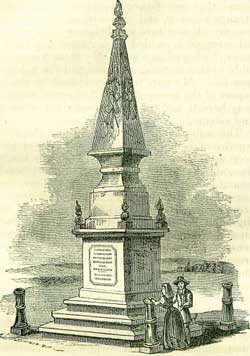

16th JanuaryBorn: Richard Savage, poet, 1697. Died: Edmund Spenser, poet, 1599; Edward Gibbon, historian, 1794; Sir John Moore, 1809; Edmund Lodge, herald, 1839. Feast Day: St. Marcellus, pope, martyr, 310. St. Macarius, the elder, of Egypt, 390. St. Honoratus, archbishop of Arles, 429. St. Fursey, son of Fintan, king of part of Ireland, 650. Five Friars, minors, martyrs. St. Henry, hermit, 1127. EDWARD GIBBON The confessions or statements of an author regarding the composition of a great work are generally interesting. Gibbon gives an account both of the formation of the design of writing his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, and of the circumstances under which that magnificent book was finished. At about twenty-seven years of age he inspected the ruins of Rome under the care of a Scotchman 'of experience and taste,' named Byers; and 'it was at Rome,' says he, 'on the 15th of October 1764, as I sat musing amidst the ruins of the Capitol, while the bare-footed friars were singing vespers in the Temple of Jupiter, that the idea of writing the decline and fall of the city first started to my mind.' It is to be observed that he thought only of the history of the city, not of the empire, to which his ideas finally expanded. Gibbon commenced the writing of his history after settling in a house in London about 1772. The latter moiety of the work was composed in an elegant mansion at Lausanne, in Switzerland, to which he retreated on being disappointed in a political career in England. The whole work occupied. about fifteen years. 'It was,' says he-and the passage can never be read without the deepest interest-' it was on the day, or rather night, of the 27th of June 1787, between the hours of eleven and twelve, that I wrote the last lines of the last page, in a summer-house in my garden. After laying down my pen, I took several turns in a berceau, or covered walk of acacias, which commands a prospect of the country, the lake, and the mountains. The air was temperate, the sky was serene, the silver orb of the moon was reflected from the waters, and all nature was silent. I will not dissemble the first emotions of joy on recovering my freedom, and, perhaps, the establishment of my fame. But my pride was soon humbled, and a sober melancholy was spread over my mind, by the idea that I had taken an everlasting leave of an old and agreeable companion, and that whatsoever might be the future fate of my History, the life of the historian must be short and precarious.' The historian was then fifty. Gibbon, as is well known, spent his life in celibacy, and was thus the better fitted for undertaking and carrying through a great literary work. Partly in consequence of the sedentary life to which his task confined him, he became extremely obese. There is a story representing him as falling in love, while at Lausanne, with a young lady of great beauty and merit, and which goes on to describe him as one day throwing himself at her feet to declare his passion, when it was found impossible for him to rise again till he was extricated by the laughing damsel from his ludicrous position. George Coleman the Younger has painted the scene in verse of by no means great merit. __________ the fair pursued Her prattle, which on literature flowed ; Now changed her author, now her attitude, And much more symmetry than learning showed. Exdoxus watched her features, while they glowed, Till passion burst his puffy bosom's bound; And rescuing His cushion from its load, Flounced on his knees, appearing like a round Large fillet of hot veal just tumbled on the ground. 'Could such a lover be with scorn repulsed? Oh no! disdain befitted not the case; And Agnes at the sight was so convulsed That tears of Iaughter trickled down her face. Endoxus felt his folly and disgrace, Looked sheepish, nettled, or wished himself away; And thrice he tried to quit his kneeling place; But fat and corpulency seemed to say, Here's a petitioner that must for ever pray! The falling in love with a young lady at Lausanne is undoubtedly true; but it, happens that the incident took place in Gibbon's youth, when, so far from being fat or unwieldy, he was extremely slender-for, he it observed, the illustrious historian was in reality a small-boned man, and of more than usually slight figure in his young days. He was about twenty years of age, and was dwelling in Switzerland with a Protestant pastor by his father's orders, that he might recover himself (as he ultimately did) from a tendency to Romanism which had beset him at College, when Mademoiselle, Susan Curchod, the daughter of the pastor of Grassy in Burgundy, came on a visit to some relations in Lausanne. The father of the young lady, in the solitude of his village situation, had bestowed upon her a liberal education. 'She surpassed,' says Gibbon, 'his hopes, by her proficiency in the sciences and languages; and in her short visits to some relations at Lausanne, the wit, the beauty, and erudition of Mademoiselle Curchod were the theme of universal applause. The report of such a prodigy awakened my curiosity; I saw and loved. l found her learned without, pedantry, lively in conversation, pure in sentiment, and elegant in manners; and the first sudden emotion was fortified by the habits and knowledge of a more familiar acquaintance. She permitted me to make two or three visits at her father's house. I passed some happy days there in the mountains of Burgundy, and her parents honourably encouraged the connection. In a calm retirement, the vanity of youth no longer fluttered in her bosom; she listened to the voice of truth and passion, and I might presume to hope that I had made some impression on a virtuous heart. At Crassy and Lausanne, I indulged my dream of felicity; but, on my return to England, I soon found that my father would not hear of this strange alliance, and that without his consent I was myself destitute and helpless. After a painful struggle I yielded to my fate: I sighed as a lover, I obeyed as a son. My wound was insensibly healed by time, absence, and the habits of a new life. My cure was accelerated by a faithful report of the tranquillity and cheerfulness of the lady herself, and my love subsided into friendship and esteem.' The subsequent fate of Susan Curchod is worthy of being added. 'The minister of Grassy soon after died; his stipend died with him: his daughter retired to Geneva, where, by teaching young ladies, she earned a hard subsistence for herself and her mother; but in her lowest distress she maintained a spotless reputation and a dignified behaviour. A rich banker of Paris, a citizen of Geneva, had the good fortune and good sense to discover and possess this inestimable treasure; and in the capital of taste and luxury, she resisted the temptation of wealth, as she had sustained the hardships of indigence. The genius of her husband has exalted him to the most conspicuous situation in Europe. in every change of prosperity and disgrace, he has reclined on the bosom of a faithful friend; and Mademoiselle Curchod is now the wife of M. Necker, the Minister, and perhaps the Legislator, of the French monarchy.' Gibbon wrote: 'when the husband of his old love was trying to redeem France from destruction by financial reforms. Not long after, he and his family were obliged to fly from France, after which they spent several years in Switzerland. They were the parents of Madame de Stahl Holstein.' SIR JOHN MOOREThe battle of Corunna, January 16th, 1809, was heard of with profound feeling by the British public. An army had failed in its mission: deceived by the Spanish junta and British minister, it had made au advance on Madrid:, and was forced to commence a retreat in the depth of winter. But the commander, Sir John Moore, more than redeemed himself from any censure to which he was liable, by the skill and patience with which he conducted the troops on their withdrawal to the coast. Our army was in great wretchedness, but the pursuing French were worse; and when the gallant Moore stood at bay at Corunna, he gave the pursuers a thorough repulse, though at the expense of his own life.  The handsome and regular features of Moore bear a melancholy expression, in harmony with his fate. He was in reality an admirable soldier. he, had from boyhood devoted himself to his profession with extreme ardour, and his whole career was one in which duty was never lost sight of. He perished at the too early age of forty-seven, survived by his mother, at the mention of whose name, on his death-bed, he manifested the only symptom of emotion which escaped him in that trying hour. While a boy of eleven years old, Moore had a great advantage, for his education in matters of the world, by accompanying his father, Dr. Moore, on a tour of Europe, in company with the minor Duke of Hamilton, to whom Dr. Moore acted as governor or preceptor. The young soldier, constantly conversing with his highly enlightened parent, and introduced to many scenes calculated to awake curiosity, became a man in thoughts and manners while still a mere boy. At thirteen he danced, fenced, and rode with uncommon address. His character was a fine compound of intelligence, gentleness, and courage. The connection with the Duke of Hamilton had very nearly cost Moore his life. The Duke, though only sixteen, was allowed to wear a sword. One day, 'in an idle humour, he drew it, and began to amuse himself by fencing at young Moore, and laughed as he forced him to skip from side to side to shun false thrusts. The Duke continued this sport till Moore unluckily started in the line of the sword, and received it in his flank.' The elder Moore was speedily on the spot, and found his son wounded on the outside or the ribs. The incident led to the formation of a lasting friendship between the penitent young noble and his almost victim.-Life of Sir John Moore, by his brother, James Carrick Moore. THE BOTTLE HOAXOn the 16th of January 1749, there took place in London a bubble or hoax, which has somehow become unusually well impressed upon the publicmind. 'A person advertised that he would, this evening, at the Haymarket Theatre, play on a common walking cane the music of every instrument now used, to surprising perfection; that he would, on the stage, get into a tavern quart bottle, without equivocation, and while there, sing several songs, and suffer any spectator to handle the bottle; that if any spectator should come masked, he would, if requested, declare who they were; and that in a private room he would produce the representation of any person dead, with which the person requesting it should converse some minutes, as if alive.' The prices proposed for this show were-gallery, 2s.; pit, 3s.; boxes, 5s.; stage, 7s. 6d. At the proper time, the house was crowded with curious people, many of them of the highest rank, including no less eminent a person than the Culloden Duke of Cumberland. They sat for a little while with tolerable patience, though uncheered with music; but by and by, the performer not appearing, signs of irritation were evinced. In answer to a sounding with sticks and catcalls, a person belonging to the theatre came forward and explained that, in the event of a failure of performance, the money should be returned. A wag then cried out, that, if the ladies and gentlemen would give double prices, the conjurer would go into a pint bottle, which proved too much for the philosophy of the audience. A young gentleman threw a lighted candle upon the stage, and a general charge upon that part of the house followed. According to a private letter, to which we have had access-(it was written by a Scotch Jacobite lady) 'Cumberland was the first that flew in a rage, and called to pull down the house. He drew his sword, and was in such a rage, that somebody slipped in behind him and pulled the sword out of his hand, which was as much as to say, 'Fools should not have chopping sticks.' This sword of his has never been heard tell of, nor the person who took it. Thirty guineas of reward are offered for it. Monster of Nature, I am sure I wish he may never get it!' 'The greater part of the audience made their way out of the theatre; some losing a cloak, others a hat, others a wig, and others, hat, wig, and swords also. One party, however, stayed in the house, in order to demolish the inside; when, the mob breaking in, they tore up the benches, broke to pieces the scenes, pulled down the boxes, in short dismantled the theatre entirely, carrying away the particulars above-mentioned into the street, where they made a mighty bon-fire; the curtain being hoisted in the middle of it by way of flag.' There is a want of explanation as to the intentions of this conjurer. The proprietor of the theatre afterwards stated that, in apprehension of failure, he had reserved all the money taken, in order to give it back, and he would have returned it to the audience if they would have stayed their hands from destroying his house. It therefore would appear that either money was not the object aimed at, or, if aimed at, was not attained, by the conjurer. Most probably he only meant to try an experiment on the credulity of the public. The bottle hoax proved an excellent subject for the wits, particularly those of the Jacobite party. The following advertisement appeared in the paper called Old England: 'Found, entangled in a slit of a lady's demolished smock-petticoat, a gilt-handled sword of martial temper and length, not much the worse of wearing, with the Spey curiously engraven on one side, and the Scheid on the other; supposed to be taken from the fat sides of a certain great general in his hasty retreat from the battle of Bottle-noddles in the Haymarket. Whoever has lost it may inquire for it at the sign of the Bird and Singing Lane in Potters' Row.' |