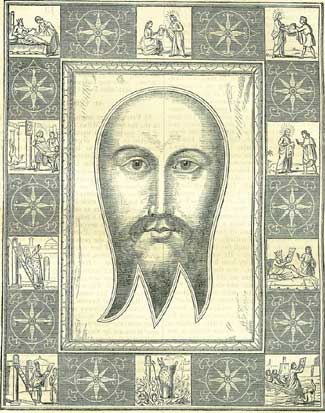

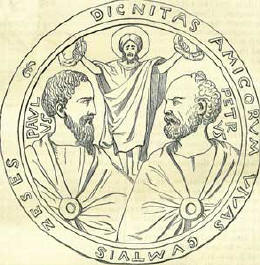

13th JanuaryBorn: Charles James Fox, statesman, 1748. Died: George Fox, founder of the sect of Quakers, 1690; Dr. James Macknight, 1800; Earl of Eldon (formerly Lord Chancellor of England), 1838. St. Kentigern (otherwise St. Mungo), of Glasgow, 601; St. Veronica of Milan, 1497. Feast Day: The 13th of January is held as St. Hilary's day by the Church of England. On this day, accordingly, begins the Hilary Term at Cambridge, though on the 14th at Oxford; concluding respectively on the Friday and Saturday next before Palm Sunday. ST. VERONICASt. Veronica was originally a poor girl working in the fields near Milan. The pious instructions of her parents fell upon a heart naturally susceptible in a high degree of religious impressions, and site soon became an aspirant for conventual life. Entering the nunnery of St. Martha in Milan, she in time became its superioress; in which position her conduct was most exemplary. Some years after her death, which took place in 1497, Pope Leo X allowed her to be honoured in her convent in the same manner as if she had been beatified in the usual form. Veronica appears as one whose mind had been wholly subdued to a religious life. She was evangelical perfection according to the ideas of her Church, and her age. Even under extreme and lingering sickness, she persisted in taking her share of the duties of her convent, submitting to the greatest drudgeries, and desiring to live solely on bread and water. 'Her silence was a sign of her recollection and continual prayer; in which her gift of abundant and almost continual tears was most wonderful. She nourished them by constant meditation on her own miseries, on the love of God, the joys of heaven, and the sacred passion of Christ. She always spoke of her own sinful life, as she called it, though it was most innocent, with the most profound compunction. She was favoured by God with many extraordinary visits and comforts.' The name Veronica conducts the mind back to a very curious, and very ancient, though obscure legend of the Romish Church. It is stated that the Saviour, at his passion, had his face wiped with a handkerchief by a devout female attendant, and that the cloth became miraculously impressed with the image of his countenance. It became Vera Iconica, or a true portrait of those blessed features. The handkerchief, being sent to Abgarus, king of Odessa, passed through a series of adventures, but ultimately settled at Rome, where it has been kept for many centuries in St. Peter's Church, under the highest veneration. There seems even to be a votive mass, 'de Sancta Veronica seu vultu Domini,' the idea being thus personified, after a manner peculiar to the ancient Church. From the term Vera Monica has come the name Veronica, the image being thus, as it were, personified in the character of a female saint, who, however, remains without biography and date. As a curiosity amongst ancient religious ideas, a picture of the revered hankerchief is here given.  From a series of papers contributed to the Journal for 1861, by Mr. Thomas Heaphy, artist London, entitled An Examination of the Antiquity of the Likeness of our Blessed Lord, it appears that the legendary portrait of Christ can be to traced with a respectable amount of evidence, much farther back than most persons are aware of. In the early days of the Christian Church at Rome, before it received the protection of the empire, the worshippers, rendered by their hopes of resurrection anxious to avoid burning the bodies of their friends, yet living amongst a people who burnt the dead and considered any other mode of disposing of them as a nuisance were driven the necessity of making subterranean excavations for purposes of sepulture, generally in secluded grounds belonging to rich. individuals. Hence the famous Catacombs of Rome, dark pas-ages in the rock, sometimes three above each other, having tiers of recesses for bodies along their sides, and all wonderfully well preserved. In these recesses, not unfrequently, the remains of bodies exist; in many, there are tablets telling containing lachrymatories, or tear-vials, and little glass vessels, the sacramental cups of the primitive church, on which may still be traced pictures of Christ and his principal disciples. A vast number, however, of these curious remains have been transferred to the Vatican, where they are guarded with the most jealous care. Mr. Heaphy met with extraordinary difficulties in his attempts to examine the Catacombs, and scarcely less in his endeavours to see the stores of reliques in the Vatican. He has nevertheless placed before us a very interesting series of the pictures found, generally wrought in gold, on the glass cups above adverted to.  Excepting in one instance, where Christ is represented in the act of raising Lazarus from the dead (in which case the face is an ordinary one with a Brutus crop of hair), the portrait of Jesus is invariably represented as that peculiar oval one, with parted hair, with which we are so familiar; and the fact becomes only the more remarkable from the contrast it presents to other faces, as those of St. Peter or St. Paul, which occur in the same pictures, and all of which have their own characteristic forms and expressions. Now, Tertullian, who wrote about the year 160, speaks of these portraits on sacramental vessels as a practice of the: first Christians, as if it were, even in his time, a thing of the past. And thus the probability of their being found very soon after the time of Christ, and when the tradition of his personal appearance was still fresh, is, in Mr. Heaphy's opinion, established. We are enabled here to give a specimen of these curious illustrations of early Christianity, being one on which Mr. Heaphy makes the following remarks: 'An instance of what may be termed the transition of the type, being apparently executed at a time when some information respecting the more obvious traits in the true likeness had reached Rome, and the artist felt no longer at liberty to adopt the mere conventional type of a Roman youth, but aimed at giving such distinctive features to the portrait as he was able from the partial information which had reached him. We see in this instance that our Saviour, who is represented as giving the crown of life to St. Peter and St. Paul, is delineated with the hair divided in the middle (distinctly contrary to the fashion of that day) and a beard, being so far an approximation to the true type. One thing to be specially noticed is, that the portraits of the two apostles were at that time already depicted under an easily recognized type of character, as will be seen by comparing this picture with two others which will appear hereafter, in all of which the short, curled, bald head and thick-set features of St. Peter are at once discernible, and afford direct evidence of its being an exact portrait likeness, [while] the representation of St. Paul is scarcely less characteristic.' ST. KENTIGERNOut of the obscurity which envelopes the history of the northern part of our island in the fifth and sixth centuries, when all of it that was not provincial Roman was occupied by Keltic tribes under various denominations, there loom before us three holy figures, engaged in planting Christianity. The first of these was Ninian, who built a church of stone at Whithorn, on the promontory of Wigton; another was Serf, who some time after had a cell at Culross, on the north shore of the Firth of Forth; a third was Kentigern, pupil of the last, and more notable than either. He appears to have flourished through-out the sixth century, and to have died in 601. Through his mother, named Thenew, he was connected with the royal family of the Cumbrian Britons-a rude state stretching along the west side of the island between Wales and Argyle. After being educated by Serf at Culross, he returned among his own people, and planted a small religious establishment on the banks of a little stream which falls into the Clyde at what is now the city of Glasgow. Upon a tree beside the clearing in the forest, he hung his bell to summon the savage neighbours to worship; and the tree with the bell still figures in the arms of Glasgow. Thus was the commencement made of what in time became a seat of population in connection with an Episcopal see; by and by, an industrious town; ultimately, what we now see, a magnificent city with half a million of inhabitants. Kentigern, though his amiable character procured him the name of Mungo, or the Beloved, had great troubles from the then king of the Strathclyde Britons; and at one time he had to seek a refuge in Wales, where, however, he employed himself to some purpose, as he there founded, under the care of a follower, St. Asaph, the religious establishment of that name, now the seat of an English bishopric. Resuming his residence at Glasgow, he spent many years in the most pious exercises-for one thing reciting the whole psalter once every day. As generally happened with those who gave themselves up entirely to sanctitude, he acquired the reputation of being able to effect miracles. Contemporary with him, though a good deal his junior, was St. Columba, who had founded the celebrated monastery of I-coin-kill. It is recorded that Columba came to see St. Kentigern at his little church beside the Clyde, and that they interchanged their respective pastoral staves, as a token of brotherly affection. For a time, these two places were the centres of Christian missionary exertion in the country now called Scotland. St. Kentigern, at length dying at an advanced age, was buried on the spot where, five centuries afterwards, arose the beautiful cathedral which still bears his name. CHARLES JAMES FOX Of Charles James Fox, the character given by his friends is very attractive: 'He was,' says Sir James Mackintosh, 'gentle, modest, placable, kind, of simple manners, and so averse from parade and dogmatism, as to be not only unostentatious, but even somewhat inactive in conversation. His superiority was never felt, but in the instruction which he imparted, or in the attention which his generous preference usually directed to the more obscure members of the company. His conversation, when it was not repressed by modesty or indolence, was delightful. The pleasantry, perhaps, of no man of wit had so unlaboured an appearance. It seemed rather to escape from his mind than to be produced by it. His literature was various and elegant. In classical erudition, which, by the custom of England, is more peculiarly called learning, he was inferior to few professed scholars. Like all men of genius, he delighted to take refuge in poetry, from the vulgarity and irritation of business. His own verses were easy and pleasing, and might have claimed no low place among those which the French call vers de société. He disliked political conversation, and never willingly took any part in it. From these qualities of his private as well as from his public character, it probably arose that no English statesman ever preserved, during so long a period of adverse fortune, so many affectionate friends, and so many zealous adherents.' The shades of Fox's history are to be found in his extravagance, his gambling habits (which reduced him to the degradation of having his debts paid by subscription), and his irregular domestic life; but how shall the historian rebuke one whose friends declared that they found his faults made him only the more lovable? Viewing the unreasonableness of many party movements and doings, simply virtuous people sometimes feel inclined to regard party as wholly opposed in spirit to truth and justice. Hear, however, the defence put forward for it by the great Whig leader: 'The question,' says he, 'upon the solution of which, in my opinion, principally depends the utility of party, is, in what situations are men most or least likely to act corruptly-in a party, or insulated? and of this I think there can be no doubt. There is no man so pure who is not more or less influenced, in a doubtful case, by the interests of his fortune or his ambition. If, therefore, a man has to decide upon every new question, this influence will have so many frequent opportunities of exerting itself that it will in most cases ultimately prevail; whereas, if a man has once engaged in a party, the occasions for new decisions are more rare, and consequently these corrupt influences operate less. This reasoning is much strengthened when you consider that many men's minds are so framed that, in a question at all dubious, they are incapable of any decision; some, from narrowness of understanding, not seeing the point of the question at all; others, from refinement, seeing so much on both sides, that they do not know how to balance the account. Such persons will, in nine cases out of ten, be influenced by interest, even without their being conscious of their corruption. In short, it appears to me that a party spirit is the only substitute that has been found, or can be found, for public virtue and comprehensive understanding; neither of which can be reasonably expected to be found in a very great number of people. Over and above all this, it appears to me to be a constant incitement to everything that is right: for, if a party spirit prevails, all power, aye, and all rank too, in the liberal sense of the word, is in a great measure elective. To be at the head of a party, or even high in it, you must have the confidence of the party; and confidence is not to be procured by abilities alone. In an Epitaph upon Lord Rockingham, written I believe by Burke, it is said, 'his virtues were his means;' and very truly; and so, more or less, it must be with every party man. Whatever teaches men to depend upon one another, and to feel the necessity of conciliating the good opinion of those with whom they live, is surely of the highest advantage to the morals and happiness of mankind; and what does this so much as party? Many of these which. I have mentioned are only collateral advantages, as it were, belonging to this system; but the decisive argument upon this subject appears to me to be this: Is there any other mode or plan in this country by which a rational man can hope to stem the power and influence of the Crown? I am sure that neither experience nor any well-reasoned theory has ever shewn any other. Is there any other plan which is likely to make so great a number of persons resist the temptations of titles and emoluments? And if these things are so, ought we to abandon a system from which so much good has been derived, because some men have acted inconsistently, or because, from the circumstances of the moment, we are not likely to act with much effect?' Mr. Fox was the third son of Henry Fox, afterwards Lord Holland, and of Lady Georgina Caroline Fox, eldest daughter of Charles, second Duke of Richmond. As a child he was remarkable for the quickness of his parts, his engaging disposition, and early intelligence. 'There's a clever little boy for you!' exclaims his father to Lady Caroline Fox, in repeating a remark made a propos by his son Charles, when hardly more than two years and a half old. 'I dined at home to-day,' he says, in another letter to her, 'tete-a-tote with Charles, intending to do business, but he has found me pleasanter employment, and was very sorry to go away so soon.' He is, in another letter, described as 'very pert, and very argumentative, all life and spirits, motion, and good humour; stage-mad, but it makes him read a good deal.' That he was excessively indulged is certain: his father had promised that he should be present when a garden wall was to be flung down, and having forgotten it, the wall was built up again-it was said, that he might fulfil his promise. DR. MACKNIGHTDr. James Macknight, born in 1721, one of the ministers of Edinburgh, wrote a laborious work on the Apostolical Epistles, which was published in 1795, in four volumes 4 to. He had worked at it for eleven hours a day for a series of years, and, though. well advanced in life, maintained tolerable health of body and mind through these uncommon labours; but no sooner was his mind relieved of its familiar task, than its powers, particularly in the department of memory, sensibly began to give way; and the brief remainder of his life was one of decline. Dibdin recommends the inviting quartos of Macknight, as containing 'learning without pedantry, and piety without enthusiasm.' A SERMON BY THE POPEIt is a circumstance not much known in Protestant countries, that the head of the Roman Catholic Church does not ascend the pulpit. Whether it is deemed a lowering of dignity for one who is a sovereign prince as well as a high priest to preach a sermon like other priests, or whether he has not time-certain it is that priests cease to be preachers when they become popes. One single exception in three hundred years tends to illustrate the rule. The present pope, Pius IX, has supplied that exception. It has been his lot to be, and to do, and to see many things that lie out of the usual path of pontiff's, and this among the number. On the 2nd of June 1846, Pope Gregory XVI died. Fifty - one cardinals assembled at the palace of the Quirinal at Rome, on Sunday the 14th, to elect one of their body as a successor to Gregory. The choice fell on Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti, Cardinal-Archbishop of Imola; and he ascended the chair of St. Peter as Pope Pius IX. He was a liberal man, who had won much popular esteem by his general kindness, especially to the poor and afflicted. While yet an archbishop, he occupied the pulpit one day in an unexpected manner; the officiating priest was taken ill during his sermon, and the cardinal, who was present, at once took his place, his text, and his line of argument. It was equally an unforeseen incident for him to preach as a pope. The matter is thus noticed in Count de Liancourt's Pius the Ninth: the First Year of his Poutificate, under the date January 13th, 1847: 'This circumstance has been noticed in the chronological tables of the year as an event which had not occurred before for three hundred years. But it is as well that it should be known that it was not a premeditated design on the part of his Holiness, but merely the result of accident. On the day in question, the Octave of the Epiphany, the celebrated preacher Padre Ventura, whose eloquence attracted crowds of eager listeners, had not arrived at the church (de Santa Andrea della Valle, at Rome); and the disappointed congregation, thinking indisposition was the cause of his absence, were on the point of retiring, when suddenly the bells rang, and announced the unexpected arrival of the Sovereign Pontiff. It is impossible to describe the feelings of the congregation, or the deep interest and excitement which were produced in their minds when they saw Pius IX. advance towards the pulpit, or the profound silence with which they listened to his discourse.' It was a simple, good, plain sermon, easily intelligible to all. This was a day to be remembered, for Pius IX was held almost in adoration at that time by the excitable Italians. He was a reforming pope, a liberal pope. He offended Austria and all the petty despots of Italy by his measures as an Italian prince, if not as the head of the Church. He liberated political prisoners; gave the first sign of encouragement to the construction of railways in the papal dominions; gave increased freedom to the press; encouraged scientific meetings and researches; announced his approval of popular education; surrounded him-self with liberal ministers; and purified the papal household. It was hard work for him to contend against the opposition of Lambruschini and other cardinals; but he did so. Alas! it was all too good to be permanent. The year 1818 arrived, and with it those convulsions which agitated almost every country in Europe. Pope Plus became thoroughly frightened. He either really believed that nations are not fitted for so much liberty and liberalism as he had hitherto been willing to give them, or else the power brought to bear against him by emperors, kings, princes, grand - dukes, cardinals, and arch-bishops, was greater than he could withstand. He changed his manners and proceedings, and became like other popes. What followed all this, belongs to the history of Italy. THE CHANGE OF THE STYLE IN BRITAINThe Act for the change of the style (24 Geo. II. cap. 23) provided that the legal year in England 1752 should commence, not on the 25th of March, but on the 1st of January, and that after the 3rd of September in that year, the next ensuing day should be held as the 14th, thus dropping out eleven days. The Act also included provisions regarding the days for fairs and markets, the periods of legal obligations, and the future arrangements of the calendar. A reformed plan of the calendar, with tables for the moveable feasts, he. occupies many pages of the statute. The change of the style by Pope Gregory in the sixteenth century was well received by the people of the Catholic world. Miracles which took place periodically on certain days of the year, as for example the melting of the blood of St. Gennaro at Naples on the 19th of September, observed the new style in the most orthodox manner, and the common people hence concluded that it was all right. The Protestant populace of England, equally ignorant, but without any such quasi-religious principle to guide them, were, on the contrary, violently inflamed against the statesmen who had carried through the bill for the change of style; generally believing that they had been defrauded of eleven days (as if eleven days of their destined lives) by the trans-action. Accordingly, it is told that for some time afterwards, a favourite opprobrious cry to unpopular statesmen, in the streets and on the hustings, was, 'Who stole the eleven days? Give us back the eleven days!' Near Malwood Castle, in Hampshire, there was an oak tree which was believed to bud every Christmas, in honour of Him who was born on that day. The people of the neighbourhood said they would look to this venerable piece of timber as a test of the propriety of the change of style. They would go to it on the new Christmas Day, and see if it budded: if it did not, there could be no doubt that the new style was a monstrous mistake. Accordingly, on Christmas Day, new style, there was a great flocking to this old oak, to see how the question was to be determined. On its being found that no buddling took place, the opponents of the new style triumphantly proclaimed that their view was approved by Divine wisdom-a point on which it is said they became still clearer, when, on the 5th January, being old Christmas Day, the oak was represented as having given forth a few shoots. These people were unaware that, even although there were historical grounds for believing that Jesus was born on the 25th of December, we had been carried away from the observance of the true day during the three centuries which elapsed between the event and the Council of Nice. The change of style has indeed proved a sad discomfiture to all ideas connected with particular days and seasons. It was said, for instance, that March came in like a lion and went out like a lamb; but the end of the March of which this was said, is in reality the 12th of April. Still more absurd did it become to hold All Saints' Eve (October 31st) as a time on which the powers of the mystic world were in particular vigour and activity, seeing that we had been observing it at a wrong time for centuries. We had been continually for many centuries gliding away from the right time, and yet had not perceived any difference-a pretty good proof that the assumedly sacred character of the night was all empty delusion. RECOVERED RINGSIn the Acla Sanatorium a curious legend is related in connection with the life of Kentigern, as to the finding of a lost ring. A queen, having formed an improper attachment to a handsome soldier, put upon his finger a precious ring which her own lord had conferred upon her. The king, made aware of the fact, but dissembling his anger, took an opportunity, in hunting, while the soldier lay asleep beside the Clyde, to snatch off the ring, and throw it into the river. Then returning home along with the soldier, he demanded of the queen the ring he had given her. She sent secretly to the soldier for the ring, which could not be restored. In great terror, she then dispatched a messenger to ask the assistance of the holy Kentigern. He, who knew of the affair before being informed of it, went to the river Clyde, and having caught a salmon, took from its stomach the missing ring, which he sent to the queen. She joyfully went with it to the king, who, thinking he had wronged her, swore he world be revenged upon her accusers; but she, affecting a forgiving temper, besought him to pardon them as she had done. At the same time, she confessed her error to Kentigern, and solemnly vowed to be more careful of her conduct in future.'' In the armorial bearings of the see of Glasgow, and now of the city, St. Kentigern's tree with its bell forms the principal object, while its stem is crossed by the salmon of the legend, bearing in its mouth the ring so miraculously recovered.  Fabulous as this old church legend may appear, it does not stand quite alone in the annals of the past. In Brand's History of Newcastle, we find the particulars of a similar event which occurred at that city in or about the year 1559. A gentleman named Anderson-called in one account Sir Francis Anderson-fingering his ring as he was one day standing on the bridge, dropped the bauble into the Tyne, and of course gave it up as lost. After some time a servant of this gentleman bought a fish in Newcastle market, in the stomach of which the identical lost ring was found. An occurrence remarkably similar to the above is related by Herodotus as happening to Polycrates, after his great success in possessing himself of the island of Samos. Amasis, king of Egypt, sent Poly crates a friendly letter, ex-pressing a fear for the continuance of his singular prosperity, for he had never known such an instance of felicity which did not come to calamity in the long run; therefore advising Polycrates to throw away some favourite gem in such a way that he might never see it again, as a kind of charm against misfortune. Polycrates consequently took a valuable signet-ring-an emerald set in gold-and sailing away from the shore in a boat, threw this gem, in the sight of all on board, into the deep.' This done, he returned home and gave vent to his sorrow. 'Now it happened, five or six days afterwards, that a fisherman caught a fish so large and beautiful that he thought it well deserved to be made a present of to the king. So he took it with him to the gate of the palace, and said that he wanted to see Polycrates. Then Polycrates allowed him to come in, and the fisherman gave him the fish with these words following: 'Sir king, when I took this prize, I thought I would not carry it to market, though I am a poor man who live by my trade. I said to myself, it is worthy of Polycrates and his greatness; and so I brought it here to give it you.' The speech pleased the king, who thus spoke in reply: 'Thou didst well, friend, and I am doubly indebted, both for the gift and for the speech. Come now, and sup with me.' So the fisherman went home, esteeming it a high honour that he had been asked to sup with the king. Meanwhile, the servants, on cutting open the fish, found the signet of their master in its belly. No sooner did they see it than they seized upon it, and hastening to Polycrates with great joy, restored it to him, and told him in what way it had been found. The king, who saw something providential in the matter, forthwith wrote a letter to Amasis, telling him all that had happened. . . . Amasis . . . perceived that it does not belong to man to save his fellowman from the fate which is in store for him; likewise he felt certain that Polycrates would end ill, as he prospered in everything, even finding what he had thrown away. So he sent a herald to Samos, and dissolved the contract of friendship. This he did, that when the great and heavy misfortune came, he might escape the grief which he would have felt if the sufferer had been his loved friend.' In Scottish family history there are at least two stories of recovered rings, tending to support the possible verity of the Kentigern legend. The widow of Viscount Dundee-the famous Claverhouse-was met and wooed at Colzium House, in Stirlingshire, by the Hon William Livingstone, who subsequently became Viscount Kilsyth. The gentleman gave the lady a pledge of affection in the form of a ring, having for its posy, 'YOURS ONLY AND EVER.' She unluckily lost it in the garden, and it could not again be found; which was regarded as an unlucky prognostic for the marriage that soon after took place. Nor was the prognostic falsified by the event, for not long after her second nuptials, while living in exile in Holland, she and her only child were killed by the fall of a house. Just a hundred years after, the lost ring was found in a clod in the garden; and it has since been preserved at Colzium House. The other story is less romantic, yet curious, and of assured verity. A large silver signet ring was lost by Mr. Murray of Pennyland, in Caithness, as he was walking one day on a shingly beach bounding his estate. Fully a century afterwards, it was found in the shingle, in fair condition, and restored to Mr. Murray's remote heir, the present Sir Peter Murray Threipland of Fingask, baronet. Professor De Morgan, in Notes and Queries for December 21, 1861, relates an anecdote of a recovered ring nearly as wonderful as that connected with the life of Kentigern. He says he does not vouch for it; but it was circulated and canvassed, nearly fifty years ago, in the country town close to which the scene is placed, with all degrees of belief and unbelief. 'A servant boy was sent into the town with a valuable ring. He took it out of its box to admire it, and in passing over a plank bridge he let it fall on a muddy bank. Not being able to find it, he ran away, took to the sea, finally settled in a colony, made a large fortune, came back after many years, and bought the estate on which he had been servant. One day, while walking over his land with a friend, he came to the plank bridge, and there told his friend the story. 'I could swear,' said he, pushing his stick into the mud, 'to the very spot on which the ring dropped.' When the stick came back the ring was on the end of it.' WILD OATSWe are more familiar with wild oats in a moral than in a botanical sense; yet in the latter it is an article of no small curiosity. For one thing, it has a self-inherent power of moving from one place to another. Let a head of it be laid down in a moistened state upon a table, and left there for the night, and next morning it will be found to have walked off. The locomotive power resides in the peculiar hard awn or spike, which sets the grain a-tumbling over and over, sideways. A very large and coarse kind of wild oats, brought many years ago from Otaheite, was found to have the ambulatory character in uncommon perfection. When ordinary oats is allowed by neglect to degenerate, it acquires this among other characteristics of wild oats. |