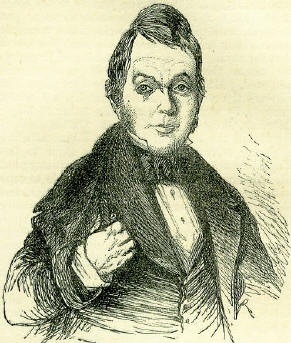

16th NovemberBorn: Tiberius, Roman Emperor, 42 B. C.; John Freinshemius, scholar and critic, 1608, Ulm; Jean le Rond d'Alembert, encyclopaedist, 1717, Paris; Francis Danby, artist, 1793, Wexford. Died: Aelfric, eminent Saxon prelate, 1005, Canterbury; Margaret, queen of Malcolm Canmore of Scotland, 1093; Henry III of England, 1272, Westminster; Perkin Warbeck, pretender to English crown, executed, 1499; Pierre Nicole, logician, of Port Royal, 1695, Chartres; James Ferguson, astronomer, 1776, London; Jean Lambert Tallien, Terrorist leader, 1820; George Wombwell, celebrated menagerie proprietor, 1850, Northallerton, Yorkshire; James Ward, animal painter, 1859, Cheshunt, Herts. Feast Day: St. Eucherius, bishop of Lyon, confessor, 450. St. Edmund, confessor, archbishop of Canterbury, 1242 ST. MARGARET, QUEEN OF SCOTLANDMany of the saints in the Romish calendar rest their claims to the title on grounds either wholly or partially fabulous, or which at best display a merit of a very dubious order. It is, however, satisfactory to recognise in the queen of Malcolm Canmore many of those traits which contribute to form a character of sterling virtue, to whose memory persons of all creeds and predilections must pay a respectful homage. It is true that much of our information regarding her is derived from the report of her confessor Turgot, whom clerical prejudices, as well as the inducements of personal friendship and courtly policy, may have led to delineate her with too flattering a pencil. Enough, however, remains after making all due deductions on this score, to confirm the idea popularly entertained in Scotland of the excellence of Queen Margaret. The niece of King Edward the Confessor, and the granddaughter of Edmund Ironside, the colleague of Canute, her youth was spent in exile, and under the proverbially salutary discipline of adversity. Her father and uncle narrowly escaped destruction at the hands of Canute, who, on the murder of their father, Edmund, sent the two young princes to the court of the king of Sweden, with instructions to put them to death privately. The chivalrous monarch refused to imbrue his hands in innocent blood, and sent the royal youths to Solomon, king of Hungary, by whom they were hospitably received and educated. Edmund the elder brother died, but Edward the younger married Agatha, a German princess, by whom he became the father of Edgar Atheling, Christina, and Margaret. On the death of Harold, at the Battle of Hastings, Edgar Atheling made an attempt to vindicate his right to the English crown against William the Conqueror; but his unenergetic character was quite unable to cope with the vigour and resources of the latter, and Edgar and his sister Margaret were consequently obliged to fly the kingdom. They were ship-wrecked on the coast of Scotland, and courteously received by King Malcolm Canmore, who was speedily captivated by the beauty and amiable character of Margaret. Her marriage to him took place in the year 1070, at the castle of Dunfermline, a place described by Fordun as surrounded with woods, rocks, and rivers, almost inaccessible to men or beasts by its situation, and strongly fortified by art. Margaret was at this time about twenty-four years of age. On her journey northwards to Dunfermline, she crossed the Firth of Forth at the well-known point where it narrows above Inverkeithing, and which since that event has been known by the designation of the Queensferrp. A stone is also still shewn on the road, a little below Dunfermline, called Queen Margaret's Stone, on which she is traditionally said to have rested. Of the palace or castle where she resided at Dunfermline, a small fragment still remains enclosed within the romantic grounds of Pittencrieff, and known as Malcolm Canmore's Tower. The union thus consummated was followed by a numerous offspring -six sons and two daughters. Three of the sons, Edgar, Alexander, and David ascended successively the throne of Scotland, and the elder daughter Maud, or Mathildes married Henry I, king of England. To the education of her children Margaret seems to have devoted herself with the most sedulous attention. She procured for them the best preceptors and teachers that the times afforded, and is said to have been particular in inculcating on them the necessity of restraining and correcting the frowardness of youth, by a proper exercise of discipline. Her own temper, however, appears to have been of the sweetest and most placid kind, and she was beloved among her servants and dependents for her innumerable acts of generosity and complaisance. To the poor also her charity was unbounded. Whenever she walked out, she was besieged by crowds of distressed persons, widows, orphans, and others, to whom she administered relief with a liberality which often exceeded the bounds of prudence. During the various incursions made by Malcolm into England, large numbers of the inhabitants of the country were taken prisoners, and to them the beneficence of Margaret was readily extended. She inquired into, and endeavoured as far as possible to mitigate their unhappy condition, and in many instances secretly paid their ransom out of her own funds, to enable them to return to their homes. She also erected hospitals in various places. With her husband, she seems to have lived on the most affectionate terms. Some of her acts, indeed, bear the marks of that spirit of asceticism and ostentatious humiliation so highly esteemed in that age. Every morning, she prepared a breakfast for nine little orphans, whom she fed on her bonded knees; and in the evening, she washed the feet of six poor persons, besides entertaining a crowd of mendicants each day at dinner. The season of Lent was observed by her with more than the wonted austerities of the Roman Catholic Church, allowing herself no food but a scanty meal of the simplest description, before retiring to rest, after a day spent in the closest exercises of devotion. One special act of hers in relation to religious ordinances deserves to be recorded. The observance of the Sabbath, which, previous to her marriage with Malcolm, had fallen greatly into desuetude, was revived and maintained. by her influence and example. It is not probable, however, that the staid and decorous observance of Sunday, so characteristic of Scotland, was derived from this incident, as a relapse appears to have taken place in succeeding reigns, and the strictly devotional character of the Sabbath to have been only again established at the Reformation. Notwithstanding the religious tendencies of Margaret, her court was distinguished by a splendour and elegance hitherto unknown in Scotland. Her own apparel was magnificent, and the feasts at the royal table were served up on gold and silver plate. Her acquaintance with the Scriptures and the writings of the fathers was extensive, and she is reported to have held numerous disputations with doctors of divinity on theological matters. An epitome of her moral excellence is presented in what is related of her, that 'in her presence nothing unseemly was ever clone or uttered.' The last days of this amiable queen were clouded by adversity and distress. The austerity of her religious practices prematurely undermined her health, and she was attacked by a tedious and painful illness, which she bore with exemplary resignation. She listened assiduously to the spiritual consolations of her faithful confessor Turgot, who thus relates her concluding words to him as quoted by Lord Hailes: Farewell; my life draws to a close, but you may survive me long. To you I commit the charge of my children, teach them above all things to love and fear God; and whenever you see any of them attain to the height of earthly grandeur, oh! then, in an especial manner, be to them as a father and a guide. Admonish and, if need be, reprove them, lest they be swelled with the pride of momentary glory, through avarice offend. God, or by reason of the prosperity of this world, become careless of eternal life. This in the presence of Him, who is now our only witness, I beseech you to promise and to perform. Her death at the last was accelerated by the news which she received of the death of her husband and eldest son before the castle of Alnwick, in Northumberland, an expedition in which she had vainly endeavoured to dissuade Malcolm from taking part in person. While lying on her couch one day, after having offered up some fervent supplications to the Almighty, she was surprised by the sudden entrance of her third son Edgar, from the army in England. Divining at once that some disaster had happened, she exclaimed: 'How fares it with the king and my Edward?' and then, on no answer being returned: 'I know all, I know all: by this holy cross, by your filial affection, I adjure you, tell me the truth.' Her son then replied: 'Your husband and your son are both slain.' The dying queen raised her eyes to heaven and murmured: 'Praise and blessing be to thee, Almighty God, that thou hast been pleased to make me endure so bitter anguish in the hour of my departure, thereby, as I trust, to purify me in some measure from the corruption of my sins; and thou, Lord Jesus Christ, who through the will of the Father, hast enlivened the world by thy death, oh! deliver me.' In pronouncing the last words, she expired on the 16th of November 1093, at the comparatively early age of forty-seven. She was canonized by Pope Innocent IV in 1251, but in the end of the seventeenth century, her festival was removed by the orders of Innocent XII, from the day of her death to the 10th of June. She was interred in the church of the Holy Trinity, at Dunfermline, which she had founded, and which, upwards of two hundred years afterwards,. received the corpse of the great King Robert. At the Reformation, the remains of Queen Margaret and her husband were conveyed privately by some adherents of the old religion to Spain, and deposited in a chapel which King Philip II built for their reception, in the palace of the Escurial. Here their tomb is said still to be seen, with the inscription: 'St. Malcolm, King, and St. Margaret, Queen.' The head of Queen Margaret, however, is stated to be now deposited in the church of the Scots Jesuits, at Douay. GEORGE WOMBWELL As a celebrity of his kind, George Wombwell deserves notice both for his own untiring industry and skill, and the prominence with which, for a long series of years, his name was familiar to the public, and more especially to the juvenile branches of the community. When a boy, he shewed great fondness for keeping birds, rabbits, dogs, and other animals, but the circumstance which led to his becoming the proprietor of a menagerie was for the most part accidental. A shoemaker by trade, and keeping a shop in Soho, he happened one day to pay a visit to the London Docks, where he saw some of the first boa constrictors which had been imported into England. These reptiles had then no great favour with showmen, as much from fear as ignorance of the art of managing them, and their marketable value was consequently less than it afterwards became. Wombwell purchased a pair for £75, and in the course of three weeks realized considerably more than that sum by their exhibition. He used afterwards to declare, that he entertained rather a partiality for the serpent tribe, as they had been the means of first opening his path to fame and fortune. Stimulated by the success thus achieved, he commenced his celebrated caravan peregrinations through the United Kingdom, visiting all the great fairs, such as those of Nottingham, Birmingham, Glasgow, and Donny-brook. In time, he amassed a handsome independence, but could never be prevailed on to retire to the enjoyment of ease and affluence, and he died, as he had lived, in harness. Neither did he ever abandon the closest attention to all matters connected with the menagerie, and might often be seen scrubbing and working away, as indefatigably as the humblest servant attached to the establishment. At the time of his death, Wombwell was possessed of three huge menageries, which travelled through different parts of the country, and comprised a magnificent collection of animals, many of them bred and reared by the proprietor himself. The cost of maintaining these establishments averaged at least £35 a day. The losses accruing from mortality and disease form a serious risk in the conduct of a menagerie, and Wombwell used to estimate that from this cause he had lost, from first to last, from £12,000 to £15,000. A fine ostrich, valued at £200, one day pushed his bill through the bars of his cage, and in attempting to withdraw it, broke his neck. Monkeys, likewise, frequently entailed great loss from their susceptibility to cold, which frequently, as in the case of human beings, cut them off by terminating in consumption. As regards the commercial value of wild beasts, we are informed that tigers have some-times been sold as high as £300, and at other times might be had for £100. A good panther is worth £100, whilst hyenas range from £30 to £40 each, and zebras from £150 to £200. We suspect that the profits of menagerie proprietors are at the present day considerably curtailed, when the establishment of zoological gardens, and the general declension of fairs and shows in the popular estimation, must have sensibly diminished the numbers of persons who used to flock to these exhibitions. |