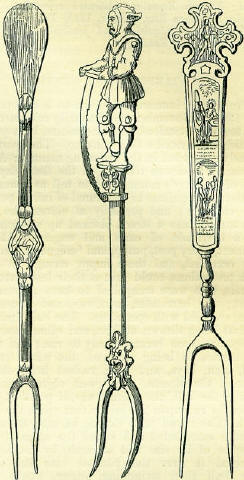

12th NovemberBorn: Richard Baxter, eminent nonconformist divine, 1615, Bowdon, Shropshire; Admiral Edward Vernon, naval commander, 1684, Westminster; Amelia Opie, novelist, 1769, Norwich. Died: Pope Boniface III, 606; Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, 1555; Peter Martyr, distinguished reformer, 1562, Zurich; Sir John Hawkins, eminent navigator, 1595; William Hayley, biographer of Cowper, 1820, Felpham; John M'Diarmid, miscellaneous writer, 1852; Charles Kemble, eminent actor, 1854. Feast Day: St. Nilus, anchoret, father of the church, and confessor, 5th century. St. Martin, pope and martyr, 655. St. Livin, bishop and martyr, 7th century. St. Lebwin, patron of Daventer, confessor, end of 8th century. THE ORDER OF FOOLSOn 12th November 1381, the above association is said to have been founded by Adolphus, Count of Cleves, under the title of 'D'Order van't gaken Gesellschap.' Though bearing a designation savouring so strongly of absurdity and contempt, the members of which this order was composed were noblemen and gentlemen of the highest rank and renown, who thus formed themselves into a body for humane and charitable purposes. We should be doing these gallant knights a grievous injustice were we to connect them with the Feast of Fools, and similar absurdities of medieval times. They were, in fact, not greatly dissimilar to the 'Odd Fellows,' 'Foresters,' and similar associations of the present day, which include within their sphere of operations benevolent and useful as much as convivial and social objects. The insignia borne by the knights of this order consisted of the figure of a fool or jester, embroidered on the left side of their mantles, and depicted dressed in a red and silver vest, with a cap and bells on his head, yellow stockings, a cup filled with fruits in his right hand, and in his left a gold key, as symbolical of the affection which ought to subsist between the members of the society. A yearly meeting of the brotherhood of Fools took place at Cleves on the first Sunday after Michaelmas-day, when a grand court was held, extending over seven days, and all matters relating to the welfare and future conduct of the order were revolved and discussed. Each member had some special character assigned to him, which he was obliged to support, and the most cordial equality everywhere prevailed, all distinctions of rank being laid aside. The Order of Fools appears to have existed down to the beginning of the sixteenth century, but the objects for which it was originally founded seem, as in the case of the Knights Templars, to have gradually been lost sight of, and ultimately became almost wholly forgotten. The latest allusion to it occurs in some verses prefixed to a German translation of Sebastian Brand's celebrated Navis Stultifera, or Ship of Fools, published at Strasburg in 1520. Akin to the Order of Fools was the 'Respublica Binepsis,' which was founded by some Polish noblemen about the middle of the fourteenth century, and derived its name from the estate of its principal originator. Its constitution was modelled after that of Poland, and, like that kingdom, it too had its sovereign, its council, its chamberlain, its master of the chase, and various other offices. Any member who made himself conspicuous by some absurd or singular propensity, received a recognition of this quality from his fellows by having assigned to him a corresponding appointment in the society. Thus the dignity of master of the hunt was conferred on some individual who carried to an absurd extreme his passion for the chase, whilst another person given to gasconading and boasting of his valorous exploits, was elevated to the post of field-marshal. No member could decline acceptance of any of these functions, unless he wished to make himself an object of still greater ridicule and animadversion. At the same time, all persons given to lampooning or personal satire, were excluded from admission to the association. The order rapidly increased in numbers from the period of its formation, and at one time comprised nearly all the individuals attached to the Polish court. Like the German association, its objects were the promotion of charity and good-feeling, and the repression of immoral and absurd habits and practices. PLAYGOING-HOURS IN THE OLDEN TIMEBy a police regulation of the city of Paris, dated 12th November 1609, it is ordered that the players at the theatres of the Hotel de Bourgogne and the Marais shall open their doors at one o'clock in the afternoon, and at two o'clock precisely shall commence the performance, whether there are sufficient spectators or not, so that the play may be over before half-past four. This ordinance, it was enacted, should be in force from the Feast of St. Martin to the 15th of the ensuing month of February. Such hours for visiting the playhouse seem peculiarly strange at the present day, when the doors of theatres are seldom opened before half-past six in the evening, or shut before mid-night. But our ancestors both closed and opened the day much earlier than we do now, and observed much more punctually the old recipe for health and strength, 'to rise with the lark and lie down with the lamb: The same early hours for theatrical representations that seem thus to have prevailed in Paris were, during the seventeenth century, no less common in England, where, as we learn from the first playbill issued from the Drury Lane Theatre in 1663, the hour for the commencement of the representation was three o'clock in the afternoon. The badness of the streets, and the danger of traversing them in dark nights from the defective mode of lighting, combined with the absence of an efficient police and the dangers from robbery and violence, all had their influence in rendering it very undesirable to protract public amusements beyond nightfall in those times. ANCIENT FORKS From a passage in that curious work, Coryate's Crudities, it has been imagined that its author, the strange traveller of that name, was the first to introduce the use of the fork into England, in the beginning of the seventeenth century. He says that he observed its use in Italy only 'because the Italian cannot by any means endure to have his dish touched with fingers, seeing all men's fingers are not alike clean.' These 'little forks' were usually made of iron or steel, but occasionally also of silver. Coryate says he 'thought good to imitate the Italian fashion by this forked cutting of meat,' and that hence a humorous English friend, 'in his merry humour, doubted not to call me furcifer, only for using a fork at feeding.' This passage is often quoted as fixing the earliest date of the use of forks; but they were, in reality, used by our Anglo-Saxon forefathers, and throughout the middle ages. In 1834, some labourers found, when cutting a deep drain at Sevington, North Wilts, a deposit of seventy Saxon pennies, of sovereigns ranging from Coenwulf, king of Mercia (796 A.D.), to Ethelstan (878-890 A.D.); they had been packed in a box of which there were some decayed remains, and which also held some articles of personal ornament, a spoon, and the fork, which is first in the group here engraved. The fabric and ornamentation of this fork and spoon would, to the practised eye, be quite sufficient evidence of the approximate era of their manufacture, but their juxtaposition with the coins confirms it. In Akerman's Pagan Saxondom, another example of a fork, from a Saxon tumulus, is given: it has a bone-handle, like those still manufactured for common use. It must not, however, be imagined that they were frequently used; indeed, through-out the middle ages, they seemed to have been kept as articles of luxury, to be used only by the great and noble in eating fruits and preserves onstate occasions. A German fork, believed to be a work of the close of the sixteenth century, is the second of our examples. It is surmounted by the figure of a fool or jester, who holds a saw. This figure is jointed like a child's doll, and tumbles about as the fork is used, while the saw slips up and down the handle. It proves that the fork was treated merely as a luxurious toy. Indeed, as late as 1652, Heylin, in his Cosmography, treats them as a rarity: 'the use of silver forks, which is by sonic of our spruce gallants taken up of late; are the words he uses. A fork of this period is the third of our selected examples; it is entirely of silver, the handle elaborately engraved with subjects from the New Testament. It is one of a series so decorated, the whole of our engraved examples being at present in the collection of Lord Londesborough. In conclusion, we may observe that the use of the fork became general by the close of the seventeenth century. |