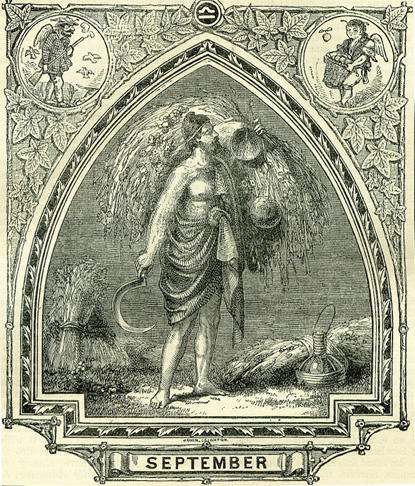

September Next him September marched eke on foot, Yet was he hoary, laden with the spoil Of harvest riches, which he made his boot, And him enriched with bounty of the soil; In his one hand, as fit for harvest's toil, He held a knife-hook; and in th' other hand A pair of weights, with which he did assoil Both more and less, where it in doubt did stand, And equal gave to each as justice duly scanned. DESCRIPTIVEFar inland within sight of our wave-was shores, along the margins of our pleasant rivers, in level meadows and sinking valleys, on gentle uplands and sloping hill-sides, there is now a busy movement, for men and maidens are out, with their beaded sickles, to gather in the golden harvest. The village streets are comparatively silent. Scores of cottages are shut up-one old woman perhaps only left to look after the whole row-for even the children have gone to glean, and many of the village artizans find it pleasant to quit their usual employment for a few days, and go out to reap the corn. There will be no getting a coat mended or a shoe cobbled for days to come. If there is a stir of life in the village street, those who move along are either coming from or going to the reapers, bringing back empty bottles and baskets, or carrying them filled with ale and provisions. A delicate Cockney, who can only eat the lean of his overdone mutton-chop, with the aid of pickles, would stand aghast at the great cold dinner spread out for the farmer and his house-servants-men, each with the appetite of three, and maidens who can eat meat that is all fat. Pounds of fat beef, bacon, and ham, great wedges of cheese, cold apple-pies, with crusts two inches thick, huge brown loaves, lumps of butter, and a continually gurgling ale, are the viands which a well-to-do farmer places before his servants, and shares with them, for he argues, he cannot expect to get the proper quantity of work out of them unless they live well. To get his harvest in quick, while the weather is fine, is the study of the great corn-grower; and such a far-seeing man scarcely gives the cost a consideration, for he knows that those who delay will, if the weather changes, be ready to pay almost any price for reapers; so he gets in his corn ' while the sun shines.' If well got in, what a price it will fetch in the market, compared with that which was left out in the rain, until it became discoloured and sprouted! And as he points to his ricks with pride, he asks what's the value of the extra bullock, the pig or two, and the few barrels of ale the reapers consumed, compared to such a crop as that; and he is right. It is an anxious time for the farmer. He is continually looking at his weather-glass, and watching those out-of-door signs which denote a change in the weather, and which none are better acquainted with than those who pass so much of their life in the fields. Unlike the manufacturer, who carries on his business indoors what-ever the changes of the season may be, the farmer is dependent on the weather for the safety of his crop, and can never say what that will be, no matter how beautiful it may look while standing, until it is safely garnered. Somehow he seems to live nearer to God than the busy indwellers of cities, for he puts his trust in Him who has promised that He will always send 'seed-time and harvest.' How gracefully a good reaper handles his sickle, and clutches the corn-one sweep, and the whole armful is down, and laid so neat and level, that when the band is put round the sheaf, the bottom of almost every straw touches the ground when it is reared up, and the ears look as level as they did while growing! It is a nice art to make those corn-bands well, which bind the sheaves-to twist the ears of corn so that they shall all cluster together without shaking out the grain, and then to tie up the sheaves, so round and plump, that they may be rolled over, when stacking or loading, without hardly a head becoming loose. There are rich morsels of colour about the cornfield where the reapers are at work. The handkerchiefs which they bind around their foreheads, to keep off the sun-the white of their shirt-sleeves, making spots of light amid the yellow corn-the gleaners in costumes of every hue, blue, red, and gray, stooping or standing here and there, near the overhanging trees in the hedgerows-make such a diversity of colour as please the eye, while the great blue heaven spans over all, and a few loose silver clouds float gently over the scene. In such a light, the white horses seem cut out of silver, the chestnuts of ruddy gold, while the black horses stand out against the sky, as if cut in black marble. What great gaps half a-dozen reapers soon make in the standing corn! Half-an-hour ago, where the eye dwelt on a broad furrow of upstanding ears, there is now a low road of stubble, where trails of the ground-convolvulus may be seen, and the cyanus of every hue, which the country children call corn-flowers. Pretty is it, too, to see the little children gleaning, each with a rough bag or pocket before it, and a pair of old scissors dangling by its side, to cut off the straw, for only the ears are to be placed in the gleaner's little bag. Then there is the large poke, under the hedge, into which their mother empties the tiny glean-bags, and that by night will be filled, and a heavy load it is for the poor woman to carry home on her head, for a mile or two, while the little ones trot along by her side, the largest perhaps carrying a small sheaf, which she has gleaned, and from which the straw has not been cut, while the ears hang down and mingle with her flowing hair. A good, kind-hearted farmer will, like Boaz of old, when he spoke kindly to pretty Ruth, let his poor neighbours glean ' even amongst the sheaves.' The dry hard stubble, amid which they glean, cuts the bare legs and naked arms of the poor children like wires, making them as rough at times as fresh-plucked geese. Rare gleaning there is where the 'stooks' have stood, when the wagons come to 'lead' the corn out of the field. The men stick the sheaves on their forks as fast as you can count them, throw them into the wagon, then move on to the next 'stook'-each of which consists of eight or ten sheaves-then there is a rush and scramble to the spot that is just cleared, for there the great ears of loose and fallen corn lie thick and close together, and that is the richest gleaning harvest yields. Who has not paused to see the high-piled wagons come rocking over the furrowed fields, and sweeping through the green lanes, at the leading-home of harvest? All the village turns out to see the last load carried into the rick-yard; the toothless old grandmother, in spectacles, stands at her cottage-door; the poor old labourer, who has been long ailing, and who will never more help to reap the harvest, leans on his stick in the sun-shine; while the feeble huzzas of the children mingle with the deep-chested cheers of the men, and the silvery ring of maiden-voices-all welcoming home the last load with cheery voices, especially where the farmer is respected, and has allowed his poor neighbours to glean. Some are mounted on the sheaves, and one sheaf is often decorated with flowers and ribbons, the last that was in the field; and sometime a pretty girl sits sideways on one of the great fat horses, her straw-hat ornamented with flowers and ears of corn. Right proud she is when hailed by the rustics as the Harvest Queen! Then there are the farmer, his wife, and daughters, all standing and smiling at the open gate of the stack-yard; and proud is the driver as he cocks his hat aside, and giving the horses a slight touch, sends the last load with a sweep into the yard, that almost makes you feel afraid it will topple over, so much does it rock coming in at this grand finish. Rare gleaning is there, too, for the birds, and many a little animal, in the long lanes through which the wagons have passed during the harvest, for almost every overhanging branch has taken toll from the loads, while the hawthorn-hedges have swept over them like rakes. The longtailed field-mouse will carry off many an ear to add to his winter-store, and stow away in his snug nest under the embankment. What grand subjects, mellowed by the setting suns of departed centuries, do these harvest-fields bring before a picture-loving eye! Abraham among his reapers-Isaac musing in the fields at even-tide-Jacob labouring to win Rachel -Joseph and the great granaries of Egypt-Ruth "Standing in tears among the alien corn" and the harvests of Palestine, amid which our Saviour walked by the side of His disciples. All these scenes pass before a meditative mind while gazing over the harvest-field, filled with busy reapers and gleaners, and we think how, thousands of years ago, the same picture was seen by the patriarchs, and that Ruth herself may have led David by the hand, while yet a child, through the very fields in which she herself had gleaned. But the frames in which these old pictures were placed were not carved into such beautiful park-like scenery and green pastoral spots as we see in England, for there the harvest-fields were hemmed in by rocky hills, and engirded with deserts, where few trees waved, and the villages lay far and wide apart. And, instead of the sound of the thrasher's flail, oxen went treading their weary round to trample out the corn, which in spring shot up in green circles where they had trodden. Winged seeds now ride upon the air, like insects, many of them balanced like balloons, the broad top uppermost, and armed with hooked grapnels, which take fast hold of whatever they alight upon. We see the net-work of the spider suspended from leaf to branch, which in the early morning is hung with rounded crystals, for such seem the glittering dew-drops as they catch the light of the rising sun. The hawthorn-berries begin to shew red in the hedges, and we see scarlet heps where, a few weeks ago, the clustering wild-roses bloomed. Here and there, in sunny places, the bramble-berries have began to blacken, though many yet wear a crude red, while some are green, nor is it unusual, in a mild September, to see a few of the satin-like bramble blossoms, putting out here and there, amid a profusion of berries. The bee seems to move wearily from flower to flower, for they lie wider asunder now than they did a month ago, and the little hillocks covered with wild-thyme, which he scarcely deigned to notice then, he now gladly alights upon, and revels amid the tiny sprigs of lavender-coloured bloom. The spotted wood-leopard moth may still be seen, and the goat-moth, whose larva is called the oak-piercer, and sometimes the splendid tiger-moth comes sailing by on Tyrian wings, that fairly dazzle the eye with their beauty. But at no season of the year are the sunsets so beautiful as now; and many who have travelled far say, that nowhere in the world do the clouds hang in such gaudy colours of ruby and gold, about the western sky, as they do in England during autumn, and that these rich effects are produced through our being surrounded by the sea. Nor is sunrise less beautiful seen from the summit of some hill, while the valleys are still covered with a white mist. The tops of the trees seem at first to rise above a country that is flooded, while the church-spire appears like some sea-mark, heaving out of the mist. Then comes a great wedge-like beam of gold, cutting deep down into the hollows, skewing the stems of the trees, and the roofs of cottages, gilding barn and outhouse, making a golden road through a land of white mist, which seems to rise on either hand, like the sea which Moses divided for the people of Israel to pass through dryshod. The dew-drops on the sun-lighted summit the feet rest upon are coloured like precious stones of every dye, and every blade of grass is beaded with these gorgeous gems. Sometimes the autumnal mists do not rise more than four or five feet above the earth, revealing only the heads of horse and rider, who seem to move up as if breasting a river, while the shepherd and milkmaid shew like floating busts. The following word-painting was made in the early sunrise, while we were wanderers, many long years ago: On the far sky leans the old ruined mill; Through its rent sails the broken sunbeams glow; Gilding the trees that belt the lower hill, And the old oaks which on its summit grow; Only the reedy marsh that sleeps below, With its dwarf bushes is concealed from view; And now a straggling thorn its head doth shew, Another half shakes off the misty blue Just where the smoky gold streams through the heavy dew. And there the hidden river lingering dreams, You scarce can see the banks that round it lie; That withered trunk, a tree, or shepherd seems, Just as the light or fancy strikes the eye. Even the very sheep which graze hard by, So blend their fleeces with the misty haze, They look like clouds shook from the cold gray sky Ere morning o'er the unsunned hill did blaze- The vision fades as they move further off to graze. We have often fancied that deer never look so beautiful, as when in autumn they move about, or couch amid the rich russet-coloured fern-when there is a blue atmosphere in the distance, and the trees scattered around are of many changing hues. There is a majesty in the movements of these graceful animals, both in the manner of their walk, and the way they carry their heads, crowned with picturesque antlers. Then they are so particular in their choice of pasture, refusing to eat where the verdure is rank or trampled down, also feeding very slowly, and when satisfied, lying down to chew the cud at their ease. Their eyes are also very beautiful, having a sparkling softness about them like the eyes of a woman, while the senses of sight, smelling, and hearing are more perfect than that of the generality of quadrupeds. Watch their attitude while listening! that raised head, and those erect ears, catch sounds so distant that they would not be within our own hearing, were we half a mile nearer the sound from the spot where the herd is feeding. Beautiful are the fern and heath covered wastes in September-with their bushes bearing wild-fruits, sloe, and bullace, and crab; and where one may lie hidden for hours, watching how beast, bird, and insect pass their time away, and what they do in these solitudes. In such spots, we have seen great gorse-bushes in bloom, high as the head of a mounted horseman; impenetrable places where the bramble and the sloe had become entangled with the furze and the branches of stunted hawthorns, that had never been able to grow clear of the wild waste of underwood-spots where the boldest humter is compelled to draw in his rein, and leave the hounds to work their way through the tangled maze. Many of these hawthorns were old and gray, and looked as if some giant hand had twisted a dozen iron stems into one, and left them to grow and harden together in ridges, and knots, and coils, that looked like the relics of some older world-peopled with other creations than those the eye now dwells upon. Some few such spots we yet know in England, of which no record can be found that they were ever cultivated. And over these bowery hollows, and this dense underwood, giant oaks threw their arms so far out, that we marvelled how the hoary trunks, which were often hollow, could bear such weights without other support than the bole from which they sprang-spewing a strength which the builder man, with all his devices, is unable to imitate. Others there were-gnarled, hoary trunks -which, undated centuries ago, the bolt had blackened, and the lightning burned, so monstrous that they took several men, joined hand-to-hand, to girth them, yet still they sent out a few green leaves from their branchless tops, like aged ruins whose summits the ivy often covers. And in these haunts the red fox sheltered, and the gray badger had its home, and there the wild-cat might some-times be seen glaring like a tiger, through the branches, on the invader of its solitude. It seemed like a spot in which vegetation had struggled for the mastery for ages, and where the tall trees having overtopped the assailing underwood, were hemmed in every way, and besieged until they perished from the rank growth below. But every here and there were sunny spots, and open glades, where the turf rose elastic from the tread, and great green walls of hazel shot up more like trees than shrubs. There were no such nuts to he found anywhere as on these aged hazels, which, when ripe, we could shake out of their husks, or cups-nothing to be found in our planted. Nutteries so firm and sweet as those grown in this wildwood, and Nutting Day is still kept up as a rural holiday in September in many parts of England, in the neighbourhood of merry greenwoods. Towards the end of the month, old and young, maidens and their sweethearts, generally accompanied by a troop of happy boys and girls, sally out with bags and crooks, bottles and baskets, containing drink and food, pipes and tobacco for the old people, and all that is required for a rough rustic repast 'all under the greenwood tree.' One great feature of this old rural merry-making, is their going out in their very homeliest attire, and many there were who had worn the same nutting dress for years. Old Royster's leather-shorts had been the heirloom of two generations, and when last we heard of them, were still able to bid defiance to brake or brier. A fashionable picnic is shorn of all that heart-happiness which is enjoyed by homely country-people, for, in the former, people are afraid of appearing natural. Pretty country girls were not called ' young ladies' at these rural holidays, but by their sweet-sounding Christian names; and oh what music there is in 'Mary' compared with 'Miss!' What merry laughter have we heard ringing through those old woods, as some pretty maiden was uplifted by her sweet-heart to reach the ripe cluster of nuts which hung on the topmost bough, where they had been browned by the sun, when, overbalancing himself, they came down among the soft wood-grass, to the great merriment of every beholder! Some were sure to get lost, and there was such shouting and hallooing as awakened every echo, and sent the white owls sailing half asleep in search of some quieter nook, where they could finish their nap in peace. Then what a beautiful banquet-hall they find in some open sunny spot, surrounded with hazels, and overtopped by tall trees, where the golden rays, shining through the leaves, throw a warm mellow light on all around! Nothing throws out smoother or more beautifully coloured branches than the hazel, the bark of which shines as if it had been polished. And who has not admired its graceful catkins in spring, that droop and wave like elegant laburnums, and are seen long before its leaves appear? Nor does autunm, amid all its rich coloured foliage, skew a more beautiful object than a golden hued hazel-copse, which remains in leaf later than many of the trees. When this clear yellow tint of the leaves is seen, the nuts are ripe, and never before-one shake at a branch, and down they come rattling out of their cups by scores-real 'brown sheelers,' as they are called by country, people. Wood-nuts gathered at the end of September or the beginning of October, have the true 'nutty' flavour, which is never tasted if they are gathered before. These wild-nuts are seldom found hollow '-so they are called when the kernel is eaten by the white grub, the egg of which was laid while the nut was in a soft state early in summer. And unless this grub has eaten its way out, and left visible the hole by which it escaped, we have never yet been able to discover what part of the shell the fly pierced when depositing its egg. This grub is still a puzzle, nor do we remember to have ever seen its re-appearance as a perfect weevil in spring, though we have often looked on while letting itself down from the nut by the thread it had spun after escaping from the shell. How long it remains in the earth is not at present known; nor is there a certainty that the grub buries itself in the earth at all while in a state of pupa, though it must find something to feed on somewhere before reaching a state of imago, some imagine, unless it obtain nourishment enough in the kernel it had eaten, prior to undergoing this later change. This, we believe, is a nut which none of our many clever naturalists have yet cracked to their own satisfaction. HISTORICALWhen the year began in March, this was the seventh of its months; consequently, was properly termed September. By the commencement of the year two months earlier, the name is now become inappropriate, as is likewise the case with its three followers-October, November, and December. When Julius Caesar reformed the calendar, he gave this month a 31st day, which Augustus subsequently took from it; and so it has since remained. Our Saxon ancestors called it Gerst monat, or barley-month, because they then realized this crop; one of unusual importance to them, on account of the favourite beverage which they brewed from it. On the 23rd, the sun enters the constellation Libra, and passes to the southward of the equator, thus producing the autumnal equinox; a period usually followed by a course of stormy weather. September, however, is often with us a month of steady and pleasant weather, notwithstanding that in the mornings and evenings the first chills of winter begin to be felt. On the 1st of the month, at London, the sun is up 12h 28m, and on the 30th, 11h 38m. |