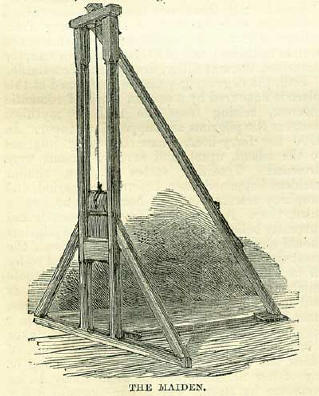

2nd JuneBorn: Nicolas Is Fevre, 1544, Paris. Died: Thomas, Duke of Norfolk, executed, 1572, Tower of London; James Douglas, Earl of Morton, beheaded at Edinburgh, 1581; Sir Edward Leigh, 1671, Rushall; Madeleine de Scuderi, romances, miscellaneous writings, 1701. Feast Day: Saints Pothinus, Bishop of Lyons, Sanctus, Attalus, Blandina, and the other martyrs of Lyons, 177; St. Erasmus, bishop and martyr, 303; Saints Marcellinus and Peter, martyrs, about 304. THE REGENT MORTON After ruling Scotland under favour of Elizabeth for nearly ten years, Morton fell a victim to court faction, which probably could not have availed against him if he had not forfeited public esteem by his greed and cruelty. It must have been a striking sight when that proud, stern, resolute face, which had frowned so many better men down, came to speak from a scaffold, protesting innocence of the crime for which he had been condemned, but owning sins enough to justify God for his fate. As is well known, the instrument employed on the occasion was one forming a sort of prototype of the afterwards more famous guillotine, and named The Maiden, of which a portraiture is here presented, drawn from the original, still preserved in Edinburgh. Morton is believed to have been the person who introduced The Maiden into Scotland, and he is thought to have taken the idea from a similar instrument which had long graced a mount near Halifax, in Yorkshire, as the appointed means of ready punishment for offences against forest law in that part of England. HALIFAX LAWThere is and hath been of ancient time a law, or rather a custom, at Halifax, that whosoever doth commit any felony, and is taken with the same, or confess the fact upon examination, if it be valued by four constables to amount to the sum of thirteen-pence halfpenny, he is forthwith beheaded upon one of the next market days (which fall usually upon the Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays), or else upon the same day that he is so convicted, if market be then holden. The engine wherewith the execution is done is a square block of wood, of the length of four feet and a half, which doth ride up and down in a slot, rabet, or regall, between two pieces of timber that are framed and set upright, of five yards in height. In the nether end of the sliding block is an axe, keyed or fastened with an iron into the wood, which, being drawn up to the top of the frame, is there fastened by a wooden pin (with a notch made into the same, after the manner of a Samson's post), unto the middest of which pin also there is a long rope fastened, that cometh down among the people; so that when the offender hath made his confession, and hath laid his neck over the nethermost block, every man there present doth either take hold of the rope (or putteth forth his arm so near to the same as he can get, in token that he is willing to see justice executed), and pulling out the pin in this manner, the head block wherein the axe is fastened doth fall down with such a violence, that if the neck of the transgressor were so big as that of a bull, it should be cut in sunder at a stroke, and roll from the body by an huge distance. If it be so that the offender be apprehended for an ox, sheep, kine, horse, or any such cattle, the self beast or other of the same kind shall have the end of the rope tied somewhere unto them, so that they being driven, do draw out the pin whereby the offender is executed. This sharp practice, in which originated the alliterative line in the Beggars' Litany: From Hell, Hull, and Halifax, good Lord deliver us! 'seems to date from time immemorial. To make an offender amenable to Halifax Law, it was necessary he should be taken within 'the forest of Hardwick and liberty of Halifax with the stolen property (of the value of thirteen-pence halfpenny or more) in his hands or on his back, or he could be convicted on his own confession. Upon apprehension the offender was taken before the Lord Bailiff, who immediately issued his summons to the constables of four towns within the district, to choose four 'Frith burghers' from each to act as jurymen. Before this tribunal accuser and accused were confronted, and the stolen article produced for valuation. No oaths were administered; and if the evidence against the prisoner failed to establish the charge, he was set at liberty there and then. If the verdict went against him, he left the court for the block, if it happened to be Saturday (the principal marketday), otherwise he was reserved for that day, being exposed in the stocks on the intervening Tuesdays and Thursdays. If the condemned could contrive to outrun the constable, and get outside the liberty of Halifax, he secured his own; he could not be followed and recaptured, but was liable to lose his head if ever he ventured within the jurisdiction again. One Lacy actually suffered after living peaceably outside the precincts for seven years; and a local proverbial phrase, 'I trow not, quoth Dinnis,' commemorates the escape of a criminal of that name, who being asked by people he met in his flight whether Dinnis was not to be beheaded that day, replied, 'I trow not!' He very wisely never returned to the dangerous neighbourhood. After the sentence had been duly carried out, a coroner's inquest was held at Halifax, when a verdict was given respecting the felony for which the unlucky thief had been executed, to be entered in the records of the Crown Office. On the 27th and 30th days of April 1650, Abraham Wilkinson, John Wilkinson, and Anthony Mitchell were charged before the sixteen representatives of Halifax, Skircoat, Sowerby, and Warley, with stealing sixteen yards of russet - coloured kersey and two colts; nine yards of cloth and the colts being produced in court. Mitchell and one of the Wilkinsons confessed, and the sentence passed with the following form: THE DETERMINATE SENTENCE -The prisoners, that is to say, Abraham Wilkinson and Anthony Mitchell, being apprehended within the liberty of Halifax, and brought before us, with nine yards of cloth as aforesaid, and the two colts above mentioned, which cloth is apprized to nine shillings, and the black colt to forty-eight shillings, and the grey colt to three pounds: All which aforesaid being feloniously taken from the above said persons, and found with the said prisoners; by the antient custom and liberty of Halifax, whereof the memory of man is not to the contrary, the said Abraham Wilkinson and Anthony Mitchell are to suffer death, by having their heads severed and cut from their bodies, at Halifax gibbet. The two felons were accordingly executed the same day, it being the great market-day, making the twelfth execution recorded from 1623 to 1650. This was destined to be the last; the bailiff was warned that if another such sentence was carried out, he would be called to account for it; and so the custom fell into desuetude, and Halifax Law ceased to be a special terror of thieves and vagabonds. SCUDERI AND HER ROMANCESFame occurs to authors in various ways. Some are famous in their lifetime and for ever; some are unknown in their lifetime, and become famous after death; some are famous in their lifetime, and are unread after death, but their names are remembered as once famous; and some are famous in their lifetime, but after death are so completely forgotten, that posterity loses even the record of their very names. Mademoiselle de Scuderi is not in the last unfortunate case. She was famous in her own day, she is now seldom read save by the literary antiquary; but it is not forgotten that she was famous. Her name is perpetually quoted, proverbially, as an instance of the evanescence of a great reputation. Madeleine de Scuderi was born at Havre-de-Grace, in 1607. Her family was noble, but of decayed fortune. Her mother dying while she was a child, she was adopted by an uncle, who, as he could not leave her money, spared neither pains nor expense in giving her a first-rate education. At his death, about her thirty-third year, she went to Paris to find a home with her brother George, a celebrated playwright, patronized by Richelieu, and thought a rival of Corneille. George could not afford to maintain her in idleness, and finding she had a lively wit and a ready pen, he set her to compose romances, which he published as his own. They sold well, and pleased far better than his dramas. George was an eccentric character, and it was said that he used to lock Madeleine up, in order that she might produce a proper quantity of writing daily. Soon the secret oozed out, and she speedily became one of the best known women, not only in Paris, but in Europe. Her publisher, Courbe, grew a rich man by the sale of her works, which were translated into every European language. When princes and ambassadors came to Paris, a visit to Mademoiselle do Scuderi was one of their earliest pleasures. She received a pension from Mazarin, which, at the request of Madame de Maintenon, Louis XIV augmented to 2,000 livres a year. Philosophers and divines united in her praise. Leibnitz sought the honour of her friendship and correspondence. Her Discourse on Glory received the prize of eloquence from the French Academy, in 1671. Her house was the centre of Parisian literary society, and she was the queen of the blue stockings, whom Moliere ridiculed in his Femmes Savantes, and his Precieuses Ridicules. No woman, in fact, who has ever written received more honours, more flatteries, and more substantial rewards. Endowed with great good-sense and amiability, she bore her prosperity through a very long life without offence, and without making a personal enemy. She was ugly; she knew it, owned it, and jested over it. It used to be said, that all who were happy enough to be her friends soon forgot her plain face, in the sweetness of her temper and the vivacity of her conversation. One gossip records her strong family pride, and the amusing gravity with which she was in the habit of saying, 'Since the ruin of our family,' as if it had been the overthrow of the Roman empire. She was never married, though she had many admirers; and, after a blameless and happy life, expired at the advanced age of ninety-four, on the 2nd of June 1701. Mademoiselle de Scuderi was a voluminous writer. Her romances alone occupy about fifty volumes, of from five to fifteen hundred pages each. Most of them are prodigiously long; Le Grand Cyrus and Clélie each occupy ten volumes, and took years to appear. They are, moreover, encumbered with episodes, the main story sometimes forming no more than a third of the whole. She laid her scenes nominally in ancient times and the East; but her characters are only French men and women masquerading under Oriental names. She delighted in company, and many wondered when she found leisure to write; but society was her study, and what she heard and saw she, with a romantic gloss, reproduced. She put her friends into her books, and all knew who was who, and detected one another's houses, furniture, and gardens in Nineveh, Rome, and Athens. Even under such cumbrous travestie we might resort to her pages for pictures of French society under le grand Monarque, but she made no attempt to depict the realities of life. In high-flying sentimental conversations about love and friendship all her personages pass their days; and their generosity, purity, and courage are only equalled by their uniform good-breeding and faculty for making fine speeches. Long ago has the world lost its taste for writing in that strain, and the de Scuderi romances would only move a modern novel reader to laughter, and then to yawning and sleep. BAPTISM OF KING ETHELBERTEthelbert was the Saxon king reigning in Kent, when Augustine landed there and introduced Christianity in a formal manner into England. After a while, this monarch joined the Christian church; his baptism, which Arthur Stanley considers as the most important since Constantine, excepting that of Clovis, took place on the 2nd of June 597. Unfortunately the place is not known; but we know that on the ensuing Christmas-day, as a natural consequence of the example set by the king, ten thousand of the people were baptized in the waters of the Swale, at the mouth of the Medway. |