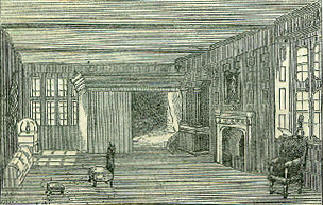

28th AprilBorn: Charles Cotton, poet, 1630, Ovingden; Anthony, seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, philanthropist, statesman, 1801. Died: Thomas Betterton, actor, 1710, London; Count Struensee, executed, 1772, Copenhagen; Baron Dentin, artist, learned traveller, 1825, Paris; Sir Charles Bell, anatomist and surgeon, 1842, Hallow Park, near Worcester; Sir Edward Codrington, naval commander, 1851, London; Gilbert A. à Becket, comic prose writer, 1856. Feast Day: St Vitalis, martyr, about 62; Saints Didymus and Theodore, martyrs, 304; St. Pollio and others, martyrs in Pannonia, 304; St. Patricius, bishop of Pruse, in Bithynia, martyr; St. Cronan, abbot of Roscrea, Ireland, about 640. CHARLES COTTONHigh on the roll of England's minor poets must be placed the well-known name of 'Charles Cotton, of Beresford in the Peak, Esquire.' He was descended from an honourable Hampshire family; his father, also named Charles, was a man of parts and accomplishments, and in his youth a friend and fellow-student of Mr. Hyde, subsequently Lord Chancellor Clarendon. The elder Cotton, marrying an heiress of the Beresford family in Derbyshire, settled on an estate of that name near the Peak, and on the romantic banks of the river Dove. The younger, Charles, studied at Cambridge, from whence he returned to his father's house, and, seemingly not being intended for any profession, passed the early part of his life in poetical studies, and the society of the principal literary men of the day. In 1656, being then in his twenty-sixth year, he married a distant relative of his own, the daughter of Sir Thomas Hutchinson; and this marriage appears from the husband's verses to have been a very happy one. He soon after succeeded to the paternal acres, but found them almost inundated with debt; mainly the consequence, it appears, of the imprudent living in which his father had long indulged. The poet was often a fugitive from his creditors: a cave is shown in Dovedale which proved a Patmos to him in some of his direst extremities. It was not till after the Restoration that he began to publish the productions of his muse. There is a class of his writings very coarse and profane, which were extremely popular in their day, but from which we gladly avert our eyes, in order to feast on his serious and sentimental effusions, and contemplate him as a votary of the most gentle of sports, that of the angle. Coleridge says, 'There are not a few of his poems replete with every excellence of thought, image, and passion, which we expect or desire in the poetry of the minor muse.' The long friendship and unfeigned esteem of such a man as Izaak Walton is a strong evidence of Cotton's moral worth. An ardent angler from youth, being brought up on the banks of one of the finest trout streams in England, we need not be surprised to find Cotton intimately acquainted with his contemporary brother-angler, author, and poet, Izaak Walton. How the acquaintance commenced is easier to be imagined than discovered now; but it is certain that they were united in the strictest ties of friendship, and that Walton frequently visited Beresford Hall, where Cotton had erected a fishing house, on a stone in the front of which was inscribed their incorporated initials, with the motto, Sacrum Piscatoribus. A pleasant primitive practice then prevailed of adepts in various arts adopting their most promising disciples as sons in their special pursuits. Thus Ben Jonson had a round dozen of poetical sons; Elias Ashmole was the alchemical son of one Backhouse, thereby inheriting his adopted father's most recondite secrets; and Cotton became the angling son of his friend Walton. But though. Walton was master of his art in the slow-running, soil-coloured, weed-fringed rivers of the south, there was much that Cotton could teach his angling parent with respect to fly-fishing in the rapid sparkling streams of the north country. So, when the venerable Walton was preparing the fifth edition of his Compleat Angler, he solicited his son Cotton to write a second part, containing Instructions how to Angle for a Trout or Grayling in, a Clear Stream; and this second part, published in 1676, has ever since formed one book with the first. As is well known, Cotton's addition is written, like the first part, in the form of a dialogue, and though it may, in some respects, be inferior to its forerunner, yet in others it probably possesses more interest, from its description of wild romantic scenery, and its representation of Cotton himself, as a well-bred country gentleman of his day: courteous, urbane, and hospitable, a scholar without a shadow of pedantry; in short, a cavalier of the old school, as superior to the fox-hunting squire of the eighteenth century as can readily be conceived. As there are now no traces of Walton on his favourite fishing-river, the Lea, Dovedale has become the Mecca of the angler, as well as a place of pilgrimage for all lovers of pure English literature, honest simplicity of mind, unaffected piety, and the beautiful in nature.  It is more than thirty years ago since the writer made his first visit to Dovedale, and easily identified every point in the scenery as described by Cotton. Beresford Hall was then a farm-house; the semi-sacred Walton chamber a store-room for the produce of the soil; and the world-renowned fishing-house in a sorrowful state of dilapidation. The estate has since then been purchased by Viscount Beresford, who, by a very slight expenditure of money, with exercise of good taste, has restored everything as nearly as possible to the same state as when Cotton lived. Mr. Anderdon, the most enthusiastic of Walton's admirers, who seems to have caught the good old angler's best style of composition, thus describes the Walton chamber as it now is. The scene is Beresford Hall, the time during Cotton's life, who is supposed to be from home. The Angler and Painter are travellers, guided by the host of the inn at the neighbouring village of Alstonefields. The servant is showing the Hall. Cotton's attached wife died about 1670, and he some time after married the Countess Dowager of Ardglass, who had a jointure of fifteen hundred pounds per annum. This second marriage relieved his more pressing necessities; but at his death, which took place in 1687, the administration of his estate was granted to his creditors, his wife and children renouncing their claims. IMPIOUS CLUBSAn order in council appeared, April 28, 1721, denouncing certain scandalous societies which were believed to hold meetings for the purpose of ridiculing religion. A bill was soon after brought forward in the House of Peers for the suppression of blasphemy, which, however, was not allowed to pass, some of the lords professing to dread it as an introduction to persecution. It appears that this was a time of extraordinary profligacy, very much in consequence of the large windfalls which some had acquired in stock-jobbing and extravagant speculation. Men had waxed fat, and were come to be unmindful of their position on earth, as the creatures of a superior power. They were unbounded in indulgence, and an outrageous disposition to mock at all solemn things followed. Hence arose at this time fraternities of free-living gentlemen, popularly recognised then, and remembered since, as Hell-fire clubs. Centering in London, they had affiliated branches at Edinburgh and at Dublin, among which the metropolitan secretary and other functionaries would occasionally perambulate, in order to impart to them, as far as wanting, the proper spirit. Grisly nicknames, as Pluto, the Old Dragon, the King of Tartarus, Lady Envy, Lady Gomorrah (for there were female members too), prevailed among them. Their toasts were blasphemous beyond modern belief. It seemed an ambition with these misguided persons how they should most express their contempt for everything which ordinary men held sacred. Sulphurous flames and fumes were raised at their meetings to give them a literal resemblance to the infernal regions. Quiet, sober-living people heard of the proceedings of the Hell-fire clubs with the utmost horror, and it is not wonderful that strange stories came into circulation regarding them. It was said that now and then a distinguished member would die immediately after drinking an unusually horrible toast. Such an occurrence might well take place, not necessarily from any supernatural intervention, but from the moral strain required for the act, and possibly the sudden revulsion of spirits under the pain of remorse. In Ireland, before the days of Father Mathew, there used to be a favourite beverage termed scaltheen, made by brewing whisky and butter together. Few could concoct it properly, for if the whisky and butter were burned too much or too little, the compound had a harsh or burnt taste, very disagreeable, and totally different from the soft, creamy flavour required. Such being the case, a good scaltheen-maker was a man of considerable repute and request in the district he inhabited. Early in the present century there lived in a northern Irish town a very respectable tradesman, noted for his abilities in making scaltheen. He had learned the art in his youth, he used to say, from an old man, who had learned it in his youth from another old man, who had been scaltheen-maker in ordinary to what we may here term, for propriety's sake, the H. F. club in Dublin. With the art thus handed down, there came many traditional stories of the H. F.'s, which the writer has heard from the noted scaltheen-maker's lips. How, for instance, they drank burning scaltheen, standing in impious bravado before blazing fires, till, the marrow melting in their wicked bones, they fell down dead upon the floor. How there was an unaccountable, but unmistakeable smell of brim-stone at their wakes; and how the very horses evinced a reluctance to draw the hearses containing their wretched bodies to the grave. Strange stories, too, are related of a certain large black cat belonging to the club. It was always served first at dinner, and a word lightly spoken of it was considered a deadly insult, only to be washed out by the blood of the offender. This cat, however, as the story goes, led to the ultimate dissolution of the club, in a rather singular manner. As a rule, from their gross personal insults to clergymen, no member of the sacred profession would enter the club-room. But a country curate, happening to be in Dublin, boldly declared that if the H. F.'s asked him to dinner, he would consider it his duty to go. Being taken at his word, he was invited, and went accordingly. In spite of a torrent of execrations, he said grace, and on seeing the cat served first, asked the president the reason of such an unusual proceeding. The carver drily replied that he had been taught to respect age, and he believed the cat to be the oldest individual in company. The curate said he believed so, too, for it was not a eat but an imp of darkness. For this insult, the club determined to put the clergyman to instant death, but, by earnest entreaty, allowed him five minutes to read one prayer, apparently to the great disgust of the cat, who expressed his indignation by yelling and growling in a terrificmanner. Instead of a prayer, however, the wily curate read an exorcism, which caused the cat to assume its proper form of a fiend, and fly off, carrying the roof of the club-house with it. The terrified members then, listening to the clergy-man's exhortations, dissolved the club, and the king, hearing of the affair, rewarded the curate with a 0 bishopric. Other stories equally absurd, but not quite so fit for publication, are still circulated in Ireland. It is said that in the H. F. clubs blasphemous burlesques of the most sacred events were frequently performed; and there is a very general tradition, that a person was accidentally killed by a lance during a mocking representation of the crucifixion. A distinguished Irish antiuary has very ingeniously attempted to account la these stories, by supposing that traditionary accounts of the ancient mysteries, miracle plays, and ecclesiastical shows, once popular in Ireland, have been mixed up with traditions of the H. F. clubs; the religious character of the former having been forgotten, and their traditions merged into the alleged profane orgies of the latter. But, more probably, the recitals in question are merely imaginations arising from the extreme sensation which the H. F. system excited in the popular mind. CAPTAIN MOLLOYOn the 28th of April 1795, a naval court-martial, which had created considerable excitement, and lasted for sixteen days, came to a conclusion. The officer tried was Captain Anthony James Pye Molloy, of His Majesty's ship Caesar; and the charge brought against him was, that he did not bring his ship into action, and exert himself to the utmost of his power, in the memorable battle of the 1st of June 1794. The charge in effect was the disgraceful one of cowardice; yet Molloy had frequently proved himself to be a brave sailor. The court decided that the charge had been made good; but, 'having found that on many previous occasions Captain Molloy's courage had been unimpeachable,' he was simply sentenced to be dismissed his ship, instead of the severe penalty of death. A very curious story is told to account for this example of the 'tears of the brave.' It is said that Molloy had behaved dishonourably to a young lady to whom he was betrothed. The friends of the lady wished to bring an action of breach of promise against the inconstant captain, but she declined doing so, saying that God would punish him. Some time afterwards, they accidentally met in a public room at Bath. She steadily confronted him, while he, drawing back, mumbled some incoherent apology. The lady said, 'Captain Molloy, you are a bad man. I wish you the greatest curse that can befall a British officer. When the day of battle comes, may your false heart fail you!' His subsequent conduct and irremediable disgrace formed the fulfilment of her wish. A TRAVELED GOATOn the 28th April 1772, there died at Mile End a goat that had twice circumnavigated the globe; first, in the discovery ship Dolphin, under Captain Wallis; and secondly, in the renowned Endeavour, under Captain Cook. The lords of the Admiralty had, just previous to her death, signed a warrant, admitting her to the privileges of an in-pensioner of Greenwich Hospital, a boon she did not live to enjoy. On her neck she had for some time worn a silver collar, on which was engraved the following distich, composed by Dr. Johnson. Perpetui ambita his terra praemia lactis, Hac habet, altrici capra secunda Jovis. |