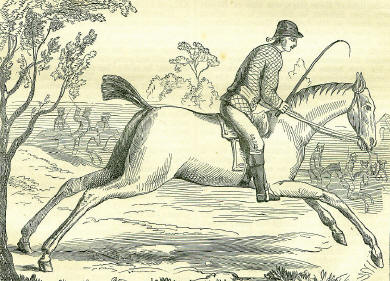

29th AprilBorn: King Edward IV of England, 1441 (?) Rouen; Nicolas Vansittart, Lord Bexley, English statesman, 1766. Died: John Cleveland, poet, 1659, St. Michael's, College Hill; Michael Ruyter, Dutch admiral, 1676, Syracuse; Abbe Charles de St. Pierre, philanthropist, 1743, Paris. Feast Day: St. Fiachna of Ireland, 7th century; St. Hugh, abbot of Cluni, 1109; St. Robert, abbot of Molesme, 1110; St. Peter, martyr, 1252. A BRACE OF CAVALIER POETSJohn Cleveland, the noted loyalist poet during the reign of Charles the First and the Common-wealth, was a tutor and fellow of St. John's College, Cambridge. His first appearance in political strife was the determined opposition he organized and maintained against the return of Oliver Cromwell, then a comparatively obscure candidate in the Puritan interest, as member of Parliament for Cambridge. Cromwell's stronger genius prevailing, he gained the election by one vote; upon which Cleveland, with the combined foresight of poet and prophet, exclaimed that a single vote had ruined the church and government of England. On the breaking out of the civil war, Cleveland joined the king at Oxford, and greatly contributed to raise the spirits of the cavaliers by his satires on the opposite party. After the ruin of the royal cause, he led a precarious fugitive life for several years, till, in 1655, he was arrested, as 'one of great abilities, averse, and dangerous to the Commonwealth.' Cleveland then wrote a petition to the Protector, in which, though he adroitly employed the most effective arguments to obtain his release, he did not abate one jot of his principles as a royalist. He appeals to Cromwell's magnanimity as a conquerer, saying: Methinks, I hear your former achievements interceding with. you not to sully your glories with trampling on the prostrate, nor clog the wheel of your chariot with so degenerous a triumph. The most renowned heroes have ever with such tenderness cherished their captives, that their swords did but cut out work for their courtesies. He thus continues: I cannot conceit that my fidelity to my prince should taint me in your opinion; I should rather expect it would recommend me to your favour.' This idea was paraphrased in Hudibras: The ancient heroes were iliustr'ous For being benign, and not blust'rous Against a vanquished foe: their swords Were sharp and trenchant, not their words, And did in fight but cut work out T' employ their courtesies about. My Lord, you see my crimes; as to my defence, you bear it about you. I shall plead nothing in my justification but your Highness' clemency, which, as it is the constant inmate of a valiant breast, if you be graciously pleased to extend it to your suppliant, in taking me out of withering durance, your Highness will find that mercy will establish you more than power, though all the days of your life were as pregnant with victories as your twice auspicious third of September.' The transaction was highly honourable to both. parties. Cromwell at once granted full liberty to the spirited petitioner; though, personally, he had much to forgive, as is clearly evinced by Cleveland's DEFINITION OF A PROTECTOR What's a Protector? He's a stately thing, That apes it in the nonage of a king; A tragic actor-Cesar in a clown, He's a brass farthing stamped with a crown; A bladder blown, with other breaths puffed full; Not the Perillus, but Perillus' bull: AEsop's proud ass veiled in the lion's skin; An outward saint lined with a devil within: An echo whence the royal sound doth come, But just as barrel-head sounds like a drum; Fantastic image of the royal head, The brewer's with the king's arms quartered; He is a counterfeited piece that shows Charles his effigies with a copper nose; In fine, he's one we must Protector call- From whom, the King of kings protect us all. After his release, Cleveland went to London, where he found a generous patron, and ended his days in peace; though he did not live to be rejoiced (or disappointed) by the Restoration. Cleveland's poetry, at one time highly extolled, now completely sunk in oblivion, has shared the common fate of all works composed to support and flatter temporary opinions and prejudices. Contemporary with Milton, Cleveland was considered immeasurably superior to the author of Paradise Lost. Even Philips, Milton's nephew, asserts that Cleveland was esteemed the best of English poets. Milton's sublime work could scarcely struggle into print, while edition after edition of Cleveland's coarse satires were passing through the press; now, when Cleveland is for-gotten, we need say nothing of the estimation in which Milton is held. In connexion with the life of Cleveland, it may be well to notice a brother cavalier poet, Richard Lovelace, who in April 1642, was imprisoned by the parliament in the Gatehouse, for presenting a petition from the county of Kent, requesting them to restore the king to his rights. It was looked upon as an act of malignancy, or anti-patriotic loyalism, as we might now explain it. There is something fascinating in the gay, cavalier, self-devoted, poet nature, and tragic end of Lovelace. It was while in prison that he wrote his beautiful lyric, so heroic as to his sufferings, so charmingly sweet to his love, so delightful above all for its assertion of the independence of the moral on the physical and external conditions: When love with unconfined wings Hovers within my gates, And my divine Althea brings To whisper at my grates; When I lye tangled in her haire, And fettered with her eye, The birds that wanton in the aire Know no such libertie. When flowing cups ran swiftly round With no allaying Thames, Our carelesse heads with roses crowned, Our hearts with loyal flames; When thirsty grief e in wine we steepe, When healths and draughts goe free, Fishes, that tipple in the deepe, Know no such libertie. When, linnet-like, confined I With shriller note shall sing The mercye, sweetness, majestye, And glories of my kung; When I shall voyce aloud how good He is, how great should be, Th' enlarged winds, that curl the flood, Know no such libertie. Stone walls do not a prison make, Nor iron barres a cage, Mindes innocent and quiet take That for an hermitage: If I have freedom in my love, And in my soule am free, Angels alone, that soare above, Enjoy such libertie. Lovelace, according to Anthony Wood, was 'the most amiable and beautiful person that eye ever beheld.' He had a gentleman's fortune, which he spent in the royal cause, and in succouring royalists more unfortunate than himself. Perhaps there was a dash of thoughtlessness and extravagance about him also-for we must remember he was a poet. The end was, that Lovelace, the high-spirited cavalier, poet, and lover, died in obscurity and poverty in a lodging in Shoe Lane, Fleet Street-memorable in the history of another poet, Chatterton-and was buried notelessly at the end of Bride's Church. RUYTERFrom the condition of a common sailor arose the singular man who, in the seventeenth century, made the little half-ruined country of Holland the greatest maritime power in Europe. In 1672, while Louis XIV overran that state, it triumphed over him by Ruyter's means at sea, just as Nelson checked the Emperor Napoleon in the midst of his most glorious campaigns. In the ensuing year, he met the combined fleets of France and England in three terrible battles, and won from D'Estrees, the French commander, the generous declaration that for such glory as Ruyter acquired he would gladly give his life. In a minor expedition against the French. in Sicily, the noble Dutch commander was struck by a cannon-ball, which deprived him of life, at the age of sixty-nine. COWPER THORNHILL'S RIDEApril 29, 1745, Mr. Cowper Thornhill, keeper of the Bell Inn at Stilton, in Huntingdonshire, performed a ride which was considered the greatest ever done in a day up to that time. A contemporary print, here copied, presents the following statement on the subject: 'He set out from his house at Stilton at four in the morning, came to the Queen's Arms against Shoreditch Church in three hours and fifty-two minutes; returned to Stilton again in four hours and twelve minutes; came back to London again in four hours and thirteen minutes, for a wager of five hundred guineas. He was allowed fifteen hours to perform it in, which is 213 miles, and he did it in twelve hours and seventeen minutes. It is reckoned the greatest performance of the kind ever yet known. Several thousand pounds were laid upon the affair, and the roads for many miles were lined with people to see him pass and repass.'  Mr. Cowper Thornhill is spoken of in the Memoirs of a Banking-house, by Sir William Forbes (Edin. 1860), as a man carrying on a large business as a corn-factor, and as 'much respected for his gentlemanly manners, and generally brought to table by his guests.' Stow records a remarkable feat in riding as performed on the 17th July 1621, by Bernard Calvert of Andover. Leaving Shoreditch in London that morning at three o'clock, he rode to Dover, visited Calais in a barge, returned to Dover and thence back to St. George's church in Shoreditch, which he reached at eight in the evening of the same day. Dover being seventy-one miles from London, the riding part of this journey was, of course, 142 miles. A ride remarkable for what it accomplished in the daylight of three days, was that of Robert Cary, from London to Edinburgh, to inform King James of the death of Queen Elizabeth. Cary, after a sleepless night, set out on horse-back from Whitehall between nine and ten o'clock of Thursday forenoon. That night he reached Doncaster, 155 miles. Next day he got to his own house at Witherington, where he attended to various matters of business. On the Saturday, setting out early, he would have reached Edinburgh by mid-day, had he not been thrown and kicked by his horse. As it was, he knelt by King James's bed-side at Holyrood, and saluted him King of England, soon after the King had retired to rest; being a ride of fully 400 miles in three days. The first rise of Wolsey from an humble station was effected by a quick ride. Being chaplain to Henry VII (about 1507), he was recommended by the Bishop of Winchester to go about a piece of business to the Emperor Maximilian, then at a town in the Low Countries. Wolsey left London at four one afternoon by a boat for Gravesend, there took post-horses, and arrived at Dover next morning. The boat for Calais was ready to sail. He entered it, reached Calais in three hours; took horses again, and was with the Emperor that night. Next morning, the business being dispatched, he rode back without delay to Calais, where he found the boat once more on the eve of starting. He reached Dover at ten next day, and rode to Richmond, which he reached in the evening, having been little more than two days on the journey.-Cavendish's Life of Wolsey. |