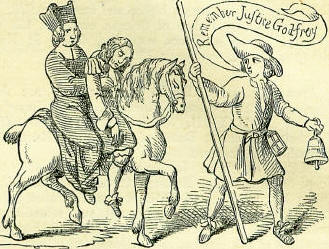

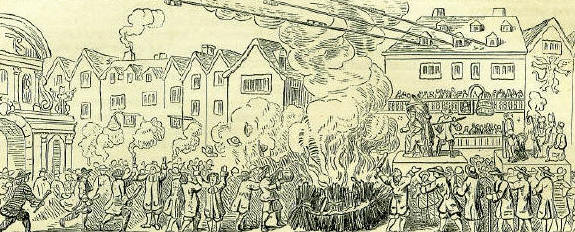

17th NovemberBorn: Vespasian, Roman emperor, 9 A. D.; Jean Antoine Nollet, natural philosopher, 1700, Pimpré, in Noyon; Louis XVIII of France, 1755, Versailles; Marshal Macdonald, Duke of Tarentum, Bonapartist general, 1765, Sancerre. Died: Valentinian I, Roman emperor, 375; Sir John de Mandeville, Eastern traveller, 1372, Liege; Queen Mary of England, 1558, St. James's Palace; John Pious, Prince of Mirandola, linguist and miscellaneous writer, 1494, Florence; Nicolas Perrot d'Ablancourt, translator of the classics, 1664, Ablancourt; John Earle, bishop of Salisbury, author of Microcosmographp, 1665, Oxford; Alain Rene le Sage, author of Gil Bias, 1747, Boulogne-sur-Mer; Thomas, Duke of Newcastle, statesman, 1768; Empress Catharine the Great of Russia, 1796, St. Petersburg; Charlotte, queen of George III, 1818, Kew; Thomas, Lord Erskine, eminent pleader, 1823, Almondell, near Edinburgh. Feast Day: St. Dionysius, archbishop of Alexandria, confessor, 265. St. Gregory Thaumaturgus, bishop and confessor, 270. St. Anian or Agnan, bishop of Orleans, confessor, 453. St. Gregory, bishop of Tours, confessor, 596. St. Hugh, bishop of Lincoln, confessor, 1200. SIR JOHN MANDEVILLEOn 17th November 1372, died at Liege the celebrated Sir John Mandeville or De Mandeville, who may be allowed to take rank as the father of English travellers, and the first in point of time, of that extended array of writers, who have made known to their countrymen, by personal inspection, the regions and peoples of the distant East. The ground traversed by him was nearly similar to that journeyed over in the previous century by the celebrated Venetian, Marco Polo, whose descriptions, however, of the countries which he visited must be admitted to be both much fuller and consonant to truth than those of his English successor. Whilst the Italian traveller restricts himself, in the main at least, to such statements as he was warranted in making, either as eye-witness of the circumstances described, or as communicated to him by trustworthy authorities, it is to be regretted that a great portion of Sir John Mandeville's work is made up of absurd and incredible stories regarding oriental productions and manners, which he has adopted without question, and incorporated into his book, from all sources of legendary information, classic, popular, and otherwise. Yet after carefully winnowing the chaff from the wheat, there remains much curious and interesting matter, which may be accepted as presenting a correct picture of Eastern Asia in the fourteenth century as it appeared to a European and Englishman of the day. Even the purely romantic and legendary statements in the narrative have their value as illustrating the general ideas prevalent in medieval times on the subject of oriental countries. Many of these travellers' wonders, so familiar to all who have read (and who has not in his childhood?) Sinbad the Sailor, will be found referred to in the work of Sir John Mandeville. Of the history of this enterprising traveller we know little beyond what he himself informs us in the introduction to his narrative. From this, and one or two other sources, we learn that he was born at St. Albans, in Hertfordshire, about 1300; devoted himself to mathematics, theology, and medicine (rather a heterogeneous assemblage of studies), and for some time followed the profession of a physician. This last occupation he abandoned after pursuing it for a very short time, and in 1322, he started on an eastern tour, the motives for which seem to have been principally the love of adventure, and desire of seeing strange countries, and above all others, the Holy Land, regarding which the recent fervour of the Crusades had excited an ardent interest in Western Europe. On Michaelmas-day, 1322, he quitted England on his travels, proceeding in the first instance to Egypt, into the service of whose sultan he entered, and fought for him in various campaigns against the Bedouin Arabs. He succeeded in ingratiating himself considerably with his employer, who, according to Mandeville's account, thus testified his sense of the English-man's merits. And he wolde have maryed me fulle highely to a gret princes doughter, gif that I wolde have forsaken my law and my beleve. But, I thank God, I had no wille to don it, for nothing that he behighten me. From Egypt Sir John proceeded to the Holy Land, and from thence continued his peregrinations till he reached the dominions of the great Khan of Tartary, a descendant of the celebrated Genghis, whose sovereignty extended over the greater part of Central and Eastern Asia, including the northern provinces of China or Cathay, as it was then termed by Europeans. Under his banners Mandeville took service, and fought in his wars with the king of Manci, whose territories seem to have corresponded to the southern division of the Celestial Empire. He appears subsequently to have travelled over the greater part of the continent of Asia, and also to have visited some of the East Indian Islands. The kingdom of Persia is described by him, and also the dominions of that celebrated medieval, and semi-mythical potentate, Prester John, whom from Mandeville's account we would infer to have been one of the princes of India, whilst other chroniclers seem to point to the sovereign of Abyssinia. After an absence of nearly thirty-four years, Sir John returned to his native country, and published an account of the regions visited by him in the East, which he dedicated to Edward III. It is to be regretted that in this there is so little personal narrative given, all reference to his own adventures being nearly comprised in the meagre and unsatisfactory statements which we have above furnished. Subsequently to its publication, Sir John seems to have gone again abroad on his travels, but the history of his latter days is very obscure. All that can be definitely ascertained is, that he died at Liege, in Belgium, and was buried in a convent in that town. A manuscript of Sir John Mandeville's travels, belonging to the fourteenth century, is preserved in the Cottonian collection in the British Museum. The first printed English edition was that issued from the Westminster press in 1499, by Winkyn de Worde. During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the work enjoyed a great reputation, second only to Marco Polo's, as an authority on all questions of oriental geography, and was translated into several languages. QUEEN ELIZABETH'S DAYViolent political and religious excitement characterised the close of the reign of King Charles II. The unconstitutional acts of that sovereign, and the avowed tendency of his brother toward the Church of Rome, made thoughtful men uneasy for the future peace of the country, and excited the populace to the utmost degree. It had been usual to observe the anniversary of the accession of Queen Elizabeth with rejoicings; and hence the 17th of November was popularly known as 'Queen Elizabeth's Day;' but after the great fire, these rejoicings were converted into a satirical saturnalia of the most turbulent kind. The Popish Plot, the Meal-tub Plot, and the murder of Sir Edmundbury Godfrey, had excited the populace to anti-papistical demonstrations, which were fostered by many men of the higher class, who were members of political and Protestant clubs. Roger North, who lived in these turbulent times, says that the Earl of Shaftesbury was the prime mover in all that opposed the court-party, and the head of the Green Ribbon Club, who held their meetings at the 'King's Head Tavern,' at the corner of Chancery Lane. They obtained their name from the green ribbon worn in their hats, to distinguish them in any street-engagement from clubbists of an opposite party. North says: this copious society were a sort of executive power in and about London; and by correspondence, all over England. They organised and paid for the great ceremonial pro-cessions and pope-burnings that characterised the years 1679-1681, and which were well calculated to keep up popular excitement, and inflame the minds of the most peaceable citizens. From the rare pamphlet, London's Defiance to Rome, which describes 'the magnificent procession and solemn burning of the pope at Temple Bar, November 17, 1679,' we learn that: the bells generally about the town began to ring about three o'clock in the morning;' but the great procession was deferred till night, when ' the whole was attended with one hundred and fifty flambeaus and lights, by order; but so many more came in volunteers, as made up some thousands At the approach of evening (all things being in readiness), the solemn procession began, setting forth from Moorgate, and so passing first to Aldgate, and thence through Leadenhall Street, by the Royal Exchange through Cheapside, and so to Temple Bar. Never were the balconies, windows, and houses more numerously lined, or the streets closer thronged, with multitudes of people, all expressing their abhorrence of popery with continued shouts and exclamations, so that 'tis modestly computed that, in the whole progress, there could not be fewer than two hundred thousand spectators.  The way was cleared by six pioneers in caps and red waistcoats, followed by a bellman bearing his lantern and staff, and ringing his bell, crying out all the way in a loud but dolesome voice: 'Remember Justice Godfrey!' He was followed by a man on horseback, dressed like a Jesuit, carrying a dead body before him, 'representing Justice Godfrey, in like manner as he was carried by the assassins to Primrose Hill.' We copy from a very rare print of the period, this, the most exciting part of the evening's display. Godfrey was a London magistrate, before whom the notorious Titus Oates had made his first deposition; he was found murdered in the fields at the back of Primrose Hill, with a sword run through his body, to make it appear that by falling upon it intentionally, he had committed suicide; but wounds in other parts of his person, and undeniable marks of strangulation, testified the truth. There was little need for a bell-man to recall this dark ,deed to the remembrance of the Londoners. The excitement was increased by another performer in the procession, habited as a priest, 'giving pardons very plentifully to all those that should murder Protestants, and proclaiming it meritorious.' He was followed by a train of other priests, and 'six Jesuits with bloody daggers;' then, by way of relief, came 'a consort of wind-musick.' This was succeeded by a long array of Catholic church dignitaries, ending with 'the pope, in a lofty glorious pageant, representing a chair of state, covered with scarlet, richly embroidered and fringed, and bedecked with golden balls and crosses.' At his feet were two boys with censers,' at his back his holiness's privy-councillor (the degraded seraphim, Anglicé, the devil), frequently caressing, hugging, and whispering him, and ofttimes instructing him aloud to destroy his majesty, to forge a Protestant plot, and to fire the city again, to which purpose he held an infernal torch in his hand.' When the procession reached the foot of Chancery Lane, in Fleet Street, it came to a stop; 'then having entertained the thronging spectators for some time with the ingenious fireworks, a vast bonfire being prepared just overagainst the Inner Temple gate, his holiness, after some compliments and reluctances, was decently toppled from all his grandeur into the flames.' This concluding feat was greeted by 'a prodigious shout, that might be heard far beyond Somerset House,' where the Queen Catharine was lodged at that time, but the ultra-Protestant author of this pamphlet, anxious to make the most of the public lungs, declares: twas believed the echo, by continued reverberations before it ceased, reached Scotland, France, and even Rome itself, damping them all with a dreadful astonishment. This show proved so immensely popular, that it was reproduced next year, with additional political pageantry. Justice Godfrey, of course, was there, but Mrs. Celliers and the Meal-tub figured also, accompanied by four Protestants, 'in bipartite garments of black and white,' to indicate their trimming vacillation; followed by a man bearing a banner, on which was inscribed, 'We Protestants in Masquerade usher in Popery.' Then came a large display of priests and clerical dignitaries, winding up with the pope, represented with his foot on the neck of the Emperor Frederick of Germany. After him came Dona Olimpia, and nuns of questionable character; the procession concluding with a scene of the trial, and execution by burning, of a heretic. This procession was also 'lively represented to the eye on a copper-plate,' and we copy as much of it as depicts the doings in Fleet Street, from Temple Bar to Chancery Lane. At the corner of the lane is the King's Head Tavern, the rendezvous of the Green Ribbon Club, agreeing exactly with North's description: This house was doubly balconied in the front for the clubsters to issue forth in fresco, with hats and no perukes; pipes in their mouths, merry faces, and diluted throats for vocal encouragement of the canaglia below, at the bonfires. From this house to the Temple Gate, lines cross the street for fireworks to pass. The scene is depicted at the moment when the effigy of the pope is pushed from his chair of state into the huge bonfire below, as if in judgment for the fate of the Protestant who is condemned to the stake in the pageant behind him. North speaks of 'the numerous platoons and volleys of squibs discharged' amid shouts that 'might have been a cure of deafness itself.' Dryden alludes to the popularity of the show in the epilogue to his OEdipus; when, after declaring he has done his best to entertain the public, he adds: We know not what you can desire or hope, To please you more, but burning of a pope! In the Letters to and from the Earl of Derby, he recounts his visit to this pope-burning, in company with a French gentleman who had a curiosity to see it. The earl says: I carried him within Temple Bar to a friend's house of mine, where he saw the show and the great concourse of people, which was very great at that time, to his great amazement. At my return, he seemed frighted that somebody that had been in the room had known him, for then he might have been in some danger, for had the mob had the least intimation of him, they had torn him to pieces. He wondered when I told him no manner of mischief was done, not so much as a head broke; but in three or four hours were all quiet as at other times. In 1682, the court professed great alarm lest some serious riots should result from these celebrations, and required the mayor to suppress them; but the civic magnates declined to interfere, and the show took place as usual. The following year it was announced that the pageantry should be grander than ever, but the mayor was now the nominee of the king,' and effectually suppressed the display, patrolling all the streets with officers till midnight, and having the City trained-bands in reserve in the Exchange, and a company of Horse Guards on the other side of Temple Bar. 'Thus ended these Diavolarias,' says Roger North.  Under somewhat similar excitement, an attempt was made in the reign of Queen Anne to reproduce these inflammatory processions and pageants. The strong feeling engendered by the claims of the High-church party under Dr. Sacheverell, and the fears entertained of the Pretender, led their opponents to this course. The pageants were constructed, and the procession arranged; but the secretary of state interfered, seized the stuffed figures, and prevented the display. It was intended to open the procession with twenty watchmen, and as many more link-boys; to be followed by bag-pipers playing Lilliburlero, drummers with the pope's arms in mourning, 'a figure representing Cardinal Gualteri, lately made by the Pretender Protector of the English nation, looking down on the ground in a sorrowful posture.' Then came burlesque representatives of the Romish officials; standard-bearers 'with the pictures of the seven bishops who were sent to the Tower; twelve monks representing the Fellows who were put into Magdalen College, Oxford, on the expulsion of the Protestants by James II' These were succeeded by a number of friars, Jesuits, and cardinals; lastly came 'the pope under a magnificent canopy, with a silver fringe, accompanied by the Chevalier St. George on the left, and his counsellor the Devil on the right. The whole procession clos'd by twenty men bearing streamers, on each of which was wrought these words: God bless Queen Anne, the nation's great defender! Keep out the French, the Pope, and the Pretender. After the proper ditties were sung, the Pretender was to have been committed to the flames, being first absolved by the Cardinal Gualteri. After that, the said cardinal was to have been absolved by the Pope, and burned. And then the devil was to jump into the flames with his holiness in his arms.' The very proper suppression of all this absurd profanity was construed into a ministerial plot against the Hanoverian succession. The accession of George I., a few years afterwards, quieted the fears of the nation, and ' Queen Elizabeth's Day' ceased to be made a riotous political anniversary. SIR HENRY LEE At a tournament held on the 17th November 1559, the first anniversary of the accession of Queen Elizabeth to the throne, Sir Henry Lee, of Quarendon, made a vow of chivalry, that he would, annually, on the return of that auspicious day, present himself in the tilt-yard, in honour of the queen; to maintain her beauty, worth, and dignity, against all-comers, unless prevented by age, infirmity, or other accident. Elizabeth having graciously accepted Sir Henry as her knight and champion, the nobility and gentry of the court, incited by so worthy an example, formed themselves into an honourable society of Knights Tilters, which, yearly assembling in arms, held a grand tourney on each successive 17th of November. In 1590, Sir Henry, feeling himself overtaken by age, resigned his assumed office of Queen's Knight, having previously received her majesty's permission to appoint the famous Earl of Cumberland as his successor. The resignation was conducted with all due ceremony. The queen being seated in the gallery, with Viscount Turenne, the French ambassador, the Knights Tilters rode slowly into the tilt-yard, to the sound of sweet music. Then, as if sprung out of the earth, appeared a pavilion of white silk, representing the sacred temple of Vesta. In this temple was an altar, covered with a cloth of gold, on which burned wax candles, in rich candlesticks. Certain princely presents were also on the altar, which were handed to the queen by three young ladies, in the character of vestals. Then the royal choir, under the leadership of Mr. Hales, sang the following verses, as Sir Henry Lee's farewell to the court: My golden locks, time hath to silver turned (Oh time too swift, and swiftness never ceasing), My youth 'gainst age, and age at youth have spurned; But spurned in vain, youth waneth by increasing. Beauty, strength, and youth, flowers fading bene, Duty, faith, and love, are roots and ever green. My helmet, now, shall make a hive for bees, And lover's songs shall turn to holy psalms: A man-at-arms must now sit on his knees, And feed on prayers, that are old age's alms. And so, from court to cottage, I depart, My saint is sure of mine unspotted heart. And when I sadly sit in homely cell, I'll teach my swains this carol for a song, Blest be the hearts, that think my sovereign well, Cursed be the souls, that think to do her wrong. Goddess, vouchsafe this aged man his right, To be your beadsman, now, that was your knight. After this had been sung, Sir Henry took off his armour, placing it at the foot of a crowned pillar, bearing the initials E. R. Then kneeling, he presented the Earl of Cumberland to the queen, beseeching that she would accept that nobleman for her knight. Her majesty consenting, Sir Henry armed the earl and mounted him on horseback; he then arrayed himself in a peaceful garb of black velvet, covering his head with a common buttoned cap of country fashion. At Ditchley, a former seat of the Lees, Earls of Litchfield, collateral descendants of Queen Elizabeth's knight, there was a curious painting of Sir Henry and his dog, with the motto, 'More Faithful than Favoured.' The traditional account of this picture, a copy of which is here engraved, is that Sir Henry, on retiring to rest one night, was followed to his bedroom by the dog. The animal, being deemed an intruder, was at once turned out of the room; but howled and scratched at the door so piteously that Sir Henry, for the sake of peace, gave it readmission, when it crept underneath the bed. After midnight, a treacherous servant, making his way into the room, was seized and pinned to the ground by the watchful dog. An alarm being given, and lights brought, the terrified wretch confessed that his object was to kill Sir Henry and rob the house. In commemoration of the event, Sir Henry had the portrait painted, as a momunent of the gratitude of the master, the ingratitude of the servant, and the fidelity of the dog. It is very possible that this anecdote and picture may have given rise to the well-known story of a gentleman rescued from murder, at a lonely inn, by the fidelity and intelligence of his dog, who, by preventing him from getting into bed, induced him to suspect some treacherous design on the part of his landlord, who at midnight, with his accomplices, ascended through a trap-door in the floor of the apartment, but were discomfited and slain by the gentleman, with the aid of the faithful animal. Sir Henry died at the age of eighty, in the year 1611. About fifty years ago, his epitaph could still be deciphered in the then ruined chapel of Quarendon, in Buckinghamshire. |