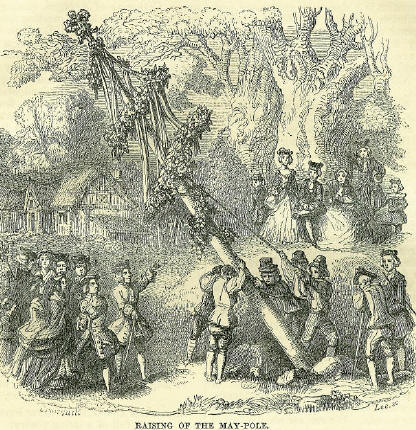

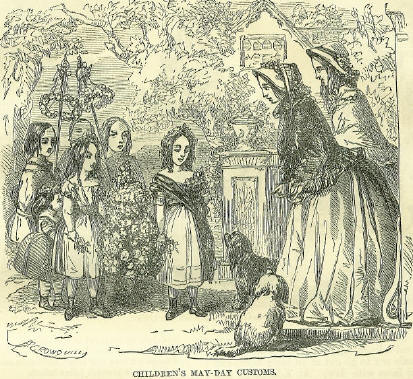

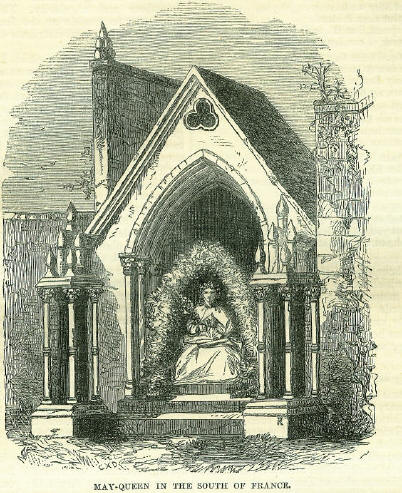

1st MayBorn: William Lilly, astrologer, 1602, Diseworth; Joseph Addison, miscellaneous writer, 1672, Milston, near Amesbury, Wilts; Sebastian de Vauban, 1633, Nivernois; Arthur, Duke of Wellington, 1769; Dr. John Woodward, naturalist, 1665, Derbyshire. Died: Arcadius, emperor of the East, 408; Maud, Queen of England, 1118; Pope Pius V, 1572; John Dryden, poet, 1700, London; Francois de Paris, 1727, Paris; Miss Richmal Mangnall, author of Miscellaneous Questions, &c., 1820. Feast Day: St. Philip and St. James the Less, apostles. St. Andeolus, martyr, 208. Saints Acius and Acheolus, martyrs, of Amiens, about 290. St. Amator, Bishop of Auxerre, 418. St. Briocus, of Wales, about 502. St. Sigismund, King of Burgundy, about 517. St. Marcon, abbot of Nanteu, in Normandy, 558. St. Asaph, abbot and bishop at Llanelwy, in North Wales, about 590. May 1st is a festival of the Anglican church, in honour of St. Philip and St. James the Less, apostles. ST. ASAPHAsaph is one of those saints who belong to the fabulous period, and whose history is probably but a legend altogether. According to the story, there was, in the sixth century, a bishop of Glasgow called Kentigern, called also by the Scots St. Mungo, who was driven from his bishopric in 543, and took refuge in Wales with St. David. Kentigern also was a saint; so the two saints wandered about Wales for some time seeking unsuccessfully for a convenient spot to build a church for the fugitive, and had almost given up the search in despair, when the place was miraculously pointed out to them through the agency of a wild boar. It was a piece of rising ground on the banks of the little river Elwy, a tributary of the Clwyd, and Kentigern built upon it a small church of wood, which, from the name of the river, was called Llanelwy, and afterwards established a monastery there, which soon became remarkable for its numerous monks. Among these was a young Welshman, named Asaph, who, by his learning and conduct, became so great a favourite with Kentigern, that when the latter established an episcopal see at Llanelwy, and assumed the dignity of a bishop, he deputed to Asaph the government of the monastery. More than this, when at length St. Kentigern's enemies in Scotland were appeased or silenced, and he was recalled to his native country, he resigned his Welsh bishopric to Asaph, who thus became bishop of Llanelwy, though what he did in his episcopacy, or how long he lived, is equally unknown, except that he is said, on very questionable authority, to have compiled the ordinances of his church, and to have written a life of his master, St Kentigern, as well as some other books. We can only say that nobody is known to have ever seen any such works. After his death, no bishops of Llanelwy have been recorded for a very long period of years-that is, till the middle of the twelfth century. The church and see still retained the name of Llanelwy, which, the supposed second bishop having been canonized, was changed at a later period to St. Asaph, by which name it is still known. Rogation Sunday (1864)Rogation Sunday-the fifth after Easter- is one of the moveable festivals of the Anglican Church. It derived its name from the Gospel for the day, teaching us how we may ask of God so as to obtain. In former times there was a perambulation, in the course of which, at certain spots, thanksgiving psalms were sung. FRANCOIS DE PARISIn the history of the great Jansenist schism which troubled the church in France for a hundred years, the name of the Deacon Francois de Paris bears a conspicuous place, not on account of anything he did or said in his life, but what happened regarding him after his death. Dying at thirty-seven, with a great reputation for sanctity and an infinite number of charitable works among the poor, his tomb in the cemetery of St. Medard came to be regarded with much veneration among such of the Parisian populace as had contracted any sympathies for Jansenism. Within about four years of his interment, this tomb was the daily resort of multitudes, who considered it a good place for their extra devotions. It then began to be rumoured that, among such of these individuals as were diseased, miraculous cures took place at the tomb of Paris. The French capital chanced to be then in want of a new sensation. The strange tales of the doings in the cemetery of St. Medard came very opportunely. It became a fashionable amusement to go there and witness the revivals of health which took place at the Deacon Paris's tomb. Scores of people afflicted with deep-seated rheumatism, sciatica, and contractions of the limbs, or with epilepsy and neuralgia, went away professing to have been suddenly and entirely cured in consequence of their devotions at the shrine of this quasi-Protestant saint. The Jesuits were of course scornfully incredulous of miracles wrought at an opposite shop. But nevertheless the cures went on, and all Paris was excited. In the autumn of 1731, the phenomena began to put on an even more striking shape. The votaries, when laid on the deacon's tomb, which was one slightly raised above the ground, began to experience strange convulsive movements, accompanied by dreadful pains, but always ending in cure. Some of them would be suddenly shot up several feet into the air, as by some explosive force applied below. Demonstrations of eloquence beyond the natural acquirements of the individual, knowledge of things beyond the natural scope of the faculties, powers of physical endurance above what seem to belong to human nature-in short, many of the phenomena alleged to happen in our own time under the influence of mesmerism-began to be exhibited by the convulsionaires. The scenes then daily presented in the St. Medard churchyard became a scandal too great to be endured by the opponents of the Jansenism, and a royal decree was issued, shutting up the place except for its ordinary business of receiving the bodies of the dead. As the Parisian epigram went-for on what subject will not the gay ones of such a city make jokes? De par le roi, defense a Dieu De faire miracle en ce lieu. This prohibition, however, was only attended with the effect of shifting the scenes of the alleged miracles. The convulsionaires continued to meet in private, and it was found that a few particles of earth from the grave of Paris sufficed to produce all the usual phenomena. For years there continued to be assemblages of people who, under the professed influence of the deacon's miraculous power, could sustain enormous weights on their bellies, and undergo other tortures, such as human beings usually shrink from with terror. The Jesuits, unable to deny the facts, or account for them on natural grounds, could only attribute them to the devil and other evil spirits. A gentleman of the name of Montgeron, originally sceptical, afterwards made a believer, employed himself for many years in collecting fully certified proofs of the St. Medard cures and other phenomena. He published three large volumes of these evidences, forming one of the most curious books in existence; bearing with patience several imprisonments in the Bastile as the punishment of his interference. There is no doubt of the sincerity of Montgeron. It cannot be disputed that few of the events of history are nearly so well evidenced as the convulsionaire phenomena. All that science can now say upon the subject is that the alleged facts are impossible, and therefore the evidence goes for nothing. MAY DAYThe outbreak into beauty which Nature makes at the end of April and beginning of May excites so joyful and admiring a feeling in the human breast, that there is no wonder the event should have at all times been celebrated in some way. The first emotion is a desire to seize some part of that profusion of flower and blossom which spreads around us, to set it up in decorative fashion, pay it a sort of homage, and let the pleasure it excites find expression in dance and song. A mad happiness goes abroad over the earth, that Nature, long dead and cold, lives and smiles again. Doubtless there is mingled with this, too, in bosoms of any reflection, a grateful sense of the Divine goodness, which makes the promise of seasons so stable and so sure. Amongst the Romans, the feeling of the time found vent in their Floralia, or Floral Games, which began on the 28th of April, and lasted a few days. Nations taking more or less their origin from Rome have settled upon the 1st of May as the special time for fetes of the same kind. With ancients and moderns alike it was one instinctive rush to the fields, to revel in the bloom which was newly presented on the meadows and the trees; the more city-pent the population, the more eager apparently the desire to get among the flowers, and bring away samples of them; the more sordidly drudging the life, the more hearty the relish for this one day of communion with things pure and beautiful. Among the barbarous Celtic populations of Europe, there was a heathen festival on the same day, but it does not seem to have been connected with flowers. It was called Beltein, and found expression in the kindling of fires on hill tops by night. Amongst the peasantry of Ireland, of the Isle of Man, and of the Scottish Highlands, such doings were kept up till within the recollection of living people. We can see no identity of character in the two festivals; but the subject is an obscure one, and we must not speak on this point with too much confidence. In England we have to go back several generations to find the observances of May-day in their fullest development. In the sixteenth century it was still customary for the middle and humbler classes to go forth at an early hour of the morning, in order to gather flowers and hawthorn branches, which they brought home about sunrise, with accompaniments of horn and tabor, and all possible signs of; joy and merriment. With these spoils they would decorate every door and window in the village. By a natural transition of ideas, they gave to the hawthorn bloom the name of the May; they called this ceremony 'the bringing home the May;' they spoke of the expedition to the woods as 'going a-Maying.' The fairest maid of the village was crowned with flowers, as the 'Queen of the May;' the lads and lasses met, danced and sang together, with a freedom which we would fain think of as bespeaking comparative innocence as well as simplicity. In a somewhat earlier age, ladies and gentlemen were accustomed to join in the Maying festivities. Even the king and queen condescended to mingle on this occasion with their subjects. In Chaucer's Court of Love, we read that early on May-day 'Forth goeth all the court, both most and least, to fetch the flowers fresh.' And we know, as one illustrative fact, that, in the reign of Henry VIII the heads of the corporation of London went out into the high grounds of Kent to gather the May, the king and his queen, Catherine of Arragon, coming from their palace of Greenwich, and meeting these respected dignitaries on Shooter's Hill. Such festal doings we cannot look back upon without a regret that they are no more. They give us the notion that our ancestors, while wanting many advantages which. an advanced civilization has given to us, were freer from monotonous drudgeries, and more open to pleasurable impressions from outward nature. They seem somehow to have been more ready than we to allow themselves to be happy, and to have often been merrier upon little than we can be upon much. The contemporary poets are full of joyous references to the May festivities. How fresh and sparkling is Spenser's description of the going out for the May: Siker this morrow, no longer ago, I saw a shole of shepherds outgo With singing, and shouting, and jolly cheer; Before them yode a lusty Tabrere, That to the many a horn-pipe play'd, Where to they dance each one with his maid. To see these folks make such jouissance, Made my heart after the pipe to dance. Then to the greenwood they speeden them all, To fetchen home May with their musical: And home they bring him in a royal throne Crowned as king; and his queen attone Was Lady Flora, on whom did attend A fair flock of fairies, and a fresh bend Of lovely nymphs-0 that I were there To helpen the ladies their May-bush to bear! Herrick, of course, could never have overlooked a custom so full of a living poetry. 'Come, my Corinna,' says he, ------- Come, and coming mark flow each field turns a street, and each street a park, Made green and trimmed with trees: see how Devotion gives each house a bough Or branch; each porch, each door, ere this An ark, a tabernacle is Made up of white-thorn neatly interwove. A deal of youth ere this is come Back, and with white-thorn laden home. Some have dispatched their cakes and cream, Before that we have left to dream Not content with a garlanding of their brows, of their doors and windows, these merry people of the old days had in every town, or considerable district of a town, and in every village, a fixed pole, as high as the mast of a vessel of a hundred tons, on which each May morning they suspended wreaths of flowers, and round which. they danced in rings pretty nearly the whole day.  The May-pole, as it was called, had its place equally with the parish church or the parish stocks; or, if anywhere one was wanting, the people selected a suitable tree, fashioned it, brought it in triumphantly, and erected it in the proper place, there from year to year to remain. The Puritans-those most respectable people, always so unpleasantly shown as the enemies of mirth and good humour-caused May-poles to be uprooted, and a stop put to all their jollities; but after the Restoration they rites re-commenced. Now, alas! in the course of were everywhere re-erected, and the appropriate the mere gradual change of manners, the May-pole has again vanished. They must now be pretty old people who remember ever seeing one. Washington Irving, who visited England early in this century, records in his Sketch Book, that he had seen one: I shall never,' he says, 'forget the delight I felt on first seeing a May-pole. It was on the banks of the Dee, close by the picturesque old bridge that stretches across the river from the quaint little city of Chester. I had already been carried back into former days by the antiquities of that venerable place, the examination of which is equal to turning over the pages of a black-letter volume, or gazing on the pictures in Froissart. The May-pole on the margin of that poetic stream completed the illusion. My fancy adorned it with wreaths of flowers, and peopled the green bank with all the dancing revelry of May-day. The mere sight of this May-pole gave a glow to my feelings, and spread a charm over the country for the rest of the day; and as I traversed a part of the fair plains of Cheshire, and the beautiful borders of Wales, and looked from among swelling hills down a long green valley, through which 'the Deva wound its wizard stream,' my imagination turned all into a perfect Arcadia. I value every custom that tends to infuse poetical feeling into the common people, and to sweeten and soften the rudeness of rustic manners, without destroying their simplicity. Indeed, it is to the decline of this happy simplicity that the decline of this custom may be traced; and the rural dance on the green, and the homely May-day pageant, have gradually disappeared, in proportion as the peasantry have become expensive and artificial in their pleasures, and too knowing for simple enjoyment. Some attempts, indeed, have been made of late years by men of both taste and learning to rally back the popular feeling to these standards of primitive simplicity; but the time has gone by-the feeling has become chilled by habits of gain and traffic --the country apes the manners and amusements of the town, and little is heard of May-day at present, except from the lamentations of authors, who sigh after it from among the brick walls of the city.' The custom of having a Queen of the May, or May Queen, looks like a relic of the heathen celebration of the day: this flower-crowned maid appears as a living representative of the goddess Flora, whom the Romans worshipped on this day. Be it observed, the May Queen did not join in the revelries of her subjects. She was placed in a sort of bower or arbour, near the May-pole, there to sit in pretty state, an object of admiration to the whole village. She herself was half covered with flowers, and her shrine was wholly composed of them. It must have been rather a dull office, but doubtless to the female heart had its compensations. In our country, the enthronization of the May Queen has been longer obsolete than even the May-pole; but it will be found that the custom still survives in France. The only relic of the custom now surviving is to be found among the children of a few out-lying places, who, on May-day, go about with a finely-dressed doll, which they call the Lady of the May, and with a few small semblances of May-poles, modestly presenting these objects to the gentlefolks they meet, as a claim for halfpence, to be employed in purchasing sweetmeats. Our artist has given a very pretty picture of this infantine representation of the ancient festival.  In London there are, and have long been, a few forms of May-day festivity in a great measure peculiar. The day is still marked by a celebration, well known to every resident in the metropolis, in which the chimney-sweeps play the sole part. What we usually see is a small band, composed of two or three men in fantastic dresses, one smartly dressed female glittering with spangles, and a strange figure called Jack-in-the-green, being a man concealed within a tall frame of herbs and flowers, decorated with a flag at top. All of these figures or persons stop here and there in the course of their rounds, and dance to the music of a drum and fife, expecting of course to be remunerated by halfpence from the onlookers. It is now generally a rather poor show, and does not attract much regard; but many persons who have a love for old sports and day-observances, can never see the little troop without a feeling of interest, or allow it to pass without a silver remembrance. How this black profession should have been the last sustainers of the old rites of May-day in the metropolis does not appear.  At no very remote time-certainly within the present century-there was a somewhat similar demonstration from the milk-maids. In the course of the morning the eyes of the house-holders would be greeted with the sight of a milch-cow, all garlanded with flowers, led along by a small group of dairy-women, who, in light and fantastic dresses, and with heads wreathed in flowers, would dance around the animal to the sound of a violin or clarinet. At an earlier time, there was a curious addition to this choral troop, in the form of a man bearing a frame which covered the whole upper half of his person, on which were hung a cluster of silver flagons and dishes, each set in a bed of flowers. With this extraordinary burden, the legs, which alone were seen, would join in the dance,-rather clumsily, as might be expected, but much to the mirth of the spectators,-while the strange pile above floated and flaunted about with an air of heavy decorum, that added not a little to the general amusement. We are introduced to the prose of this old custom, when we are informed that the silver articles were regularly lent out for the purpose at so much an hour by pawn-brokers, and that one set would serve for a succession of groups of milk-maids during the day. In Vauxhall, there used to be a picture representing the May-day dance of the London milk-maids: from an engraving of it the accompanying cut is taken. It will be observed that the scene includes one or two chimney-sweeps as side figures. In Scotland there are few relics of the old May-day observances--we might rather say none, beyond a lingering propensity in the young of the female sex to go out at an early hour, and wash their faces with dew. At Edinburgh this custom is kept up with considerable vigour, the favourite scene of the lavation being Arthur's Seat. On a fine May morning, the appearance of so many gay groups perambulating the hill sides and the intermediate valleys, searching for dew, and rousing the echoes with their harmless mirth, has an indescribably cheerful effect. The fond imaginings which we entertain regarding the 1st of May-alas! so often disappointed-are beautifully embodied in a short Latin lyric of George Buchanan, which the late Archdeacon Wrangham thus rendered in English: THE FIRST OF MAY Hail! sacred thou to sacred joy, To mirth and wine, sweet first of May! To sports, which no grave cares alloy, The sprightly dance, the festive play! Hail! thou of ever circling time, That gracest still the ceaseless flow! Bright blossom of the season's prime Age, hastening on to winter's snow! When first young Spring his angel face On earth unveiled, and years of gold Gilt with pure ray man's guileless race, By law's stern terrors uncontrolled: Such was the soft and genial breeze, Mild Zephyr breathed on all around; With grateful glee, to airs like these Yielded its wealth th' unlaboured ground. So fresh, so fragrant is the gale, Which o'er thc islands of the blest Sweeps; where nor aches the limbs assail, Nor age's peevish pains infest. Where thy hushed groves, Elysium, sleep, Such winds with whispered murmurs blow; So where dull Lethe's waters creep, They heave, scarce heave the cypress-bough. And such when heaven, with penal flame, Shall purge the globe, that golden day Restoring, o'er man's brightened frame Haply such gale again shall play. Hail, thou, the fleet year's pride and prime! Hail! day which Fame should bid to bloom! Hail! image of primeval time! Hail! sample of a world to come! MAY-POLES: ENGLISH AND FOREIGNOne of the London parishes takes its distinctive name from the May-pole which in olden times overtopped its steeple. The parish is that of St. Andrew Undershaft, and its May-pole is celebrated by the father of English poetry, Geoffry Chaucer, who speaks of an empty braggart:-- Right well aloft, and high ye beare your head, As ye would beare the great shaft of Cornhill. Stow, who is buried in this church, tells us that in his time the shaft was set up 'every year, on May-day in the morning,' by the exulting Londoners, 'in the midst of the street before the south door of the said church; which shaft, when it was set on end, and fixed in the ground, was higher than the church steeple.' During the rest of the year this pole was hung upon iron hooks above the doors of the neighbouring houses, and immediately beneath the projecting penthouses which kept the rain from their doors. It was destroyed in a fit of Puritanism in the third year of Edward VI, after a sermon preached at St. Paul's Cross against May games, when the inhabitants of these houses 'sawed it in pieces, everie man taking for his share as much as had layne over his doore and stall, the length of his house, and they of the alley divided amongst them so much as had lain over their alley gate.' The earliest representation of an English May-pole is that published in the variorum Shakspeare, and depicted on a window at Betley, in Staffordshire, then the property of Mr. Tollett, and which he was disposed to think as old as the time of Henry VIII. The pole is planted in a mound of earth, and has affixed to it St. George's reel-cross banner, and a white pennon or streamer with a forked end. The shaft of the pole is painted in a diagonal line of black colour, upon a yellow ground, a characteristic decoration of all these ancient May-poles, as alluded to by Shakspeare in his Midsummer Night's Dream, where it gives point to Hermia's allusion to her rival Helena as a 'painted May-pole.' The fifth volume of Halliwell's folio edition of Shakspeare has a curious coloured frontispiece of a May-pole, painted in continuous vertical stripes of white, red, and blue, which stands in the centre of the village of Welford, in Gloucestershire, about five miles from Stratford-on-Avon. It may be an exact copy and legitimate successor of one standing there in the days when the bard himself visited the village. It is of great height, and is planted in the centre of a raised mound, to which there is an ascent by three stone steps: on this mound probably the dancers performed their gyrations. Stubbes, in his Anatomie of Abuses, 1584, speaks of May-poles 'covered all over with flowers and hearbes, bounde rounde aboute with stringes, from the top to the bottom, and some tyme painted with variable colours.' The London citizen, Machyn, in his Diary, 1552, tells of one brought at that time into the parish of Fenchurch; 'a goodly May-pole as you have seene; it was painted Whyte and green.' In the illuminations which decorate the manuscript 'Hours' once used by Anne of Brittany and now preserved in the Bibliotheque Royale at Paris, and which are believed to have been painted about 1499, the month of May is illustrated by figures bearing flower-garlands, and behind them the curious May-pole here copied,which is also decorated by colours on the shaft, and ornamented by garlands arranged on hoops, from which hang small gilded pendents. The pole is planted on a triple grass-covered mound, embanked and strengthened by timber-work. That this custom of painting and decorating the May-pole was very general until a comparatively recent period, is easy of proof. A Dutch picture, bearing date 1625, furnishes our third specimen; here the pole is surmounted by a flower-pot containing a tree, stuck all round with gaily-coloured flags; three hoops with garlands are suspended below it, from which hang gilded balls, after the fashion of the pendent decorations of the older French example. The shaft of the pole is painted white and blue. London boasted several May-poles before the days of Puritanism. Many parishes vied with each other in the height and adornment of their own. One famed pole stood in Basing-lane, near St. Paul's Cathedral, and was in the time of Stow kept in the hostelry called Gerard's Hall. 'In the high-roofed hall of this house,' says he, 'sometime stood a large fir pole, which reached to the roof thereof,-a pole of forty feet long, and fifteen inches about, fabled to be the justing staff of Gerard the Giant.' A carved wooden figure of this giant, pole in hand, stood over the gate of this old inn, until March 1852, when the whole building was demolished for city improvements. The most renowned London May-pole, and the latest in existence, was that erected in the Strand, immediately after the Restoration. Its history is altogether curious. The Parliament of 1644 had ordained that 'all and singular May-poles that are or shall be erected, shall be taken down,' and had enforced their decree by penalties that effectually carried out their gloomy desires. When the populace gave again vent to their May-day jollity in 1661, they determined on planting the tallest of these poles in the most conspicuous part of the Strand, bringing it in triumph, with drums beating, flags flying, and music playing, from Scotland Yard to the opening of Little Drury Lane, opposite Somerset House, where it was erected, and which lane was after termed 'May-pole Alley' in consequence. 'That stately cedar erected in the Strand, 134 feet high,' as it is glowingly termed by a contemporary author, was considered as a type of 'golden days' about to return with the Stuarts. It was raised by seamen, expressly sent for the purpose by the Duke of York, and decorated with three gilt crowns and other enrichments. It is frequently alluded to by authors. Pope wrote-- Where the tall May-pole once o'erlooked the Strand. Our cut, exhibiting its features a short while before its demolition, is a portion of a long print by Vertue representing the procession of the members of both Houses of Parliament to St. Paul's Cathedral to render thanks for the Peace of Utrecht, July 7th, 1713. On this occasion the London charity children were ranged on scaffolds, erected on the north side of the Strand, and the cut represents a portion of one of these scaffolds, terminating at the opening to Little Drury Lane, and including the pole, which is surmounted by a globe, and has a long streamer floating beneath it. Four years after-wards, this famed pole, having grown old and decayed, was taken down. Sir Isaac Newton arranged for its purchase with the parish, and it was carried to Wanstead, in Essex, and used as a support to the great telescope (124 feet in length), which had been presented to the Royal Society by the French astronomer, M. Hugon. Its celebrity rendered its memory to be popularly preserved longer than falls to the lot of such relics of old London, and an anonymous author, in the year 1800, humorously asks:-- What's not destroy'd by Time's relentless hand? Where's Troy?-and where's the May-pole in the Strand? Scattered in some of the more remote English villages are a few of the old May-poles. One still does duty as the supporter of a weathercock in the churchyard at Pendleton, Manchester; others might be cited, serving more ignoble uses than they were originally intended for. The custom of dressing them with May garlands, and dancing around them, has departed from utilitarian England, and the jollity of old country customs given way to the ceaseless labouring monotony of commercial town life. The same thing occurs abroad as at home, except in lonely districts as yet unbroken by railways, and our concluding illustration is derived from such a locality. Between Munich and Salzburg are many quiet villages, each rejoicing in its May-pole; that we have selected for engraving is in the middle of the little village of St. Egydien, near Salzburg. It is encircled by garlands, and crowned with a May-bush and flags. Beneath the garlands are figures dressed in the ordinary peasant costume, as if ascending the pole; they are large wooden dolls, dressed in linen and cloth clothing, and nailed by hands and knees to the pole. It is the custom here to place such figures, as well as birds, stags, &c., up the poles. In one instance a stag-hunt is so represented. The pole thus decorated remains to adorn the village green, until a renovation of these decorations takes place on the yearly May festival. MAY, AS CELEBRATED IN OLD ENGLISH POETRYOur mediaeval forefathers seem to have cherished a deep admiration for nature in all her forms; they loved the beauty of her flowers, and the song of her birds, and, whenever they could, they made their dwellings among her most picturesque and pleasant scenery. May was their favourite month in the year, not only because it was the time at which all nature seemed to spring into new life, but because a host of superstitions, dating from remote antiquity, were attached to it, and had given rise to many popular festivals and observances. The poets especially loved to dwell on the charms of the month of May. 'In the season of April and May,' says the minstrel who sang the history of the Fitz-Warines, 'when fields and plants become green again, and everything living recovers virtue, beauty, and force, hills and vales resound with the sweet songs of birds, and the hearts of all people, for the beauty of the weather and the season, rise up and gladden themselves.' The month of May is celebrated in the earliest attempts at English lyric poetry (Wright's Specimens of Lyric Poetry of the Reign of Edward 1, p. 45), as the season when 'it is pleasant at daybreak,'-- 'In May hit murgeth when hit dawes;' and 'Blosmes bredeth on the bowes.' The 'Romance of Kyng Alisaunder,' as old, apparently, as the beginning of the fourteenth century, similarly speaks of the pleasantness of May (for it must be kept in mind that the old meaning of the word merry was pleasant)-- Mery time it is in May; The foules syngeth her lay; The knighttes loveth the tornay; Maydens so dauncen and thay play. And the same poet alludes in another place (1. 2,547) to the melody of the birds-- In tyme of May, the nyghtyngale In wode makith miry gale (pleasant melody); So doth the foules grete and smale, Som on hulle, som on dale. Much in the same tone is the 'merry' month celebrated in the celebrated 'Romance of the Rose,' which we will quote in the translation made by our own poet Chaucer. After alluding to the pleasure and joy which seemed to pervade all nature, after its recovery from the rigours of winter, now that May had brought in the summer season, the poet goes on to say that-- -than bycometh the ground so proude, That it wole have a newe shroude, And makith so quaynt his robe and faire, That it had hewes an hundred payre Of gras and flouris, ynde (blue) and pers (grey), And many hewes ful dyvers: That is the robe I mene, iwis (truly), Through which the ground to preisen is. The briddes, that haven lefte her song, While thei han suffrid cold so strong In weeres gryl and derk to sight, Ben in May for the sonne bright So glade, that they shewe in syngyng That in her hertis is such lykyng ( pleasure), That they mote syngen and be light. Than doth the nyghtyngale hir myght To make noyse and syngen blythe, Than is blisful many sithe (times) The chelaundre (goldfinch) and the papyngay Than young folk entenden ay For to ben gay and amorous; The tyme is than so saverous. Hard is his hart that loveth nought In May, whan al this mirth is wrought; Whan he may on these braunches here The smale briddes syngen clere. The whole spirit of the poetry of mediaeval England is embodied in the writings of Chaucer, and it is no wonder if we often find him singing the praises of May. The daisy, in Chaucer's estimate, was the prettiest flower in that engaging month- How have I thanne suche a condition, That of al the floures in the mede Thanne love I most these floures white and redo, Suche as men callen daysyes in our tonne. To hem have I so grete affeccioun, As I seyde erst, whanne comen is the May, That in my bed ther daweth (dawns) me no day That I nam (am not) uppe and walkyng in the merle, To seen this floure ayein (against) the sunne sprede Whan it up-ryseth erly by the morwe; That blisful sight softeneth al my sorwe. Chaucer more than once introduces the feathered minstrels welcoming and worshipping the month of May; as, for an instance, in his 'Court of Love,' where robin redbreast is introduced at the 'lectern,' chaunting his devotions-- 'Hail now,' quoth he, 'o fresh sason of May, Our moneth glad that singen on the spray! Hail to the floures, red, and white, and blewe, Which by their vertue maketh our lust newe I' And so again in 'The Cuckow and the Nightingale,' when the poet sought the fields and groves on a May morning- There sat I downe among the faire floures, And sawe the birdes trippe out of hir boures, There as they rested hem alle the night; They were so joyful of the dayes light, They gan of May for to done honoures. It is the season which puts in motion people's hearts and spirits, and makes them active with life. 'For,' as we are told in the same poem- -every true gentle herte free, That with him is, or thinketh for to be, Againe May now shal have some stering (stirring) Or to joye, or elles to some mourning, In no season so muche, as thinketh me. For whan they may here the birdes singe, And see the floures and the leaves springe, That bringeth into hertes remembraunce A manner ease, medled (mixed) with grevaunce, And lustie thoughtes full of grete longinge. May, in fact, was the season which was to last for ever in heaven, according to the idea expressed in the inscription on the gate of Chaucer's happy 'park'-- Through me men gon into the blisful place Of hertes, hele and dedly, woundes cure; Through me men gon into the welle of grace, There grene and lusty May shal ever endure. In the 'Court of Love,' when the birds have concluded their devotional service in honour of the month, they separate to gather flowers and branches, and weave them into garlands-- Thus sange they alle the service of the feste, And that was done right early, to my dome (as I judged); And forth goeth al the court, both moste and leste, To feche the floures freshe, and braunche, and biome; And namely (especially) hawthorn brought both page and grome, With freshe garlandes party blew and white; And than rejoysen in their grete delight, Eek eche at other threw the floures bright, The primerose, the violete, and the gold' (the marigold). The practice of going into the woods to gather flowers and green boughs, and make them into garlands on May morning, is hardly yet quite obsolete, and it is often mentioned by the other old poets, as well as by Chaucer. At the period when we learn more of the domestic manners of our kings and queens, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, we find even royalty following the same custom, and rambling in the fields and woods at daybreak to fetch home 'the May.' So in Chaucer's 'Knightes Tale,' it was on a May morning that- Arcite, that is in the court ryal With Theseus, his squyer principal, Is risen, and loketh on the mery day. And for to doon his observance to May, Remembryng of the poynt of his desire, He on his courser, stertyng as the fire, Is riden into feeldes him to pleye, Out of the court, were it a mile or tweye. And to the grove, of which that I yow tolde, By aventure his wey he gan to holde, To make him a garland of the greves, Were it of woodewynde or hawthorn leves; And lowde he song agens the sonne scheene. MAY-DAY CAROLTwo or three years ago we obtained the following song or carol from the mouths of several parties of little girls in the parish of Debden, in Essex, who on May morning go about from house to house, carrying garlands of different sizes, some large, with a doll dressed in white in the middle, which no doubt represents what was once the Virgin Mary. All who sing it, do so with various readings, or rather with corruptions, and it was only by comparing a certain number of these different versions, that we could make it out as intelligible as it appears in this text: I, been a rambling all this night, And sometime of this day; And now returning back again, I brought you a garland gay. A garland gay I brought you here, And at your door I stand; 'Tis nothing but a sprout, but 'tis well budded out, The works of our Lord's hand. So dear, so dear as Christ lov'd us, And for our sins was slain, Christ bids us turn from wickedness, And turn to the Lord again. Sometimes a sort of refrain is sung after each verse, in the following words: Why don't you do as we have done, The very first day of May; And from my parents I have come, And would no longer stay. This is evidently a very old ballad, dating probably from as far back as the time of Elizabeth, when, according to the puritanical moralists, it was the custom for the youths of both sexes to go into the fields and woods on May eve, and remain out all night, returning early in the morning with green branches and garlands of flowers. The doll representing the Virgin Mary perhaps refers us back to a still older period. The puritans have evidently left their mark upon it, and their influence is still more visible in a longer version of it, preserved in a neighbouring parish, that of Hitchin, in Hertfordshire, which was communicated to Hone's Every Day Book, as sung in 1823 by the men in that parish. This also was, we believe, the case a few years ago in Debenham parish, where the girls have only taken it up at a comparatively recent period. The following is the Hitchin version: Remember us poor Mayers all, And thus we do begin To lead our lives in righteousness, Or else we die in sin. We have been rambling all this night, And almost all this day, And now returned back again, We have brought you a branch of May. A branch of May we have brought you, And at your door it stands; It is but a sprout, but it's well budded out By the work of our Lord's hands. The hedges and trees they are so green, As green as any leek, Our Heavenly Father he watered them With heavenly dew so sweet. The heavenly gates are open wide, Our paths are beaten plain, And, if a man be not too far gone, He may return again. The life of man is but a span, It flourishes like a flower; We are here to-day, and gone to-morrow, And we are dead in one hour. The moon shines bright, and the stars give a light, A little before it is day; So God bless you all, both great and small, And send you a joyful May! The same song is sung in some other parishes in the neighbourhood of Debenham, with further variations, which show us, in a curious and interesting manner, the changes which such popular records undergo in passing from one generation to another. At Thaxted, the girls wave branches before the doors of the inhabit-ants, but they seem to have forgotten the song altogether. MAY-DAY FESTIVITIES IN FRANCEIn some parts of France, before the Revolution, it was customary to celebrate the arrival of May-day by exhibitions, in which the successors of William of Guienne and Abelard contended for the golden violet. The origin of these miniature Olympics is traced back to the year 1323, when seven persons of rank invited all the troubadours of Provence to assemble at Toulouse the first of May of the year following. Verses were then recited; and amidst much glee, excitement, and enthusiasm, Arnauld Vidal de Castelraudari, co-temporary with Deguileville and Jean de Meung, bore off the first prize.  Every succeeding year was accompanied by similar competitions, and so profitable did the large concourse of people from the neighbouring countries become to the good burgesses of Toulouse, that at a later period, the 'Jeux Floraux,' as they were called, were conducted at their expense, and the prizes provided by the coffers of the city. In 1540, Clemente Isaure, a lady of rank, and a patroness of the belles lettres, bequeathed the great bulk of her fortune for the purpose of perpetuating this custom, by providing golden and silver flowers of different design and value as rewards for the successful. It may be imagined with what enthusiasm the French people attended these lively meetings, where the gay sons of the South repeated their glowing praises of love, beauty, and knightly worth, in the soft numbers of the langue d'oc. It may not be uninteresting that, in 1694, 'les Jeux Floraux' were continued by order of the Grand Monarque, when forty members (being the same number as that of the Academie Francaise) were elected into an academy for the purpose of having the fetes conducted with more splendour and regularity. The academicians' office was to preside at the feasts, decide who were the victors, and distribute the rewards. When I was quite a child, I went with my mother to visit her relatives at a small town in the South of France. We arrived about the end of April, when the spring had fully burst forth, with its deep blue sky, its balmy air, its grassy meadows, its flowering hedges and trees already green. One morning I went out with my mother to call upon a friend: when we had taken a few steps, she said: 'To-day is the first of May; if the customs of my childhood are still preserved here, we shall see some 'Mays' on our road.' 'Mays,' I said, repeating a word I heard for the first time, ' what are they?' My mother replied by pointing to the opposite side of the place we were crossing: ' top, look there,' she said; 'that is a May.' Under the gothic arch of an old church porch a narrow step was raised covered with palms. A living being, or a statue-I could not discern at the distance-dressed in a white robe, crowned with flowers, was seated upon it; in her right hand she held a leafy branch; a canopy above her head was formed of garlands of box, and ample draperies which fell on each side encircled her in their snowy folds. No doubt the novelty of the sight caused my childish imagination much surprise, my eyes were captivated, and I scarcely listened to my mother, who gave me her ideas on this local custom; ideas, the simple and sweet poetry of which I prefer to accept instead of discussing their original value. 'Because the month of May is the month of spring,' said she, 'the month of flowers, the month consecrated to the Virgin, the young girls of each quartier unite to celebrate its return. They choose a pretty child, and dress her as you see; they seat her on a throne of foliage, they crown her and make her a sort of goddess; she is May, the Virgin of May, the Virgin of lovely days, flowers, and green branches. See, they beg of the passers-by, saying, ' For the May.' People give, and their offerings will be used some of these days for a joyous festival.' When we came near, I recognised in the May a lovely little girl I had played with the previous day. At a distance I thought she was a statue. Even close at hand the illusion was still possible; she seemed to me like a goddess on her pedestal, who neither distinguished nor recognised the profane crowd passing beneath her feet. Her only care was to wear a serene aspect under her crown of periwinkle and narcissus, laying her hand on her olive sceptre. She had, it is true, a gracious smile on her lips, a sweet expression in her eyes; but these, though charming all, did not seem to seek or speak to any in particular; they served as an adornment to her motionless physiognomy, lending life to the statue, but neither voice nor affections. Was it coquetry in so young a child thus studying to gain admiration? I know not, but to this day I can only think of the enchantment I felt in contemplating her. An older sister of hers came forward as a collector, saying, 'For the May.' My mother stopped, and drawing some money from her purse, laid it on the china saucer that was presented; as for myself, I took a handful of sous, all that I could find in my pocket, and gave them with transport; I was too young to appreciate the value of my gift, but I felt the exquisite pleasure of giving. In passing through the town we met with several other 'Mays,' pretty little girls, perhaps, but not understanding their part; always rest-less, arranging their veils, touching their crowns, talking, eating sweetmeats, or weary, stiff, half asleep, with an awkward, unpleasing attitude. None was the May, the representative of the joyous season of sweet and lovely flowers, but my first little friend. [That there was a ceremony resembling this in England long ago has already been mentioned. It is thus adverted to by Browne, in Britannia's Pastorals- As I have seene the Lady of the May Set in an harbour -- - - Built by the May-pole, where the jocund swains Dance with the maidens to the bagpipe's straines, When envious night commands them to be gone, Call for the merry yongsters one by one, And for their well performance some disposes, To this a garland interwove with roses To that a carved hooke, or well wrought scrip; Gracing another with her cherry lip: To one her garter, to another then A handkerchiefe cast o're and o're again; And none returneth empty, that hath spent His paynes to fill their rurall merriment. ROBIN HOOD GAMESMingling with the festivities of May-day, there was a distinct set of sports, in great vogue in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, meant to represent the adventures of the legendary Robin Hood. They have been described with (it is believed) historical fidelity in Mr. Strutt's novel of Queen Hoo Hall, where the author has occasion to introduce them as performed by the dependents and servants of an English baron. (We abridge a little in the matter of costume.) In the front of the pavilion, a large square was staked out, and fenced with ropes, to prevent the crowd from pressing upon the performers, and interrupting the diversion; there were also two bars at the bottom of the enclosure, through which the actors might pass and repass, as occasion required. Six young men first entered the square, clothed in jerkins of leather, with axes upon their shoulders like woodmen, and their heads bound with large garlands of ivy leaves, intertwined with sprigs of hawthorn. Then followed six young maidens of the village, dressed in blue kirtles, with garlands of prim-roses on their heads, leading a fine sleek cow decorated with ribbons of various colours interspersed with flowers; and the horns of the animal were tipped with gold. These were succeeded by six foresters equipped in green tunics, with hoods and hosen of the same colour; each of them carried a bugle-horn attached to a baldrick of silk, which he sounded as he passed the barrier. After them came Peter Lanaret, the baron's chief falconer, who personified Robin Hood; he was attired in a bright grass-green tunic, fringed with gold; his hood and his hosen were parti-coloured, blue and white; he had a large garland of rose-buds on his head, a bow bent in his hand, a sheaf of arrows at his girdle, and a bugle-horn depending from a baldrick of light blue tarantine, embroidered with silver; he had also a sword and a dagger, the hilts of both being richly embossed with gold. Fabian, a page, as Little John, walked at his right hand; and Cecil Cellerman, the butler, as Will Stukely, at his left. These, with ten others of the jolly outlaw's attendants who followed, were habited in green garments, bearing their bows bent in their hands, and their arrows in their girdles. Then came two maidens, in orange-coloured kirtles with white court pies, strewing flowers, followed immediately by the Maid Marian, elegantly habited in a watchet-coloured tunic reaching to the ground, She was supported by two bride-maidens, in sky-coloured rochets girt with crimson girdles. After them came four other females in green courtpies, and garlands of violets and cowslips. Then Sampson, the smith, as Friar Tuck, carrying a huge quarter-staff on his shoulder; and Morris, the mole-taker, who represented Much, the miller's son, having a long pole with an inflated bladder attached to one end. And after them the May pole, drawn by eight fine oxen, decorated with scarfs, ribbons, and flowers of divers colours, and the tips of their horns were embellished with gold. The rear was closed by the hobby-horse and the dragon. When the May-pole was drawn into the square, the foresters sounded their horns, and the populace expressed their pleasure by shouting incessantly until it reached the place assigned for its elevation. During the time the ground was preparing for its reception, the barriers of the bottom of the enclosure were opened for the villagers to approach and adorn it with ribbons, garlands, and flowers, as their inclination prompted them. The pole being sufficiently onerated with finery, the square was cleared from such as had no part to perform in the pageant, and then it was elevated amidst the reiterated acclamations of the spectators. The woodmen and the milk-maidens danced around it according to the rustic fashion; the measure was played by Peretto Cheveritte, the baron's chief minstrel, on the bagpipes, accompanied with the pipe and tabor, performed by one of his associates. When the dance was finished, Gregory the jester, who undertook to play the hobby-horse, came forward with his appropriate equipment, and frisking up and down the square without restriction, imitated the galloping, curvetting, ambling, trotting, and other paces of a horse, to the in-finite satisfaction of the lower classes of the spectators. He was followed by Peter Parker, the baron's ranger, who personated a dragon, hissing, yelling, and shaking his wings with wonderful ingenuity; and to complete the mirth, Morris, in the character of Much, having small bells attached to his knees and elbows, capered here and there between the two monsters in the form of a dance; and as often as he came near to the sides of the enclosure, he cast slyly a handful of meal into the faces of the gaping rustics, or rapped them about their heads with the bladder tied at the end of his pole. In the meantime, Sampson, representing Friar Tuck, walked with much gravity around the square, and occasionally let fall his heavy staff upon the toes of such of the crowd as he thought were approaching more forward than they ought to do; and if the sufferers cried out from the sense of pain, he addressed them in a solemn tone of voice, advising them to count their beads, say a paternoster or two, and to beware of purgatory. These vagaries were highly palatable to the populace, who announced their delight by repeated plaudits and loud bursts of laughter; for this reason they were continued for a considerable length of time; but Gregory, beginning at last to falter in his paces, ordered the dragon to fall back. The well-nurtured beast, being out of breath, readily obeyed, and their two companions followed their example, which concluded this part of the pas-time. Then the archers set up a target at the lower part of the green, and made trial of their skill in a regular succession. Robin Hood and Will Stukely excelled their comrades, and both of them lodged an arrow in the centre circle of gold, so near to each other that the difference could not readily be decided, which occasioned them to shoot again, when Robin struck the gold a second time, and Stukely's arrow was affixed upon the edge of it. Robin was therefore adjudged the conqueror; and the prize of honour, a garland of laurel embellished with variegated ribbons, was put upon his head; and to Stukely was given a garland of ivy, because he was the second best performer in that contest. The pageant was finished with the archery, and the procession began to move away to make room for the villagers, who afterwards assembled in the square, and amused themselves by dancing round the May-pole in promiscuous companies, according to the ancient custom.' In Scotland, the Robin Hood games were enacted with great vivacity at various places, but particularly at Edinburgh; and in connection with them were the sports of the Abbot of Inobedience, or Unreason, a strange half serious burlesque on some of the ecclesiastical arrangements then prevalent, and also a representation called the Queen of May. A. recent historical work thus describes what took place at these whimsical merry-makings: At the approach of May, they (the people) assembled and chose some respectable individuals of their number-very grave and reverend citizens, perhaps-to act the parts of Robin Hood and Little John, of the Lord of Inobedience or the Abbot of Unreason, and 'make sports and jocosities' for them. If the chosen actors felt it inconsistent with their tastes, gravity, or engagements, to don a fantastic dress, caper and dance, and incite their neighbours to do the like, they could only be excused on paying a fine. On the appointed day, always a Sunday or holiday, the people assembled in their best attire and in military array, and marched in blithe procession to some neighbouring field, where the fitting preparations had been made for their amusement. Robin Hood and Little John robbed bishops, fought with pinners, and contended in archery among themselves, as they had done in reality two centuries before. The Abbot of Unreason kicked up his heels and played antics, like a modern pantaloon.' Maid Marian also appeared upon the scene, in flower-sprent kirtle, and with bow and arrows in hand, and doubtless slew hearts as she had formerly done harts. Mingling with the mad scene were the morris-dancers, with their fantastic dresses and jingling bells. So it was until the Reformation, when a sudden stop was put to the whole affair by severe penalties imposed by Act of Parliament. |