, for a water-way of 900 feet, had eighteen solid stone piers, varying from 25 to 34 feet in thickness; thus confining the flow of the river within less than half its natural channel. That this arose simply from bad engineering, is very probable; but it admitted of huge blocks of building being placed on the bridge, with only a few inter-spaces, from one end to the other. These formed houses of four stories in height, spanning across the passage-way for traffic, most of which was, of course, as dark as a railway - tunnel. Nestling about the basement-floors of these buildings were shops, some of which, as we learn from old title-pages, were devoted to the business of bookselling and publishing. It is obvious that the inhabitants of these dwellings must have been sadly pent up and confined; it would be, above all, a miserable field for infant life; yet nothing can be more certain than that they were packed with people as full as they could hold. About the centre, on a pier larger that the rest, was reared a chapel, of Gothic architecture of the twelfth century, 60 feet by 20, and of two floors, dedicated to St. Thomas of Canterbury, and styled St. Peter's of the Bridge; a strange site, one would think, for an edifice of that sacred character, and yet we are assured that to rear religious houses upon bridges was by no means an uncommon practice in medieval times.  In the earlier days of London Bridge, the gate at the end towards the city was that on which the heads of executed traitors were exhibited; but in the reign of Elizabeth, this grisly show was transferred to the gate at the Southwark end, which consequently became recognised as the TRAITORS' GATE. A representation of this gate, with the row of heads above it, is here given, mainly as it appears in Vischer's View of London (seventeenth century). There was one clear space upon the bridge, of such extent that it was deemed a proper place for joustings or tournaments; and here, on St. George's Day 1390, was performed a tilting of extraordinary character. John de Wells, the English ambassador in Scotland, having boasted of the prowess of his countrymen at the Scottish court, a famous knight of that country, David Lindsay, Earl of Crawford, offered to put all questions on that point to trial by a combat on London Bridge. He was enabled by a royal safe-conduct to travel to London with a retinue of twenty-nine persons. The ground was duly prepared, and a great concourse of spectators took possession of the adjacent houses. To follow the narrative of Hector Baece: The signal being given, tearing their barbed horses with their spurs, they rushed hastily together, with a mighty force, and with square-ground spears, to the conflict. Neither party was moved by the vehement impulse and breaking of the spears; so that the common people affected to cry out that David was bound to the saddle of his horse, contrary to the law of arms, because he sat unmoved amidst the splintering of the lances on his helmet and visage. When Earl David heard this, he presently leaped off his charger, and then as quickly vaulted again upon his back without any assistance; and, taking a second hasty course, the spears were a second time shivered by the shock, through their burning desire to conquer. And now a third time were these valorous enemies stretched out and running together; but then the English knight was cast down breathless to the earth, with great sounds of mourning from his countrymen that he was killed. Earl David, when victory appeared, hastened to leap suddenly to the ground; for he had fought without anger, and but for glory, that he might shew himself to be the strongest of the champions, and casting himself upon Lord Wells, tenderly embraced him until he revived, and the surgeon came to attend him. Nor, after this, did he omit one day to visit him in the gentlest manner during his sickness, even like the most courteous companion. He remained in England three months, by the king's desire, and there was not one person of nobility who was not well affected towards him. EMANCIPATION OF BRITISH SLAVESThe 1st of August 1834 was the day on which the slaves in the British colonies were assigned, not to their actual freedom, but to a so-called 'apprenticeship' which was to precede and prepare for freedom. Lord (then Mr.) Brougham brought forward a measure to this great end in 1830; and Mr. Fowell Buxton another in 1832; but no act was passed till 1833. It provided that on the 1st of August in the following year, all slaves should become 'apprenticed labourers' to their masters, in two classes; that in 1838 and 1840, respectively, these two classes should receive their actual freedom; that twenty millions sterling should ultimately be paid to the masters, who would then lose the services of their slaves; and that this sum would be distributed rateably, according to the market-price of slaves in each colony, during the eight years 1823-1830. Many subsequent statutes modified the minor details, but left the main principle untouched. It was found, on a careful analysis, that on the 1st of August 1834 (all negroes born after that date, were born free), there were 770,280 slaves in the colonies affected by the Emancipation Act. A remarkable address was issued on this occasion by the Marquis of Sligo, governor of Jamaica: remarkable in relation to the paternal tone in which the negroes were addressed, as children to whom freedom was an unknown privilege, and who might possibly like a lazy life better than an industrious one, when enforced labour should cease: 'My Friends!-Our good king, who was himself in Jamaica long time ago, still thinks and talks a great deal of this island. He has sent me out here to take care of you, and to protect your rights; but he has also ordered me to see justice done to your owners, and to punish those who do wrong. Take my advice, for I am your friend, be sober, honest, and work well when you become apprentices; for should you behave ill, and refuse to work because you are no longer slaves, you will assuredly render yourselves liable to punishment. The people of England are your friends and fellow-subjects; they have shewn themselves such by passing a bill to make you all free. Your masters are also your friends; they have proved their kind feeling towards you all, by passing in the House of Assembly the same bill. The way to prove that you are deserving of all this goodness, is by labouring diligently during your apprenticeship. You will, on the 1st of August next, no longer be slaves; from that day you will be apprenticed to your former owners, for a few years, in order to fit you all for freedom. It will therefore depend entirely upon your own conduct, whether your apprenticeship shall be short or long; for should you run away, you will be brought back by the Maroons and the police, and have to remain in apprenticeship longer than those who behave well. You will only be required to work four days and a half in each week; the remaining day and a half in each week will be your own time, and you may employ it for your own benefit. Bear in mind, that every one is obliged to work: some work with their hands, some with their heads; but no one can live and be considered respectable with-out some employment. Your lot is to work with your hands. I pray you, therefore, do your part faithfully; for if you neglect your duty, you will be brought before the magistrates whom the king has sent out to watch you; and they must act fairly, and do justice to all, by punishing those who are badly disposed. Do not listen to the advice of bad people; for should any of you refuse to do what the law requires of you, you will bitterly repent it; for when at the end of the appointed time, all your fellow-labourers are released from apprenticeship, you will find yourselves condemned to hard labour in the workhouse for a lengthened period, as a punishment for your disobedience. If you follow my advice, and con-duct yourselves well, nothing can prevent your being your own masters, and to labour only for yourselves, your wives and children, at the end of four or six years, according to your respective classes. I have not time to go about to all the properties in this island, and tell you this myself. I have ordered this letter of advice to be printed, and to be read to you all, that you may not be deceived, and bring yourselves into trouble by bad advice or mistaken motives. I trust you will be obedient and diligent subjects to our good king, so that he may never have reason to be sorry for all the good he has done for you.' |