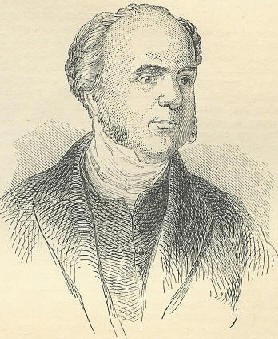

25th NovemberBorn: Lopez de la Vega, great Spanish dramatist, 1562, Madrid; Charles Kemble, actor, 1775, Brecon; Henry Mayhew, popular writer, 1812, London. Died: Pope Lucius III, 1185; Andrea Doria, Genoese admiral and patriot, 1560, Genoa; Edward Alleyn, actor, founder of Dulwieh College, 1626, Dulwich; John Tillotson, archhishop of Canterbury, eminent Whig divine, 1694, Lambeth.; Dr. Isaac Watts, poet and hymn writer, 1748, Stoke Newington; Henry Baker, author of The Microscope made Easy, 1774, London; Richard Glover, poet, 1785; Thomas Amory, eccentric author, 1788; Sir Augustus Wall Calcott, landscape painter, 1844, Kensington; John Gibson Lockhart, son in law and biographer of Sir Walter Scott, 1854, Abbotsford; Rev. John Kitt, illustrator of the Bible and sacred history, 1854, Cannstadt, was Stuttgart; Angus B. Reach, miscellaneous writer, 185G London. Feast Day: St. Catharine, virgin and martyr, 4th century. St. Erasmus or Elme, bishop and martyr, 4th century. ST. CATHARINEAmong the earlier saints of the Romish calendar, St. Catharine holds an exalted position, both from rank and intellectual abilities. She is said to have been of royal birth, and was one of the most distinguished ladies of Alexandria, in the beginning of the fourth century. From a child she was noted for her acquirements in learning and philosophy, and while still very young, she became a convert to the Christian faith. During the persecution instituted by the Emperor Maximinus I, St. Catharine, assuming the office of an advocate of Christianity, displayed such cogency of argument and powers of eloquence, as thoroughly silenced her pagan adversaries. Maximinus, troubled with this success, assembled together the most learned philosophers in Alexandria to confute the saint; but they were both vanquished in debate, and converted to a belief in the Christian doctrines. The enraged tyrant thereupon commanded them to be put to death by burning, but for St. Catharine he reserved a more cruel punishment. She was placed in a machine, composed of four wheels, connected together and armed with sharp spikes, so that as they revolved the victim might be torn to pieces. A miracle prevented the completion of this project. When the executioners were binding Catharine to the wheels, a flash of lightning descended from the skies, severed the cords with which she was tied, and shattered the engine to pieces, causing the death both of the executioners and numbers of the bystanders. Maximinus, however, still bent on her destruction, ordered her to be carried beyond the walls of the city, where she was first scourged and then beheaded. The legend proceeds to say, that after her death her body was carried by angels over the Red Sea to the summit of Mount Sinai. The celebrated convent of St. Catharine, situated in a valley on the slope of that mountain, and founded by the Emperor Justinian, in the sixth century, contains in its church a marble sarcophagus, in which the relics of St. Catharine are deposited. Of these the skeleton of the hand, covered with rings and jewels, is exhibited to pilgrims and visitors. A well known concomitant of St. Catharine, is the wheel on which she was attempted to be tortured, and which figures in all pictured representations of the saint. From this circumstance are derived the well kown circular window in ecclesiastical architecture, termed a Catharine wheel window, and also a firework of a similar form. This St. Catharine must not be confounded with the equally celebrated St. Catharine of Siena, who lived in the fourteenth century. THE FOUNDER OF DULWICH COLLEGEEdward Alleyn, the son of an innkeeper, was born at the sign of the 'Pye,' in Bishopsgate, London. In the days before theatres were specially erected for the purpose, the yards of old inns, surrounded by tiers of wooden galleries, were particularly eligible for the representation of plays. Young Alleyn must, therefore, have been early accustomed to witness stage performances. His father dying, and his mother marrying again one Browne, an actor and haberdasher, Alleyn was bred a stage player, and soon became the Roscius of his day. Ben Jonson thus hears testimony to his merit: If Rome so great, and in her wisest age, Feared not to boast the glories of her stage, As skilful Roscius and grave Æsop, men, Yet crowned with honours as with riches then; Who had no less a trumpet of their name Than Cicero, whose every breath was fame; How can such great example die in me, That Alleyn, I should pause to publish thee? Who both their graces in thy self hast more Outstript, than they did all that went before: And present worth in all dost so contract, As others speak, but only thou dost act. Wear this renown: tie just, that who did give So many poets life, by one should live. Exactly so, the poor player struts and frets his hour upon the stage, then dies, and is heard no more, but the poet lives for all time; and it was a brave thing for rare old Ben to acknowledge this, in the last two of the preceding lines: 'Tis just that who did give So many poets life, by one should live. Alleyn has been termed the Garrick of Shakspeare's era, and was no doubt intimate with the bard of Avon, as well as with Ben Jonson. A story is told of this grand trio spending their evening, as was their wont, at the Globe, in Blackfriars. On this occasion, Alleyn jocularly accused Shakspeare of having been indebted to him for Hamlet's speech, on the qualities of an actor's excellency. And Shakspeare, seemingly not relishing the innuendo, Jonson said: This affair needeth no contention, you stole it from Ned, no doubt; do not marvel: have you not seen him act, times out of number? Alleyn's first wife was Joan Woodward, the step daughter of one Henslowe, a theatrical speculator and pawnbroker; a thrifty man, withal, well calculated to foster and develop the acquisitive spirit, so characteristic of the future life of his step son in law. Soon after his marriage, Alleyn commenced to speculate in messuages and lands buying and selling and his exertions seem always to have been attended with profit. Amongst his other purchases, are inns of various signs as the Barge, the Bell and Cock, at the Bankside; the Boar's Head, probably the very house immortalised by his friend and fellow actor Shakspeare, in East cheap; the parsonage of Firle, in Sussex, and the manor of Kennington in Surrey, may be adduced as instances of the curious variety of Alleyn's property. Being appointed to the office of royal bearward, he became keeper and proprietor of the bear garden, which, besides bringing him an income of £500 per annum, led him to speculate in hulls, bears, lions, and animals of various kinds. One of the papers in Dulwich College, is a letter from one Fawnte, a trainer of fighting bulls, who writes as follows: Mr. Alleyn, my love remembered, I understood by a man, who came with two bears from the garden, that you have a desire to buy one of my bulls. I have three western bulls at this time, but I have had very ill luck with them, for one has lost his horn to the quick, that I think he will never he able to fight again; that is my old Star of the West, he was a very easy bull; and my bull Bevis, he has lost one of his eyes, but I think if you had him, he would do you more hurt than good, for I protest he would either throw up your dogs into the lofts, or else ding out their brains against the grates, so that I think he is not for your turn. Besides, I esteem him very high, for my Lord of Rutland's man bad me for him twenty marks. I have a bull, which came out of the west, which stands me in twenty nobles. If you should like him, you shall have him of me. Faith he is a marvellous good bull, and such a one as I think you have had but few such, for I assure you that I hold him as good a double bull as that you had of me last is a single, and one that I have played thirty or forty courses, before he bath been taken from the stake, with the best dogs. Though Alleyn had, without doubt, a keen eye for a bargain, a ready hand to turn a penny, and an active foot for the main chance, he was, unlike many men of that description, of a true, affectionate, and kindly nature; ever anxious for the welfare and happiness of his home and its inmates. In his letters, when from home, he playfully styles his wife 'mecho, mousin, and mouse'; speaks of her father as 'Daddy Henslowe'; and her sister, as 'Sister Bess', or 'Bess Dodipoll', the latter appellation probably derived from some theatrical character. When the plague was raging, in his absence from London, he thoughtfully and playfully writes to his wife: My good, sweet mouse, keep your house fair and clean, which I know you will, and every evening throw water before your door; and have in your windows good store of rue and herb of grace, and with all the grace of God, which must be obtained by prayers; and, so doing, o doubt but the Lord will mercifully defend you. His interest in home matters, among all his more money making transactions, never seems to flag. On another occasion he writes: Mouse, you send me no news of any things; you should send me of your domestical matters, such things as happen at home, as how your distilled water proves, or this or that. It is little wonder to us, that such a man, when finding himself advanced in years, without an heir, should devote his property to the benefit of the poor. But the had repute, that anciently attached to an actor's profession, made the circumstance appear in his own day a miracle, which, of course, was explained by its consequent myth. According to the latter, Alleyn, when acting the part of a demon on the stage, was so terrified by the apparition of a real devil, that he forthwith made a vow to bestow his substance on the poor, and subsequently fulfilled this engagement by building Dulwich College. The bad odour in which an actor was formerly held, is clearly exhibited by Fuller, who, speaking of Alleyn, quaintly says: In his old age, he mule friends of his unrighteous mammon, building therewith a fair college at Dulwich, for the relief of poor people. Some, I confess, count it built on a foundered foundation, seeing, in a spiritual sense, none is good and lawful money, save what is honestly and industriously gotten; hut, perchance, such who condemn Master Alleyn herein, have as bad shillings in the bottom of their own bags, if search were made therein. Thus he, who outacted others, outdid himself before his death. In further evidence of the disrepute attaching to actors in these days, it may be mentioned here, probably for the first time in print, that Izaak Walton, in his Life of Dr. Donne, has unworthily suppressed the fact, that Donne's daughter, Constance, was Alleyn's second wife. There were other reasons, however, for maintaining a prudent silence on this point; by a letter preserved at Dulwich, it would appear that Donne attempted to cheat Alleyn out of his wife's dowry. Exercising his practical genius, Alleyn had his college built during his lifetime. In 1619, it was opened with a sermon and an anthem; then the founder read the Act of creation; and the party, consisting of the Lord Chancellor, the Earl of Arundel, Inigo Jones, and others of similar position and consequence, went to dinner. Each item of the feast, and its price, is carefully recorded in Alleyn's diary. Suffice it to say here, that they had beef, mutton, venison, pigeons, godwits, oysters, anchovies, grapes, oranges, &c., the whole washed down by eight gallons of claret, three quarts of sherry, three quarts of white wine, and two hogsheads of beer. Alleyn then took upon himself the management of his college of God's Gift; living in it among the twelve poor men and twelve poor children, whom his bounty maintained, clothed, and educated. Here he was visited by the wealthy and noble of the land; and here he lost his faithful partner, Joan Woodward, and soon after married Constance, daughter of Dr. Donne. Alleyn administered the affairs of his college till his death, which took place in the sixty first year of his age, on the 25th of November 1626. With a pardonable wish to preserve his name in connection with the charity he founded, Alleyn appointed that the master and governor thereof should always be of the blood and surname of Alleyn. So strictly was this rule kept, that one Anthony Allen, a candidate for the mastership, was rejected in 1670, for want of a letter y in his name; but that objection has since been overruled. Alleyn did not forget the people among whom he was born, nor those among whom he made his money. By his last will and testament Edward Alleyn, Esquire, Lord of the Manor of Dulwich, founded ten alms houses, for ten poor people of the parish of St. Botolph's, Bishopsgate; and ten alms houses for ten poor people of the parish of St. Saviour's, Southwark, where his bear garden had so splendidly flourished. And, forgetting the ill treatment he received from his father in law, he amply provided for his widow with a legacy of £1600; no mean fortune according to the value of money in those days. DR. KITTO Per ardua was the motto graven on John Kitto's seal, and a more apt one he could scarcely have chosen. He was born in Plymouth in 1804, and as an infant was so puny, that he was hardly expected to live. He was carried in arms long after the age when other children have the free use of their limbs, and one of his earliest recollections was a headache, which afflicted him with various intermissions to the end of his days. His father was a master builder, but was daily sinking in the world through intemperate habits. Happily the poor child had a grandmother, who took a fancy for him, and had him to live with her. She was a simple and kindly old woman, and entertained her little Johnny' for hours with stories about ghosts, wizards, witches, and hobgoblins, of which she seemed to have an exhaustless store. She taught him to sew, to make kettle holders, and do patch work, and in fine weather she led him delightful strolls through meadows and country lanes. As he grew older, a taste for reading shewed itself, which grew into a consuming passion, and the business of his existence became, how to borrow hooks, and how to find pence to buy them. He had little schooling, and that between his eighth and eleventh years, frequently interrupted by seasons of illness. When he was ten, his affectionate grandmother became paralysed, and he had to return to his parents, who found him a situation in a barber's shop. One morning a woman called, and told Kitto she wished to see his master. The guileless boy went to call him from the public house, and in his absence she made off with the razors. In his rage at the loss, the barber accused Kitto of being a confederate in the theft, and instantly discharged him. His next employment was as assistant to his father, and in this service occurred the great misfortune of his life. They were repairing a house in Batter Street, Plymouth, in 1817, and John had just reached the highest round of a ladder, with a load of slates, and was in the act of stepping on the roof, when his foot slipped, and he fell from a height of five and thirty feet on a stone pavement. He bled profusely at the mouth and nostrils, but not at the ears, and neither legs nor arms were broken. For a fortnight he lay unconscious. When he recovered, he wondered at the silence around him, and asking for a book, was answered by signs, and then by writing on a slate. 'Why do you write to me?' exclaimed the poor sufferer. 'Why do you not speak? Speak! speak!' There was an interchange of looks and seeming whispers; the fatal truth could not be concealed; again the scribe took his pencil, and wrote: You are deaf!' Deaf he was, and deaf he remained until the end of his life. If the prospect of poor Kitto's life was dark before, it was now tenfold darker. His parents were unable to assist him, and left him in idleness to pursue his reading. He waded and groped in the mud of Plymouth harbour for bits of old rope and iron, which he sold for a few pence wherewith to buy books. He drew and coloured pictures, and sold them to children for their half pence. He wrote labels, to replace those in windows, announcing 'Logins for singel men,' and hawked them about town with slight success. By none of these means could he keep himself in food and raiment, and in 1819, much against his will, he was lodged in the workhouse, and set to learn shoe making. There his gentle nature and studious habits attracted the attention and sympathy of the master, and procured him a number of indulgences. He commenced to practise literary composition, and quickly attained remarkable facility and elegance of style. He began to keep a diary, and was prompted by the master to write lectures, which were read to the other workhouse boys. At the end of 1821, he was apprenticed to a shoemaker, who abused and struck him, and made him so miserable, that the idea of suicide not infrequently arose to tempt him. Here, however, Kitto's pen came to his effectual help, and his well written complaints were the means of the dissolution of his apprenticeship and readmission to the workhouse after six months of intolerable wretchedness. Mean while the literary ability of the deaf pauper boy began to be known; he was allowed to read in the Public Library; and some of his essays were printed in the Plymouth Journal. In the end there was written in the admission book of the work house John Kitto discharged, 1823, July 17th. Taken out under the patronage of the literati of the town. Kitto's first book appeared in 1825, consisting of Essays and Letters, with a short Memoir of the Author. It brought him little profit, but served to widen his circle of friends. One of these, Mr. Grove, an Exeter dentist, invited him to his house, and liberally undertook to teach him his own art; but after a while, hoping to turn his talents to better account, he had him introduced to the Missionary College at Islington, to learn printing. From thence he was sent to Malta, to work at a press there; but Kitto was much more inclined to private study than to mechanical occupation, and his habits not giving satisfaction to the missionaries, he returned to England in 1829, and set out with Mr. Grove on a religious mission to the east. For four years he travelled in Russia, the Caucasus, Armenia, and Persia. Whilst living at Bagdad in 1831, the plague broke out, in which about fifty thousand perished, or nearly three fourths of the inhabitants of the city. In this dreadful visitation, Mr. Grove lost his wife. Kitto was restored to his native land in safety in 1833, with a mind enriched and enlarged with a rare harvest of experience. Anxious, because with o certain means of livelihood, he fortunately procured an introduction to the secretary of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, and was employed by Mr. Charles Knight as a contributor to the Penny Magazine. Proving a capable and steady workman, he obtained the promise of constant occupation, on the strength of which he married, and in his wife found a helpmate literary and domestic. Mr. Knight, in 1835, projected a Pictorial Bible, with notes, and intrusted the editorship to Kitto. It was published in numbers, it was praised everywhere, it sold well, and its execution clearly indicated the line in which Kitto was destined to excel. He was next engaged on a Pictorial History of Palestine, then on a Cyclopedia of Biblical Literature, and finally on eight volumes of Daily Bible Illustrations. Besides these, he produced a number of minor works in illustration of the Scriptures, and started and edited a quarterly Journal of Sacred Literature. These writings made the name of Kitto a familiar word in every religious household in the land, and in 1850 he was placed for a pension of £100 a year on her Majesty's civil list, in consideration of his services. Kitto was a ready writer, but at the same time painstaking and correct; and the production of such a mass of literature as lies under his signature, within a period of less than twenty years, entailed the necessity of perpetual labour. The working day of the British Museum, he wrote to Mr. Knight, is six hours mine is sixteen hours. His deafness, as well as habits of incessant industry, cut him off from society, and he seldom saw any visitors except such as had actual business to transact. He confessed to a friend, in the summer of 1851, that he had not crossed his threshold for six weeks. His work was his joy, he loved nothing better; but the strain he put upon his fragile constitution was too great. Congestion of the brain set in; he was told his only chance for life lay in perfect rest and abstinence from work for a year or two; but he insisted on completing his literary engagements, and alleged, truly, that he had a wife and ten children to provide for. A number of his admirers subscribed ample funds to justify some years of repose, and in the August of 1851 he retired to Cannstadt, in Würtemherg, but it was too late. On the 25th of November he died at Cannstadt, and was there buried. In his seventeenth year, Kitto wrote this description of himself, which, making allowance for age, might serve for his picture at fifty, with the addition perhaps of an inch or two to his stature. I am four feet eight inches high; my hair is stiff and coarse, of a dark brown colour, almost black my head is very large, and, I believe, has a tolerable good lining of brain within. My eyes are brown and large, and are the least unexceptionable part of my person; my forehead is high, eyebrows bushy; my nose is large; my mouth very big teeth well enough; my limbs are not ill shaped my legs are well shaped. DOUBLE CONSCIOUSNESS: ALTERNATE SANITY AND INSANITYAn inquest, held in London on the 25th of November 1835, afforded illustrative testimony to that remarkable duality, double action, or alternate action of the mind, which physiologists and medical men have so frequently noticed, and which has formed the basis for so many theories. Mr. Mackerel, a gentleman connected with the East India Company, and resident in London, committed suicide by taking prussic acid, while labouring under an extraordinary paroxysm of delusions. During a period of four years, he had had these delusions every alternate day. Dr. James Johnson, his physician, had bound himself by a solemn promise to the unhappy man, never to divulge to any human being the exact nature of the delusions in question. Fulfilling this promise, he avoided giving to the jury any detailed account. The doctor stated that the delusions under which his patient laboured, while accompanied by most dreadful horrors and depression of mind, had not the remotest reference to any act of moral guilt, or to any circumstance in which the community could have an interest, but turned on an idle circumstance equally unimportant to himself and to others, but still were capable of producing a most extraordinary horror of mind. Mr. Mackerell called his two sets of days his good days and bad days. On his bad days he would, if possible, see no one, not even his physician. On his good days he talked earnestly with Dr. Johnson concerning his malady; and said that although what he suffered on his had days in body and mind might induce many men to rush madly upon suicide for relief, yet he himself had too high a moral and religious sense ever to be guilty of such an act. The delusion, Dr. Johnson declared, was not of a kind that would have justified any restraint, or any imputation of what is usually called insanity. It was on one subject only, a true monomania, that a hallucination prevailed. Whether in London or the country, traveling by road or by sea, this monomania regularly returned every alternate day, beginning when he woke in the morning, and lasting all the day through. The miserable victim felt the first attack of it at a period of unusual excitement and disappointment; and from that time it gradually strengthened until his death leaving him on the intermediate days, however, a clear headed and perfectly sane man: nay, a highly educated gentleman, of very superior intellectual powers. On two different occasions, his alternations of good and bad days influenced his proceedings in a curious way, leading him to undo each day what had been done the day before. It was just before the era of railways, when long journeys occupied two or more days and nights in succession. At one time, he secured a passage in the mail to Paisley; but on reaching Manchester he quitted the coach, and returned by the first conveyance to London. Again he quitted London by mail for Paisley, but turned back at Birmingham. A third time he engaged a place in the mail to Paisley, but did not start at all, and sent his landlord to make the best bargain he could with the clerk at the coach office for a return of a portion of the fare. It would appear that his good days gave him an inducement to travel northward, but the bad days then supervened, and changed his plans. He committed suicide, in spite of his oft expressed religious views, on one of his good days (for the persons in whose house he lived kept a regular account of these singular alternations), having been apparently worn out with the unutterable miseries of one half of his waking existence. Dr. Wigan, in his curious view of insanity, dues not mention this particular case; but he adduces two others of alternate sanity and insanity, or at least double manifestations of mental power. We have examples of persons who, from some hitherto unexplained cause, fall suddenly into, and remain for a time, in a state of existence resembling somnambulism; from which, after many hours, they gradually awake having no recollection of anything that has occurred in the preceding state; although, during its continuance, they had read, written, and conversed, and done many other acts implying an exercise, however limited, of the understanding. They sing or play on an instrument, and yet, on the cessation of the paroxysm, are quite unconscious of everything that has taken place. They now pursue their ordinary business and avocations in the usual manner, perhaps for weeks; when suddenly the somnambulic state recurs, during which all that had happened in the previous attack comes vividly before them, and they remember it as perfectly as if that disordered state were the regular habitual mode of existence of the individual the healthy state and its events being now as entirely forgotten as were the disordered ones during the healthy state. Thus it passes on for many months, or even years. Again, in one peculiar form of mental disease, an adult becomes a perfect child, is obliged to undertake the labour of learning again to read and write, and passes gradually through all the usual elementary branches of education makes considerable progress, and finds the task becoming daily more and more easy; but is entirely unconscious of all that had taken place in the state of health. Suddenly she is seized with a kind of fit, or with a sleep of preternatural length and intensity, and wakes in full possession of all the acquired knowledge which she had previously possessed, but has no remembrance of what I will call her child state, and does not even recognize the persons or things with which she then became acquainted. She is exactly as she was before the first attack, and as if the disordered state had never formed a portion of her existence. After the lapse of some weeks, she is again seized as before with intense somnolency, and after a long and deep sleep wakes up in the child state. She has now a perfect recollection of all that previously occurred in that state, resumes her tasks at the point where she had left off, and continues to make progress as is person would do who was of that age and under those circumstances; but has once more entirely lost all remembrance of the persons and things connected with her healthy [or adult] state. This alternation recurs many times, and at last becomes the established habit of the individual like an incurable ague. There are numerous recorded cases in which a person knows that he or she is subject to alternate mental states, and can reason concerning the one state while under the influence of the other. Humboldt's servant, a German girl, who had charge of is child, entreated to be sent away; for whenever she undressed it, and noticed the whiteness of its skin, she felt an almost irresistible desire to tear it in pieces. A young lady in a Paris asylum had, at regular intervals, a propensity to murder some one; and when the paroxysm was coming on, she would request to be put in a strait waistcoat, as a measure of precaution. A country woman was seized with a desire to murder her child whenever she put it into her cradle, and she used to pray earnestly when she felt this desire coming on. A butcher's wife often requested her husband to keep his knives out of her sight when her children were nigh; she was afraid of herself. A gentleman of good family, and estimable disposition, had a craving desire, when at church, to run up into the organ loft and play some popular tune, especially one with jocular words attached to it. All these cases, and many others of a kind more or less analogous, Dr. Wigan attributes to a duality of the mind, connected with a duality of the brain,. He maintains that the right and left halves of the brain are virtually two distinct brains, dividing between them the organism of the mental power. Both may be sound, both may be unsound in equal degree, both may be unsound in unequal degree, or one may be sound and the other unsound. The mental phenomena may exhibit, consequently, varying degrees of sanity and insanity. This view has not met with much acceptance among physiologists and psychologists; but, nevertheless, it is worthy of attention. |