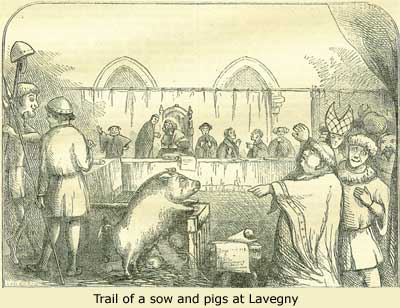

17th JanuaryBorn: B. de Montfaucon, antiquary, 1655; Archibald Bower, historical writer, 1686; George Lord Lyttelton, historian and poet, 1709; Victor Alfieri, poet, 1749; Johann Wolfgang Theophilus Mozart, musician, 1756. Died: John Ray, naturalist, 1705; Bishop Horne, 1792. Feast Day: St. Anthony, patriarch of monks, 356. SS Speusippus, Elcusippns, Meleusippns, martyrs. St. Nennins, abbot, 6th century. St. Sulpicius the Pious, archbishop, 591. St. Sulpicins the second, archbishop, 644. St. Milgithe, virgin, 7th century. ST. ANTHONYAntonius, reputed as amongst the earliest of anchorets, and commonly called the Patriarch of Monks, was a native of Egypt, born about the year 251. After leading an ascetic life for some time in his native village, he withdrew from human society and took up his abode in a cave. His abstinence, his self-inflicted punishments, the temptations of the evil one, the assaults of diomons, and the efficacy of his prayers, are all narrated by St. Athanasius. His manner of life was imitated by a great number of persons, who occasionally resorted to him for advice and instruction. Antonius seems indeed to have been the founder of the solitary mode of living, which soon extended from Egypt into other countries. During the persecution under Maximinus, about the year 310, some of the solitaries were seized in the wilderness, and suffered martyrdom at Alexandria, whither Antonius accompanied them, but was not subjected to punishment. After his return, he retired farther into the desert, but went on one occasion to Alexandria in order to preach against the Arians. The two monastic orders of St. Anthony originated long after the time of the saint,-one in Dauphine, in the eleventh century; and the other, a military order, in Hainault, in the fourteenth century. In Dauphine, the people were cured of the erysipelas, by the aid, as they thought, of St. Anthony; and the disease was afterwards called St. Anthony's Fire. It is scarcely necessary to remark that St. Anthony is one of the most notable of all the saints in the Romish calendar. One cannot travel anywhere in Europe at the present day, and particularly in Italy, without finding, in churches and monasteries, and the habits and familiar ideas of the people, abundant memorials of this early Egyptian anchorite. Even in Scotland, at Leith, a street reveals by its name where a monastery of St. Anthony once stood; while, on the hill of Arthur's Seat, overhanging Edinburgh, we still see a fragment of a small church that had been dedicated to him, and a fountain called St. Anton's Well. The Temptations of St. Anthony have, through St. Athanasius's memoir, become one of the most familiar of European ideas. Scores of artists from Salvator Rosa downwards, have exerted their talents in depicting these mystic occurrences. Satan, we are informed, first tried, by befuddling his thoughts, to divert him from the design of becoming a monk. Then he appeared to him in the form successively of a handsome woman and a black boy, but without in the least disturbing him. Angry at the defeat, Satan and a multitude of attendant fiends fell upon him during the night, and he was found in his cell in the morning lying to all appearance dead. On another occasion, they expressed their rage by making such a dreadful noise that the walls of his cell shook. 'They transformed themselves into shapes of all sorts of beasts, lions, bears, leopards, bulls, serpents, asps, scorpions, and wolves; every one of which moved and acted agreeably to the creatures which they represented: the lion roaring and seeming to make towards him; the bull to butt; the serpent to creep; and the wolf to run at him, and so, in short, all the rest; so that Anthony was tortured and mangled by them so grievously that his bodily pain was greater than before.' But, as it were laughingly, he taunted them, and the devils gnashed their teeth. This continued till the roof of his cell opened, a beam of light shot down, the devils became speechless, Anthony's pain ceased, and the roof closed again. Bishop Latimer relates a 'pretty story' of St. Anthony, 'who, being in the wilderness, had there a very hard and strait life, insomuch that none at that time did the like; to whom came a voice from heaven, saying, 'Anthony, thou art not so perfect as is a cobbler that dwelleth at Alexandria.' Anthony, hearing this, rose up forthwith and took his staff and went till he came to Alexandria, where he found the cobbler. The cobbler was astonished to see so reverend a father come to his house; when Anthony said unto him, 'Come and tell me thy whole conversation, and how thou spendest thy tune.' 'Sir,' said the cobbler, 'as for me, good works have I none, for my life is but simple and. slender; I am but a poor cobbler. In the morning when I rise, I pray for the whole city wherein I dwell, especially for all such neighbours and poor friends as I have: after I set me at my labour, where I spend the whole day in getting my living; and I keep me from all falsehood, for I hate nothing so much as I do deceitfulness; wherefore, when I make to any man a promise, I keep to it, and perform it truly. And thus I spend my time poorly with my wife and children, whom I teach and instruct, as far as my wit will serve me, to fear and dread God. And this is the sum of my simple life.' In this story, you see how God loveth those who follow their vocation and live uprightly without any falsehood in their dealing. Anthony was a great holy man; yet this cobbler was as much esteemed before God as he.' MONTFAUCON (on benefits of avoiding bad habits)A model of well-spent literary life was that of Bernard de Montfaucon. Overlooking many minor works, it is enough to regard his great ones: Antiquity explained by Figures, in fifteen folios, containing twelve hundred plates (descriptive of all that has been preserved to us of ancient art); and the Monuments of the French Monarchy, in five volumes. 'He died at the Abbey of St. Germain des Pre's, in 1741, at the age of eighty-seven, having preserved his faculties so entire, that nearly to the termination of his long career he employed eight hours a day in study. A very regular and abstemious life had so fortified his constitution that, during fifty years, he never was indisposed; nor does it appear that his severe literary labours had any tendency to abridge his days.' Several other literary Nestors could be cited to prove that the life of an author is not necessarily unhealthful or short. It is only when literary labour is carried to an extreme transcending natural power, or complicated with harassing cares and dissipation, that it proves destructive. When we see a man of letters sink at an early age, supposing there has been no original weakness of constitution, we may be sure that there has been some of these causes at work. When, as often happens, a laborious writer like the late Mr. Britton or Mr. John Nichols goes on, with the pen in his hand every day, till he has passed eighty, then we may be equally sure there has been prudence and temperance. But the case is general. Health and longevity are connected to a certain extent with habit. And there is some sense at bottom in what a quaint friend of ours often half jocularly declares; namely, that it would, as a rule, do invalids some good, if they were not so much sympathised with as they are, if they were allowed to know that they would be better (because more useful) members of society if they could contrive to avoid bad health; which most persons can to a certain extent do by a decent degree of self-denial, care, and clue activity. Deep-thinking philosophers have at all times been distinguished by their great age, especially when their philosophy was occupied in the study of Nature, and afforded them the divine pleasure of discovering new and important truths.... The most ancient instances are to be found among the Stoics and the Pythagoreans, according to whose ideas, subduing the passions and sensibility, with the observation of strict regimen, were the most essential duties of a philosopher. We have already considered the example of a Plato and an Isocrates. Apollonius of Tyanæa, an accomplished man, endowed with extraordinary powers both of body and mind, who, by the Christians, was considered as a magician, and by the Greeks and Romans as a messenger of the gods, in his regimen a follower of Pythagoras, and a friend to travelling, was above 100 years of age. Xenophilus, a Pythagorean also, lived 106 years. The philosopher Demonax, a man of the most severe manners and uncommon stoical apathy, lived likewise 100 years. 'Even in modern times philosophers seem to have obtained this pre-eminence, and the deepest thinkers appear in that respect to have enjoyed, in a higher degree, the fruits of their mental tranquillity. Newton, who found all his happiness and pleasure in the higher spheres, attained to the age of eighty-four. Euler, a man of incredible industry, whose works on the most abstruse subjects amount to above three hundred, approached near to the same age: and Kant, the first philosopher now alive, still shews that philosophy not only can preserve life, but that it is the most faithful companion of the greatest age, and an inexhaustible source of happiness to one's self and others.' THE DISCONTINUED 'SERVICES.'It is a curious proof of that tendency to continuity which marks all public institutions in England, that the services appointed for national thanksgiving on account of the Gunpowder Plot, for national humiliation regarding the execution of Charles I, and for thanksgiving with respect to the Restoration of Charles II, should have maintained their ground as holidays till after the middle of the nineteenth century. National good sense had long ceased to believe that the Deity had inspired James I with 'a divine spirit to interpret some dark phrases of a letter,' in order to save the kingdom from the 'utter ruin' threatened by Guy Fawkes and his associates. National good feeling had equally ceased to justify the keeping up of the remembrance of the act of a set of infuriated men, to the offence of a large class of our fellow-Christians. We had most of us become very doubtful that the blood of Charles I was 'innocent blood,' or that he was strictly a 'martyred sovereign,' though few would now-a-days be disposed to see him punished exactly as he was for his political short-comings and errors. Still more doubt had fallen on the blessing supposed to be involved in the miraculous providence 'by which Charles II was restored to his kingdom. Indeed, to say the very least, the feeling, more or less partial from the first, under which the services on these holidays had been appointed, had for generations been dead in the national heart, and their being still maintained was a pure solecism and a farce. It was under a sense of this being the case that, at the convocation of 1857, Dr Milman, Dean of St. Paul's, expressed a doubt whether we ought to command the English nation to employ in a systematic way opprobrious epithets towards Roman Catholics, and to apply divine epithets to the two Charleses. He was supported by Dr. Martin, Chancellor of the diocese of Exeter. Enough transpired to shew that Convocation did not attach much value to the retention of the services. In 1858, Earl Stanhope brought the matter formally before the House of Lords. He detailed the circumstances under which the services had originated; and then moved an address to the Crown, praying that the Queen would, by royal consent, abolish the services, as being derogatory to the present age. He pointed out that, although a nest of scoundrels planned a wicked thing early in the seventeenth century, it does not follow that the Queen should command her subjects to use offensive language towards Roman Catholics in the middle of the nineteenth. He also urged that we, in the present day, have a right to think as we please about the alleged divine perfections of the sovereigns of the Stuart family. From first to last there have been differences of opinion as to the propriety of these services; many clergymen positively refused to read them; and the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral omitted them without waiting for royal authority. It was striking to observe how general was the support which Earl Stanhope's views obtained in the House of Lords. The Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishops of London and Oxford, the Earl of Derby, besides those who generally ranked among liberal peers, supported the address, which was forthwith carried. A similar address was passed by the House of Commons. The Queen returned answers which plainly showed what the advisers of the Crown thought on the matter. Accordingly, on the 17th of January 1859, a royal warrant was issued, abolishing the special services for the three days named. It was immediately seen, however, that if the Acts of Parliament still remained in the Statute-book, clergy-men might occasionally be embarrassed in reference to them; and, accordingly, a new Act was passed in the same year, repealing the obnoxious statutes. Thus was a small but wholesome work done once for all. The pith of the whole subject is contained in a sensible observation made by the Archbishop of Canterbury: 'I hold it to be impossible, even if it were desirable, that we, at a distance of two or three centuries, should entertain the feelings or sympathise with the expressions which are found in these services; and it is very inexpedient that the people should be invited to offer up prayers and thanksgivings in which their hearts take no concern.' A remark may be offered in addition, at the hazard of appearing a little paradoxical-that it might be well if a great deal of history, instead of being remembered, could be forgotten. It would be a benefit to Ireland, far beyond the Encumbered Estates Act, if nearly the whole of her history could be obliterated. The oblivion of all that Sir Archibald Alison has chronicled would be a blessing to both France and England. Happy were it for England if her war for the subjugation of America could be buried in oblivion; and happy, thrice happy, would it be for America in future, if her warlike efforts of 1861 could be in like manner forgotten. Above all, it is surely most desirable that there should be no regular celebration by any nation, sect, or party, of any special, transaction, the memory of which is necessarily painful to some neighbouring state, or some other section of the same population. Let us just reflect for a moment on what would be thought of a man who, in private society, loved to taunt a neighbour with a lawsuit he had lost fifty years ago, or some criminality which had been committed by his great-granduncle! What better is it to remind the people of Ireland of their defeat at the Battle of the Boyne, or our Catholic fellow-Christians of the guilt of the infatuated Catesby and his companions? ST ANTHONY AND THE PIGS: LEGAL PROSECUTIONS OF THE LOWER ANIMALSSt. Anthony has been long recognized as the patron and protector of the lower animals, and particularly of pigs. Quaint old Fuller, in his Worthies, says: 'St. Anthony is universally known for the patron of hogs, having a pig for his page in all pictures, though for what reason is unknown, except, because being a hermit, and having a cell or hole digged in the earth, and having his general repast on roots, he and hogs did in some sort enter-common both in their diet and lodging.' Stow, in his Survey, mentions a curious custom prevalent in his time in the London markets: 'The officers in this city,' he says, 'did divers times take from the market people, pigs starved or otherwise unwholesome for man's sustenance; these they did slit in the ear. One of the proctors of St. Anthony's Hospital tied a bell about the neck, and let it feed upon the dunghills; no one would hurt or take it up; but if any one gave it bread or other feeding, such it would know, watch for, and daily follow, whining till it had somewhat given it; whereupon was raised a proverb, such a one will follow such a one, and whine as if it were an Anthony pig.' This custom was generally observed, and to it we are indebted for the still-used proverbial simile-Like a tantony pig. At Rome, on St. Anthony's day, the religious service termed the Benediction of Beasts is annually performed in the church dedicated to him, near Santa Maria Maggiore. It lasts for some days; for not only every Roman, from the pontiff' to the peasant, who has a horse, mule, or ass, sends his cattle to be blessed at St. Anthony's shrine; but all the English scud their job-horses and favourite dogs, and for the small offering of a couple of Paoli get them sprinkled, sanctified, and placed under the immediate protection of the saint. A similar custom is observed on the same day at Madrid and many other places. On the Continent, down to a comparatively late period, the lower animals were in all respects considered amenable to the laws. Domestic animals were tried in the common criminal courts, and their punishment on conviction was death; wild animals fell under the jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts, and their punishment was banishment and death by exorcism and excommunication. Nor was the latter a light punishment. We all know how St. Patrick exorcised the Irish reptiles into the sea; and St. Bernard, one day, by peevishly saying, 'Be thou excommunicated' to a blue-bottle fly, that annoyed him by buzzing about his ears, unwittingly destroyed the flies of a whole district. The prerogative of trying the domestic animals was founded on the Jewish law, as laid down in Exodus xxi 28, and other places in the Old Testament. In every instance advocates were assigned to defend the animals, and the whole proceedings, trial, sentence, and execution, were conducted with all the strictest formalities of justice. The researches of French antiquaries have brought to light the records of ninety-two processes against animals, tried in their courts from 1120 to 1740, when the last trial and execution, that of a cow, took place. The trials of wild animals of a noxious description, as rats, locusts, caterpillars, and such like, were, as has been already mentioned, conducted in the ecclesiastical courts. The proceedings were exceedingly complicated, and, not having the sanction of the Mosaical law, were founded on the following thesis: As God cursed the serpent, David the mountains of Gilboa, and our Saviour the barren fig tree; so, in like manner, the church. had full power and authority to exorcise, anathematise, and excommunicate all animate and inanimate things. But as the lower animals, being created before man, were the elder-born and first heirs of the earth, as God blessed them and gave them ' every green herb for meat,' as they were provided for in the ark, and entitled to the privileges of the sabbath, they must ever be treated with the greatest clemency, consistent with justice. Some learned canonists, however, disputed those propositions, alleging that authority to try and punish offences, under the law, implied a contract, quasi-contract, pact, or stipulation, between the supreme power that made and administered the law, and those subjected to it. They contended, that, the lower animals being devoid of intelligence, no such pact ever had been or could be made; and that punishments for injuries committed unintentionally and in ignorance of the law, were unjust. They questioned, also, the authority of the Church to anathematise those whom she did not undertake to baptize, and adduced the example of the Archangel Michael, who, when contending with Satan for the body of Moses, did not make a railing accusation against the 'Old Serpent,' but left it to the Lord to rebuke him. Such discussions appear like the amusing inventions of Rabelais, or Swift; but they were no jesting matter to the simple agriculturists who engaged in those litigations. The general course of a process was as follows: The inhabitants of the district being annoyed by certain animals, the court appointed experts to survey and report upon the damage committed. An advocate was then appointed to defend the animals, and shew cause why they should not be summoned. They were then cited three several times, and not appearing, judgment was given against them by default. The court next issued a monitoure, warning the animals to leave the district within a certain time, under penalty of adjuration; and if they did not disappear on or before the period appointed, the exorcism was with all solemnity pronounced. This looks straightforward enough, but the delays and uncertainties of the law-ecclesiastical law especially-have long been proverbial. The courts, by every available moans of delay, evaded the last extremity of pronouncing the exorcism, probably lest the animals should neglect to pay attention to it. Indeed, it is actually recorded that, in some instances, the noxious animals, instead of 'withering off the face of the earth,' after being anathematised, became more abundant and destructive than before. This the doctors, learned in the law, attributed neither to the injustice of the sentence, nor want of power of the court, but to the malevolent antagonism of Satan, who, as in the case of Job, is at certain times permitted to tempt and annoy mankind. A lawsuit between the inhabitants of the commune of St. Julien, and a coleopterous insect, now known to naturalists as the Eynchitus aureus, lasted for more than forty-two years. At length the inhabitants proposed to compromise the matter by giving up, in perpetuity, to the insects, a fertile part of the district for their sole use and benefit. Of course the advocate of the animals demurred to the proposition; but the court, overruling the demurrer, appointed assessors to survey the land, and, it proving to be well wooded and watered, and every way suitable for the insects, ordered the conveyance to be engrossed in due form and executed. The unfortunate people then thought they had got rid of a trouble imposed on them by their litigious fathers and grandfathers; but they were sadly mistaken. It was discovered that there had formerly been a mine or quarry of an ochreous earth, used as a pigment, in the land conveyed to the insects; and though the quarry had long since been worked out and exhausted, some one possessed an ancient right of way to it, which if exercised would be greatly to the annoyance of the new proprietors. Consequently the contract was vitiated, and the whole process commenced de novo. How or when it ended, the mutilation of the recording documents prevents us from knowing; but it is certain that the proceedings commenced in the year 1445, and that they had not concluded in 1487. So what with the insects, the lawyers, and the church, the poor inhabitants must have been pretty well fleeced. During the whole period of a process, religious processions and other expensive ceremonies that had to be well paid for, were strictly enjoined. Besides, no district could commence a process of this kind unless all its arrears of tithes were paid up; and this circumstance gave rise to the well-known French legal maxim-' The first step towards getting rid of locusts is the payment of tithes;' an adage that in all probability was susceptible of more meanings than one. The summonses were served by an officer of the court, reading them at the places where the animals frequented. These citations were written out with all technical formality, and, that there might be no mistake, contained a description of the animals. Thus, in a process against rats in the diocese of Autun, the defendants were described as dirty animals in the form of rats, of a greyish colour, living in holes. This trial is famous in the annals of French law, for it was at it that Chassanee, the celebrated jurisconsult-the Coke of France-won his first laurels. The rats not appearing on the first citation, Chassanee, their counsel, argued that the summons was of a too local and individual character; that, as all the rats in the diocese were interested, all the rats should be summoned, in all parts of the diocese. This plea being admitted, the curate of every parish in the diocese was instructed to summon every rat for a future day. The day arriving, but no rats, Chassanee said that, as all his clients were summoned, including young and old, sick and healthy, great preparations had to be made, and certain arrangements carried into effect, and therefore he begged for an extension of time. This also being granted, another day was appointed, and no rats appearing, Chassanee objected to the legality of the summons, under certain circumstances. A summons from that court, he argued, implied full protection to the parties summoned, both on their way to it and on their return home; but his clients, the rats, though most anxious to appear in obedience to the court, did not dare to stir out of their holes on account of the number of evil-disposed cats kept by the plaintiffs. Let the latter, he continued, enter into bonds, under heavy pecuniary penalties, that their cats shall not molest my clients, and the summons will be at once obeyed. The court acknowledged the validity of this plea; but, the plaintiffs declining to be bound over for the good behaviour of their cats, the period for the rats' attendance was adjourned sine die; and thus, Chassanee gaining his cause, laid the foundation of his future fame. Though judgment was given by default, on the non-appearance of the animals summoned, yet it was considered necessary that some of them should be present when the monitore was delivered. Thus, in a process against leeches, tried at Lausanne, in 1451, a number of leeches were brought into court to hear the monitoire read, which admonished them to leave the district in three days. The leeches, proving contumacious, did not leave, and consequently were exorcised. This exorcism differing slightly from the usual form, some canonists adversely criticised, while others defended. it. The doctors of Heidelberg, then a famous seat of learning, not only gave it their entire and unanimous approbation, but imposed silence upon all impertinents that presumed to speak against it. And, though they admitted its slight deviation from the recognised formula made and provided for such purposes, yet they triumphantly appealed to its efficiency as proved by the result; the leeches, immediately after its delivery, having died off, day by day, till they were utterly exterminated.  Among trials of individual animals for special acts of turpitude, one of the most amusing was that of a sow and her six young ones, at Lavegny, in 1457, on a charge of their having murdered and partly eaten a child. Our artist has endeavoured to represent this scene; but we fear that his sense of the ludicrous has incapacitated him for giving it with the due solemnity. The sow was found guilty and condemned to death; but the pigs were acquitted on account of their youth, the bad example of their mother, and the absence of direct proof as to their having been concerned in the eating of the child. These suits against animals not unfrequently led to more serious trials of human beings, on charges of sorcery. Simple country people, finding the regular process very tedious and expensive, purchased charms and exorcisms from empirical, unlicensed exorcists, at a much cheaper rate. But, if any of the parties to this contraband traffic were discovered, death by stake and fagot was their inevitable fate-infernal sorcerers were not to presume to compete with holy church. Still there was one animal, the serpent, which, as it had been cursed at a very early period in the world's history, might be exorcised and charmed (so that it could not leave the spot where it was first seen) by any one, lay or cleric, without the slightest imputation of sorcery. The formula was simply thus: 'By Him who created thee, I adjure thee, that thou remain in the spot where thou art, whether it be thy will to do so or otherwise; and I curse thee with the curse with which the Lord hath cursed thee.' But if a wretched shepherd was convicted of having uttered the following nonsense, termed 'the prayer of the wolf,' he was burned at the stake: Come, beast of wool, thou art the lamb of humility! I will protect thee. Go to the right about, grim, grey, and greedy beasts! Wolves, she-wolves, and young wolves, ye are not to touch the flesh, which is here. Get thee behind me, Satan!' French shepherds suffered fearfully in the olden time, through being frequently charged with sorcery; and, among the rustic population, they are still looked upon as persons who know and practise dark and forbidden arts. Legal proceedings against animals were not confined to France. At Basle, in 1474, a cock was tried for having laid an egg. For the prosecution it was proved that cocks' eggs were of inestimable value for mixing in certain magical preparations; that a sorcerer would rather possess a cock's egg than be master of the philosopher's stone; and that, in pagan lands, Satan employed witches to hatch. such eggs, from which proceeded animals most injurious to all of the Christian faith and race. The advocate for the defence admitted the facts of the case, but asked what evil animus had been proved against his client, what injury to man or beast had it effected? Besides, the laying of the egg was an involuntary act, and as such, not punishable by law. If the crime of sorcery were imputed, the cock was innocent; for there was no instance on record of Satan ever having made a compact with one of the brute creation. In reply, the public prosecutor alleged that, though the devil did not make compacts with brutes, he sometimes entered into them; and though the swine possessed by devils, as mentioned in Scripture, were involuntary agents, yet they, nevertheless, were punished by being caused to run down a steep place into the sea, and so perished in the waters. The pleadings in this case, even as recorded by Hammerlein, are voluminous; we only give the meagre outlines of the principal pleas; suffice it to say, the cock was condemned to death, not as a cock, but as a sorcerer or devil in the form of a cock, and was with its egg burned at the stake, with all the due form and solemnity of a judicial punishment. As the lower animals were anciently amenable to law in Switzerland, so, in peculiar circumstances, they could be received as witnesses. And we have been informed, by a distinguished Sardinian lawyer, that a similar law is still, or was to a very late period, recognised in Savoy. If a man's house was broken into between sunset and sunrise, and the owner of the house killed the intruder, the act was considered a justifiable homicide. But it was considered just possible that a man, who lived all alone by himself, might invite or entice a person, whom he wished to kill, to spend the evening with him, and after murdering his victim, assert that he did it in defence of his person and property, the slain man having been a burglar. So when a person was killed under such circumstances, the solitary house-holder was not held innocent, unless he produced a dog, a cat, or a cock that had been an inmate of the house, and witnessed the death of the person killed. The owner of the house was compelled to make his declaration of innocence on oath before one of those animals, and if it did not contradict him, he was considered guilt-less; the law taking for granted, that the Deity would cause a miraculous manifestation, by a dumb animal, rather than allow a murderer to escape from justice. In Spain and Italy the lower animals were held subject to the laws, as in France. Azpilceuta of Navarre, a renowned Spanish. canonist, asserts that rats when exorcised were ordered to depart for foreign countries, and that the obedient animals would, accordingly, march down in large bodies to the sea-coast, and thence set off by swimming in search of desert islands, where they could live and enjoy themselves, without annoyance to man. In Italy, also, processes against caterpillars and other 'small deer' were of frequent occurrence; and certain large fishes called terons, that used to break the fishermen's nets, were annually anathematised from the lakes and headlands of the north-western shores of the Mediterranean. Apropos of fishes, Maffei, the learned Jesuit, in his history of India, tells a curious story. A Portuguese ship, sailing to Brazil, fell becalmed in dangerous proximity to a large whale. The mariners, terrified by the uncouth gambols of the monster, improvised a summary process, and duly exorcised the dreaded cetacean, which, to their great relief, immediately sank to the lowest depths of ocean. THE SHREWSBURY TRIPLE FIGHTOn the 17th January 1667-8, there took place a piece of private war which, in its prompting causes, as well as the circumstances under which it was fought out, forms as vivid an illustration of the character of the age as could well be de-sired. The parties were George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, attended by Sir Robert Holmes and Captain William Jenkins, on one side; and Francis Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, attended by Sir John Talbot, a gentleman of the King's Privy Chamber, and Bernard Howard, a younger son of the Earl of Arundel, on the other. Pepys, in reference to this 'duell,' as he terms it, says, it was all 'about my Lady Shrewsbury, at that time, and for a great while before, a mistress to the Duke of Buckingham; and so her husband challenged him, and they met; and my Lord Shrewsbury was run through the body, from the right breast through the shoulder; and Sir John Talbot all along up one of his arms; and Jenkins killed upon the place, and the rest all in a little measure wounded.' (Pepys's Diary, iv. 15.) A pardon under the great seal, dated on February the 5th following, was granted to all the persons concerned in this tragical affair; the result of which proved more disastrous than had at first been anticipated, for Lord Shrewsbury died in consequence of his wound, in the course of the same year. It is reported that during the fight the Countess of Shrewsbury held her lover's horse, in the dress of a page. This lady was Anna Maria Brudenell, daughter of Robert Earl of Cardigan. She survived both her gallant and her first husband, and was married, secondly, to George Rodney Brydges, of Keynsham, in Somersetshire. |