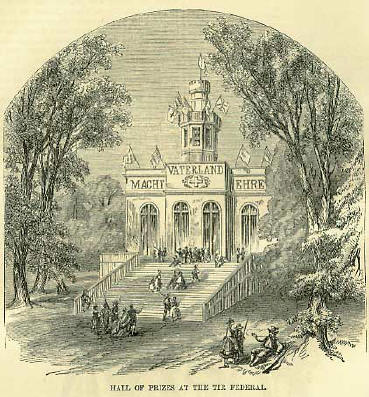

2nd JulyBorn: Archbishop Cranmer, 1489,Aslacton, Notts; Frederick Theophilus Klopstock, German poet, 1724, Quedlinburg, Saxony; Henry, third Marquis of Lansdowne, statesman, 1780; Joseph John Gurney, Quaker philanthropist, 1788, Earlhaim Hall, near Norwich. Died: Henry I, emperor of Germany (the Fowler), 936; Michael Nostradamus (predictions), 1566, Salon; Jean Jacques Rousseau, 1778, Ermenonville; Dionysius Diderot, philosophical writer, 1784, Paris; Dr. Hahnemann, originator of homoeopathy, 1843, Paris; Sir Robert Peel, statesman, 1850, London; William Berry (works on heraldry), 1851, Brixton. Feast Day: The Visitation of the Blessed Virgin. Saints Processus and Martinian, martyrs, 1st century. St. Monegondes, recluse at Tours, 570. St. Oudoceus, bishop of Llandaff, 6th century. St. Otho, bishop of Bamberg, confessor, 1139. VISITATION OF THE VIRGIN MARYIn the Romish church, the visit paid by the Virgin Mary to her cousin Elizabeth (St. Luke i. 39, 40) is celebrated by a festival on this day, instituted by Pope Urban VI in 1383; which festival continues to be set down in the calendar of the reformed Anglican Church. KLOPSTOCKThe German poet Klopstock enjoyed a great celebrity in his own day, not less on account of his Odes, many of which are excellent, than for that more ambitious sacred poem, called The Messiah, upon which the fabric of his fame was first built. This celebrated epic was written in hexameters, a species of verse little employed by his predecessors, but not uncongenial to German rhythm. Klopstock formed himself on Milton and Young, and is styled in his own country the Milton of Germany: but he soars rather with the wing of the owl than the wing of the eagle. His ode To Young, as the composition of a stranger, will be interesting to English readers, and serves very well as a clue to his genius. TO YOUNG-1752 Die, aged prophet: lo, thy crown of palms Has long been springing, and the tear of joy Quivers on angel-lids Astart to welcome thee. Why linger? Hast thou not already built Above the clouds thy lasting monument? Over thy night-thoughts, too, The pale free-thinkers watch, And feel there's prophecy amid the song, When of the dead-awakening trump it speaks, Of coming final doom, And the wise will of heaven. Die: thou hast taught me that the name of death Is to the just a glorious sound of joy: But be my teacher still, Become my genius there. The language of this ode approaches to a style which in English is termed bathos. As a proof of the wide-spread fame which Klopstock acquired in his own country, we briefly subjoin the account of his funeral, in the words of Mr. Taylor's Historical Survey of German Poetry: 'Klopstock died in 1803, and was buried with great solemnity on the 22nd of March, eight days after his decease. The cities of Hamburg and Altona concurred to vote him a public mourning; and the residents of Denmark, France, Austria, Prussia, and Russia joined in the funeral-procession. Thirty-six carriages brought the senate and magistracy, all the bells tolling; a military procession contributed to the order and dignity of the scene; vast bands of music, aided by the voices of the theatre, performed appropriate symphonies, or accompanied passages of the poet's works. The coffin having been placed over the grave, the preacher, Meyer, lifted the lid, and deposited in it a copy of The Messiah; laurels were then heaped on it; and the death of Martha, from the fourteenth book, was recited with chaunt. The ceremony concluded with the dead mass of Mozart.' THE PROPHECIES OF NOSTRADAMUS Princes, and other great people, besides many learned men, three centuries ago, paid studious attention to a set of mystic prophecies in French quatrains, which had proceeded from a Provencal physician, named Nostradamus, and were believed to foreshadow great historical events. These pre-dictions had been published in a series of little books, containing each a hundred, and they were afterwards collected into one volume. Our copy of Nostradamus is one published in London in 1672, with English translations and notes, by a refugee French physician, named Theophilus de Garencieres, who had himself a somewhat remarkable history. Wood informs us that he died of a broken heart, in consequence of the ill-usage he received from a certain knight. He himself, though a doctor of Oxford, and member of the Royal College of Physicians of London, appears to have been a devout believer in the mystic enunciations which he endeavoured to represent in English. He had, indeed, imbibed this reverence for the prophet in his earliest years, for, strange to say, the brochures containing these predictions were the primers used about 1618 in the schools of France, and through them he had learned to read. The frontispiece of the English translation represents Garencieres as a thin elderly man with a sensitive, nervous-bilious countenance, seated, in a black gown with wig and bands, at a table, with a book and writing materials before him, and also a carafe bottle containing what appears as figures of the sun and crescent moon. Michael Nostradamus (the name was a real one) saw the light at St. Remy, on the 14th of December 1503, and died, as our prefatory list informs us, on the 2nd of July 1566. He studied mathematics, philosophy, and physic, and appears to have gained reputation as a medical man before becoming noted as a mystogogue. He was twice married, and had several children; he latterly was settled at Salon, a town between Marseille and Avignon. It was with the view of improving his medical gifts that he studied astrology, and thus was led to foretell events. His first efforts in this line took the humble form of almanac-making. His almanacs became popular; so much so, that imitations of them appeared, which, being thought his, and containing nothing but folly, brought him discredit, and caused the poet Jodelle to salute him with a satirical couplet: Nostra damns cum falsa damns, nam fallere nostra est, Et cum falsa damns, nil nisi Nostra damns. That is: 'We give our own things when we give false things, for it is our peculiarity to deceive, and when we give false things, we are only giving our own things.' His reputation was confirmed by the publication, in 1555, of some of his prophecies, which attracted so much regard, that Henry II sent for him to Paris, and consulted him about his children. One of these, when king under the name of Charles IX, making a progress in Provence in 1564, did not fail to go to Salon to visit the prophet, who was commissioned by his fellow-townsmen to give the young monarch a formal reception. Charles, and his mother, Catharine de' Medici, also sent for him on one occasion to Lyon, where each gave him a considerable present in gold, and the king appointed him his physician. Many of his contemporaries thought him only a doting fool; but that the great bulk of French society was impressed by his effusions, there is no room to doubt. The quatrains of the Salon mystic, are set forth by himself as arising from judicial astrology, with the aid of a divine inspiration. 'I am,' he said, 'but a mortal man, and the greatest sinner in the world; but, being surprised occasionally by a prophetical humour, and by a long calculation, pleasing myself in my study, I have made books of prophecies, each one containing a hundred astronomical stanzas.' We are to understand that Nostradamus lived much in solitude-spent whole nights in his study, withdrawn into intense meditation-and considered himself as thus attaining to a participation in a supernatural knowledge flowing directly from God. He was probably quite sincere in believing that coming events cast their shadows on his mind. Nor are we left without instances of his acting much as the seer of the Scottish Highlands in the midst of the ordinary affairs of life. One day, being at the castle of Faim, in Lorraine, attending on the sick mother of its proprietor the Lord of Florinville, he chanced to walk through the yard, where there were two little pigs, one white, the other black. The lord inquired in jest, what should come of these two pigs. He answered presently: 'We shall eat the black, and the wolf shall eat the white.' The Lord Florinville, intending to make him a liar, did secretly command the cook to dress the white for supper. The cook then killed the white, dressed it, and spitted it ready to be roasted, when it should he time. In the meantime, having some business out of the kitchen, a young tame wolf came in and ate up the buttocks of the white pig. The cook coming in, and fearing lest his master should be angry, took the black one, killed, and dressed it, and offered it at supper. The lord, thinking he had got the victory, not knowing what was befallen, said to Nostradamus: 'Well, sir, we are now eating the white pig, and the wolf shall not touch it.' 'I do not believe it,' said Nostradamus; 'it is the black one that is upon the table.' Presently the cook was sent for, who confessed the accident, the relation of which was as pleasing to them as any meat.' The prophecies of the Salon seer appear to us, in these modern days, as vague and incoherent rhapsodies, extremely ill adapted for being identified with any actual event. And even when it is possible to say that some particular event seems faintly intimated in one of these quatrains, it is generally accompanied by something else so irrelevant, that we are induced almost irresistibly to trace it to accident. One of the predictions which most conduced to raise his reputation, was the following: Le Lion jenne le vieux surmontera, En champ bellique par singulier duelle, Dans cage d'or I'ceil il lui crevera, Deltic playes une puis mourir mort cruelle. [The young lion shall overcome the old one, In martial field by a single duel, In a golden cage he shall put out his eye, Two wounds from one; then shall he die a cruel death.] It was thought that this prophecy, uttered in 1555, was fulfilled when Henry II, in 1559, tilting with a young captain of his guard, at a tournament, received a wound from the splinter of a lance in the right eye, and died of it in great pain, ten days after. But here we must consider these two combatants as properly called lions; we must take the king's gilt helmet for the golden cage; and consider the imposthume which the wound created, as a second wound; all of them concessions somewhat beyond what we can regard as fair. Another of the predictions thought to be clearly fulfilled, was the following: Le sang de juste a Londres sera faute, Brulez par feu, de vingt et trois, les Six, La Dame antique cherra de place haute De meme secte plusieurs seront occis. [The blood of the just shall be wanting in London, Burnt by fire of three and twenty, the Six, The ancient dame shall fall from her high place, Of the same sect many shall be killed.] It was supposed that the death of Charles I, and the fire of London, were here adumbrated; but the correspondence between the language and the facts is of the most shadowy kind. Another line, Le Senat de Londres metteront a, mort le Roy,' appears a nearer hit at the bloody scene in front of Whitehall. There is also some felicity in 'Le Oliver se plantera en terra firme,' if we can render it as, 'Oliver will get a footing on the continent,' and imagine it as referring to Cromwell's success in Flanders. Still, even these may be regarded as only chance hits amongst a thousand misses. One learns with some surprise that, well on in the eighteenth century, there was a lingering respect for the dark sayings of Nostradamus. Poor Charles Edward Stuart, in his latter days, scanned the mystic volume, anxious to find in it some hint at a restoration of the right royal line of Britain. Connected with Nostradamus and the town of Salon, there is a ghost-story of a striking character, which we believe is not much known, and may probably amuse the faculty of wonder in a considerable portion of the readers of the Book of Days. It was in the month of April 1697, that a spirit, which some believed to be no other than that of the great prophet, appeared to a man of the humbler class at Salon, commanding him on pain of death to observe inviolable secrecy in regard of what he was about to deliver. 'This done, it ordered him to go to the intendant of the province, and require, in its name, letters of recommendation, that should enable him, on his arrival at Versailles, to obtain a private audience of the king. 'What thou art to say to the king,' continued the apparition, 'thou wilt not be informed of till the day of thy being at court, when I shall appear to thee again, and give thee full instructions. But forget not that thy life depends upon the secrecy which I enjoin thee on what has passed between us, towards every one, only not towards the intendant.' At these words the spirit vanished, leaving the poor man half dead with terror. Scarcely was he come a little to himself, when his wife entered the apartment where he was, perceived his uneasiness, and inquired after the cause. But the threat of the spectre was yet too much present to his mind, to let her draw a satisfactory answer from him. The repeated refusals of the husband did but serve to sharpen the curiosity of the wife; the poor man, for the sake of quietness, had at length the indiscretion to tell her all, even to the minutest particulars: and the moment he had finished his confession, he paid for his weakness by the loss of his life. The wife, violently terrified at this unexpected catastrophe, persuaded herself, however, that what had happened to her husband might be merely the effect of an overheated imagination, or some other accident; and thought it best, as well on her own account, as in regard to the memory of her deceased husband, to confide the secret of this event only to a few relations and intimate friends. 'But another inhabitant of the town, having, shortly after, the same apparition, imparted the strange occurrence to his brother; and his imprudence was in like manner punished by a sudden death. And now, not only at Salon, but for more than twenty miles around, these two surprising deaths became the subject of general conversation. 'The same ghost again appeared, after some days, to a farrier, who lived only at the distance of a couple of houses * from the two that had so quickly died; and who, having learned wisdom from the misfortune of his neighbours, did not delay one moment to repair to the intendant. It cost him great trouble to get the private audience, as ordered by the spectre, being treated by the magistrate as a person not right in the head. 'I easily conceive, so please your excellency,' replied the farrier, who was a sensible man, and much respected as such at Salon, that I must seem in your eyes to be playing an extremely ridiculous part; but if you would be pleased to order your sub-delegates to enter upon an examination into the hasty death of the two inhabitants of Salon, who received the same commission from the ghost as I, I flatter myself that your excellency, before the week be out, will have me called.' In fact, Francois Michel, for that was the farrier's name, after information had been taken concerning the death of the two persons mentioned by him, was sent for again to the intendant, who now listened to him with far greater attention than he had done before; then giving him dispatches to Mons de Baobefieux, minister and secretary of state for Province, and at the same time presenting him with money to defray his travelling expenses, wished him a happy journey. 'The intendant, fearing lest so young a minister as M. de Baobefieux might accuse him of too great credulity, and give occasion to the court to make themselves merry at his expense, had enclosed with the dispatches, not only the records of the examinations taken by his sub-delegates at Salon, but also added the certificate of the lieutenant-general de justice, which was attested and subscribed by all the officers of the department. Michel arrived at Versailles, and was not a little perplexed about what he should say to the minister, as the spirit had not yet appeared to him again according to its promise. But in that very night the spectre threw open the curtains of his bed, bid him take courage, and dictated to him, word for word, what he was to deliver to the minister, and what to the king, and to them alone. 'Many difficulties will be laid in thy way,' added the ghost, 'in obtaining this private audience; but beware of desisting from thy purpose, and of letting the secret be drawn from thee by the minister or by any one else, as thou wouldst not fall dead upon the spot' The minister, as may easily be imagined, did his utmost to worm out the mystery: but the farrier was firm, and kept silence, swore that his life was at stake, and at last concluded with these words: that he might not think that what he had to tell the king was all a mere farce, he need only mention to his majesty, in his name, 'that his majesty, at the last hunting-party at Fontainebleau, had himself seen the spectre; that his horse took fright at it, and started aside; that his majesty, as the apparition lasted only a moment, took it for a deception of sight, and therefore spoke of it to no one.' This last circumstance struck the minister; and he now thought it his duty to acquaint the king of the farrier's arrival at Versailles, and to give him an account of the wonderful tale he related. But how great was his surprise, when the monarch, after a momentary silence, required to speak with the farrier in private, and that immediately! 'What passed during this extraordinary inter-view never transpired. All that is known is, that the spirit-seer, after having stayed three or four days at court, publicly took leave of the king, by his own permission, as he was setting out for the chase. 'It was even asserted that the Duc de Duras, captain of the guard in waiting, was heard to say aloud on the occasion: 'Sire, if your majesty had not expressly ordered me to bring this man to your presence, I should never have done it, for most assuredly he is a fool!' The king answered smiling: 'Dear Duras, thus it is that men frequently judge falsely of their neighbour; he is a more sensible man than you and many others imagine.' 'This speech of the king's made great impression. People exerted all their ingenuity, but in vain, to decipher the purport of the conference between the farrier and the king and the minister Baobefieux. The vulgar, always credulous, and consequently fond of the marvellous, took it into their heads that the imposts, which had been laid on by reason of the long and burdensome war, were the real motives of it, and drew from it happy omens of a speedy relief; but they, nevertheless, were continued till the peace. 'The spirit-seer having thus taken leave of the king, returned to his province. He received money of the minister, and a strict command never to mention anything of the matter to any person, be he who he would. Roullet, one of the best artists of the time, drew and engraved the portrait of this farrier. Copies are still existing in several collections of prints in Paris. That which the writer of this piece has seen, represented the visage of a man from about thirty-five to forty years of age; an open countenance, rather pensive, and had what the French term physionomie de caractere.' THE TIR FEDERAL, OR RIFLE-SHOOTING MATCH IN SOLEURESwiss have been famed for the use of the rifle long before English volunteers disputed the prize of all nations with them. Their national gathering is the greatest festival in the year, and is got up in so picturesque a style, that the tourist may well tarry a few days in order to have an opportunity of witnessing it, when he may also observe the national manners and costume more closely than he will be able to do in a hasty tour through the country. It is held at each of the capitals of the cantons in turn the first week in July, commencing invariably on a Sunday. On Saturday evening, all the hotels are crowded for the opening procession next Sunday morning. From six A.M. on that day until nine, on the occasion when the writer was present, the broad flight of steps leading up to the cathedral at Soleure was crowded by worshippers.  Mass was repeated again and again to each relay, and then, the religious duties of the day being over, all gave themselves up to pleasure. The streets were one mass of people waiting for the procession. The burning sun of a beautiful summer-day lightened up the scene, the cannon roared, bands of music added their sweet tones, and the variety of a hundred gay and fantastic costumes dazzled the eye of the amused spectator in the windows. Then came the cry: 'Here is the procession.' At its head walked the juniors, with two pieces of cannon and fifty guns; behind them a man in the costume of William Tell, the patron of riflemen, preceded the body of markers, who were dressed in bright-red blouses with white cordings, carrying at the end of a stick the white disks which serve to mark the shots. Then came the military band, followed by the committee carrying the federal banner, bearing the motto: 'LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY. The deputations of marksmen from each canton, in the greatest variety of picturesque costume, followed: those of Soleure wearing gray felt-hats, adorned with green ribbons; the Hanseatic towns, Bremen and Lubeck, sent their quota, dressed in rich green and gold coats, with a high-crowned hat adorned with a plume of feathers. Most of those present had a bouquet of flowers in the front of their hats, no doubt given by some fair friend.  The shooting ground was about half a mile from the city, a beautiful plain, surrounded by the Vosges Mountains. A splendid avenue of trees led up to the gay pavilion of glass, where the prizes for the successful competitors were hung. They consisted of watches, rifles, cups, gold and silver dishes, coffers, and purses filled with gold Napoleons, amounting in all to a hundred and fifty thousand francs. To the left was the stand for the shooters, a long covered shed opposite twenty-seven targets, furnished with long tables for the convenience of loading. At each successful shot a paper ticket was given to the marksman, which he stuck in the ribbon of his hat; at the end of the day they were presented and counted up, and he who could return into the city in the evening with a hatful received much applause. Not the least amusing part was to turn to the right, and walk through the magnificent dining-room, and then I into the temporary kitchens, where hundreds of cooks were preparing substantial roast and boiled joints of meat, with puddings and pies innumerable. The writer could not help thinking how much better they manage the commissariat department abroad than in England, where the cold pork-pie and glass of ale is the usual refreshment at rifle reviews. The women take a very active part in the success of their brothers or lovers. Most of them were without bonnets: the Unterwalden, in their singular fan-like lace head-dress; the Bernese, in their wide-brimmed hats; the Loe'che, with the circle of plaited ribbon, giving a most singular aspect to the scene; whilst the velvet corsage, white habit-shirt and sleeves, silver chains, and short petticoat bordered with red, is the picturesque costume of most of the women. The shooting usually lasts from Sunday to Sunday, though some-times, from the number of competitors, it is prolonged for a few days. The holders of prizes receive an enthusiastic ovation, each returning to his family and business with the reassuring sentiment that he belongs to one vast family, bearing this device: 'One for all, and all for one.' OLD SCARLETT Died, July 2, 1591, Robert Scarlett, sexton of Peterborough Cathedral, at the age of 98, having buried two generations of his fellow-creatures. A portrait of him, hung up at the west end of that noble church, has perpetuated his fame, and caused him to be introduced in effigy in various works besides the present. And what a lively effigy short, stout, hardy, and self-complacent, perfectly satisfied, and perhaps even proud of his profession, and content to be exhibited with all its insignia about him! Two queens had passed through his hands into that bed which gives a lasting rest to queens and to peasants alike. An officer of Death, who had so long defied his principal, could not but have made some impression on the minds of bishop, dean, prebends, and other magnates of the cathedral, and hence we may suppose the erection of this lively portraiture of the old man, which is believed to have been only once renewed since it was first put up. Dr. Dibdin, who last copied it, tells us that 'old Scarlett's jacket and trunk-hose are of a brownish red, his stockings blue, his shoes black, tied with blue ribbands, and the soles of his shoes red. The cap upon his head is red, and so also is the ground of the coat armour. The following verses below the portrait are characteristic of his age: You see old Scarlett's picture stand on hie; But at your feet here doth his body lye. His gravestone doth his age and death-time shew, His office by heis token[s] you may know. Second to none for strength and sturdy lymm, A scare-babe mighty voice, with visage grim; He had interd two queenes within this place And this townes householders in his life's space Twice over, but at length his own time came, What he for others did, for him the same Was done: no doubt his soule doth live for aye, In heaven, though here his body clad in clay. The first of the queens interred by Scarlett was Catharine, the divorced wife of Henry VIII, who died in 1535 at Kimbolton Castle, in Huntingdon-shire. The second was Mary Queen of Scots, who was beheaded at Fotheringay in 1587, and first interred here, though subsequently transported to Westminster Abbey. A droll circumstance, not very prominent in Scarlett's portrait, is his wearing a short whip under his girdle. Why should a sexton be invested with such an article? The writer has not the least doubt that old Robert required a whip to keep off the boys, while engaged in his professional operations. The curiosity of boys regarding graves and funerals is one of their most irrepressible passions. Every grave-digger who works in a churchyard open to the public, knows this well by troublesome experience. An old man, who about fifty years ago pursued this melancholy trade at Falkirk, in Scotland, always made a paction with the boys before beginning-'Noo, laddies, ye maun bide awa for a while, and no tramp back the mools into the grave, and I'll be sure to bring ye a' forrit, and let ye see the grave, when it's dune.' CHILDREN DETAINED FOR A FATHER'S DEBTOn the 2nd of July 1839, a singular trial came on before the Tribunal de Premiere Instance, at Paris, to determine whether the children of a debtor may be detained by the creditor as a pledge for the debt. Mr. and Mrs. -----, with five children, and some domestic servants, lived for a time at a large hotel at Paris; and as they could not or would not pay their account, they removed to a smaller establishment, the Hotel Britannique, the owner of which consented to make himself responsible for the debt to the other house. After the family had remained with him for a considerable time, Mr. - disappeared, and never returned to the hotel, sending merely a letter of excuses. Then Mrs. - went away, leaving the children and servants behind. The servants were discharged; but the hotel-keeper kindly supported the five children thus strangely left on his hands, until his bill had run up to the large sum of 20,000 francs (about £800). A demand was then made upon him (without revealing to him the present dwelling-place of the parents) to deliver up the children; he refused, unless the bill was paid; whereupon a suit was instituted against him. M. Charles Ledru, the advocate for the parents, passed the highest encomiums on the generous hotel-keeper, and said that he himself would use all his influence to induce the father to pay the debt so indisputably due; but added, that his own present duty was to contend against the detention of the children as a pledge for the debt. The president of the tribunal, M. Debelleyme, equally praised the hotel-keeper, but decided that the law of France would not permit the detention of the children. They were given up, irrespective of the payment of the debt, which was left to be enforced by other tribunals. |