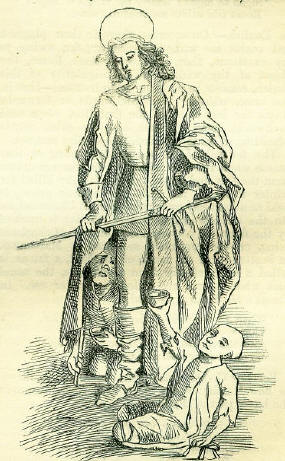

11th NovemberBorn: John Albert Fabricius, scholar and editor, 1668, Leipsic; Firmin Abauzit, celebrated man of learning, 1679, Uzès, in Languedoc; Earl of Bridgewater, founder of the Bridgewater Treatise Bequest, 1758; Marie Francois Xavier Bichat, eminent French anatomist, 1771, Thoirette; Dr. John Abercrombie, physician and author, 1781, Aberdeen. Died: Canute the Dane, king of England, 1035, Shaftesbury; Thomas, Lord Fairfax, Parliamentary general, 1671; Jean Sylvain Bailly, eminent astronomer, guillotined at Paris, 1793; Joshua Brookes, eccentric clergyman, 1821, Manchester. Feast Day: St. Mennas, martyr, about 304. St. Martin, bishop of Tours, confessor, 397. MARTINMAS St. Martin, the son of a Roman military tribune, was born at Sabaria, in Hungary, about 316. From his earliest infancy, he was remarkable for mildness of disposition; yet he was obliged to become a soldier, a profession most uncongenial to his natural character. After several years' service, he retired into solitude, from whence he was withdrawn, by being elected bishop of Tours, in the year 374. The zeal and piety he displayed in this office were most exemplary. He converted the whole of his diocese to Christianity, overthrowing the ancient pagan temples, and erecting churches in their stead. From the great success of his pious endeavours, Martin has been styled the Apostle of the Gauls; and, being the first confessor to whom the Latin Church offered public prayers, he is distinguished as the father of that church. In remembrance of his original profession, he is also frequently denominated the Soldier Saint. The principal legend, connected with St. Martin, forms the subject of our illustration, which represents the saint, when a soldier, dividing his cloak with a poor naked beggar, whom he found perishing with cold at the gate of Amiens. This cloak, being most miraculously preserved, long formed one of the holiest and most valued relics of France; when war was declared, it was carried before the French monarchs, as a sacred banner, and never failed to assure a certain victory. The oratory in which this cloak or cape-in French, chape-was preserved, acquired, in consequence, the name of chapelle, the person intrusted with its care being termed chapelain: and thus, according to Collin de Plancy, our English words chapel and chaplain are derived. The canons of St. Martin of Tours and St. Gratian had a lawsuit, for sixty years, about a sleeve of this cloak, each claiming it as their property. The Count Larochefoucalt, at last, put an end to the proceedings, by sacrilegiously committing the contested relic to the flames. Another legend of St. Martin is connected with one of those literary curiosities termed a palindrome. Martin, having occasion to visit Rome, set out to perform the journey thither on foot. Satan, meeting him on the way, taunted the holy man for not using a conveyance more suitable to a bishop. In an instant the saint changed the Old Serpent into a mule, and jumping on its back, trotted comfortably along. Whenever the transformed demon slackened pace, Martin, by making the sign of the cross, urged it to full speed. At last, Satan utterly defeated, exclaimed: Signa, te Signa,: temere me tangis et angis: Roma tibi subito motibus ibit amor. In English- Cross, cross thyself: thou plaguest and vexest me without necessity; for, owing to my exertions, thou wilt soon reach Rome, the object of thy wishes. The singularity of this distich, consists in its being palindromical-that is, the same, whether read backwards or forwards. Angis, the last word of the first line, when read backwards, forming signet, and the other words admitting of being reversed, in a similar manner. The festival of St. Martin, happening at that season when the new wines of the year are drawn from the lees and tasted, when cattle are killed for winter food, and fat geese are in their prime, is held as a feast-day over most parts of Christendom. On the ancient clog almanacs, the day is marked by the figure of a goose; our bird of Michaelmas being, on the continent, sacrificed at Martinmas. In Scotland and the north of England, a fat ox is called a mart, clearly from Martinmas, the usual time when beeves are killed for winter use. In 'Tusser's Husbandry, we read: When Easter comes, who knows not then, That veal and bacon is the man? And Martilmass beef doth bear good tack, When country folic do dainties lack. Barnaby Googe's translation of Neogeorgus, shews us how Martinmas was kept in Germany, towards the latter part of the fifteenth century To belly chear, yet once again, Doth Martin more incline, Whom all the people worshippeth With roasted geese and wine. Both all the day long, and the night, Now each man open makes His vessels all, and of the must, Oft times, the last he takes, Which holy Martin afterwards Alloweth to be wine, Therefore they him, unto the skies, Extol with praise divine. A genial saint, like Martin, might naturally be expected to become popular in England; and there are no less than seven churches in London and Westminster, alone, dedicated to him. There is certainly more than a resemblance between the Vinalia of the Romans, and the Martinalia of the medieval period. Indeed, an old ecclesiastical calendar, quoted by Brand, expressly states under 11th November: 'The Vinalia, a feast of the ancients, removed to this day. Bacchus in the figure of Martin.' And thus, probably, it happened, that the beggars were taken from St. Martin, and placed under the protection of St. Giles; while the former became the patron saint of publicans, tavern-keepers, and other 'dispensers of good eating and drinking. In the hall of the Vintners' Company of London, paintings and statues of St. Martin and Bacchus reign amicably together side by side. On the inauguration, as lord mayor, of Sir Samuel Dashwood, an honoured vintner, in 1702, the company had a grand processional pageant, the most conspicuous figure in which was their patron saint, Martin, arrayed, cap-à-pie, in a magnificent suit of polished armour; wearing a costly scarlet cloak, and mounted on a richly plumed and caparisoned white charger: two esquires, in rich liveries, walking at each side. Twenty satyrs danced before him, beating tambours, and preceded by ten halberdiers, with rural music. Ten Roman lictors, wearing silver helmets, and carrying axes and fasces, gave an air of classical dignity to the procession, and, with the satyrs, sustained the bacchanalian idea of the affair. A multitude of beggars, 'howling most lamentably,' followed the warlike saint, till the procession stopped in St. Paul's Churchyard. Then Martin, or his representative at least, drawing his sword., cut his rich scarlet cloak in many pieces, which he distributed among the beggars. This ceremony being duly and gravely performed, the lamentable howlings ceased, and the procession resumed its course to Guildhall, where Queen Anne graciously condescended to dine with the new lord mayor. A FATHER AND SON: SINGULAR SPECIMEN OF A MANCHESTER CLERGYMANOn 11th November 1821, died the Rev. Joshua Brookes, M.A., chaplain of the Collegiate Church, Manchester. He was of humble parentage, being the son of a shoemaker or cobbler, of Cheadle Hulme, near Stockport, and he was baptized, May 19th, 1754, at Stockport. His father, Thomas Brookes, was a cripple, of uncouth mien, eccentric manners, and great violence of temper, peculiarities which gained him the sobriquet of 'Pontius Pilate.' Many stories are told of his rude manners and impetuous disposition. He removed to Manchester while Joshua was yet a child, and, in his later years, occupied a house in a passage in Long Millgate, opposite the house of Mr. Lawson, then high-master of the Manchester Grammar School. At that school Joshua received his education, and, being a boy of quick parts, was much noticed by the Rev. Thomas Aynscough, one of the Fellows of the Collegiate Church, by whose assistance, and that of some of the wealthier residents of Manchester, his father was enabled to send him to Oxford, where he was entered at Brasenose College. The father went round personally to the houses of various rich inhabitants, to solicit pecuniary aid to send his son to college. Joshua took his degree of M.A. in 1771. In 1789, he was nominated by the warden and fellows of Manchester to the perpetual curacy of the chapelry of Chorlton-cum-Hardy, which he resigned in December 1790, on being appointed to a chaplaincy in the Manchester Collegiate Church, which he held till his death. During his chaplaincy of thirty-one years, he is supposed to have baptized, married, and buried more persons than any other clergyman in the kingdom. He inherited much of his father's mental constitution, especially his rough manners and extreme irascibility; but the influence of education, and a sense of what his position demanded, tended somewhat to temper his eccentricities. It is curious to mark the reflection of the illiterate father's temperament and disposition in the educated son. The father was fond of angling, and having once obtained permission to fish in the pond of Strangeway's Hall, he had an empty hogshead placed in the field, near the brink of the pond, and in this cask-a sort of vulgar Diogenes in his tub-he frequently spent whole nights in his favourite pursuit. In his later years, while sitting at his door, as was his custom, his strange appearance and figure, with a red night-cap on his head, attracted the notice of a market-woman, who, in passing, made some rude remark. Eager for revenge, and yet unable to follow her by reason of his lameness, old Brookes despatched his servant for a sedan-chair, wherein he was conveyed to the market-place; and, having singled out the object of his indignation, he belaboured her with his crutch with such fury, that she had to be rescued by a constable. He was of intemperate habits and extreme coarseness in speech, and was always getting involved in disputes and scrapes. Joshua, to his honour, always treated the old man with respect and. forbearance; and, after getting the chaplaincy, he maintained his father for many years till the latter's death. Such was the father. A few traits of the son will complete this strange picture of a pair of Manchester originals in the last century. Young Brookes was at one time an assistant-master at the Grammar School, where he made himself very unpopular with the boys, especially the senior classes, being constantly involved in warfare with them, physical and literary. Sometimes he would singly defy the whole school, and be forcibly ejected from the school-room, fighting with hand and foot against his numerous assailants, and hurling reproaches at them as 'blockheads.' On one occasion, the arrival on the spot of the head-master alone saved him from being pitched over the school-yard a rap et-wall, into the river Irk, many feet below. The upper-scholars not only ridiculed him in lampoons, but fathered verses upon him, as that celebrated wit, Bishop Mansel, did upon old Viner. He was sadly vexed by a mischievous rascal writing on his door: 'Odi profanum Bruks' [the Lancashire pronunciation of his name] 'et arceo.' Nor was he less annoyed by a satirical effusion occasioned by his inviting a friend to dine with him, and entertaining him only with a black-pudding. The lampoon in question commenced with 0' Jetty, you dog! Your house, we well know, Is head-quarters of prog. 'Jotty Bruks,' as he was usually called, may be regarded as a perpetual cracker, always ready to go off when touched or jostled in the slightest degree. He was no respecter of persons, but warred equally and indifferently with the passing chimney-sweep, the huxtress, the mother who came too late to be churched, and with his superiors, the warden and fellows. The last-mentioned parties, on one occasion, for some trivial misbehaviour, expelled him from the chapter-house, until he should make an apology. This he sturdily refused to do; but would put on his surplice in an adjoining chapel, and then, standing close outside the chapter-house door, in the south aisle of the choir, would exclaim to those who were passing on to attend divine service: 'They won't let me in. They say I can't behave myself.' At another time, he was seen, in the middle of the service, to box the ears of a chorister-boy, for coming late. Sometimes, while officiating, he would leave the choir during the musical portion of the service, go clown to the side-aisles, and chat with any lounger till the time came for his clerical functions being required in person. Once, when surprise was expressed at this unseemly procedure, he only replied: 'Oh! I frequently come out while they're singing Ta Daum.' Talking in this strain to a very aged gentleman, and often making use of the expression, 'We old men,' Mr. Johnson (in the dialect then almost universal in Manchester) turned upon him with the question: 'Why, how owd art to?' 'I'm sixty-foive,' says Jotty. 'Sixty-foive!' rejoined his aged interlocutor; 'why t 'as a lad; here's a penny for thee. Goo, buy thysel' a penny-poye [pie].' So Jetty returned to the reading-desk, to read the morning lesson, a penny richer. A child was once brought to him to be christened, whose parents desired to give it the name of Bonaparte. This designation he not only refused to bestow, but entered his refusal to do so in the register of baptisms. In the matter of marriages his conduct was peremptory and arbitrary. He so frightened a young wife, a parishioner of his, who had been married at Eccles, by telling her of consequent danger to the rights of her children, that, to make all right and sure, she was remarried by Joshua himself at the Collegiate Church. Once, when marrying a number of couples, it was found, on joining hands, that there was one woman without any bridegroom. In this dilemma, instead of declining to marry this luckless bride, Joshua required one of the men present to act as bride-groom both to her and his own partner. The lady interested, objecting to so summary a mode of getting over the difficulty, Joshua replied: ' can't stand talking to thee; prayers' [that is, the daily morning service] 'will be in directly, thou must go and find him after.' After the ceremony, the defaulter was found drunk in the 'Ring of Bells' public-house, adjoining the church. The church-yard was surrounded by a low parapet-wall, with a sharp-ridged coping, to walk along which required nice balancing of the body, and was one of the favourite ' craddies' [feats] of the neighbouring boys. The practice greatly annoyed Joshua; and one day, whilst reading the burial-service at the grave-side, his eye caught a chimney-sweep walking on the wall. This caused the eccentric chaplain, by abruptly giving an order to the beadle, to make the following interpolation in the solemn words of the funeral-service: 'And I heard a voice from heaven, saying'-- 'Knock that black rascal off the wall!' This contretemps was made the subject of a caricature by a well-known character of the day, 'Jack Batty;' who, on a prosecution for libel being instituted, left Manchester. After a long absence he returned, and on his entreating Joshua to pardon him, he was readily forgiven. Another freak of this queer parson was to leave a funeral in which he was officiating, cross the churchyard to the adjacent Half Street, and enter a confectioner's shop, kept by a widow, named Clowes, where he demanded a supply of horehound-lozenges for his throat. Having obtained these, which were never refused, though he never paid for them, he would composedly return to the grave, and resume the interrupted service. In his verbal encounters, he sometimes met with his match. One day, 'Jemmy Watson,' better known by his sobriquet of 'Doctor,' having provoked Joshua by a pun at his expense, the chaplain exclaimed: 'Thou 'rt a blackguard, Jemmy!' The Doctor retorted: 'If 'I be not a blackguard, Josse, I'm next to one.' On another occasion, he said to Watson: 'This church-yard, the cemetery of the Collegiate Church, must be enclosed; and we shall want a lot of railing.' The Doctor archly replied: ' That can't be, Jesse; there's railing enough in the church daily.' In his last illness, the parish-clerk came to see him. Joshua had lost the sight of one eye, and the clerk venturing to say that he thought the other eye was also gone, the dying man (who had remained silent and motionless for hours), with a flash of the old fire, shouted twice: 'Thou'rt a liar, Bob!' A few days afterwards, both eyes were closed in death. He died unmarried, in the sixty-eighth year of his age, and was buried at the south-west end and corner of the Collegiate Church. Poor Joshua! a very 'Ishmael' all his life, he found rest and peace at last. A man of many foibles and failings, he was free from the grosser vices, and in all the private relations of life he was exemplary. THE DAY OF DUPES: TRIUMPH OF CARDINAL RICHELIEUThis whimsical title has been given to the 11th of November 1630, on the occasion of the triumph of Cardinal Richelieu over his enemies, who imagined that they had succeeded in casting him to the ground, never again to rise. The intriguing and ambitious Marie de Medici had prevailed on her son, the fickle and weak-minded Louis XIII, to dismiss Richelieu from the office of prime-minister, and raise to that dignity the latter's mortal enemy, the Marshal de Marillac. The wily priest appears to have been fairly rendered prostrate, and unable to avert the ruin which seemed ready to fall on him, when he was persuaded by his friends to make one last effort to recover the favour of the king. With this view he proceeded to Versailles, then only a small hunting lodge, which Louis XIII had recently purchased, and had an interview with his sovereign. The result of this memorable visit was that Louis surrendered himself again into the cardinal's hands, with a feebleness similar to what he had previously shewn in dismissing him from his presence. But Richelieu, by this coup de main, succeeded in riveting the chains on Louis more firmly than they had been before, and established for himself an absolute sway, which he retained till his death. As may be expected, he did not fail to confirm his power by taking signal vengeance on his enemies, and among others, on the Marshal de Marillac, whom he caused ere long to be brought to the scaffold. BURNING OF THE 'SARAH SANDS'One of the finest examples on record, of the saving of human life by the maintenance of high discipline, during trying difficulties, was afforded during the burning of the Sarah Sands, a transport steamer employed by the government in 1857. She was on her passage from England to India, with a great part of the 54th Regiment of Foot on board, intended to assist in the suppression of the Indian mutiny; the number of persons was about 400, besides the ship's crew. The vessel, an iron steamer of 2000 tons burthen, arrived at a spot about 400 miles from Mauritius; when, at three in the afternoon on the 11th of November, the cargo in the hold was found to be on fire. Captain Castle, commanding the ship, and Lieutenant - Colonel Moffatt, commanding the troops, at once concerted plans for maintaining discipline under this terrible trial. Some of the men hauled up bale after bale of government stores from the hold; some took in sail, and brought the ship before the wind; some ran out lengths of hose from the fire-engine, and poured down torrents of water below. It soon became evident, however, that this water would not quench the flames, and that the smoke in the hold would prevent the men from longer continuing below. The colonel then ordered his men to throw overboard all the ammunition in the starboard magazine. But the larboard or port magazine was so surrounded with heat and smoke, that he hesitated to command the men to risk their lives there; and he therefore called for volunteers. A number of brave fellows at once stepped forward, rushed to the magazine, and cleared out all its contents, except a barrel or two of powder; several of them, overpowered with heat and smoke, fell by the way, and were hauled up senseless. The fire burst up through the decks and cabins, and was intensified by a fierce gale which happened to be blowing at the time. Captain Castle then resolved to lower the boats, and to provide for as many as he could. This was admirably done. The boats were launched without accident, the troops were mustered on deck, there was no rush to the boats, and the men obeyed the word of command with as much order as if on parade-the greater number of them embarking in the boats. A small number of women and children who were on board, were lowered into the life-boat. All these filled boats were ordered to remain within reach of the ship till further orders. The sailors then set about constructing rafts of spare spars, to be ready in case of emergency. Meanwhile the flames had made terrible progress; the whole of the cabins and saloons were one body of fire; and at nine in the evening the flames burst through the upper deck and ignited the mizzen rigging. During this fearful suspense, the barrel or two of powder left in one of the magazines exploded, and blew out the port-quarter of the ship-shewing what would have been the awful result had not the heroic men previously removed the greater part of the ammunition. As the iron bulk-head of the after-part of the vessel continued to resist the flames, Captain Castle resolved to avail himself of this serviceable aid as long as possible; to which end the men were employed for hours in dashing water against the bulk-head, to keep it cool. When fire seized the upper-rigging, soldiers as well as sailors rushed up with wet blankets, and allayed its fearful progress. This struggle between human perseverance and devastating flames continued until two o'clock in the morning, when, to the inexpressible delight of all, the fire was found to be lessening; and by daylight it was extinguished. The horrors of the situation were, however, not yet over. The after-part of the ship was a mere hollow burned shell; and as the gale still continued, the waves poured in tremendously. Some of the men were set to the pumps, some baled out water from the flooded hold with buckets; while others sought to prevent the stern of the ship from falling out by passing hawsers around and under it, and others tried to stop the leak in the port-quarter with spare sails and wet blankets. The water-tanks in the hold, having got loose, were dashed from side to side by the violence of the gale, and battered the poor ship still further. At two in the afternoon (twenty-three hours after the fire had been discovered), the life-boat was hauled alongside, and the women and children taken on board again. All the other boats, except the gig, were in like manner brought along-side, and the soldiers re-embarked; the gig had been swamped, but all the men in her were saved. During thirty-six hours more, nearly all the soldiers were assisting the sailors in working the pumps, and clearing the ship of water; while the captain succeeded at length in getting the ill-fated ship into such trim as to be manageable. He then steered towards the Mauritius, which he reached in eight days. The achievement was almost unparalleled, for the vessel was little else than a burned and battered wreck. Not a single person was lost; the iron bulk-head was the main material source of safety; but this would have been of little avail had not discipline and intrepidity been shewn by those on board. The sense of the 'honour of the flag' came out strikingly during the peril. When the ship was all in a blaze, it was suddenly recollected that the colours of the 54th were in the aft-part of the saloon. Quartermaster Richmond rushed down, snatched the Queen's colours, brought them on deck, and fainted with the heat and smoke; when recovered, he made another descent, accompanied by Private Wills, brought up the regimental colours, and again fainted, with a result which proved nearly fatal. CUSTOM OF KNIGHTLOW CROSSTo the philosophical student of history, and all who feel an interest in the progressive prosperity of our country, and the often slow and painful steps by which that prosperity has been reached, any custom, however insignificant in itself, which tends to throw light upon the doings of our ancestors, is of great interest. But in our search after such landmarks, as it were, of our country's history, we are too apt to overlook what is most patent to us all, and so it is that a custom which, in all probability, obtained in the days of our Saxon forefathers, long before William of Normandy set foot upon our land, is at the present day carried on close to us, unheeded and unknown to the majority of our readers. The custom to which we refer is the payment to the Lord of the Hundred of Knightlow of Wroth or Ward money for protection, and probably also in lieu of military service. The scene of these payments is Knightlow Cross, Stretton-on-Dunsmore, near Rugby, Warwickshire. Here, at the northern extremity of the village, in a field by what used to be the Great Holyhead Road, stands a stone, the remains of Knightlow Cross. The stone now to be seen is the mortice-stone of the ancient cross, and is similar to the stone still in existence at St. Thomas's Cross, between Clifton-upon-Dunsmore and Newton. The stone stands on a knoll or tumulus, having a fir-tree at either corner, and from it a fine view of the surrounding country is obtained; the spires of the ancient city of Coventry being plainly visible in the distance. It is a singular circumstance, that the field in which it stands is a freehold belonging to a Mr. Robinson of Stretton, but the mound upon which the stone stands belongs to the Lord of the Hundred, his Grace the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry. The mound is an ancient British tumulus, one of a chain (still or very lately) to be traced from High Cross-the ancient Roman station Bennis-southward down the Foss Road. The intermediate links are at Walston Brinklow, near Wittingbrook and Cloudesley Bush, but the latter, we regret to say, has been removed. Monday morning, the 11th of November 1862, was the day for the payment of this Wroth Silver, as it is called, and a drive in the gray light of a November morning, took us to the spot half an hour before sunrise, but not before groups of villagers and others had begun to collect to witness or take part in this curious old custom. The land-agent of the lord of the hundred arrived soon after, and proceeded at once to read the notice requiring the payment to be made, proclaiming that in default of payment, the forfeit would be 'twenty shillings for every penny, and a white bull with red ears and a red nose.' The names of the parishes and persons liable were then read out, and the amounts were duly thrown into the large basin-like cavity in the stone, and taken from thence by the attendant bailiff. After the ceremony, the actors in the scene-that is, those persons, numbering about forty, who paid the money into the stone-proceeded to the Frog Hall, where a substantial breakfast was provided for them at the expense of the Duke of Buccleuch. There is a tradition in the neighbourhood of the forfeiture of a white bull having been demanded and actually made. Of this, however, there is no record, and it is certain that, of late years, the pecuniary part of the forfeit only has been insisted upon. Respecting this custom, Dugdale, in his history of Warwickshire, gives the following account: There is also a certain rent due unto the Lord of this Hundred, called Wroth-money, or Wroth-money, or Swarff-penny, probably the same with Ward-penny. Denarii vicecomiti vel aliis castellanis persoluti ob castrorum presidium vel excubias agendas, says Sir H. Spelman in his Glossary, (fol. 565-566). This rent must be paid every Martinmas-day, in the morning, at Knightlow Cross, before the sun riseth: the party paying it must go thrice about the cross, and say, 'The Wrath Money,' and then lay it in the hole of the said cross before good witness, for if it be not duly performed, the forfeiture is 30s. and a white bull. Altogether, this custom forms a singular and interesting instance of a usage or rite surviving for centuries amidst revolutions, and civil wars, and changes of rulers and circumstances. Though its real origin has been lost, it still remains as a relic of feudal government, and may possibly be handed down to generations yet to come, as a memorial of a state of chronic warfare and depredation. |