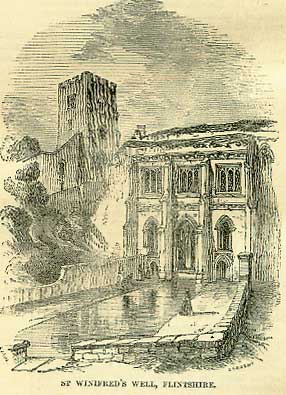

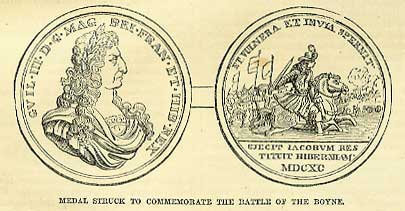

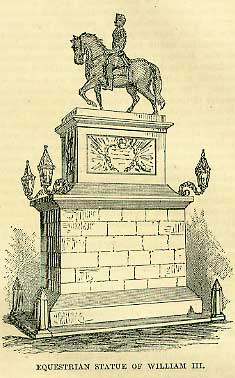

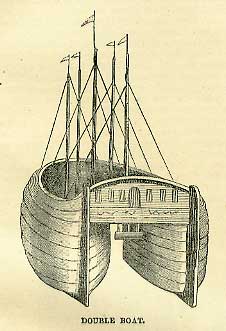

1st JulyBorn: Bishop (Joseph) Hall, 1574, Bristow Park, Leicestershire; Louis Joseph, Due de Vendome, 1654; Jean Baptiste, Comte de Rochambeau, 1725, Vendome; Adam Viscount Duncan, admiral, 1731, Dundee. Died: Edgar, king of England, 975; Admirable Crichton, assassinated at Mantua, 1582; Isaac Casaubon, learned scholar, editor of ancient classics, 1614, bur. Westminster Abbey; Frederick, Duke Schomberg, killed at the Battle of the Boyne, 1690; Edward Lluyd, antiquary, 1709, Oxford; Henry Fox, Lord Holland, 1774; William Huntingdon, 1813, Tunbridge Wells; G. F. von Schubert, German philosophical writer, 1860, Laufzorn, near Munich. Feast Day: Saints Julius and Aaron, martyrs, about 303; St. Thierri, abbot of Mont-d'Hor, 533; St. Calais or Carilephus, abbot of Anille, 542; St. Gal the First, bishop of Clermont, about 553; St. Cybar, recluse at Angouleme, 581; St. Simeon, surnamed Salus, 6th century; St. Leonorus or Lunaire, bishop; St. Rumold, patron of Mechlin, bishop and martyr, 775; St. Theobald or Thibault, confessor, 1066. ISAAC CASAUBON-WALTON'S INITIALSIsaac Casaubon was a foreign scholar of the highest eminence, who came to England in 1610, along with Sir Henry Wotton, the English ambassador at Paris, who had lodged in his house at Geneva, and 'there contracted,' as Isaac Walton tells us, 'a most worthy friendship with that man of rare learning and ingenuity.' Casaubon did not survive his arrival in England above four years. He was buried in the south transept of Westminster Abbey, where a marble mural tablet was erected to him by Bishop Morton. While we have ample record of the friendship-and it was an angling friendship-which subsisted between Isaac Walton and Sir Henry Wotton, we have none regarding any between Walton and Casaubon, beyond the respectful reference to him above quoted, and the presumption arising from Walton having been the friend of Casaubon's friend Wotton. There is, however, some reason in the traditions of Westminster Abbey for believing that Walton, from affection for Casaubon's memory, scratched his initials upon the mural tablet just adverted to. We do find upon the tablet a rude cutting of initials, with a date, as represented on the preceding page. For the mere probability of this being a veritable work of the hand of one so dear to English literature as good Isaac Walton, we have thought the matter worthy of the present notice. HOLY WELLSJuly 1, 1652, the eccentric John Taylor, commonly called the Water Poet, from his having been a waterman on the Thames, paid a visit to St. Winifred's Well, at Holywell, in Flintshire. This was a place held in no small veneration even in Taylor's days; but in Catholic times, it filled a great space indeed. There is something at once so beautiful and so bountiful in a spring of pure water, that no wonder it should become an object of some regard among a simple people. We all feel the force of Horace's abrupt and enthusiastic address, '0 Fons Blandusiae, splendidior vitro,' and do not wonder that he should resolve upon sacrificing a kid to it. In the middle ages, when a Christian tinge was given to everything, the discovery of a spring in a romantic situation, or remarkable for the brightness, purity, or taste of its water, was forthwith followed by its dedication to some saint; and once placed among the category of holy wells, its waters were endued, by popular faith, with powers more or less miraculous. Shrewd Thomas Powell, writing in 1631, says: 'Let them find out some strange water, some unheard-of spring; it is an easy matter to discolour or alter the taste of it in some measure, it makes no matter s how little. Report strange cures that it hath done; beget a superstitious opinion of it. Good-fellowship shall uphold it, and the neighbouring towns shall all swear for it.' So early as 963, the Saxon king Edgar thought it necessary to forbid the 'worshipping of fountains,' and the canons of Anselm (1102) lay it down as a rule, that no one is to attribute reverence or sanctity to a fountain without the bishop's authority. Canons, however powerful to foster superstition, were powerless to control it; ignorance invested springs with sanctity without the aid of the church, and every county could boast of its holy well.  Some of these were held specially efficacious for certain diseases. St. Tegla's Well was patronised by sufferers from 'the falling sickness;' St. John's, Balmanno, Kincardineshire, by mothers whose children were troubled with rickets or sore eyes. The Tobirnimbuadh, or spring of many virtues, in St. Kilda's Isle, was pre-eminent in deafness and nervous disorders; while the waters of Trinity Gask Well, Perthshire, enabled every one baptized therein to face the plague without fear. Others, again, possessed peculiar properties. Thus, St. Loy's Well, Tottenham, was said to be always full but never overflowing; the waters of St. Non's ebbed and flowed with the sea; and those of the Toberi-clerich, St. Kilda, although covered twice in the day by the sea, never became brackish. The most famous holy well in the three kingdoms is undoubtedly that dedicated to St. Winifred (Holywell, Flintshire), at whose shrine Giraldus Cambrensis offered his devotions in the twelfth century, when he says she seemed ' still to retain her miraculous powers.' Winifred was a noble British maiden of the seventh century; a certain Prince Cradocus fell in love with her, and finding his rough advances repulsed, cut off the lady's head. Immediately he had done this, the prince was struck dead, and the earth opening, swallowed up his body. Meanwhile, Winifred's head rolled down the hill; where it stopped, a spring gushed forth, the blood from the head colouring the pebbles over which it flowed, and rendering fragrant the moss growing around. St. Bueno picked up the head, and skilfully reunited it to the body to which it belonged, after which Winifred lived a life of sanctity for fifteen years, while the spring to which she gave her name became famous in the land for its curative powers. The spring rises from a bed of shingle at the foot of a steep hill, the water rushing out with great impetuosity, and flowing into and over the main basin into a smaller one in front. The well is enclosed by a building in the perpendicular Gothic style (dating from the beginning of the reign of Henry VII), which 'forms a crypt under a small chapel contiguous to the parish church, and on a level with it, the entrance to the well being by a descent of about twenty steps from the street. The well itself is a star-shaped basin, ten feet in diameter, canopied by a most graceful stellar vault, and originally enclosed by stone traceried screens filling up the spaces between the supports. Round the basin is an ambulatory similarly vaulted.' The sculptural ornaments consisted of grotesque animals, and the armorial-bearings of various benefactors of the shrine; among them being Catharine of Aragon, Margaret, mother of Henry VII, and different members of the Stanley family, the founders both of the crypt and the chapel above it. Formerly, the former contained statues of the Virgin Mary and St. Winifred. The first was removed in 1635; the fate of Winifred's effigy, to which a Countess of Warwick (1439) bequeathed her russet velvet gown, is unknown. On the stones at the bottom of the well grow the Bissus iolethus, and a species of red Jungermania moss, known in the vulgar tongue as Winifred's hair and blood. In the seventeenth century, St. Winifred could boast thousands of votaries. James II paid a visit to the shrine in 1688, and received the shift worn by his great-grandmother at her execution, for his pains. Pennant found the roof of the vault hung with the crutches of grateful cripples. He says, 'the resort of pilgrims of late years to these Fontanalia has considerably decreased; the greatest number are from Lancashire. In the summer, still a few are to be seen in the water, in deep devotion up to their chins for hours, sending up their prayers, or performing a number of evolutions round the polygonal well; or threading the arches between and the well a prescribed number of times.' An attempt to revive the public faith in the Flintshire saint was made in 1805, when a pamphlet was published, detailing how one Winefred White, of Wolverhampton, experienced the benefit of the virtue of the spring. The cure is certified by a resident of Holywell, named Elizabeth Jones, in the following terms: 'I hereby declare that, about three months ago, I saw a young woman calling herself Winefred White, walking with great difficulty on a crutch; and that on the following morning, the said Winefred White came to me running, and without any appearance of lameness, having, as she told me, been immediately cured after once bathing in St. Winifred's Well.' It was of no avail; a dead belief was not to be brought again to life even by Elizabeth Jones of Holywell. St. Madern's Well, Cornwall, was another popular resort for those who sought to be relieved from aches and pains. Bishop Hall, in his Mystery of Godliness, bears testimony to the reality of a cure wrought upon a cripple by its waters. He says he 'took strict and impartial examination' of the evidence, and found neither art nor collusion-the cure done, the author an invisible God.' In the seventeenth century, however, the well seems to have lost its reputation. St. Madern was always propitiated by offerings of pins or pebbles. This custom prevailed in many other places beside; Mr. Haslam assures us, that pins may be collected by the handful near most Cornish wells. At St. Kilda, none dared approach with empty hands, or without making some offering to the genius of the place, either in the shape of shells, pins, needles, pebbles, coins, or rags. A well near Newcastle obtained the name of Ragwell, from the quantity of rags left upon the adjacent bushes as thank-offerings. St. Tegla, of Denbighshire, required greater sacrifices from her votaries. To obtain her good offices, it was necessary to bathe in the well, walk round it three times, repeating the Lord's Prayer at each circuit, and leave fourpence at the shrine. A cock or hen (according to the patient's sex) was then placed in a basket, and carried round the well, into the churchyard, and round the church. The patient then entered the church, and ensconced him or herself under the communion-table, with a Bible for a pillow, and so remained till daybreak. If the fowl, kept all this while imprisoned, died, the disease was supposed to have been transferred to it, and, as a matter of course, the believer in St. Tegla was made whole. Wells were also used as divining-pools. By taking a shirt or a shift off a sick person, and throwing it into the well of St. Oswald (near Newton), the end of the illness could easily be known-if the garment floated, all would be well; if it sank, it was useless to hope. The same result was arrived at by placing a wooden bowl softly on the surface of St. Andrew's Well (Isle of Lewis), and watching if it turned from or towards the sun; the latter being the favourable omen. A fore-knowledge of the future, too, was to be gained by shaking the ground round St. Madern's Spring, and reading fate in the rising bubbles. At St. Michael's (Banffshire), an immortal fly was ever at his post as guardian of the well. 'If the sober matron wished to know the issue of her husband's ailment, or the love-sick nymph that of her languishing swain, they visited the well of St. Michael. Every movement of the sympathetic fly was regarded with silent awe, and as he appeared cheerful or dejected, the anxious votaries drew their presages.' Of St. Keyne's Well, Cornwall, Carew in his Survey quotes the following descriptive rhymes: In name, in shape, in quality, This well is very quaint; The name to lot of Keyne befell, No over-holy saint. The shape-four trees of divers kind, Withy, oak, elm, and ash, Make with their roots an arched roof, Whose floor the spring doth wash. The quality-that man and wife, Whose chance or choice attains, First of this sacred stream to drink, Thereby the mastery gains. Southey sang of St. Keyne-how the traveller drank a double draught when the Cornishman enlightened him respecting the properties of the spring, and how You drank of the well I warrant betimes? He to the Cornishman said; But the Cornishman smiled as the stranger spake, And sheepishly shook his head. I hastened as soon as the wedding was done, And left my wife in the porch; But i' faith she had been wiser than me, For she took a bottle to church! When Erasmus visited the wells of Walsingham (Norfolk), they were the favourite resort of people afflicted with diseases of the head and stomach. The belief in their medicinal powers afterwards declined, but they were invested with the more wonderful power of bringing about the fulfilment of wishes. Between the two wells lay a stone on which the votary of our Lady of Walsingham knelt with his right knee bare; he then plunged one hand in each well, so that the water reached the wrist, and silently wished his wish, after which he drank as much of the water as he could hold in the hollows of his hands. This done, his wishes would infallibly be fulfilled within the year, provided he never mentioned it to any one or uttered it aloud to himself. While the Routing Well of Inveresk rumbled before a storm of nature's making, the well of Oundle, Northamptonshire, gave warning of perturbations in the world of politics. Baxter writes (World of Spirits, p. 157)- 'When I was a school-master at Oundle, about the Scots coming into England, I heard a well in one Dob's yard, drum like any drum beating a march. I heard it at a distance; then I went and put my head into the mouth of the well, and heard it distinctly, and nobody in the well. It lasted several days and nights, so as all the country-people came to hear it. And so it drummed on several changes of tunes. When King Charles II died, I went to the Oundle carrier at the Ram Inn, Smithfield, who told me the well had drummed, and many people came to hear it.' Not many years ago, the young folks of Bromfield, Cumberland, and the neighbouring villages, used to meet on a Sunday afternoon in May, at the holywell, near St. Cuthbert's Stane, and indulge in various rural sports, during which not one was permitted to drink anything but water from the well. This seems to have been a custom common to the whole county at one time, according to The June Days Jingle: The wells of rocky Cumberland Have each a saint or patron, Who holds an annual festival, The joy of maid and matron. And to this day, as erst they wont, The youths and maids repair, To certain wells on certain days, And hold a revel there. Of sugar-stick and liquorice, With water from the spring, They mix a pleasant beverage, And May-day carols sing. London was not without its holy wells; there was one dedicated to St. John, in Shoreditch, which Stow says was spoiled by rubbish and filth laid down to heighten the plots of garden-ground near it. A pump now represents St. Clement's Well (Strand), which in Henry II's reign was a favourite idling-place of scholars and city youths in the summer evenings when they walked forth to take the air. THE BATTLE OF THE BOYNEThis conflict, by which it might be said the Revolution was completed and confirmed, took place on the 1st of July 1690. The Irish Catholic army, with its French supporters, to the number in all of about 30,000, was posted along with King James on the right bank of the Boyne river, about 25 miles north of Dublin. The army of King William, of rather greater numbers, partly English regiments, partly Protestants of various continental quickly followed by intelligence which changed that joy into sorrow. At an early hour on Tuesday, the 1st of July-a bright and beautiful summer morning the right wing of the Protestant army made a detour by the bridge of Slane, to fall upon the left of the Irish host, while William conducted his left across the river by a ford, several miles in the other direction. The main body crossed directly, and found some difficulty in doing so, so that if well met by the enemy, they might have easily been defeated. But countries, approached the river from the north. Although the river was fordable, it was considered that James's army occupied a favourable position for resistance.  In the course of the day before the battle, the Irish army got an opportunity of firing a cannon at King William, as he was on horseback inspecting their position; and he was slightly wounded in the shoulder. The news that he was slain spread to Paris, Rome, and other strongholds of the Catholic religion, diffusing great joy; but it was the great mass of the Irish foot did not stop to fight; they ran away. For this their want of discipline, aided by lawless habits, is sufficient to account, without supposing that they were deficient in courage. Such panics, as we now know better than ever, are apt to happen with the raw troops of all countries. The Irish horse made a stout resistance; but when King William, having crossed the river, came upon them in flank, they were forced to retire. Thus, in a few hours, a goodly army was completely dissipated. King James pusillanimously fled to Dublin, as soon as he saw that the day was going against him. Nor did he stop till he had reached France, bringing everywhere the news of his own defeat. So it was that King William completed the triumph of the Protestant religion in these islands. The anniversary of the day has ever since been held in great regard by the Protestants in Ireland. As it gave them relief from the rule of the Catholic majority, the holding of the day in affectionate remembrance was but natural and allowable. Almost down to our time, however, the celebration has been managed with such strong external demonstrations-armed musterings, bannered processions, glaring insignia, and insulting party-cries -as could not but be felt as grievous by the Catholics; and the consequence has been that the fight begun on Boyne Water in 1690, has been in some degree renewed every year since. In private life, to remind a neighbour periodically of some humiliation he once incurred, would be accounted the perfection of bad-manners-how strange that a set of gallant gentlemen, numbering hundreds of thousands, should be unable to see how unpolite it is to keep up this 1st of July celebration, in the midst of a people whose feelings it cannot fail to wound! MISADVENTURES OF A STATUEThe services of King William in securing the predominance of the Protestant religion in Ireland, were acknowledged by the erection of an equestrian statue of him in College Green, Dublin. This work of art, composed of iron with a coating of lead, and solemnly inaugurated in 1701, has lived a very controversial life ever since-never, it may be said, out of hot water. Rather oddly, while looked on with intense hatred by Catholics, even the Protestant lads of the college did not like it-for why, it turned its tail upon the university!  So, ever since that solemn affair in 1701, this unfortunate semblance of the hook-nosed Nassau has been subjected to incessant maltreatment and indignity, all magisterial denunciations notwithstanding. Some of the outrages committed upon it were of a nature rather to be imagined than described. On the 27th of June 1710, it was found to have been feloniously robbed of its regal sword and martial baton. The act was too gross to be overlooked. The corporation offered a reward of a hundred pounds for the discovery of the culprit or culprits; and three students of Trinity College were consequently accused, tried, and condemned to suffer six months' imprisonment, to pay a fine of one hundred pounds each, and to be carried to College Green, and there to stand before the statue, for half an hour, with this inscription on each of their breasts 'I stand here for defacing the statue of our glorious deliverer, the late King William.' On account of their loss of prospects by expulsion from the college, and loss of health by incarceration in a noisome dungeon, the latter part of the sentence was remitted, and the fine reduced to five shillings. But neither severity nor lenity in the authorities seemed to afford the statue any protection; just four years after the students' affair, the baton was again taken away, and though another reward of one hundred pounds was offered, the evil-doers were not discovered. Twice a year, on the anniversaries of the battle of the Boyne, and birthday of King William, the statue was cleaned, white-washed, and decorated with a scarlet cloak, orange sash, and other appurtenances; while a bunch of green ribbons and shamrocks was symbolically placed beneath the horse's uplifted foot. Garlands of orange lilies, and streamers of orange ribbons, bedecked the honoured horse, while drums, trumpets, and volleys of musketry made the welkin ring in honour of the royal hero. Moreover, every person who chanced to pass that way, and did not humbly take off his hat, was knocked down, and then mercilessly kicked for presuming to fall in the presence of so noble a prince. As a natural consequence of these proceedings, during the other 363 days of the year, the then undressed and unprotected statue was so liberally besmeared with filth by the anti-Orange party, as to be a disgrace to a civilised city. To chronicle all the mishaps of this statue, would require a volume. Many must be passed over; but one that occurred in the eventful year 1798, is worthy of notice. A well-known eccentric character, named Watty Cox, for many years the editor of The Irish Magazine, having been originally a gunsmith, was expert in the use of tools, and being much annoyed by the helpless statue, he tried, one dark night, to file off the monarch's head. But the inner frame of iron foiled, as the Dublin wits said, the literary filer's foul attempt. In 1805, the 4th of November falling upon a Sunday, the usual riotous demonstration around the statue was postponed till the following day. On the Saturday night, however, the watchman on College Green was accosted by a man, seemingly a painter, who stated that he had been sent by the city authorities to decorate the statue for the approaching festivities of the Monday; adding that the apprehended violence of the disaffected portion of the populace rendered it advisable to have the work done by night. The unsuspecting watchman assisted the painter in mounting the statue, and the latter plied his brush most industriously for some time. Then descending, he coolly requested the watchman to keep an eye to his painting utensils, while he went to his master's house for some more colours, necessary to complete the work. The night, however, passed away without the return of the painter, and at daybreak, on Sunday morning, the statue was found to be completely covered with an unctuous black pigment, composed of grease and tar, most difficult to remove; while the bucket that had contained the mixture was suspended by a halter fixed round the insulted monarch's neck. This act caused the greatest excitement among the Orange societies; but most fortunately for himself and friends, the adventurous artist was never discovered. The annual custom of decorating the statue, so provocative of religious and political rancour, and the fertile source of innumerable riots, not unattended with loss of life, was put down by the enlightened judgment of the authorities, combined with the strong arm of the law, in 1822; and the miserable monument suffered less rough usage, until its crowning catastrophe happened in 1836. One midnight, in the April of that year, the statue blew up, with a terrific explosion, smashing and extinguishing the lamps for a considerable distance. The body was blown in one direction, the broken legs and arms in another, and the wretched horse, that had suffered so many previous injuries, was shattered to pieces. An offered reward of £200 failed to discover the perpetrators of this deed. The statue was repaired and replaced in its old position. Like an old warrior, who had seen long service and suffered many wounds, it gradually acquired a certain degree of respect, even from its enemies. The late Daniel O'Connell, during his year of mayoralty, caused it to be bronzed, thereby greatly improving its appearance: and ever since it has remained an ornament, instead of a disgrace, to the capital of Ireland. THE CHEVALIER DE LA BARREThe case of Thomas Aikenhead, a youth hanged in Scotland in 1695, at the instigation of the clergy, for the imaginary crime of blasphemy, finds an exact parallel in a later age in France. A youth of nineteen, named the Chevalier de la Barre, was decapitated and than burned at Abbeville, on the 1st of July 1765, for mutilating a figure of Christ, which stood on the bridge of that town, this offence being regarded as sacrilege, for which a decree of Louis XIV had assigned a capital punishment. Even when the local judgment on this unfortunate young man was brought for review before the parliament of Paris, there was a majority of fifteen to ten for confirming the sentence; so strongly did superstition still hold the minds of the upper classes in France. Does it not in some measure explain the spirit under which Voltaire, Diderot, and others were then writing? It is to be admitted of the first of these writers, amidst all that is to be reprobated in his conduct, that he stood forth as the friend of humanity on several remarkable occasions. His energy in obtaining the vindication of the Calas family will always redound to his praise. He published an account of the case of the Chevalier de in Barre, from which it appears that his persecutors gave him at the last for a confessor and assistant a Dominican monk, the friend of his aunt, an abbess in whose convent he had often supped. When the good man wept, the chevalier consoled him. At their last dinner, the Dominican being unable to eat, the chevalier said to him: ' Pray, take a little nourishment; you have as much need of it as I to bear the spectacle which I am to give.' The scaffold, on which five Parisian executioners were gathered, was mounted by the victim with a calm courage; he did not change colour, and he uttered no complaint, beyond the remark: ' I did not believe they could have taken the life of a young man for so small a matter.' THE FIRST STEAMER ON THE THAMESThe London newspapers in 1801 contained the following very simple announcement, in reference to an event which took place on the 1st of July, and which was destined to be the precursor of achievements highly important to the wellbeing of society: An experiment took place on the river Thames, for the purpose of working a barge or any other heavy craft against tide by means of a steam-engine on a very simple construction. The moment the engine was set to work, the barge was brought about, answering her helm quickly; and she made way against a strong current, at the rate of two miles and a half an hour. The historians of steam-navigation seem to have lost sight of this incident. But in truth it was only a small episode in a series, the more important items of which had already appeared in Scotland. Mr. Patrick Miller, banker, Edinburgh, made literally the first experiments in steam-navigation in this hemisphere. [There were some similarly obscure experiments at an earlier date in America.] Mr. Miller's own plan at the first was to have a double boat, with a wheel in the centre, to be driven by man's labour. Annexed is a copy of a contemporary drawing of his vessel, which was ninety feet long, and cost £3000. It proved a failure by reason of the insupportable labour required to drive the wheel. His sons' tutor, Mr. James Taylor, then suggested the application of the steam-engine as all that was necessary for a triumph over wind and tide, and he was induced, with the practical help of a mechanician named Symington, recommended by Taylor, to get a smaller vessel so fitted up, which was actually tried with success upon the lake near his mansion of Dalswinton, in Dumfriesshire, in October 1788, the boat going at the rate of five miles an hour.  The little steam-engine used in this interesting vessel is preserved in the Andersonian Museum at Glasgow. Encouraged by this happy trial and the applause of his friends, Mr. Miller bought one of the boats used upon the Forth and Clyde Canal, and employed the Carron Iron Company to make a steam-engine on a plan devised and superintended by Symington. On the 26th of December 1789, the steamer thus prepared, tugged a heavy load on the above-named canal, at the speed of seven miles an hour. For some reason or other, nothing further was done for many years; the boat was dismantled and laid up. From this time we hear no more of Mr. Miller; he turned his attention to other pursuits, chiefly of an agricultural nature. Mr. Taylor, without his patron, could do nothing. In 1801, Lord Dundas, who was largely interested in the success of the canal, employed Symington to make experiments for working the canal trade by steam-power instead of horse-power. A steamer was built, called the Charlotte Dundas-the first ever constructed expressly for steam-navigation, its predecessors having been mere make-shifts. A steam-engine was made suitable for it; and early in 1802, the boat drew a load of no less than seventy tons at a rate of three miles and a quarter per hour, against a strong gale. An unexpected obstacle dashed the hopes of the experimenters; some one asserted that the surf or wave occasioned by the motion of the steamer would damage the banks of the canal; the assertion was believed, and the company declined any further experiments. What took place after another interval of discouragement and inaction will be related in another place. |