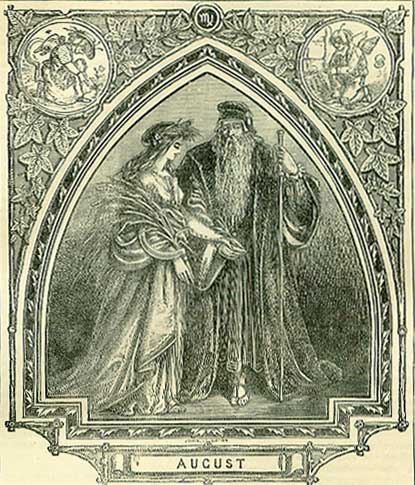

August The eighth was August, being rich arrayed In garment all of gold, down to the ground: Yet rode he not, but led a lovely maid Forth by the lily hand, the which was crowned With ears of corn, and full her hand was found. That was the righteous Virgin, which of old Lived here on earth, and plenty made abound; But after wrong was loved, and justice sold, She left th' unrighteous world, and was to heaven extolled. DESCRIPTIVEAugust comes, and though the harvest though the harvest-fields are nearly ripe and ready for the sickle, cheering the heart of man with the prospect of plenty that surrounds him, yet there are signs on every hand that summer is on the wane, and that the time is fast approaching when she will take her departure. We catch faint glances of autumn peeping stealthily through openings where the leaves have already fallen, and among berries where summer hung out her blossoms; and sometimes hear his rustling footstep among the dry seed-vessels, which have usurped the place of her flowers. Though the convolvulus still throws its straggling bells about the hedges, the sweet May-buds are dead and gone, and in their place the green haws hang crudely upon the branches. The winds come not a-Maying amongst them now. Nearly all the field-flowers are gone; the beautiful feathered grasses that waved like gorgeous plumes in the breeze and sunshine are cut down and carried green flowerless after-math. Many of the birds that sung in the green chambers which she hung for them with her richest arras, have left her and gone over the sea. What few singers remain are silent, and preparing for their departure; and when she hears the robin, his song comforts her not, for she knows that he will chant a sweeter lay to autumn, when she lies buried beneath the fallen leaves. Musing at times over her approaching end, upon the hillsides, they are touched by her beauty, and crimson up with the flowers of the heather, and long leagues of wild moorland catch the reflected blush, which, goes reddening up like sunshine along the mountain slopes. The blue harebell peeps out in wonder to see such a land of beauty, and seems to shake its fragile bells with delight. In waste-places, the tall golden-rod, the scarlet poppy, and the large ox-eyed daisy muster, as if for a procession, and there wave their mingled banners of gold, crimson, and silver, as summer passes by, while the little eyebright, nestling among the grass, looks up and shews its white petals, streaked with green and gold. But, far as summer has advanced, several of her beautiful flowers and curious plants may still be found in perfection in the water-courses, and beside the streams-pleasanter places to ramble along than the dusty and all but flowerless waysides in August. There we find the wild-mint, with its lilac-coloured blossoms, standing like a nymph knee-deep in water, and making all the air around fragrant. And all along the margin by where it grows, there is a flush of green, fresh as April; and perhaps we find a few of the grand water-flags still in flower, for they often bloom late, and seem like gold and purple banners hanging out over some ancient keep, whose colours are mirrored in the moat below. There also the beautiful arrow-head, with its snow-white flowers and arrow-pointed leaves, may be found, looking like ivy growing about the water. Many a rare plant, too little known, flourishes beside and in our sedge-fringed meres and bright meadow streams, where the overhanging trees throw cooling shadows over their grassy margins, and the burning noon of summer never penetrates. Such pleasant places are always cool, for there the grass never withers, nor are the paths ever wholly dry; and when we come upon them unaware, after having quitted the heat and glare of the brown dusty highway, it seems like travelling into another country, whose season is spring. And there the water-plantain spreads its branches, and throws out its pretty broad leaves and rose-tinted flowers, which spread up to the very border of the brook, and run in among the pink-flowers of the knot-grass, which every ripple sets in motion. Further on, the purple loosestrife shews its gorgeous spikes of flowers, seeming like a border woven by the moist fingers of the Naiads, to curtain their crystal baths; while the water-violets appear as if growing to the roofs of their caves, the foliage clinging to the vaulted-silver, and only the dark-blue flowers shewing their heads above the water. There, too, is the bog-pimpernel, almost as pretty as its scarlet sister, which may still be found in bloom by the wayside, though its flowers are not so large. Beautiful it looks, a very flower in arms, nursed by the yielding moss, on which it leans, as if its slender stem and prettily-formed leaves were too delicate to rest on common earth so had a soft pillow provided for its exquisite flowers to repose upon. Nor does it change, when properly dried, if transferred to the herbarium, but there looks as fresh and beautiful as it did while growing the very fairy of flowers. Nor will the splendid silver-weed be overlooked, with its prettily-notched leaves, which underneath have a rich silvery appearance; while the golden-coloured flowers, which spread out every way, are soft as velvet to the feel. Then the water has its grass like the field, and is sometimes covered with great meadows of green, among which are seen flowers as beautiful as grow on the inland pastures. The common duck-weed covers miles of water with its little oval-shaped leaves, and will from one tiny root soon send out buds enough to cover a large pool, for every shoot it sends forth becomes flower and seed while forming part of the original stem, and these are reproduced by myriads, and would soon cover even the broad Atlantic, were the water favourable to its growth, for only the land could prevent it from multiplying further. Row a boat through this green landlooking-like meadow, and almost by the time you have reached the opposite shore-though you have sundered millions of leaves, and made a glassy course wide enough for a carriage to pass through the water, not a trace will be left, where all was bright and clear as a broad silver mirror, but all again be covered with green, as with a smooth carpet. Beside its velvet-meadows, the water has its tall forests and spreading underwood, and stateliest amongst its trees are the flower-bearing rushes, one of which is the very Lady of the Lake, crowned with a red tiara of blossoms. The sword-leaved bur-weed, and many another aquatic plant, are like bramble, fern, and shrub, the underwood of the tall sedge, which the nodding bulrushes overtop. Nor is forest or field frequented with more beautiful birds or insects than those found among our water-plants. Then we have the beautiful white water-lily, which seems to bring an old world before us, for it belongs to the same species which the Egyptians held sacred, and the Indians worshipped. To them it must have seemed strange, in the dim twilight of early years, when nature was so little under-stood, to see a flower disappear at night, leaving on the surface no trace of where it bloomed-to re-appear again in all its beauty, as it still does, on the following morning. And lovely it looks, floating double lily and shadow, with its rounded leaves, looking like green resting places for this Queen of the Waters to sit upon, while dipping at pleasure her ivory sandals in the yielding silver; or, when rocked by a gentle breeze we have fancied they looked like a moving fairy-fleet on the water, with low green hulls, and white sails, slowly making for the shore. The curious little bladder-wort is another plant that immerses itself until the time for flowering arrives, when it empties all its water-cells, fills them with air, and rises to the surface. It may now be seen almost everywhere among water-plants. In a few more weeks it will disappear, eject the air, fill its little bladders once more with water, and, sinking down, ripen its seed in its watery bed, where it will lie until another summer warns and wakens it to life, when it will once more empty its water-barrels, fill them with air, and rising to the light and sunshine, again beautify the surface with its flowers. Sometimes water-insects open the valves of these tiny bladders, and get inside; but they cannot get out again until the cells are once more unlocked to receive air. Many another rare and curious plant may be found by the water-side in August, where sometimes the meadow-sweet still throws out a few late heads of creamy-coloured bloom, that scent the air with a fragrance delicious as May throws out, when all her hawthorns are in blossom, for though June is a season Half-prinked with spring, with summer half-embrowned,' August is a month richly flushed with the last touches of summer, toned down here and there with the faint grays of autumn, before the latter has taken up his palette of kindled colours. Still, we cannot look around, and miss so many favourite flowers, which met our eye on every side a few weeks ago, without noticing many other changes. The sun sinks earlier in the evening; mists rise here and there and dim the clear blue of twilight; we see wider rents through the foliage of the trees and hedges, and, above all, we miss the voices of those sweet singers, whose pretty throats seemed never at rest, but from morning to night shook their speckled feathers with swellings of music. Yet how almost imperceptibly the days draw in, like the hands of a large clock, that appear motionless, yet move on with true measured footsteps to the march beaten by Time. So do the days come out and go in, and move through the land of light and darkness, to the shelving steep, down which undated centuries have shot and been forgotten. Soon those pleasant meadows that are still so green, and where the bleating of white flocks, and the lowing of brindled herds, are yet heard, will be silent, the hedges naked, and not even the hum of an insect sound in the air. Where the nearly ripe harvest, when the breeze blows, now murmurs like the sea in its sleep, and where the merry voices of sun-tanned reapers will soon be heard, the trampled stubble only will be seen, and brown bare patches of miry earth, where the straw has blackened and rotted, shew like the coverings of newly-made graves. Even now unseen hands are tearing down the tapestry of flowers which summer had hung up to shelter her orchestra of birds in the hedges. What few flowers the woodbine again throws out-children of its old age-have none of the bloom and beauty about them like those born in the lusty sunshine of early summer. For even she is getting gray, and the white down of thistles, dandelion, groundsel, and many other hoary seeds streak her sun-browned hair. There are blotches of russet upon the ferns that before only unfolded great fans of green, and in the sunset the fields of lavender seem all on fire, as if the purple heads of the flowers had been kindled by the golden blaze which fires the western sky. Fainter, and further between each note, the shrill chithering of the grasshopper may still be heard; and as we endeavour to obtain a sight of him, the voice fades away beyond the beautiful cluster of red-coloured pheasant's-eye, which country maidens still call rose-a-ruby, believing that if they have not a sweetheart before it goes out of flower, they will have to wait for another year until it blooms again. The dwarf convolvulus twines around the corn, and the bear-bine coils about the hedges, the former winding round in the direction of the sun, and the latter twining in a contrary direction. Sometimes, where the little pink convolvulus has bound several stems of corn together, and formed such a tasteful wreath as a young lady would be proud to wear on her bonnet, the nest of the pretty harvest-mouse may be found. This is the smallest quadruped known to exist -the very humming-bird of mammalia-for when full-grown it will scarcely weigh down a worn farthing, while the tiny nest, often containing as many as eight or nine young ones, may be shut up easily within the palm of the hand, though so compactly made, that if rolled along the floor like a ball, not a single fibre of which it is formed will be displaced. How the little mother manages to suckle so large a family within a much less compass than a common cricket-ball, is still a puzzle to our greatest naturalists. It is well worth hiding your-self for half an hour among the standing-corn, just for the pleasure of seeing it run up stalks of wheat to its nest, which it does much easier than we could climb a wide and easy staircase, for its weight does not even shake a grain out of the ripened ears that surmount its pretty chamber. It may be kept in a little cage, like a white mouse, and fed upon corn; water it laps like a dog; and it will turn a wheel as well as any squirrel. Often it amuses itself by coiling its tail around anything it can get at, and hanging with its mite of a body downward, will swing to and fro for many minutes together. One, while thus swinging, would time its motions to the ticking of the clock that stood in the apartment, and fall asleep while suspended. There are now thousands of lady-birds about, affording endless amusement to children; only a few years ago, they invaded our southern coast in such clouds, that the piers had to be swept, and millions of them perished in the sea; many vessels crossing over from France had their decks covered with them. That pretty blue butterfly, which looks like a winged harebell, is now seen everywhere; and as it balances itself beside some late cluster of purple sweet-peas, it is difficult to tell which is the insect and which the flower, until it springs up and darts off with a jerk along its zigzag way. On some of the trees we now see a new crop of leaves quite as fresh and beautiful as ever made green the boughs in vernal May, and a pleasant appearance they have beside the early-changing foliage that soonest falls, looking in some places as if spring, summer, and autumn had combined their varied foliage together. And never does the country look more beautiful than now, if the eye can at once take in a wide range of scenery from some steep hillside. Patches of green, where the cattle are feeding on the second crop of grass, are all one emerald - looking in the distance as if April had come again, and tinted them with the softest flush of spring; and if you are near enough, you may still hear the milk-maid's carol morning and night, for that green eddish causes the cows to yield as much milk as they did when feeding knee-deep amid the flowers of May. Then great fields of ripe corn rush in like floods of sunshine between these green spaces, widening and yellowing out on every hand, shewing here and there a thin dark band, which would hardly arrest the eye, were it not beaded with trees that shoot up from amid these low hedgerows. And in the remote distance, where the same dark lines run between the cornfields, they look like streaks of grass on a yellow clay land in spring-a fallow, sun-lighted land, where beside these thin lines no green thing grows. The roofs of the little cottages are all that is seen to float amid this golden ocean of corn, which appears to have washed over wall, window, and door, and left but the sloping thatch on the face of that great yellow sea of waving and rolling ears. That old roadside alehouse, which we thought so picturesque while eating our bread and cheese in the sunny porch an hour ago, is, excepting the roof and the tall sign-post, lost in the long perspective of sweeping acres of cornfields; and the winding road we passed, which leads to it, seems to have been filled up by the long eary ranks that, from here, appear to have closed since we came by. We no longer hear the creaking of the old sign, though the gust that just now swept by and sent a white wave over the corn, must have made the old Green Dragon sigh again as it swung before the door. Soon that great bay-window, which looks so pleasantly over the long range of corn-lands, will be filled with thirsty reapers in the evening, and well-to-do farmers in the daytime, as they ride down to see how the work of harvest progresses, while great bottles and wooden flagons will be passing all day long, out full, and in empty, at that old porch, until all the corn is garnered. Children, who come with their parents, because they have no other home, until harvest is over, will be hanging about that great long trough before the door, filling bottles with water for the reapers, and throwing it over one another, and wetting the hay that stands ever ready in those movable racks for any mounted horseman who chooses to give his nag a bite as well as a sup, when he pulls up at that well-known halting-place. Right proud is mine host of his great kitchen, with its clean sanded floor, and white long settles, that will seat a score or more of customers. You may see your face in the brass copper and block-tin cooking utensils that hang around, for often during the hay and corn harvest, the great farmers call and dine or lunch there, whose homes lie a long way from those open miles of cornfields. It would make a hungry man's mouth water to see what juicy hams and fine streaky flitches ever hang up on the oaken beams which span the ceiling of that vast kitchen. As to poultry-finer chickens were never eaten than those we saw picking about the horse-trough, nor do plumper ducks swim than those we sent quacking into the green pond-covered with duck-weed-when our ragged terrier barked at them as we left the porch. In some places, if it has been what the country-people call a forward summer, harvest has already commenced, though it is more general about the beginning of next month, which heralds in autumn. And now the fruit is ripe on the great orchard-trees, the plums are ready to drop through very mellowness, and there is a rich redness on the sunny-side of the pears, and on many of the apples. What strangely-shaped trees are still standing in many of our old English orchards, some of them so aged, that all record of when they were first planted was lost a century or two ago! Apple-trees soold that their arms have to be supported on crutches, as the decayed trunk would not bear the branches when they are weighed down with fruit, for some of these codlins are as big as a baby's head. Many of these hoary trees are covered with misletoe, or wrapped about with great flakes of silver moss, causing them in the distance to look like bearded Druids, while some of the trunks are bent and humped with knots, and stoop until they are almost double under the weight of fruit and years. And when does pear ever taste so sweet or plum so rich and mellow, as those which have fallen through very ripeness, and are picked up from the clean green after-math under the orchard-trees, as soon as they have fallen?-few that are gathered can ever be compared with these. A hot day in August, a parching thirst, and a dozen golden-drop plums, picked up fresh from the cool grass, is a thing to be remembered, and talked about after, like Justice Shallow's pippins, in Shakspeare. They must not be shaken down by the wind, but slip off the boughs through sheer ripeness, and leave the stalks behind, so rich are they then that they would even melt in the crevice of an iceberg. But we have now reached the borders of a fruitful land, where the corn is ready for the sickle, and the wild fruits hang free for all; for though the time of summer's departure has arrived, she has left plenty behind for all, neither forgetting beast nor bird in her bounty. And now the voices of the labourers who are coming up to the great gathering, may be heard through the length and breadth of the land, for the harvest-cry has sounded. HISTORICALIn the old Roman calendar, August bore the name of Sextilis, as the sixth month of the series, and consisted but of twenty-nine days. Julius Caesar, in reforming the calendar of his nation, extended it to thirty days. When, not long after, Augustus conferred on it his own name, he took a day from February, and added it to August, which has consequently ever since consisted of thirty-one days. This great ruler was born in September, and it might have been expected that he would take that month under his patronage; but a number of lucky things had happened to him in August, which, moreover, stood next to the month of his illustrious predecessor, Julius; so he preferred Sextilis as the month which should be honoured by bearing his name, and August it has ever since been among all nations deriving their civilisation from the Romans. CHARACTERISTICS OF AUGUSTIn height of mean temperature, August comes only second, and scarcely second, to July; it has been stated, for London, as 61.6° . The sun, which enters the constellation Virgo on the 23rd, is, on the 1st of the month, above the horizon at London for 15 hours 22 minutes; on the last, for 13 hours 34 minutes: at Edinburgh, for 16 hours 40 minutes, and 14 hours 20 minutes, on these days respectively. |