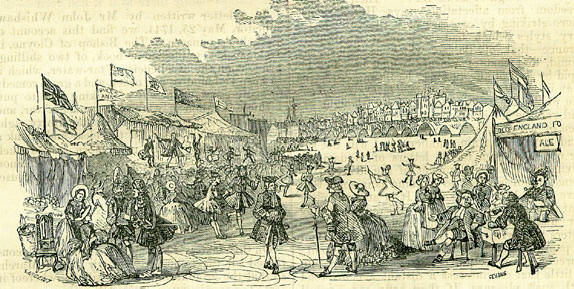

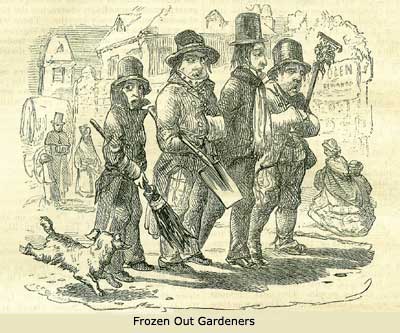

14th JanuaryBorn: Prince Adam Czartoryski, 1770. Died: Edward Lord Bruce, 1610; Dr. John Boyse, translator of the Bible, 1643; Madame de Sevigné, 1696; Edmund Halley, astronomer, 1742; Dr. George Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne, 1753. Feast Day: Sts. Isaias and Sabbas, 273. St. Barbasceminus, 346. St. Hilary, B. 368. St. Felix. ST. HILARYSt. Hilarius lived in the fourth century, and the active and influential part of his life was passed under the Emperor Constantius in the East, though he is included among the Fathers of the Western or Latin Church. He belonged to a family of distinction resident at Poitiers, in Gaul, and was brought up in paganism, but became a convert to Christianity, and in the year 354 was elected bishop of Poitiers. The first general council, held at Nice (Nicaea) in Bithynia, in 325, under the Emperor Constantine, had condemned the doctrine of Arius, but had not suppressed it; and Hilarius, about thirty years afterwards, when he had made himself acquainted with the arguments, became an opponent of the Arians, who were then numerous, and were patronised by the Emperor Constantius. The council of Arles, held in 353, had condemned Athanasius and others, who were opponents of the Arian doctrine; and Hilarius, in the council of Beziers, held in 356, defended Athanasius, in opposition to Saturninus, bishop of Arles. He was in consequence deposed from his bishopric by the Arians, and banished by Constantius to Phrygia. There he remained about four years, occupied in composing his principal work, On the Trinity, in twelve books. Hilarius, besides his twelve books On the Trinity, wrote a work On Synods addressed to the bishops of Gaul and Britain, in which he gives an account of the various creeds adopted in the Eastern church subsequent to the council of Nice; and he addressed three books to the Emperor Constantius, of whose religious opinions he was always an energetic and fearless opponent. He continued, indeed, from the time when he became a bishop till the termination of his life in 368, to be zealously engaged in the Trinitarian controversy; and the final triumph of the Nicene creed over the Arian may be attributed in a great degree to his energetic exertions. After the death of Constantius, in 361, he was restored to his bishopric, and returned to Poitiers, where he died. DR. JOHN BOYSEA minute and interesting memoir of this eminent scholar, in Peck's Desiderata Curiosa makes us aware of his profound learning, his diligence in study, and his many excellences of character. Ultimately he was a prebendary of Ely; but when engaged in his task of translating the Bible, he was only rector of Boxworth. Boyse was one of a group of seven scholars at Cambridge to whom were committed the Apocryphal books; and when, after four years, this task was finished, he was one of two of that group sent to London to superintend the general revision. With other four learned men, Boyse was engaged for nine months at Stationers' Hall, in the business of revising the entire translation; and it is not unworthy of notice, as creditable to the trade of literature, that, while the task of translation passed unrewarded of the nation, that of revision was remunerated by the Company of Stationers sending each scholar thirty shillings a week. The idea of a guerdon for literary exertion was then a novelty-indeed a thing scarcely known in England. Boyse was employed with Sir Henry Savile in that serious task of editing Chrysostom, which led to a celebrated witticism on the part of Sir Henry. Lady Savile, complaining one day to her husband of his being so abstracted from her society by his studies, expressed a wish that she were a book, as she might then receive some part of his attention. 'Then,' said Sir Henry, 'I should have you to be an almanack, that I might change you every year.' She threatened to burn Chrysostom, who seemed to be killing her husband; whereupon Dr. Boyse quietly remarked, 'That were a great pity, madam.' 'Why, who was Chrysostom?' inquired she. 'One of the sweetest preachers since the Apostles' times,' he calmly answered. 'Then,' said she, corrected by his manner and words, 'I would not burn him for the world.' Boyse lived to eighty-two, though generally engaged eight hours a day in study. He seems to have been wise before his time as to the management of his physical system under intellectual labour, and his practice may even yet be described with advantage. 'He made but two meals, dinner and supper; betwixt which he never so much as drank, unless, upon trouble of flatulency, some small quantity of aqua-vitae and sugar. After meat he was careful, almost to curiosity, in picking and rubbing his teeth; esteeming that a special preservative of health; by which means he carried to his grave almost a Hebrew alphabet of teeth [twenty-two]. When that was done, he used to sit or walk an hour or more, to digest his meat, before he would go to his study. . . . He would never study at all, in later years, between supper and bed; which time, two hours at least, he would spend with his friends in discourse, hearing and telling harmless, delightful stories, whereof he was exceedingly full. . . . The posture of his body in studying was always standing, except when for ease he went upon his knees.' No modern physiologist could give a better set of rules than these for a studious life, excepting as far as absence of all reference to active exercise is concerned. MADAME DE SEVIGNÉThis celebrated woman, who has the glory of being fully as conspicuous in the graces of style as any writer of her age, died. after a few days' illness, at the town of Grignan. Her children were throughout life her chief object, and especially her daughter, to her affliction for whom we owe the greater part of that admirable collection of Letters upon which the fame of Madame de Sevigné is raised. La Harpe describes them as: 'the book of all hours, of the town, of the country, on travel. They are the conversations of a most agreeable woman. to which one need contribute nothing but one's own; which is a great charm to an idle person.' Her Letters were not published till the eighteenth century, but they were written in the mid-day of the reign of Louis XIV. 'Their ease and freedom from affectation,' says Hallam, 'are more striking by contrast with the two epistolary styles which had been most admired in France-that of Balzac, which is laboriously tumid, and that of Voiture, which: becomes insipid by dint of affectation. Everyone perceives that in the letters of a Mother to her Daughter, the public, in a strict sense, is not thought of; and yet the habit of speaking and writing what men of wit and taste would desire to hear and read, gives a certain mannerism, I will not say air of effort, even to the letters of Madame de Sevigné. The abandonment of the heart to its casual impulses is not so genuine as in some that have since been published. It is at least clear that it is possible to become affected in copying her unaffected style; and some of Walpole's letters bear witness to this. Her wit and talent of painting by single touches are very eminent; scarcely any collection of letters, which contain so little that can interest a distant age, are read with such pleasure. If they have any general fault, it is a little monotony and excess of affection towards her daughter, which is reported to have wearied its object, and, in contrast with this, a little want of sensibility towards all beyond her immediate friends, and a readiness to find something ludicrous in the dangers and sufferings of others.' Thus, in one letter she mentions that a lady of her acquaintance, having been bitten by a mail doe had gone to be dipped in the sea. and amuses herself by taking off the provincial accent with which. she will express herself on the first plunge. She makes a jest of La Voisin's execution, and thought that person was as little entitled to sympathy as any one; yet, when a woman is burned alive, it is not usual for another woman to turn it into drollery.-Literature of Europe. Madame de Sevignés taste has been arraigned for slighting Racine; and she has been charged with the unfortunate prediction: 'Il passera comme café.' But it has been denied that these words can be found, though few like to give up so diverting a miscalculation of futurity. BISHOP BERKELEY AND TARWATERBerkeley was a poet, as well as a mathematician and philosopher; and his mind was not only well stored with professional and philosophical learning, but with information upon trade, agriculture, and the common arts of life. Having received benefit from the use of tar-water, when ill of the colic, he published a work on the Virtues of Tar-water, on which he said he had bestowed more pains than on any other of his productions. His last work, published but a few mouths before his death, was Further Thoughts on Tar-water; and it shows his enthusiastic character, that, when accused of fancying he had discovered a panacea in tar-water, he replied, that to speak out, he freely owns he suspects tar-water is a panacea.' Walpole has taken the trouble to preserve, from the newspapers of the day, the following epigram on Berkeley's tar-water: Who dare deride what pious Cloyne has done? The Church shall rise and vindicate her son; She tells is all her bishops shepards are, And Shepherds heal their rotten sheep with tar In a letter written by Mr. John Whishaw, solicitor, May 25th, 1744, we find this account of Berkeley's panacea: 'The Bishop of Cloyne, in Ireland, has published a book, of two shillings price, upon the excellencies of tar-water, which is to keep ye bloud in due order, and a great remedy in many cases. His way of making it is to put, I think a gallon of water to a quart of tar, and after stirring it together. to let it stand forty-eight hours, and then pour off the clear and drink a glass of about half a pint in ye mornn, and as much at five in ye afternoon. So it's become common to call for a glass of tar-water in a coffee-house, as a dish of tea or coffee.' GREAT FROSTSOn this day in 1205: 'began a frost which continued till the two and twentieth day of March, so that the ground could not be tilled; whereof it came to pass that, in summer following a quarter of wheat was sold for a mark of silver in many places of England, which for the more part in the days of King Henry the Second was sold for twelve pence; a quarter of beans or peas for half a mark; a quarter of oats for thirty pence, that were wont to be sold for fourpence. Also the money was so sore clipped that there was no remedy but to have it renewed.' It has become customary in England to look to St. Herilary's Day as the coldest in the year; perhaps from its being a noted day about the middle of the noted coldest month. It is, however, just possible that the commencement of the extraordinary and fatal frost of 1205, on this day, may have had something to do with the notion; and it may be remarked, that in 1820 the 14th of January was the coldest day of the year, one gentleman's thermometer falling to four degrees Fahrenheit below zero. On a review of the greatest frosts in the English chronicles, it can only be observed that they have for the most part occurred throughout January, and only, in general, diverge a little into December on the one hand, and February on the other. Yet one of the most remarkable of modern frosts began quite at the end of January. It was at that time in 1814 that London last saw the Thames begin to be so firmly frozen as to support a multitude of human beings on its surface. For a month following the 27th of the previous December, there had been a strong frost in England. A thaw took place on the 26th January, and the ice of the Thames came down in a huge 'pack,' which was suddenly arrested between the bridges by the renewal of the frost. On the 31st the ice pack was so firmly frozen in one mass, that people began to pass over it, and next day the footing appeared so safe, that thousands of persons ventured to cross.  Opposite to Queen-hithe, where the mass appeared most solid, upwards of thirty booths were erected, for the sale of liquors and viands, and for the playing of skittles. A sheep was set to a fire in a tent upon the ice, and sold in shilling slices, under the appellation of Lapland mutton. Musicians came, and dances were effected on the rough and slippery surface. What with the gay appearance of the booths, and the quantity of favourite popular amusements going on, the scene was singularly cheerful and exciting. On the ensuing day, faith in the ice having increased, there were vast multitudes upon it between the London and Blackfriars' Bridges; the tents for the sale of refreshments, and for games of hazard, had largely multiplied; swings and merry-go-rounds were added to skittles; in short, there were all the appearances of a Greenwich or Bartholomew Fair exhibited on this frail surface, and Frost Fair was a term in everybody's mouth. Amongst those who strove to make a trade of the occasion, none were more active than the humbler class of printers. Their power of producing an article capable of preservation, as a memorial of the affair, brought them in great numbers to the scene. Their principal business consisted, accordingly, in the throwing off of little broadsides referring to Frost Fair, and stating the singular circumstances under which they were produced, in rather poor verses-such as the following: Amidst the arts which on the Thames appear, To tell the wonders of this icy year, Printing claims prior place, which at one view Erects a monument of THAT and You. Another peculiarly active corps was the ancient fraternity of watermen, who, deserting their proper trade, contrived to render themselves serviceable by making convenient accesses from the landings, for which they charged a moderate toll. It was reported that some of these men realized as much as ten pounds a day by this kind of business. All who remember the scene describe it as having been singular and picturesque. It was not merely a white icy plain, covered with flag-bearing booths and lively crowds. The peculiar circumstances under which this part of the river had finally been frozen, caused it to appear as a variegated ice country-hill and dale, and devious walk, all mixed together, with human beings thronging over every bit of accessible surface. After Frost Fair had lasted with increasing activity for four days, a killing thaw came with the Saturday, and most of the traders who possessed any prudence struck their flags and departed. Many, reluctant to go while any customers remained, held on past the right time, and towards evening there was a strange medley of tents, and merry-go-rounds, and printing presses seen floating about on detached masses of ice, beyond recovery of their dismayed owners, who had themselves barely escaped with life. A large refreshment booth, belonging to one Lawrence, a publican of Queenhithe, which had been placed opposite Brook's Wharf, was floated off by the rising tide, at an early hour on Sunday morning, with nine men in the interior, and was borne with violence back towards Blackfriars' Bridge, catching fire as it went. Before the conflagration had gone far, the whole mass was dashed to pieces on one of the piers of the bridge, and the men with difficulty got to land. A vast number of persons suffered immersion both on this and previous days, and three men were drowned. By Monday nothing was to be seen where Frost Fair had been, but a number of ice-boards swinging lazily backwards and for-wards under the impulse of the tide. There has been no recurrence of Frost Fair on the Thames from 1814 down to the present year (1861); but it is a phenomenon which, as a rule, appears to recur several times each century. The next previous occasion was in the winter of 1788-9; the next again in January 1740, when people dwelt in tents on the Thames for weeks. In 1715-16, the river was thickly frozen for several miles, and became the scene of a popular fete resembling that just described, with the additional feature of an ox roasted whole for the regalement of the people. The next previous instance was in January 1684. There was then a constant frost of seven weeks, producing ice eighteen inches thick. A contemporary, John Evelyn, who was an eyewitness of the scene, thus describes it: 'The frost continuing, more and more severe, the Thames, before London, was still planted with booths in formal streets, all sorts of trades and shops, furnished and full of commodities, even to a printing press, where the people and ladies took a fancy to have their names printed, and the day and the year set down when produced on the Thames: this humour took so universally, that it was estimated the printer gained five pounds a day, for printing a line only, at sixpence a name, besides what he got by ballads, &c. Coaches plied from Westminster to the Temple and from other stairs, to and fro, as in the streets; sheds, sliding with skates, or bull-baiting, horse and coach races, puppet-shows and interludes, cooks, tippling and other lewd places; so that it seemed to be a bacchanalian triumph or carnival on the water: while it was a severe judgment on the land, the trees not only splitting as if lightning-struck, but men and cattle perishing in divers places, and the very seas so locked up with ice, that no vessels could stir out or come in; the fowls, fish, and birds, and all our exotic plants and greens, universally perishing. Many parks of deer were destroyed; and all sorts of fuel so dear, that there were great contributions to keep the poor alive. Nor was this severe weather much less intense in most parts of Europe, even as far as Spain in the most southern tracts. London, by reason of the excessive coldness of the air hindering the ascent of the smoke, was so filled with the fuliginous stream of the sea-coal, that hardly could any one see across the streets; and this filling of the lungs with the gross particles exceedingly obstructed the breath, so as one could scarcely breathe. There was no water to be had from the pipes or engines; nor could the brewers and divers other tradesmen work; and every moment was fall of disastrous accidents.' Hollinshed describes a severe frost as occurring at the close of December 1564: 'On New Year's even,' he says, 'people went over and along the Thames on the ice from London Bridge to Westminster. Some played at the foot-ball as boldly there as if it had been on dry land. Divers of the court, being daily at Westminster, shot daily at pricks set upon the Thames; and the people, both men and women, went daily on the Thames in greater number than in any street of the city of London. On the 3rd day of January it began to thaw, and on the 5th day was no ice to be seen between London Bridge and Lambeth; which sudden thaw caused great floods and high waters, that bare down bridges and houses, and drowned many people, especially in Yorkshire.'  A protracted frost necessarily deranges the lower class of employments in such a city as London, and throws many poor persons into destitution. Just as sure as this is the fact, so sure is it that a vast horde of the class who systematically avoid regular work, preferring to live by their wits, simulate the characteristic appearances of distressed labourers, and try to excite the charity of the better class of citizens. Investing themselves in aprons, clutching an old spade, and hoisting as their signal of distress a turnip on the top of a pole or rake, they will wend their way through the west-end streets, proclaiming themselves in sepulchral tones as Frozen-out Gardeners, or simply calling, 'Hall frozen hout!' or chanting 'We've got no work to do The faces of the corps are duly dolorous; but one can nevertheless observe a sharp eye kept on the doors and windows they are passing, in order that if possible they may arrest some female gaze on which to practise their spell of pity. It is alleged on good grounds that the generality of these victims of the frost are impostors, and that their daily gatherings will often amount to double a skilled workman's wages. Nor do they usually discontinue the trade till long after the return of milder airs has liquidated even real claims upon the public sympathy. When, like a sullen exile driven forth, Southward, December drags his icy chain, He graves fair pictures of drags native North On the crisp window-pane. So some pale captive blurs, with lips unshorn, The latticed glass, and shapes rude outlines there, With listless finger and a look forlorn, Cheating his dull despair. The fairy fragments of some Arctic scene I see to-night; blank wastes of polar snow, Ice-laden boughs, and feathery pines that lean Over ravines below. Black frozen lakes, and icy peaks blown bare, Break the white surface of the crusted pane, And spear-like leaves, long ferns, and blossoms fair Linked in silvery chain. Draw me, I pray thee, by this slender thread; Fancy, thou sorceress, bending vision-wrought O'er that dim well perpetually fed By the clear springs of thought! Northward I turn, and tread those dreary strands, Lakes where the wild fowl breed, the swan abides; Shores where the white fox, burrowing in the sands, Harks to the droning tides. And seas, where, drifting on a raft of ice, The she-bear rears her young; and cliffs so high, The dark-winged birds that emulate their rise Melt through the pale blue sky. There, all night long, with far diverging rays, And stalking shades, the red Auroras glow; From the keen heaven, meek suns with pallid blaze Light up the Arctic snow. Guide me, I pray, along those waves remote, That deep unstartled from its primal rest; Some errant sail, the fisher's lone light boat Borne waif-like on its breast! Lead me, I pray, where never shallop's keel Brake the dull ripples throbbing to their caves; Where the mailed glacier with his armed heel Spurs the resisting waves! Paint me, I pray, the phantom hosts that hold Celestial tourneys when the midnight calls On airy steeds, with lances bright and bold, Storming her ancient halls. Yet, while I look, the magic picture fades; Melts the bright tracery from the frosted pane; Trees, vales, and cliffs, in sparkling snows arrayed, Dissolve in silvery rain. Without, the day's pale glories sink and swell Over the black rise of you wooded height; The moon's thin crescent, like a stranded shell, Left on the shores of night. Hark how the north wind, with a hasty hand, Rattling my casement, frames his mystic rhyme. House thee, rude minstrel, chanting through the land, Runes of the olden times. INFERNAL MACHINESThe 14th of January 1858 was made memorable in France by an attempt at regicide, most diabolical in its character, and yet the project of a man who appears to have been by no means devoid of virtue and even benevolence. It was, however, the third time that what the French call an Infernal Machine was used in the streets of Paris, for regicidal purposes, within the present century. The first was a Bourbonist contrivance directed against the life of the First Consul Bonaparte. This machine,' says Sir Walter Scott, in his Life of Napoleon, 'consisted of a barrel of gunpowder, placed on a cart, to which it was strongly secured, and charged with grape-shot, so disposed around the barrel as to be dispersed in every direction by the explosion. The fire was to be communicated by a slow match. It was the purpose of the conspirators, undeterred by the indiscriminate slaughter which such a discharge must occasion, to place the machine in the street, through which the First Consul must go to the opera; having contrived that it should explode exactly as his carriage should pass the spot.' Never, during all his eventful life, had Napoleon a narrower escape than on this occasion, on the 14th of December 1800. St. Regent applied the match, and an awful explosion took place. Several houses were damaged, twenty persons were killed on the spot, and fifty-three wounded, including St. Regent himself. Napoleon's carriage, however, had just got beyond the reach of harm. This atrocity led to the execution of St. Regent, Carbon, and other conspirators. Fieschi's attempt at regicide in 1835 was more elaborate and scientific; there was something of the artillery officer in his mode of proceeding, although he was in truth nothing but a scamp. Fieschi hired a front room of a house in Paris, in a street through which royal cortéges were sometimes in the habit of passing; he proceeded to construct a weapon to be fired off through the open window, on some occasion when the king was expected to pass that way. He made a strong frame, supported by four legs. He obtained twenty-five musket barrels, which he ranged with their butt ends raised a little higher than the muzzles, in order that he might fire downwards, from a first floor window into the street. The barrels were not ranged quite parallel, but were spread out slightly like a fan; the muzzles were also not all at the same height; so that by this combined plan he obtained a sweep of fire, both in height and breadth, more extensive than he would otherwise have obtained. Every year during Louis Philippe's reign there were certain days of rejoicing in July, in commemoration of the circumstances which placed him on the throne. On the 28th, the second day of the festival in 1835, a royal cortége was proceeding along this particular street, the Boulevard du Temple. Fieschi adjusted his machine, heavily loaded with ball (four to each barrel), and connected the touch-holes of all his twenty-five barrels with a train of gunpowder. He had a blind at his window, to screen his operations from view. Just as the cortége arrived, he raised his blind and fired, when a terrific scene was presented. Marshal Mortier, General de Verigny, the aide-de-camp of Marshal Maison, a colonel, several grenadiers of the Guard, and several bystanders, were killed, while the wounded raised the number of sufferers to nearly forty. In this, as in many similar instances, the person aimed at escaped. One ball grazed the king's arm, and another lodged in his horse's neck: but he and his sons were in other respects unhurt. Fieschi was executed; and his name obtained for some years that kind of notoriety which Madame Tussaud could give it. We now come to the attempt of Orsini and his companions. A Birmingham manufacturer was commissioned to make six missiles according to a particular model. The missile was of oval shape, and had twenty-five nipples near one end, with percussion caps to fit them. The greatest thickness and weight of metal were at the nipple end, to ensure that it should come foremost to the ground. The inside was to be filled with detonating composition, such as fulminate of mercury; a concussion would explode the caps on the nipples, and communicate the explosion to the fulminate, which would burst the iron shell into innumerable fragments. A Frenchman residing in London bought alcohol, mercury, and nitric acid; made a detonating compound from these materials, and filled the shells with it. Then ensued a very complicated series of manoeuvres to get the conspirators and the shells to Paris, without exciting the suspicion of the authorities. On the evening of the 14th of January 1858, the Emperor and Empress were to go to the opera; and Orsini and his confederates prepared for the occasion. At night, while the imperial carriage was passing, three explosions were heard. Several soldiers were wounded; the Emperor's hat was perforated; General Roquet was slightly wounded in the neck; two footmen were wounded while standing behind the Emperor's carriage; one horse was killed; the carriage was severely shattered; and the explosion extinguished most of the gas-lights near at hand. The Emperor, cool in the midst of danger, proceeded to the opera as if nothing had happened. When the police had sought out the cause of this atrocity, it was ascertained that Orsini, Pierri, Radio, and Gomez were all on the spot; three of the shell-grenades had been thrown by hand, and two more were found on Orsini and Pierri. The fragments of the three shells had inflicted the frightful number of more than five hundred wounds-Orsini himself had been struck by one of the pieces. Rudio and Gomez were condemned to the galleys; Orsini and Pierri were executed. Most readers will remember the exiting political events that followed this affair in England and France, nearly plunging the two countries into war. THE FEAST OF THE ASSFormerly, the Feast of the Ass was celebrated on this day, in commemoration of the 'Flight into Egypt.' Theatrical representations of Scripture history were originally intended to impress religious truths upon the minds of an illiterate people, at a period when books were not, and few could read. But the advantages resulting from this mode of instruction were counterbalanced by the numerous ridiculous ceremonies which they originated. Of these probably none exceeded in grossness of absurdity the Festival of the Ass, as annually performed on the 14th of January. The escape of the Holy Family into Egypt was represented by a beautiful girl holding a child at her breast, and seated on an ass, splendidly decorated with trappings of gold-embroidered cloth. After having been led in solemn procession through the streets of the city in which the celebration was held, the ass, with its burden, was taken into the principal church, and placed near the high altar, while the various religious services were performed. In place, however, of the usual responses, the people on this occasion imitated the braying of an ass; and, at the conclusion of the service, the priest, instead of the usual benediction, brayed three times, and was answered by a general hee-hawing from the voices of the whole congregation. A hymn, as ridiculous as the ceremony, was sung by a double choir, the people joining in the chorus, and imitating the braying of an ass. Ducange has preserved this burlesque composition, a curious medley of French and mediæval Latin, which may be translated thus: From the country of the East, Came this strong and handsome beast: This able ass, beyond compare, Heavy loads and packs to bear. Now, seignior ass, a noble bray, Thy beauteous mouth at large display; Abundant food our hay-lofts yield, And oats abundant load the field. Hee-haw! He-haw! He-haw! True it is, his pace is slow, Till he feels the quickening blow; Till he feel the urging goad, On his hinder part bestowed. Now, seignior ass, &c. He was born on Shechem's hill; In Reuben's vales he fed his fill; He drank of Jordan's sacred stream, And gambolled in Bethlehem. Now, seignior ass, &c. See that broad majestic ear! Born he is the yoke to wear: All his fellows he surpasses! He's the very lord of asses! Now, seignior ass, &c. In leaping he excels the fawn, The deer, the colts upon the lawn; Less swift the dromedaries ran, Boasted of in Midian. Now, seignior ass, &c. Gold from Araby the blest, Seba myrrh, of myrrh the best, To the church this ass did bring; We his sturdy labours sing. Now, seignior ass, &c. While he draws the loaded wain, Or many a pack, he don't complain. With his jaws, a noble pair, He doth craunch his homely fare. Now, seignior ass, &c.' The bearded barley and its stem, And thistles, yield his fill of them: He assists to separate, When it 's threshed, the chaff from wheat. Now, seignior ass, &c. With your belly full of grain, Bray, most honoured ass, Amen! Bray out loudly, bray again, Never mind the old Amen; Without ceasing, bray again, Amen! Amen! Amen! Amen! Hee-haw! He-haw! He-haw! The 'Festival of the Ass,' and other religious burlesques of a similar description, derive their origin from Constantinople; being instituted by the Patriarch Theophylact, with the design of weaning the people's minds from pagan ceremonies, particularly the Bacchanalian and calendary observances, by the substitution of Christian spectacles, partaking of a similar spirit of licentiousness,-a principle of accommodation to the manners and prejudices of an ignorant people, which led to a still further adoption of rites, more or less imitated from the pagans. According to the pagan mythology, an ass, by its braying, saved Vesta from brutal violence, and, in consequence, ' the coronation of the ass ' formed a part of the ceremonial feast of the chaste goddess. An elaborate sculpture, representing a kneeling ass, in the church of St. Anthony at Padua, is said to commemorate a miracle that once took place in that city. It appears that one morning, as St. Anthony was carrying the sacrament to a dying person, some profane Jews refused to kneel as the sacred vessels were borne past them. But they were soon rebuked and put to contrition and shame, by seeing a pious ass kneel devoutly in honour of the host. The Jews, converted by this miracle, caused the sculpture to be erected in the church. It takes but little to make a miracle. The following anecdote, told by the Rev John Wesley, in his Journal, would, in other hands, have made a very good one: 'An odd circumstance,' says Mr. Wesley, 'happened at Rotherham during the morning preaching. It was well only serious persons were present. An ass walked gravely in at the gate, came up to the door of the house, lifted up his head, and stood stock still, in a posture of deep attention. Might not the dumb beast reprove many, who have far less decency, and not much more understanding?' A somewhat similar asinine sensibility was differently displayed in the presence of King Henry IV of France-the ass, on this occasion, not exhibiting itself as a dumb animal. When passing through a small town, just as the King was getting tired of a long stupid speech de-livered by the mayor, an ass brayed out loudly; and Henry, with the greatest gravity and politeness of tone, said: 'Pray, gentlemen, speak one at a time, if you please.' MALLARD DAYThe 14th of January is celebrated in All Souls College, Oxford, by a great merrymaking, in commemoration of the finding of an overgrown mallard in a drain, when they were digging a foundation for the college buildings, anno 1437. The following extract from a contemporary chronicle gives an account of the incident: 'Whenas Henrye Chichele, the late renowned archbishope of Cantorberye, had minded to founden a collidge in Oxenforde, for the hele of his soule and the smiles of all those who peryshed in the warres of Fraunce, fighteing valiantlye under our most gracious Henrye the fifthe, moche was he distraughten concerning the place he myghte choose for thilke purpose. Him thinkyth some whylest how he myghte place it withouten the eastern porte of the citie, both for the pleasauntnesse of the meadowes and the clere streamys therebye runninge. Agen him thinkyth odir whylest howe he mote builden it on the northe side for the heleful ayre there coming from the fieldes. Nowe while he doubteth thereon he dremt, and behold there appereth unto him one of righte godelye personage, sayinge and adviseing as howe he myghte platen his collidge in the highe strete of the citie, nere unto the chirche of our blessed ladie the Yirgine, and in witnesse that it was sowthe, and no vain and deceitful phantasie, welled him to laye the first stane of the foundation at the corner which turncth towards the Cattys Strete, where in delvinge he myghte of a suretye finde a scliwoppinge mallarde imprisoned in the sinke or sewere, wele yfattened and almost ybosten. Sure token of the thrivaunce of his future college. ' Moche doubteth he when he awoke on the nature of this vision, whethyr he mote give hede thereto or not. Then advisyth he there with monie docters and learnyd clerkys, who all seyde howe he oughte to maken trial upon it. Then comyth he to Oxenforde, and on a daye fixed, after masse seyde, proceedeth he in solemnee wyse, with spades and pickaxes for the nonce provided, to the place afore spoken of. But long they had not digged ere they herde, as it myghte seme, within the wam of the erthe, horrid strugglinges and flutteringes, and anon violent quaakinges of the distressyd mallarde. Then Chichele lyfteth up his hondes and seyth Bonedicite, &c. &c. Nowe when they broughte him forth, behold the size of his bodie was as that of a bustarde or an ostridge. And mock wonder was thereat; for the lycke had not been scene in this londe, ne in onie odir.' We obtain no particulars of the merrymaking beyond a quaint song said to have been long sung on the occasion: 'THE MERRY OLD SONG OF THE ALL SOULS' MALLARD Griffin, bustard, turkey, capon, Let other hungry mortals gape on; And on the bones their stomach fall hard, But let All Souls' men have their MALLARD. Oh! by the blood of King Edward, Oh! by the blood of King Edward, It was a wopping, wopping MALLARD. Because he saved, if some don't fool us, The place that 's called th' head of Totes. Oh! by the blood, &c. The poets feign Jove turned a swan, But let them prove it if they can; As for our proof, 'tis not at all hard, For it was a wopping, wopping MALLARD. Oh! by the blood, &c. Therefore let us sing and dance a galliard, To the remembrance of the MALLARD: And as the MALLARD dives in pool, Let us dabble, dive, and duck in bowl. Oh! by the blood of King Edward, Oh! by the blood of King Edward, It was a wopping, wopping MALLARD. MISERRIMUSIn the north aisle of the cloister of Worcester Cathedral is a sepulchral slab, which bears only the word MISERRIMUS, expressing that a most miserable but unknown man reposes below. The most heedless visitor is arrested by this sad voice speaking, as it were, from the ground; and it is no wonder that the imaginations of poets and romancists have been awakened by it: Miserrimus! 'and neither name nor date, Prayer, text, or symbol, graven upon the stone; Nought but that word assigned to the unknown, That solitary word-to separate From all, and cast a cloud around the fate Of him who lies beneath. Most wretched one! Who chose his epitaph?-Himself alone Could thus have dared the grave to agitate, And claim among the dead this awful crown; Nor doubt that he marked also for his own, Close to these cloistral steps, a burial-place, That every foot might fall with heavier tread, Trampling upon his vileness. Stranger, pass Softly!-To save the contrite Jesus bled! There has of course been much speculation regarding the identity of Miserrimus: even a novel has been written upon the idea, containing striking events and situations, and replete with pathos. It is alleged, however, that the actual person was no hero of strikingly unhappy story, but only a 'Rev Thomas Morris, who, at the Revolution refusing to acknowledge the king's supremacy [more probably refusing to take the oaths to the new monarch], was deprived of his preferment, and depended for the remainder of his life on the benevolence of different Jacobites.' At his death, viewing merely, we suppose, the extreme indigence to which he was reduced, and the humiliating way in which he got his living, he ordered that the only inscription on his tomb should be-MISERRIMUS! Such freaks are not unexampled, and we cannot be always sure that there is a real correspondence between the inscription and the fact or instance, a Mr. Francis Cherry of Shottesbrooke, who died September 23rd, 1713, had his grave inscribed with no other words than Hic JACET PECCATORUM MAXIMUS (Here lies the Chief of Sinners), the truth being, if we are to believe his friend Hearne, that he was an upright and amiable man, of the most unexceptionable religious practice-in Hearne's own words, 'one of the most learned, modest, humble, and virtuous persons that I ever had the honour to be acquainted with.' The writer can speak on good authority of a similar epitaph which a dying person of unhappy memory desired to be put upon his coffin. The person referred to was an Irish ecclesiastic who many years ago was obliged, in consequence of a dismal lapse, to become as one lost to the world. Fully twenty-five years after his wretched fall, an old and broken down man, living in an obscure lodging at Newington, a suburb of Edinburgh, sent for one of the Scottish Episcopalclergy, for the benefit of his ministrations as to a dying person. Mr. F- saw much in this aged man to interest him; he seemed borne down with sorrow and penitence. It was tolerably evident that he shunned society, and lived under a feigned name and character. Mr. F--- became convinced that he had been a criminal, but was not able to penetrate the mystery. The miserable man at length had to give some directions about his funeral-an evidently approaching event; and he desired that the only inscription on his coffin should be 'A CONTRITE SINNER.' He was in due time deposited without any further memorial in Warriston Cemetery, near Edinburgh. |