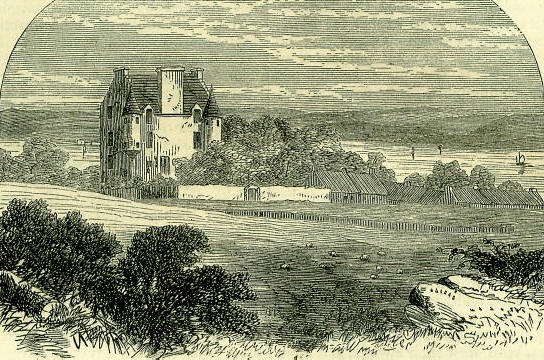

10th DecemberBorn: Thomas Holeroft, dramatist and translator, 1745, London; General Sir William Fenwick Williams, hero of Kars, 1800, Nova Scotia. Died: Llewellyn, Prince of Wales, killed, 1282; Edmund Gunter, mathematician, 1626; Jean Joseph Sue, eminent physician, 1792, Paris; Casimir Delavigne, French dramatist, 1843, Lyon; William Empson, editor of Edinburgh Review, 1852, Haileybury; Tommaso Grossi, Italian poet, 1853, Florence; Dr. Southwood Smith, author of works on sanitary reform, 1861, Florence. Feast Day: St. Eulalia, virgin and martyr, about 304. St. Melchiades, pope, 314. LLEWELLYN, THE LAST NATIVE PRINCE OF WALESThe title of 'Prince of Wales' has entirely changed its character. Originally, it was applied to a native sovereign. In the ninth century, when the Danes and Saxons had completely broken the power of the Britons in England, Wales was still in the hands of the Cymri, a branch of the same stock as the Britons; and it was governed by three brothers, with the dignity of princes-the prince of North Wales having precedence of the others in rank. It was, however, a very stormy and unsettled rule; for we find that, during the next three centuries, the princes of Wales were often obliged to pay tribute to the Saxon, Danish, and Norman rulers of England; and, moreover, the princes were frequently quarrelling among themselves, overstepping each other's landmarks, and breaking agreements without much scruple. At length one prince, Llewellyn, rose superior to the rest, and was chosen by the general voice of the people sovereign of Wales in 1246. The border district between the two countries, known as the Marches, was the scene of almost incessant conflicts between the English and Welsh, let who might be king in the one country, or prince in the other. There is a passage in Fuller, illustrative of the hardships endured by the English soldiers during a raid across the Marches nearly to the western part of the principality: I am much affected with the ingenuity [ingenuousness] of an English nobleman, who, following the camp of King Henry III in these parts (Caernarvonshire), wrote home to his friends, about the end of September 1245, the naked truth, indeed, as followeth: 'We lie in our tents, watching, fasting, praying, and freezing. We watch, for fear of the Welshmen, who are wont to invade us in the night; we fast, for want of meat, for the half-penny loaf is worth five pence; we pray to God to send us home speedily; and we freeze for want of winter garments, having nothing but thin linen between us and the wind.' On the other hand, the Welsh were always ready to take advantage of any commotions across the border. In 1268, Llewellyn was compelled to accept terms which Henry III imposed upon him, and which rendered him little else than a feudal vassal to the king of England. When Henry died, and Edward I became king, Llewellyn was summoned to London, to render homage to the new monarch. The angry blood of the Welshman chafed at this humiliation; but he yielded-more especially as Edward held in his power the daughter of Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, to whom Llewellyn was betrothed, and he could only obtain her by coming to London. In 1278, Llewellyn and the lady were married, the king himself giving away the bride. The Prince and Princess of Wales went to their future home in the principality. Their happiness, however, was short-lived: the princess died in giving birth to a daughter, who afterwards ended her days as a nun in a Lincolnshire convent. Peace did not long endure between Llewellyn and Edward. A desolating war broke out, marked by much barbarity on both sides. Llewellyn's friends fell away one by one, and made terms with the powerful king of England. The year 1282 saw the close of the scene. While some of his adherents were combating the Earl of Gloucester and Sir Edmund Mortimer in South Wales, Llewellyn himself was fighting in the north. Leaving the bulk of his soldiers, and coming almost unattended to Builth, he fell into an ambush, which cost him his life. Dr. Powel, in 1584, translated into English an account of the scene, written by Caradoc of Llanfargan: The prince departed from his men, and went to the valley with his squire alone, to talk with certain lords of the country, who had promised to meet him there. Then some of his men, seeing his enemies come down from the hill, kept the bridge called the Pont Orewyn, and defended the passage manfully, till one declared to the English-men where a ford was, a little beneath, through the which they sent a number of their men with Elias Walwyn, who suddenly fell upon them that defended the bridge, in their backs, and put them to flight. The prince's esquire told the prince, as he stood secretly abiding the coming of such as promised to meet him in a little grove, that he heard a great noise and cry at the bridge; and the prince asked whether his men had taken the bridge, and he said, 'Yes.' 'Then,' said the prince, 'I pass not if all the power of England were on the other side.' But suddenly, behold the horsemen about the grove; and as he would have escaped to his men, they pursued him so hard that one Adam Francton ran him through with a staff, being unarmed, and knew him not. And his men being but a few, stood and fought boldly, looking for their prince, till the Englishmen, by force of archers, mixed with the horsemen, won the hill, and put them to flight. And as they returned, Francton went to despoil him whom he had slain; and when he saw his face, he knew him very well, and stroke off his head, and sent it to the king at the abbey of Conway, who received it with great joy, and caused it to be set upon one of the highest turrets of the Tower of London. Thus closed the career of Llewellyn, the last native sovereign of Wales. Edward I speedily brought the whole principality under his sway, and Wales has ever since been closely allied to England. Edward's queen gave birth to a son in Caernarvon Castle; and this son, while yet a child, was formally instituted Prince of Wales. It thence-forward became a custom, departed from in only a few instances, to give this dignity to the eldest son, or heir-apparent of the English king or queen. The title is not actually inherited; it is conferred by special creation and investiture, generally soon after the birth of the prince to whom it relates. It is said, by an old tradition, that Edward I, to gratify the national feelings of the Welsh people, promised to give them a prince without blemish on his honour, Welsh by birth, and one who could not speak a word of English. He then, in order to fulfil his promise literally, sent Queen Eleanor to be confined at Caernarvon Castle, and the infant born there had, of course, all the three characteristics. Be this tradition true or false, the later sovereign cared very little whether the Princes of Wales were acceptable or not to the people of the principality. In the mutations of various dynasties, the Prince of Wales was not, in every case, the eldest son and heir-apparent; and in two instances, there was a princess without a prince. Henry VIII gave this title to his two daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, in succession; but the general rule has been as above stated. It may be useful here to state, in chronological order, the eighteen Princes of Wales, from the time of Edward I to that of Victoria. We shall construct the list from details given in Dr. Doran's Book of the Princes of Wales. Each prince has a kind of surname, according to the place where he was born. Besides the above, there were two wanderers, who were regarded in many parts of Europe as Princes of Wales, and certainly were so in right of birth. These were the son and grandson of the fugitive James II - James Francis Edward, born 1688, and known afterwards as the 'Old Pretender,' died 1765; and his son, Charles Edward, born 1720, and for a long period known as the 'Young Pretender,' died 1788. THE MISSISSIPPI SCHEMEOn the 10th of December 1720, John Law, late comptroller-general of the finances of France, retreated from Paris to his country-seat of Guermande, about fifteen miles distant from the metropolis, and in a few days afterwards quitted the kingdom, never again to return. A few months before, he had enjoyed a position and consideration only comparable with that of a crowned monarch-if, indeed, any sovereign ever received such eager and importunate homage, as for a time was paid to the able and adventurous Scotchman. The huge undertaking projected by Law, and known by the designation of the Mississippi Scheme, was perhaps one of the grandest and most comprehensive ever conceived. It not only included within its sphere of operations the whole colonial traffic of France, but likewise the superintendence of the Mint, and the management of the entire revenues of the kingdom. The province of Louisiana, in North America, then a French possession, was made over by the crown to the 'Company of the West,' as the association was termed, and the most sanguine anticipations were entertained of the wealth to be realized from this territory, which was reported, amid other resources, to possess gold-mines of mysterious value. In connection with the same project, a bank, established by law, under the sanction of the Duke of Orleans, then regent of France, promised to recruit permanently the impoverished resources of the kingdom, and diffuse over the land, by an unlimited issue of paper-money, a perennial stream of wealth. For a time these sanguine anticipations seemed to be fully realized. Prosperity and wealth to a hitherto unheard of extent prevailed throughout France, and Law was, for a short period, the idol of the nation, which regarded him as its good genius and deliverer. Immense fortunes were realised by speculations in Mississippi stock, the price of which rose from 500 livres, the original cost, to upwards of 10,000 livres by the time that the mania attained its zenith. A perfect frenzy seemed to take possession of the public mind, and to meet the ever-increasing demand, new allotments of stock were made, and still the supply was inadequate. Law's house in the Rue Quinquempoix, in Paris, was beset from morning to night by eager applicants, who soon by their numbers blocked up the street itself and rendered it impassable. All ranks and conditions of men-peers, prelates, citizens, and mechanics, the learned and the unlearned, the plebeian and the aristocrat-flocked to this temple of Plutus. Even ladies of the highest rank turned stockjobbers, and vied with the rougher sex in eagerness of competition. So utterly inadequate did the establishment in the Rue Quinquempoix prove for the transaction of business, that Law transferred his residence to the Place Vendôme, where the tumult and noise occasioned by the crowd of speculators proved such a nuisance, and impeded so seriously the procedure in the chancellor's court in that quarter, that the monarch of stockjobbers found himself obliged again to shift his camp. He, accordingly, purchased from the Prince of Carignan, at an enormous price, the Hotel de Soissons, in which mansion, and the beautiful and extensive gardens attached, he held his levees, and allotted the precious stock to an ever-increasing and enthusiastic crowd of clients. With such demands on his time and resources, it became absolutely impossible for him to gratify one tenth of the applicants for shares, and the most ludicrous stories are told of the stratagems employed to gain an audience of the great financier. One lady made her coachman overturn her carriage when she saw Mr. Law approaching, and the ruse succeeded, as the gallantry of the latter led him instantly to proffer his assistance, and invite the distressed fair one into his mansion, where, after a little explanation, her name was entered in his books as a purchaser of stock. Another female device to procure an interview with Law, by raising an alarm of fire near a house where he was at dinner, was not so fortunate, as the subject of the trick suspecting the motive, hastened off in another direction, when he saw the lady rushing into the house, which he and his friends had emerged from on the cry of fire being raised. The terrible crash at last came. The amount of notes issued from Law's bank more than doubled all the specie circulating in the country, and great difficulties were experienced from the scarcity of the latter, which began both to be hoarded up and sent out of the country in large quantities. Severe and tyrannical edicts were promulgated, threatening heavy penalties for having in possession more than 500 livres or £20 in specie; but this only increased the embarrassment and dissatisfaction of the nation. Then came an ordinance reducing gradually the value of the paper currency to one half, followed by the stoppage of cash-payments at the bank; and at last the whole privileges of the Mississippi Company were withdrawn, and the notes of the bank declared to be of no value after the 1st of November 1720. Law had by this time lost all influence in the councils of government, his life was in danger from an infuriated and disappointed people, and he was therefore fain to avail himself of the permission of the regent (who appears still to have cherished a regard for him) to retire from the scene of his splendour and disgrace. After wandering for a time through various countries, he proceeded to England, where he resided for several years. In 1725, he returned again to the continent, fixed his residence at Venice, and died there almost in poverty, on 21st March 1729. Such was the end of the career of the famous John Law, who, of all men, has an undoubted title to be ranked as a prince of adventurers. In him the dubious reputation formerly enjoyed by Scotland, of sending forth such characters, was fully maintained. He was descended from an ancient family in Fife; but his father, William Law, in the exercise of the business of a goldsmith and banker in Edinburgh, gained a considerable fortune, enabling him to purchase the estate of Lauriston, in the parish of Cramond, which was inherited by his eldest son John.  Lauriston Castle, as it appeared at the close of the last century The ancient mansion of Lauriston Castle on this property, beautifully situated near the Firth of Forth, is believed to have been erected in the end of the sixteenth century, by Sir Archibald Napier of Merchiston, father of the celebrated inventor of logarithms, and then proprietor of Lauriston. It is represented in the accompanying engraving. In recent years, the building was greatly enlarged and embellished by Andrew Rutherfurd, Lord Advocate for Scotland, and subsequently one of the judges of the Court of Session. Law is said to have retained throughout a strong affection for his patrimonial property, and a story in reference to this is told of a visit paid to him by the Duke of Argyle in Paris, at the time when his splendour and influence were at the highest. As an old friend, the duke was admitted directly to Mr. Law, whom he found busily engaged in writing. The duke entertained no doubt that the great financier was busied with a subject of the highest importance, as crowds of the most distinguished individuals were waiting in the anterooms for an audience. Great was his grace's astonishment when he learned that Mr. Law was merely writing to his gardener at Lauriston regarding the planting of cabbages at a particular spot! Of Law's general character, it is not possible to speak with great commendation. He appears to have been through life a libertine and gambler, and in the latter capacity he supported himself for many years, both before and after his brief and dazzling career as a financier and political economist. In his youth, he had served an apprentice-ship to monetary science under his father, and a course of travel and study, aided by a vigorous and inventive, but apparently ill-regulated intellect, enabled him subsequently to mature the stupendous scheme which we have above detailed, and succeed in indoctrinating with his views the regent of France. His first absence from Great Britain was involuntary, and occasioned by his killing, in a duel, the celebrated Beau Wilson (see following article), and thus being obliged to shelter himself by flight from the vengeance of the law. He then commenced a peregrination over the continent, and after a long course of rambling and adventure, settled down at Paris about the period of death of Louis XIV. A pardon for the death of Wilson was sent over to him from England in 1719. BEAU WITSONTowards the end of the reign of William III, London society was puzzled by the appearance of a young aspirant to fashionable fame, who soon became the talk of the town from the style in which he lived. His house was furnished in the most expensive manner; his dress was as costly as the most extravagant dandy could desire, or the richest noble imitate; his hunters, hacks, and racers were the best procurable for money; and he kept the first of tables, dispensing hospitality with a liberal spirit. And all this was done without any ostensible means. All that was known of him was, that his name was Edward Wilson, and that he was the fifth son of Thomas Wilson, Esq., of Keythorpe, Leicestershire, an impoverished gentleman. Beau Wilson, as he was called, is described by Evelyn as a very young gentleman, 'civil and good-natured, but of no great force of understanding,' and 'very sober and of good fame.' He redeemed his father's estate, and portioned off his sisters. When advised by a friend to invest some of his money while he could, he replied, that however long his life might last, he should always be able to maintain himself in the same manner, and therefore had no need to take care for the future. All attempts to discover his secret were vain; in his most careless hours of amusement he kept a strict guard over his tongue, and left the scandalous world to conjecture what it pleased. Some good-natured people said he had robbed the Holland mail of a quantity of jewelry, an exploit for which another man had suffered death. Others said he was supplied by the Jews, for what purpose they did not care to say. It was plain he did not depend upon the gaming-table, for he never played but for small sums-and he was to be found at all times, so it was not to be wondered at that it came to be believed that he had discovered the philosopher's stone. How long he might have pursued his mysterious career, it is impossible to say: it was cut short by another remarkable man on the 9th of April 1694. On that day, Wilson and a friend, one Captain Wightman, were at the 'Fountain Inn,' in the Strand, in company with the celebrated John Law (see preceding article), who was then a man about town. Law left them, and the captain and Wilson took coach to Bloomsbury Square. Here Wilson alighted, and Law reappeared on the scene; as soon as they met, both drew their swords, and after one pass the Beau fell wounded in the stomach, and died without speaking a single word. Law was arrested, and tried at the Old Bailey for murder. The cause of the quarrel did not come out, but there is little doubt that a woman was in the case. Evelyn says: The quarrel arose from his (Wilson's) taking away his own sister from lodging in a house where this Law had a mistress, which the mistress of the house thinking a disparagement to it, and losing by it, instigated Law to this duel. Law declared the meeting was accidental, but some threatening letters from him to Wilson were produced on the trial, and the jury believing that the duel was unfairly conducted, found him guilty of murder, and he was condemned to death. The sentence was commuted to a fine, on the ground of the offence amounting only to manslaughter; but Wilson's brother appealed against this, and while the case was pending a hearing, Law contrived to escape from the King's Bench, and reached the continent in safety, notwithstanding a reward offered for his apprehension. He ultimately received a pardon in 1719. Those who expected Wilson's death would clear up the mystery attached to his life, were disappointed. He left only a few pounds behind him, and not a scrap of evidence to enlighten public curiosity as to the origin of his mysterious resources. While Law was in exile, an anonymous work appeared which professed to solve the riddle. This was The Unknown Lady's Pacquet of Letters, published with the Countess of Dunois' Memoirs of the Court of England (1708), the author, or authoress of which, pretends to have derived her information from an elderly gentlewoman, 'who had been a favourite in a late reign of the then she-favourite, but since abandoned by her.' According to her account, the Duchess of Orkney (William III's mistress) accidentally met Wilson in St. James's Park, incontinently fell in love with him, and took him under her protection. The royal favourite was no niggard to her lover, but supplied him with funds to enable him to shine in the best society, he undertaking to keep faithful to her, and promising not to attempt to discover her identity. After a time, she grew weary of her expensive toy, and alarmed lest his curiosity should overpower his discretion, and bring her to ruin. This fear was not lessened by his accidental discovery of her secret. She broke off the connection, but assured him that he should never want for money, and with this arrangement he was forced to be content. The 'elderly gentlewoman,' however, does not leave matters here, but brings a terrible charge against her quondam patroness. She says, that having one evening, by her mistress' orders, conducted a stranger to her apartment, she took the liberty of playing eaves-dropper, and heard the duchess open her strong-box and say to the visitor: Take this, and your work done, depend upon another thousand and my favour for ever! Soon afterwards poor Wilson met his death. The confidante went to Law's trial, and was horrified to recognise in the prisoner at the bar the very man to whom her mistress addressed those mysterious words. Law's pardon she attributes to the lady's influence with the king, and his escape to the free use of her gold with his jailers. Whether this story was a pure invention, or whether it was founded upon fact, it is impossible to determine. Beau Wilson's life and death must remain among unsolved mysteries. |