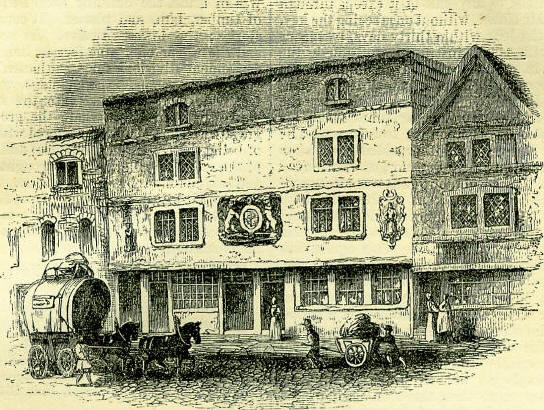

9th DecemberBorn: Gustavus Adolphus the Great, of Sweden, 1594; John Milton, poet, 1608, London; William Whiston, divine, translator of Josephus, 1667, Norton, Leicestershire; Philip II of Spain, 1683, Versailles. Died: Pope Pius IV, 1565; Sir Anthony Vandyck, painter, 1641, London; Pope Clement IX, 1669; Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, 1674, Rome; John Reinhold Forster, naturalist, and voyager, 1798, Halle; Joseph Bramah, inventor of the Bramah press, &c., 1814, Pimlico; Charles Macfarlane, historian, 1858, London; John O'Donovan, LL.D., Irish historical antiquary, 1861, Dublin. Feast Day: The Seven Martyrs at Samosata, 297. St. Leocadia, virgin and martyr, 304. St. Wulfhilde, virgin and abbess, 990. MILTON'S BIRTHPLACE, AND ITS VICINITYThe house in which John Milton was born, on the 9th December 1608, no longer exists; but its site can be determined within a few yards. His father was a scrivener, who carried on business in Bread Street, Cheapside; and here was born the child who was destined to become one of the world's greatest poets. 'In those days,' says Professor Masson in his Life of Milton, 'houses in cities were not numbered, as now; and persons in business, to whom it was of consequence to have a distinct address, effected the purpose by exhibiting over the door some sign or emblem. This fashion, now left chiefly to publicans, was once common to all trades and professions. Booksellers and printers, as well as grocers and mercers, carried on their business at the 'Cross Keys,' the 'Dial,' the 'Three Pigeons,' the 'Ship and Black Swan,' and the like, in such and such streets; and every street in the populous part of such a city as London presented a succession of these signs, fixed or swung over the doors. The scrivener Milton had a sign as well as his neighbours. It was an eagle with outstretched wings; and hence his house was known as the 'Spread Eagle,' in Bread Street.' Now, it appears that there is a little inlet or court on the east side of Bread Street, three or four doors from Cheapside, which was once called Spread Eagle Court,' but which has now no name distinct from that of the street itself; and Professor Masson thinks, not without good grounds, that this spot denotes pretty nearly the site of John Milton's birthplace. Bread Street is almost exactly in the centre of that large area of buildings which was consumed by the great fire of 1666; and the house in question was one of those destroyed. Before that year (although Paradise Lost was not yet published), Milton's name had become famous; and Anthony à Wood states that strangers liked to have pointed out to them the house where he first saw the light. The church of Allhallows, close by, still contains the register of Milton's baptism. It is interesting to trace the changes which that part of the city has undergone since the old days. Courtiers, poets, wits, and gallants were once quite at home in a place where almost every house is now a wholesale warehouse for textile goods. Milton himself, as we know from the details of his life, after his boyish-days in Bread Street, lived in Barbican, in Jewin Street, in Bartholomew Close, and in Little Britain, besides various places at the west end of the town. Bread Street was occupied as a bread-market in the time of Edward I; and other streets turning out of Cheapside or situated near it, such as Milk Street, Wood Street, and Hosier Lane, were in like manner markets for particular kinds of commodities. William Stafford, Earl of Wiltshire, had a mansion in Bread Street, towards the close of the fifteenth century. Stow says: On the west side of Bread Street, amongst divers fair and large houses for merchants, and fair inns for passengers, had ye one prison-house pertaining to the sheriffs of London, called the Compter, in Bread Street; but in the year 1555, the prisoners were removed from thence to one other new Compter in Wood Street, provided by the city's purchase, and built for that purpose. The 'fair inns for travellers' were the 'Star,' the 'Three Cups,' and the ' George.' But more famous than these was the 'Mermaid,' thought by some writers to have been in Friday Street, but more generally considered to have been in Bread Street. It was a tavern where Shakspeare, Ben Jonson, Beaumont, Fletcher, Donne, and other choice spirits assembled, in the time of Queen Elizabeth. What things have we seen Done at the Mermaid! said one of them; and there can be little doubt that wit flashed and sparkled there merrily; for witty courtiers, as well as witty authors, swelled the number. All are gone now-the bread-market, the Compter, the earl's mansion, the inns for travellers, the renowned 'Mermaid,' and the poet's birth-place; no wealthy merchants, even, 'live' in Bread Street, for their private residences are far away from city bustle. Bread Street is now almost exclusively occupied by the warehouses of wholesale dealers in linens, cottons, woollens, silks, and all the multifarious articles, composed of these, belonging to dress. Not only are nearly all the sixty or seventy houses so occupied, but in some cases as many as seven wholesale firms will rent the rooms of one house. And so it is in nearly all the streets that surround Bread Street. Where almost every house is now a warehouse, there were once places or people that one likes to read and hear about. Take Cheapside ('Chepe,' or 'West Cheaping') itself. This has always been the greatest thoroughfare in the city of London; and nearly all the city pageants of old days passed through it. It contained the shops of the wealthy mercers and drapers from very early times. Lydgate, in his London Lykpenny, written in the fifteenth century, makes his hero say: Then to the Chepe I began me drawne, Where moth people I saw for to stand. One ofred me velvet, sylke, and lawne; An other he taketh me by the hande, 'Here is Parys thread, the finest in the land!' This is curious, as tending to spew that the mercers or their apprentices were wont to solicit custom at their shop-doors, as butchers still do. There was once the 'Conduit' in Cheapside, near which Wat Tyler beheaded some of his prisoners in 1381, and Jack Cade beheaded Lord Saye in 1450. The cross in Cheapside, one of those erected by Edward in memory of his queen, Eleanor, was near Poultry. Where Bow Church now stands, Edward I. and his queen sat in a wooden gallery to see one of the city pageants pass through Cheapside. An accident on that occasion led to the construction of a stone gallery; and when all this part of the city was laid in ashes in 1666, Sir Christopher Wren included a pageant-gallery in the front of his beautiful steeple of Bow Church, just over the arched entrance. That gallery, in which Charles II and Queen Anne were royal visitors, is still existing, though no longer used in a similar way. Concerning the street itself, Howes, writing about 1631, said: At this time and for divers years past, the Goldsmith's Row' (a jutting row of wooden tenements), 'in Cheapside, was very much abated of her wonted store of goldsmiths, which was the beauty of that famous street; for the young gold-smiths, for cheapnesse of dwelling, take their houses in Fleet Street, Holborne, and the Strand, and in other streets and suburbs; and goldsmiths' shops were turned to milliners, linen-drapers, and the like. Two centuries or more ago, therefore, Cheapside, which had already been a mart for mercery and drapery, became still more extensively associated with those trades. It was about that time that Charles I dined on one occasion with Mr. Bradborne, one of the wealthy Cheapside mercers. If we turn into any one of the streets branching from this great artery, we should find strange contrasts to the old times now exhibited. In Friday Street, now occupied much in the same way as Bread Street, there was at one time a fish-market on Fridays; the 'Nag's Head,' at the corner of Cheapside, was concerned in some of the notable events of Elizabeth's reign; and a club held the meeting which led eventually to the establishment of the Bank of England. In Old Change-once the 'Old Exchange,' for the receipt of bullion to be coined; and where dealers in 'ventilating corsets' and 'elastic crinolines' now share most of the houses with mercers and drapers -Lord Herbert, of Cherbury, had a fine house and garden in the time of James I; and early in the last century, there was a colony of Armenian merchants there. In Bow Lane, Tom Coryat, the eccentric traveller, died in 1617. In Soper's Lane, changed, after the great fire, to Queen Street, the 'pepperers' used to reside in some force; they were the wholesale-dealers in drugs and spices. In the Old Jewry, Sir Robert Clayton had a fine house in the time of Charles II; and in this street Professor Porson died. Bucklersbury, where Sir Thomas More lived, and where his daughter Margaret was born, was a famous place for druggists, apothecaries, herbalists, and dealers in 'simples'. BRAMAH LOCK-PICKINGJoseph Bramah, the mechanical engineer, is better remembered, perhaps, in connection with lock-making than with any other department of his labours, although others were of a more important character. Born in 1749, he was intended, like his brothers, to follow the avocation of their father, who was a farmer in Yorkshire; but a preference for the use of mechanical tools led him to the trade of a carpenter and cabinet-maker. He became an inventor, and then a manufacturer, of valves and other small articles in metal-work; and in 1784, he devised the 'impregnable' lock, which has ever since obtained so much celebrity. Then ensued a long series of inventions in taps, tubes, pumps, fire-engines, beer-engines for taverns, steam-engines, boilers, fire-plugs, and the like. His hydraulic-press is one of the most valuable contributions ever made by inventive skill to manufacturing and engineering purposes. His planing machine for wood and metal surfaces has proved little less valuable. He made a machine for cutting several pen-nibs out of one quill, and a machine for numbering bank-notes, and devised a new mode of rendering timber proof against dryrot. In the versatile nature of his mechanical genius, he bears a strong resemblance to the elder Brunel. His useful life, passed in an almost incessant series of inventions, was brought to a close, characteristically enough, on December 9th, 1814, by a cold caught while using his own hydraulic-press for uprooting trees in Holt Forest. The reason why Bramah's locks have been more publicly known than any other of his inventions is, because there was a mystery or puzzle connected with them. How to lock a door which can be opened only by means of a proper key, is a problem nearly four thousand years old; for Denon, in his great work on Egypt, has given figures of a lock found depicted among the bas-reliefs which decorate the great temple at Karnak: it is precisely similar in principle to the wooden locks now commonly used in Egypt and Turkey. The principle is simple, but exceedingly ingenious. Shortly before Mr. Bramah's time, English inventors sought to improve upon the old Egyptian locks; but he struck into a new path, and devised a lock of singularly ingenious and complex character. To open it without its proper key, would be (to use his own language): as difficult as it would be to determine what kind of impression had been made in any fluid, when the cause of such impression was wholly unknown; or to determine the separate magnitudes of any given number of unequal sub-stances, without being permitted to see them; or to counterfeit the tally of a banker's cheque, without having either part in possession. One particular lock made by him, having thirteen small pieces of mechanism called, 'sliders,' was intended to defy lock-pickers to this extent: that there were the odds of 6,227,019,500 to 1, against any person, unprovided with the proper key, finding the means of opening the lock without injuring it! Mr. Chubb, and many other persons both in England and America, invented locks which attained, by different means, the same kind of security sought by Mr. Bramah; and it became a custom with the makers to challenge each other-each daring the others to pick his lock. The Great Exhibition of 1851 brought this subject into public notice in a singular way. An American lockmaker, Mr. Hobbs, declared openly at that time that all the English locks, including Bramah's, might be picked; and, in the presence of eleven witnesses, he picked one of Chubb's safety-locks in twenty-five minutes, without having seen or used the key, and without injuring the lock. After much controversy concerning the fairness or unfairness of the process, a bolder attempt was made. There had, for many years, been exhibited in the shop-window of Messrs Bramah (representatives of the original Joseph Bramah), a padlock of great size, beauty, and complexity; to which an announcement was affixed, offering a reward of two hundred guineas to any person who should succeed in picking that lock. Mr. Hobbs accepted the challenge; the lock was removed to an apartment specially selected; and a committee was appointed, chosen in equal number by Messrs Bramah and Mr. Hobbs, to act as arbitrators. The lock was screwed to, and between two boards, and so fixed and sealed that no access could be obtained to any part of it except through the keyhole. Mr. Hobbs, without once seeing the key, was to open the lock within thirty days, by means of groping with small instruments through the keyhole, and in such way as to avoid injury to the lock. By one curious clause in the written agreement, Messrs Bramah were to be allowed to use the key in the lock at any time or times when Mr. Hobbs was not engaged upon it; to insure that he had not, even temporarily, either added to or taken from the mechanism in the interior, or disarranged it in any way. This right, however, was afterwards relinquished; the key was kept by the committee during the whole of the period, under seal; and the keyhole was also sealed up whenever Mr. Hobbs was not engaged upon it. This agreement, elaborate enough for a great commercial enterprise, instead of merely the picking of a lock, was signed in July 1851; and Mr. Hobbs began operations on the 24th. For sixteen days, spreading over a period of a month, he shut himself in the room, trying and testing the numerous bits of iron and steel that were to enable him to open the lock; the hours thus employed were fifty-one in number, averaging rather more than three on each of the days engaged. On the 23rd of August Mr. Hobbs exhibited the padlock open, in presence of Dr. Black, Professor Cowper, Mr. Edward Bramah, and Mr. Bazalgette. In presence of two of these gentlemen, he then both locked and unlocked it, by means of the implements which he had constructed, without over having once seen the key. On the 29th he again locked and unlocked it, under the scrutiny of all the members of the committee. On the 30th the proper key was unsealed, and the lock opened and shut with it in the usual way: thus shewing that the delicate mechanism of the lock had not been injured. Mr. Hobbs then produced the instruments which he used. The makers of the lock took exception to some of the proceedings, as not being in accordance with the terms of the challenge but the arbitrators were unanimous in their decision that Mr. Hobbs had fairly achieved his task. The two hundred guineas were paid. Of the stormy controversy that arose among the lock-makers, we have not here to speak: suffice it to say, that the lock which was thus picked was one which Joseph Bramah had made forty years earlier. All the intricate details on which the lock-picker was engaged, were contained within a small brass barrel about two inches long. THE FORTUNE THEATRE1621, Dec. 9, Md.-This night att 12 of the clock the Fortune was burnt.' Such is the brief account given by Alleyn, in his diary, of the destruction of his theatre after an existence of twenty-one years. In two hours the building was burned to the ground, and all its contents destroyed. The Fortune stood on the east of Golding (now Golden) Lane, Barbican, and was built in the year 1599 for Alleyn and his partner Henslowe, by Peter Streete, citizen and carpenter. The contract for its erection has been preserved, and we find it therein stipulated that the frame of the house was to be set square, and contain fourscore feet 'every way square' without, and fifty feet square within. The foundation, reaching a foot above the ground, was of brick, the building itself being constructed of timber, lath, and plaster. It consisted of three stories; the lowest, twelve, the second, eleven, and the upper one, nine feet in height; with four convenient divisions for 'gentlemen's rooms' and twopenny rooms.' 'The stage was forty-three feet wide, and projected into the middle of the yard-the open space where the groundlings congregated. The theatre was covered with tiles, instead of being thatched like the Globe, and the supports of the rooms or galleries were wrought like pilasters, and surmounted by carved satyrs. Streete contracted to do all the work, except the painting, for £440, but the entire cost was considerably more. Alleyn's pocket-book contains the following memorandum, made in 1610: What the Fortune cost me in November 1599: So it hath cost me in all for the leas - £880 Bought the inheritance of the land of the Gills of the Isle of Man within the Fortune, and all the howses in Wight Cross Street, June 1610, for the sum of £340. Bought John Garret's leas in reversion from the Gills for twenty-one years, for £100, so in all it cost me £1320. Blessed be the Lord God Everlasting. While the Fortune was in course of erection, a complaint was laid by sundry persons against 'building of the new theatre,' which led to an order in council limiting the theatres to be allowed to the Globe on the Surrey side, and the Fortune on the Middllesex side of the river-the latter being licensed, contingent on the Curtain Theatre, in Shoreditch, being pulled down or applied to other uses. The performances were only to take place twice a week; and the house was on no account to be opened on Sundays, during Lent, or 'at such time as any extraordinary sickness shall appear in or about the city.' In May 1601, the 'Admiral's servants' were transferred from the Curtain to Alleyn's new house, where they appear to have prospered. After it was burned down, it was rebuilt with brick, and the shape altered from square to round; and, in 1633, Prynne speaks of it as lately re-edified and enlarged. When Alleyn founded Dulwich College (the charity from which his own profession have been so strangely excluded), the Fortune formed part of its endowment, and the funds of the college suffered greatly when the theatre was closed during the Civil War. In 1649, some Puritan soldiers destroyed the interior of the house; and the trustees of the college finding it hopeless to expect any rent from the lessees, took the theatre into their own hands. A few years later, they determined to get rid of it altogether, and inserted an advertisement in the Mercurius Politicus of February 14, 1661, to the following effect: The Fortune Playhouse, situate between White Cross Street and Golding Lane, in the parish of St. Giles, Cripplegate, with the ground belonging, is to be let to be built upon; where twenty-three tenements may be erected, with gardens, and a street may be cut through for the better accommodation of the buildings. From this, it may be judged that the theatre occupied considerable space. There are no signs of any gardens now, the site of the theatre is marked by a plaster-fronted building bearing the royal arms, represented in the accompanying engraving; and the memory of the once popular playhouse is preserved in the adjacent thoroughfare called Playhouse Yard.  The Fortune Theater as it appeared in 1790 |