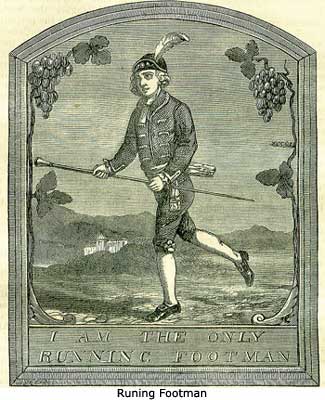

12th JanuaryBorn: George Fourth Earl of Clarendon, 1800. Died: The Emperor Maximilian I, 1519; the Duke of Alva, Lisbon, 1583; John C. Lavater, 1801, Zurich. Feast Day: St. Arcadius, martyr. St. Benedict, commonly called Bonnet, 690. St. Tygrius, priest. St. Allied, 1166. ST. BENEDICT BISCOPBiscop was a Northumbrian monk, who paid several visits to Rome, collecting relics, pictures, and books, and finally was able to found the two monasteries of Wearmouth and Jarrow. Lambarde, who seems to have been no admirer of ornamental architecture or the fine arts, thus speaks of St. Benedict Biscop: 'This man laboured to Rome five several tymes, for what other thinge I find not save only to procure pope-holye privileges, and curious ornaments for his monasteries, Jarrow and Weremouth; for first he gotte for theise houses, wherein he nourished 600 monks, great liberties; then brought he them home from Rome, painters, glasiers, free-masons, and singers, to th' end that his buildings might so shyne with workmanshipe, and his churches so sounde with melodye, that simple souls ravished therewithe should fantasie of theim nothinge but heavenly holynes. In this jolitie continued theise houses, and other by theire example embraced the like, till Hinguar and Hubba, the Danish pyrates, A.D. 870, were raised by God to abate their pride, who not only fyred and spoyled them, but also almost all the religious houses on the north-cast coast of the island.' THE DUKE OF ALVAThis great general of the Imperial army and Minister of State of Charles V, was educated both for the field and the cabinet, though he owed his promotion in the former service rather to the caprice than the perception of his sovereign, who promoted him to the first rank in the army more as a mark of favour than from any consideration of his military talents. He was undoubtedly the ablest general of his age. He was principally distinguished for his skill and prudence in choosing his positions, and for maintaining strict discipline in his troops. He often obtained, by patient stratagem, those advantages which would have been thrown away or dearly acquired by a precipitate encounter with the enemy. On the Emperor wishing to know his opinion about attacking the Turks, he advised him rather to build them a golden bridge than offer them a decisive battle. Being at Cologne, and avoiding, as he always did, an engagement with the Dutch troops, the Archbishop urged him to fight. 'The object of a general,' answered the Duke, 'is not to fight, but to conquer; he fights enough who obtains the victory.' During a career of so many years, he never lost a battle. While we admire the astute commander, we can never hear the name of Alva without horror for the cruelties of which he was guilty in his endeavours to preserve the Low Countries for Spain. During his government in Holland, he is reckoned to have put 18,000 of the citizens to death. Such were the extremities to which fanaticism could carry men generally not deficient in estimable qualities, during the great controversies which rose in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. GREAT EATERSUnder January 12, 1722-3, Thomas Hearne, the antiquary, enters in his Diary, what he had learned regarding a man who had been at Oxford not long before,-a man remarkable for a morbid appetite, leading him to devour large quantities of raw, half-putrid meat. The common story told regarding him was, that he had once at-tempted to imitate the Saviour in a forty days' Lent fast, broke down in it, and 'was taken with this unnatural way of eating.' One of the most remarkable gluttons of modern times was Nicholas Wood, of Harrison, in Kent, of whom Taylor, the Water Poet, wrote an amusing account, in which. the following feat is described: 'Two loynes of mutton and one loyne of veal were but as three sprats to him. Once, at Sir Warham St. Leger's house, he showed himself so violent of teeth and stomach, that he ate as much as would have served and sufficed thirty men, so that his belly was like to turn bankrupt and break, but that the serving-man turned him to the fire, and anointed his paunch with grease and butter, to make it stretch and hold; and afterwards, being laid in bed, he slept eight hours, and fasted all the while; which, when the knight understood, he commanded him to be laid in the stocks, and there to endure as long as he had laine bedrid with eating.' In a book published in 1823, under the title of Points of humour, having illustrations by the unapproachable George Cruikshank, there is a droll anecdote regarding an inordinate eater: When Charles Gustavus, King of Sweden, was besieging Prague, a boor of a most extraordinary visage desired admittance to hits tent; and being allowed to enter, he offered, by way of amusement, to devour a large hog in his presence. The old General Kænigsmark, who stood by the King's side, hinted to his royal master that the peasant ought to be burnt as a sorcerer. 'Sir,' said the fellow, irritated at the remark, 'if your Majesty will but make that old gentleman take off his sword and spurs, I will eat him before I begin the pig.' General Kænigsmark, who, at the head of a body of Swedes, performed wonders against the Austrians, could not stand this proposal, especially as it was accompanied by a most hideous expansion of the jaws and mouth. Without uttering a word, the veteran turned pale, and suddenly ran out of the tent; nor did he think himself safe till he arrived at his quarters.' EARLY RISING IN WINTERLord Chatham, writing to his nephew, January 12, 1754, says: 'Vitanda est improba Syren, Desidia, I desire may be affixed to the curtains of your bedchamber. If you do not rise early, you can never make any progress worth mentioning. If you do not set apart your hours of reading; if you suffer yourself or any one else to break in upon them, your days will slip through your hands unprofitably and frivolously, unpraised by all you wish to please, and really unenjoyed by yourself.' It must, nevertheless, be owned that to rise early in cold weather, and in the gloomy dusk of a January morning, requires no small exertion of virtuous resolution, and is by no means the least of life's trials. Leigh Hunt has described the trying character of the crisis in his Indicator: 'On opening my eyes, the first thing that meets them is my own breath rolling forth, as if in the open air, like smoke out of a cottage-chimney. Think of this symptom. Then I turn my eyes sideways and see the window all frozen over. Think of that. Then the servant comes in. 'It is very cold this morning, is it not?'-'Very cold, sir.'-'Very cold indeed, isn't it ?' --'Very cold indeed, sir.'-'More than usually so, isn't it, even for this weather?' (Here the servant's wit and good nature are put to a considerable test, and the inquirer lies on thorns for the answer.) 'Why, sir, .. I think it is.' (Good creature! There is not a better or more truth-telling servant going.) 'I must rise, how-ever. Get me some warm water.'-Here comes a fine interval between the departure of the servant and the arrival of the hot water; during which, of course, it is of 'no use' to get up. The hot water comes. 'Is it quite hot?'-'Yes, sir.'-'Perhaps too hot for shaving: I must wait a little ?'-'No, sir; it will just do.' (There is an over-nice propriety sometimes, an officious zeal of virtue, a little troublesome.) 'Oh-the shirt-you must air my clean shirt:-linen gets very damp this weather.'-'Yes, sir.' Here another delicious five minutes. A knock at the door. 'Oh, the shirt-very well. My stockings -I think the stockings had better be aired too.' -'Very well, sir.'-Here another interval. At length everything is ready, except myself. I now cannot help thinking a good deal-who can?-upon the unnecessary and villanous custom of shaving; it is a thing so unmanly (here I nestle closer)-so effeminate, (here I recoil from an unlucky step into the colder part of the bed.)-No wonder, that the queen of France took part with the rebels against that degenerate king, her husband, who first affronted her smooth visage with a face like her own. The Emperor Julian never showed the luxuriancy of his genius to better advantage than in reviving the flowing beard. Look at Cardinal Bembo's picture-at Michael Angelo's-at Titian's-at Shakspeare's -at Fletcher's-at Spenser's-at Chaucer's-at Alfred's-at Plato's. I could name a great man for every tick of my watch. Look at the Turks, a grave and otiose people-Think of Haroun Al Raschid and Bed-ridden Hassan- Think of Wortley Montague, the worthy son of his mother, a man above the prejudice of his time-Look at the Persian gentlemen, whom one is ashamed of meeting about the suburbs, their dress and appearance are so much fluor than our own-Lastly, think of the razor itself - how totally opposed to every sensation of bed-how cold, how edgy, how hard! how utterly different from anything like the warm and circling amplitude which Sweetly recommends itself Unto our gentle senses. Add to this, benumbed fingers, which may help you to cut yourself, a quivering body, a frozen towel, and an ewer full of ice; and he that says there is nothing oppose in all this, only shews, at any rate, that he has no merit in opposing it.' RUNNING FOOTMANDown to the time of our grandfathers, while there was less conveniency in the world than now, there was much more state. The nobility lived in a very dignified way, and amongst the particulars of their grandeur was the custom of keeping running footmen. All great people deemed it a necessary part of their travelling equipage, that one or more men should run in front of the carriage, not for any useful purpose, unless it might be in some instances to assist in lifting the carriage out of ruts, or helping it through rivers, but principally and professedly as a mark of the consequence of the traveller. Heads being generally bad, coach travelling was not rapid in those days; seldom above five miles an hour. The strain required to keep up with his master's coach was accordingly not very severe on one of these officials; at least, it was not so till towards the end of the eighteenth century, when, as a consequence of the acceleration of travelling, the custom began to be given up. Nevertheless, the running footman required to be a healthy and agile man, and both in his dress and his diet a regard was had to the long and comparatively rapid journeys which he had to perform. A light black cap, a jockey coat, white Linen trousers, or a mere linen shirt coming to the knees, with a pole six or seven feet long, constituted his outfit. On the top of the pole was a hollow ball, in which he kept a hard-boiled egg, or a little white wine, to serve as a refreshment in his journey; and this ball-topped pole seems to be the original of the long silver-headed cane which is still borne by footmen at the backs of the carriages of the nobility. A clever runner in his best clays would undertake to do as much as seven miles an hour, when necessary, and go three-score miles a day; but, of course, it was not possible for any man to last long who tasked himself in this manner. The custom of keeping running footmen survived to such recent times that Sir Walter Scott remembered seeing the state-coach of John Earl of Hopetoun attended by one of the fraternity, clothed in white, and bearing a staff.' It is believed that the Duke of Queensberry who died in 1810, kept up the practice longer than any other of the London grandees: and Mr. Thorns tells an amusing anecdote of a man who came to be hired for the duty by that ancient but far from venerable peer. His grace was in the habit of trying their paces by seeing how they could run up and down Piccadilly, he watching and timing them from his balcony. They put on a livery before the trial. On one occasion, a candidate presented himself, dressed, and ran. At the conclusion of his performance he stood before the balcony. 'You will do very well for me,' said the duke. 'And your livery will do very well for me,' replied the man, and gave the duke a last proof of his ability as a runner by then running away with it.  Running footmen were employed by the Austrian nobility down to the close of the last century. Mrs. St George, describing her visit to Vienna at that time, expresses her dislike of the custom, as cruel and unnecessary. 'These unhappy people,' she says, 'always precede the carriage of their masters in town, and sometimes even to the suburbs. They seldom live above three or four years, and generally die of consumption. Fatigue and disease are painted in their pallid and drawn features; but, like victims, they are crowned with flowers, and adorned with tinsel.' The dress of the official abroad seems to have been of a very gaudy character. A contributor to the Notes and Queries describes in vivid terms the appearance of the three footmen who preceded the King of Saxony's carriage, on a road near Dresden, on a hot July day in 1845: First, in the centre of the dusty chaussee, about thirty yards ahead of the foremost horses' heads, came a tall, thin, white-haired old man; he looked six feet high, about seventy years of age, but as lithe as a deer; his legs and body were clothed in drawers or tights of white linen; his jacket was like a jockey's, the colours blue and yellow, with lace and fringes on the facings; on his head a sort of barret cap, slashed and ornamented with lace and embroidery, and decorated in front with two curling heron's plumes; round his waist a deep belt of leather with silk and lace fringes, tassels, and quaint embroidery, which seemed to serve as a sort of pouch to the wearer. In his right hand he held, grasped by the middle, a staff about two feet long, carved and pointed with a silver head, and something like bells or metal drops hung round it, that gingled as he ran. Behind him, one on each side of the road, dressed and accoutred in the same style, came his two sons, handsome, tall young fellows of from twenty to twenty-five years of age; and so the king passed on.' In our country, the running footman was occasionally employed upon simple errands when unusual dispatch was required. In the neighbourhood of various great houses in Scotland, the country people still tell stories illustrative of the singular speed which these men attained. For example: the Earl of Home, residing at Hume Castle in Berwickshire, had occasion to send his foot-man to Edinburgh one evening on important business. Descending to the hall in the morning, he found the man asleep on a bench, and, thinking he had neglected his duty, prepared to chastise him, but found, to his surprise, that the man had been to Edinburgh (thirty-five miles) and back, with his business sped, since the past evening. As another instance: the Duke of Landerdale, in the reign of Charles II, being to give a large dinner-party at his castle of Thirlstane, near Lander, it was discovered, at the laying of the cloth, that songe additional plate would be required from the Duke's other seat of Lethington, near Haddington, fully fifteen miles distant across the Lammirmuir hills. The running footman instantly darted off, and was back with the required articles in time for dinner! The great boast of the running footman was that, on a long journey, he could beat a horse. 'A traditional anecdote is related of one of these fleet messengers (rather half-witted), who was sent from Glasgow to Edinburgh for two doctors to come to see his sick master. He was interrupted on the road with an inquiry how his master was now. 'He's no dead yet,' was the reply; 'but he'll soon be, for I'm fast on the way for to a Edinburgh doctors to conic and visit him.' Langham, an Irishman, who served Henry Lord Berkeley as running footman in Elizabeth's time, on one occasion, this noble's wife being sick: 'carried a letter from Callowdon to old Dr Fryer, a physician dwelling in Little Britain in London, and returned with a glass bottle in his hand, compounded by the doctor, for the recovery of her health, a journey of 148 miles performed by him in less than forty-two hours, notwithstanding his stay of one night at the physician's and apothecary's houses, which no one horse could have so well and safely per-formed; for which the Lady shall after give him a new suit of clothes.'-Berkeley Manuscripts, 4 to, 1821, p. 204. The memory of this singular custom is kept alive in the ordinary name for a manservant--a footman. In Charles Street, Berkeley Square, London, there is a particular memorial of it in the sign of a public-house, called The Banning Footman, much used by the servants of the neighbouring gentry. Here is represented a tall, agile man in gay attire, and with a stick having a metal ball at top; he is engaged in running. |