30th AprilBorn: Queen Mary II of England, 1662. Died: Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, Roman poet, 65, Rome; Chevalier Bayard, killed, 1524; John, Count de Tilly, military commander, 1632, Ingoldstadt; Dr. Robert Plot, naturalist, topographer, 1696, Borden; G. Farquhar, dramatist, 1707, London; Jean Jacques Barthelemi, 1795, Paris; Thomas Duncan, Scottish artist, 1845, Edinburgh; Samuel Maunder, author of books of information, 1849, London; Sir Henry Bishop, musical composer, 1855; James Montgomery, poet, 1854, Sheffield. Feast Day: St. Maximus, martyr, 251. Saints James, Marian, and others, martyrs in Numidia, 259. St. Sophia, virgin, martyr, 3rd century. St. Erkonwald, bishop of London, about 686. St. Adjutre, recluse, Vernon in Normandy, 1131. St. Catherine of Sienna, virgin, 1380. BAYARDThe compatibility of high warlike qualities with the gentlest nature is strikingly shown in the case of Bayard, who at once gave the hardest strokes in the battle and the tournament, and was in society the most amiable of men. Simple, modest, kindly, the delicate lover, the sincere friend, the frank cavalier, pious, humane, and liberal, nothing seems wanting to complete the character of the Chevalier sans peur et sans reproche. He ought to be the worship of all soldiers, for no one has done more to exalt the character of the profession. The exploits of Bayard fill the chronicles of his age, which embraces the whole reign of Louis XII, and the nine first years of that of Francis I. His end was characteristic. Engaged in the unfortunate campaign of Bonnivet, in Northern Italy, where the imperial army under the traitor De Bourbon pressed hard upon the retreating French troops, he was entreated to take the command and save the army if possible. 'It is too late,' he said; 'but my soul is God's, and my life is my country's.' Then putting himself at the head of a body of men-at-arms, he stayed the pressure of the enemy till struck in the reins by a ball, which brought him off his horse. He refused to retire, saying he never had shown his back to an enemy. He was placed against a tree, with his face to the advancing host. In the want of a cross, he kissed his sword; in the absence of a priest, he confessed to his maitred'hotel. He uttered consolations to his friends and servants. When De Bourbon came up, and expressed regret to see him in such a condition, he said, 'Weep for yourself, sir. For me, I have nothing to complain; I die in the course of my duty to my country. You triumph in betraying yours; but your successes are horrible, and the end will be sad.' The enemy honoured the remains of Bayard as much as his own countrymen could have done. FARQUHAR THE DRAMATIST AT LICHFIELDThis admirable comic writer appears, in other respects, to have been wedded to misfortune throughout his brief life. He was born at Londonderry in 1678, and educated in the University of Dublin. He appeared early at the Dublin theatre, made no great figure as an actor, and accidentally wounding a brother-comedian with a real sword, which he mistook for a foil, he forsook the stage, being then only seventeen years old. He accompanied the actor Wilks to London, and there attracted the notice of the Earl of Orrery, who gave him a commission in his own regiment. Wilks persuaded him to try his powers as a dramatist, and his first comedy, Love and a Bottle, produced in 1798, was very successful. In 1703, he adapted Beaumont and Fletcher's Wildgoose Chase, under the title of The Inconstant, which became popular. Young Mirabel in this play was one of Charles Kemble's most finished performances. Farquhar was married to a lady who deceived him as to her fortune; he fell into great difficulties, and was obliged to sell his commission; he sunk a victim to consumption and overexertion, and died, in his thirtieth year, leaving two helpless girls; one married 'a low tradesman,' the other became a servant, and the mother died in poverty. Our dramatist has laid the scene of two of his best comedies at Lichfield. He has drawn from his experience as a soldier the incidents of his Recruiting Officer, produced in 1706, and of his Beaux' Stratagem, written during his last illness. One of his recruiting scenes is a street at Lichfield, where Kite places one of his raw recruits to watch the motion of St. Mary's clock, and another the motion of St. Chad's. We all remember in the Beaux' Stratagem the eloquent jollity of Boniface upon his Lichfield 'Anno Domini 1706 ale.' 'The Dean's Walk' is the avenue described by Farquhar as leading to the house of Lady Bountiful, and in which Aimwell pretends to faint. The following amusing anecdote is also told of Farquhar at Lichfield. It was at the top of Market-street, that hastily entering a barber's shop, he desired to be shaved, which operation was immediately performed by a little deformed man, the supposed master of the shop. Dining the same day at the table of Sir Theophilus Biddulph, Farquhar was observed to look with particular earnestness at a gentleman who sat opposite to him; and taking an opportunity of following Sir Theophilus out of the room, he demanded an explanation of his conduct, as he deemed it an insult to be seated with such inferior company. Sir Theophilus, amazed at the charge, assured the captain the company were every one gentlemen, and his own particular friends. This, however, would not satisfy Farquhar; he was, he said, certain that the little humpbacked man who sat opposite to him at dinner was a barber, and had that very morning shaved him. Unable to convince the captain of the contrary, the baronet returned to the company, and stating the strange assertion of Farquhar, the mystery was elucidated, and the gentleman owned having, for joke's sake, as no other person was in the shop, performed the office of terror to the captain. SIR HENRY R. BISHOP'In every house where music, more especially vocal music, is welcome, the name of Bishop has long been, and must long remain, a household word. Who has not been soothed by the sweet melody of 'Blow, gentle gales;' charmed by the measures of 'Lo! here the gentle lark;' enlivened by the animated strains of ' Foresters, sound the cheerful horn;' touched by the sadder music of 'The winds whistle cold.' Who has not been haunted by the insinuating tones of 'Tell me, my heart;' 'Under the greenwood tree;' or, 'Where the wind blows,' which Rossini, the minstrel of the south, loved so well? Who has not felt sympathy with As it fell upon a day, In the merry month of May; admired that masterpiece of glee and chorus, 'The chough and crow;' or been moved to jollity at some convivial feast by 'Mynheer Van Dunck,' the most original and genial of comic glees?'-Contemporary Obituary Notice. THE QUARTER-STAFF

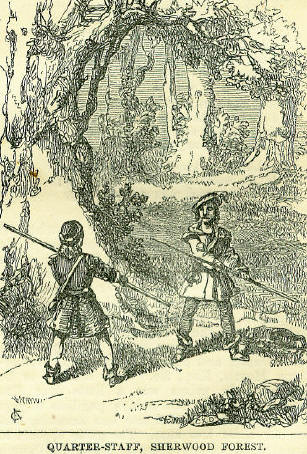

Contentions with the quarter-staff take their place among the old amusements of the people of England: rather rough for the taste of the present day, yet innocent in comparison with other sports of our forefathers. The weapon, if it be worthy of such a term-perhaps we should content ourselves with calling it implement--was a tough piece of wood, of about eight feet long, not of great weight, which the practitioner grasped in the middle with one hand, while with the other he kept a loose hold midway between the middle and one end. An adept in the use of the staff might be, to one less skilled, a formidable opponent. Dryden speaks of the use of the quarter-staff in a manner which would imply that in his time, when not in use, the weapon was hung upon the back, for he says His quarter-staff, which he could ne'er forsake, Hung half before and half behind his back. Bacon speaks of the use of cudgels by the captains of the Roman armies; but it is very questionable whether these cudgels partook of the character of the quarter-staff. Most persons will remember how often bouts at quarter-staff occur in the ballads descriptive of the adventures of Robin Hood and Little John. Thus, in the encounter of Robin with the tanner, Arthur - as Bland: Then Robin he unbuckled his belt, And laid down his bow so long; He took up a staff of another oak graff, That was both stiff and strong. 'But let me measure,' said jolly Robin, 'Before we begin our fray; For I'll not have mine to be longer than thine, For that will be counted foul play.' 'I pass not for length,' bold Arthur replied, 'My staff is of oak so free; Eight foot and a half it will knock down a calf, And I hope it will knock down thee.' Then Robin could no longer forbear, He gave him such a knock, Quickly and soon the blood came down, Before it was ten o'clock. About and about and about they went, Like two wild boars in a chase, Striving to aim each other to maim, Leg, arm, or any other place. And knock for knock they hastily dealt, Which held for two hours and more; That all the wood rang at every bang, They plied their work so sore. In the last century games or matches at cudgels were of frequent occurrence, and public subscriptions were entered into for the purpose of finding the necessary funds to provide prizes. We have in our possession the original subscription list for one of these cudgel matches, which was played for on the 30th of April 1748, at Shrivenham, in the county of Berks, the patrons on that occasion being Lord Barrington, the Hons. Daniel and Samuel Barrington, Witherington Morris, Esq., &c. The amount to be distributed in prizes was a little over five pounds. We find now-a-days pugilists engage in a much more brutal and less scientific display for a far less sum. The game appears to have almost gone out of use in England, although we occasionally hear of its introduction into some of our public schools. WONDERS OF THE GLASTONBURY WATERSUnder the 30th April 1751, Richard Gough enters in his diary: At Glastonbury, Somerset, a man thirty years afflicted with an asthma, dreamed that a person told him, if he drank of such particular waters, near the Chain-gate, seven Sunday mornings, he should be cured, which he accordingly did and was well, and attested it on oath. This being rumoured. abroad, it brought numbers of people from all parts of the kingdom to drink of these miraculous seaters for various distempers, and many were healed, and great numbers received benefit.' Five days after, Mr. Gough added: Twas computed 10,000 people were now at Glastonbury, from different parts of the kingdom, to drink the waters there for various distempers. Of course, a therapeutical system of this kind could not last long. Southey preserves to us in his Common-place Book a curious example of the cases. A young man, witnessing the performance of Hamlet at the Drury Lane Theatre, was so frightened at sight of the ghost, that a humour broke out upon him, which settled in the king's evil. After all medicines had failed, he came to these waters, and they effected a thorough cure. Faith healed the ailment which fear had produced. The last of April may be said to have in it a tint of the coming May. The boys, wisely provident of what was to be required to-morrow, went out on this day to seek for trees from which they might obtain their proper supplies of the May blossom. Dryden remarks the vigil or eve of May day: Waked, as her custom was, before the day, To do th' observance clue to sprightly May, For sprightly May commands our youth to keep The vigils of her night, and breaks their rugged sleep. EARLY HISTORY OF SILK STOCKINGSApril 30th 1560. Sir Thomas Gresham writes from Antwerp to Sir William Cecil, Elizabeth's great minister, 'I have written into Spain for silk hose both for you and my lady, your wife; to whom it may please you I may be remembered.' These silk hose, of black colour, were accordingly soon after sent by Gresham to Cecil. Hose were, up to the time of Henry VIII, made out of ordinary cloth: the king's own were formed of yard-wide taffeta. It was only by chance that he might obtain a pair of silk hose from Spain. His son Edward VI received as a present from Sir Thomas Gresham-Stow speaks of it as a great present-'a pair of long Spanish silk stockings.' For some years longer, silk stockings continued to be a great rarity. 'In the second year of Queen Elizabeth,' says Stow, 'her silk woman, Mistress Montague, presented her Majesty with a pair of black knit silk stockings for a new-year's gift; the which, after a few days wearing, pleased her Highness so well that she sent for Mistress Montague, and asked her where she had them, and if she could help her to any more; who answered, saying, 'I made them very carefully, of purpose only for your Majesty, and seeing these please you so well, I will presently set more in hand.' 'Do so,' quoth the Queen, 'for indeed I like silk stockings so well, because they are pleasant, fine, and delicate, that henceforth I will wear no more cloth stockings.' And from that time to her death the Queen never wore cloth hose, but only silk stockings.' |